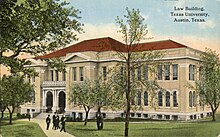

University of Texas School of Law

| The University of Texas School of Law | |

|---|---|

| Parent school | University of Texas at Austin |

| Established | 1883 |

| School type | Public law school |

| Endowment | $215.5 million (2018)[1][2] |

| Dean | Bobby Chesney[3] |

| Location | Austin, Texas, United States 30°17′19″N 97°43′51″W / 30.288666°N 97.730762°W |

| Enrollment | 985 (2023)[4] |

| Faculty | 311 (2023)[4] |

| USNWR ranking | 16th (tied) (2024)[5] |

| Bar pass rate | 94.01% (2023)[6] |

| Website | law |

The University of Texas School of Law (Texas Law) is the law school of the University of Texas at Austin, a public research university in Austin, Texas. According to Texas Law’s ABA disclosures, 87.20% of the Class of 2022 obtained full-time, long-term bar passage required employment (i.e. as attorneys) nine months after graduation.[7]

In 2017, the school had 19,000 living alumni.[8] Amongst its alumni are former U.S. Supreme Court Justice and U.S. Attorney General Tom C. Clark; former U.S. Secretary of State James A. Baker; former U.S. Secretary of Treasury Lloyd Bentsen; former White House Senior Advisor Paul Begala; former Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives Sam Rayburn; former litigator Sarah Weddington who represented Jane Roe in the landmark case Roe v Wade; and Wallace B. Jefferson, the first African American Chief Justice of the Texas Supreme Court.

History

[edit]The University of Texas School of Law was founded in 1883.[8] Prior to the Civil Rights Movement, the school was limited to white students, but the school's admissions policies were challenged from two different directions in high-profile 20th century federal court cases that were important to the long struggle over segregation, integration, and diversity in American education.

Sweatt v. Painter (1950)

[edit]

The school was sued in the civil rights case of Sweatt v. Painter (1950). The case involved Heman Marion Sweatt, a black man who was refused admission to the school on the grounds that substantially equivalent facilities (meeting the requirements of Plessy v. Ferguson) were offered by the state's law school for blacks. When the plaintiff first applied to the University of Texas, there was no law school in Texas which admitted blacks. Instead of granting the plaintiff a writ of mandamus, the Texas trial court "continued" the case for six months to allow the state time to create a law school for blacks, which it developed in Houston.

The Supreme Court reversed the lower court decision, saying that the separate school failed to offer Sweatt an equal legal education. The court noted that the University of Texas School of Law had 16 full-time and three part-time professors, 850 students and a law library of 65,000 volumes, while the separate school the state set up for blacks had five full-time professors, 23 students and a library of 16,500 volumes. But the court held that even "more important" than these quantitative differences were differences such as "reputation of the faculty, experience of the administration, position and influence of the alumni, standing in the community, traditions and prestige". Because the separate school could not provide an "equal" education, the court ordered that Hemann Sweatt be admitted to University of Texas School of Law.

Sweatt v. Painter was the first major test case in the long-term litigation strategy of Thurgood Marshall and the NAACP Legal Defense Fund that led to the landmark Supreme Court decision in the case of Brown v. Board of Education in 1954.[9] Marshall and the NAACP correctly calculated that they could dismantle segregation by building up a series of precedents, beginning at Texas Law, before moving on to the more explosive question of racial integration in elementary schools.

Hopwood v. Texas (1996)

[edit]In 1992, plaintiff Cheryl Hopwood, a White American woman, sued the school on the grounds that she had not been admitted even though her grades and test scores were better than those of some minority candidates who were admitted pursuant to an affirmative action program. Texas Monthly editor Paul Burka later described Hopwood as "the perfect plaintiff to question the fairness of reverse discrimination" because of her academic credentials and personal hardships which she had endured (including a young daughter suffering from a muscular disease).[10]

With her attorney Steven Wayne Smith, later a two-year member of the Texas Supreme Court, Hopwood won her case, Hopwood v. Texas, in the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, which ruled that the school "may not use race as a factor in deciding which applicants to admit in order to achieve a diverse student body, to combat the perceived effects of a hostile environment at the law school, to alleviate the law school's poor reputation in the minority community, or to eliminate any present effects of past discrimination by actors other than the law school".[11] The case did not reach the Supreme Court.

However, the Supreme Court ruled in Grutter v. Bollinger (2003), a case involving the University of Michigan, that the United States Constitution "does not prohibit the law school's narrowly tailored use of race in admissions decisions to further a compelling interest in obtaining the educational benefits that flow from a diverse student body". This effectively reversed the decision of Hopwood v. Texas.[12]

Admissions

[edit]Texas Law is among the more selective law schools in the nation. For the class of 2019, 5,803 students applied and 1,017 (17.53%) were accepted. Of accepted students, 280 (27.53%) enrolled. The enrolled class of 2021 has a class median LSAT score of 169. The median GPA for the enrolled class is 3.80.[13] Women make up 57% of the class, and 32% of the class identify as minority students. The average age of the class was 24. Texas Law enrolled students from 25 US states for the class of 2019, with out-of state students comprising 32% of the class.[14] Emphasizing its role as a public institution, Texas Law is required by the state legislature to reserve 65% of the seats in each first-year class for Texas residents.[15]

Rankings

[edit]Historically, Texas Law has been ranked the top law school in the state and the 15th best school in the nation by the legal news website Above the Law.[16] The U.S. News & World Report rankings, the most widely used and influential ranking of American law schools, ranked Texas Law as tied for the 16th best law school in the nation in 2020.[16] Additionally, Above the Law, which uses an outcome-focused ranking system, ranked Texas the 12th best law school in the U.S. in 2019.[17] In 2020, USNWR also ranked Texas as the 15th best law school in the U.S. for a student's return on investment.[18]

Publications

[edit]Students at the University of Texas School of Law publish thirteen law journals:[19]

- American Journal of Criminal Law

- Texas Environmental Law Journal

- Texas Hispanic Journal of Law and Policy

- Texas Intellectual Property Law Journal

- Texas International Law Journal

- Texas Journal of Oil, Gas & Energy Law

- Texas Journal of Women and the Law

- Texas Journal on Civil Liberties & Civil Rights

- Texas Law Review

- Texas Review of Entertainment and Sports Law

- Texas Review of Law and Politics

- The Journal of Law and Technology at Texas

- The Review of Litigation

Bernard and Audre Rapoport Center for Human Rights and Justice

[edit]The Bernard and Audre Rapoport Center for Human Rights and Justice serves as a focal point for critical, interdisciplinary analysis and practice of human rights and social justice.[20][21] The Rapoport Center was founded in 2004 by Professor Karen Engle, Minerva House Drysdale Regents Chair in Law, thanks to a donation from the Bernard and Audre Rapoport Foundation to the University of Texas School of Law.[22][23] The Rapoport Foundation was founded in 1986 by Bernard Rapoport and his wife Audre. In 2010, Daniel Brinks, Associate Professor of Government at the University of Texas at Austin, became co-director of the Center.[24] The Center has over one hundred affiliated faculty members from various schools and departments within the University of Texas at Austin.

In February 2013, the Rapoport Center received a three-year, $150,000 grant from the Creekmore and Adele Fath Charitable Foundation to highlight the life and career of Sissy Farenthold, an American Democratic politician, activist, lawyer and educator, perhaps best known for her run for Texas Governor and for her nomination for Vice President in the 1972 Democratic National Convention.[25] The project documents Farenthold's contributions to Texas and U.S. politics, the women's peace movement, and international human rights and justice. The Rapoport Center will work with the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History (where Farenthold's papers are housed) in order to process and preserve Farenthold's papers, digitize archival documents and images, produce videotaped interviews, and expand the content of the Rapoport Center's website.[26]

Center for Women in Law

[edit]In 2008 the law school announced the creation of the Center for Women in Law,[27] "To eliminate the barriers that have thwarted the advancement of women in the legal profession for the past several decades, and thereby enhance the legal profession and its ability to serve an increasingly diverse and globally connected society."[28]

Continuing Legal Education

[edit]The University of Texas School of Law Continuing Legal Education is one of the oldest and most distinguished providers of professional education in the country, offering over 50 advanced conferences annually that provide CLE and CPE credit to national legal and accounting professionals. Some of the School's signature programs include Stanley M. Johanson Estate Planning Workshop, Taxation Conference, Jay L. Westbrook Bankruptcy Law, Ernest E. Smith Oil, Gas and Mineral Law, Immigration and Nationality Law and Page Keeton Civil Litigation, which have been offered continuously for over 35 years. Other highly regarded programs in the portfolio include Mergers and Acquisitions Institute, International Upstream Energy Transactions, Parker C. Fielder Oil and Gas Tax (presented with the IRS) and Patent Law Institutes presented in Austin and at the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

U.S. Supreme Court clerkships

[edit]Since 2005, Texas has had four alumni serve as judicial clerks at the United States Supreme Court. This record gives Texas a ranking in the top 20 among all law schools for supplying such law clerks for the period 2005-2017. Texas has placed 35 clerks at the U.S. Supreme Court in its history, ranked 13th among law schools; this group includes Diane Wood (class of 1975) who clerked for Justice Harry Blackmun during the 1976 Term, and is now the Chief Judge of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit.

Tarlton Law Library

[edit]The Tarlton Law Library is one of the largest academic law libraries in the country, with a physical collection of more than a million volumes and extensive electronic resources. In addition to a comprehensive collection of United States primary and secondary legal materials in print and digital formats, Tarlton has a broad interdisciplinary collection from the social sciences and humanities. Special collections at Tarlton include significant foreign and international law resources; the papers of former United States Supreme Court Justice Tom Clark; feature films and fiction related to law and popular culture; and the Gavel Archive, a collection of feature films, TV shows, and fiction related to law and popular culture, all candidates for and winners of the American Bar Association’s prestigious Silver Gavel Award. Tarlton is a depository for United States, European Union, and Canadian government documents. Its extensive collection of rare and antiquarian law books includes noted collections of early legal dictionaries, Texas law, and the works of John Selden.

Employment

[edit]Texas has maintained strong employment outcomes for its graduates relative to other law schools.[29] According to UT official 2018 ABA-required disclosures, 85.0% of the Class of 2018 had obtained full-time, long-term, J.D.-required employment (i.e. as attorneys) nine months after graduation.[30] 92.8% of the class obtained employment in careers that preferred or required a J.D.[30] UT's Law School Transparency under-employment score is 7.2%, indicating the percentage of the Class of 2018 unemployed, pursuing an additional degree, or working in a non-professional, short-term, or part-time job nine months after graduation.[31]

Costs

[edit]The total cost of attendance (indicating the cost of tuition, fees, and living expenses) at Texas Law for the 2016–2017 academic year is $56,161 for residents and $73,831 for non-residents.[32] The Law School Transparency estimated debt-financed cost of attendance for three years is $197,389 for residents and $254,278 for nonresidents.[33]

Notable people

[edit]Alumni

[edit]Faculty

[edit]Current faculty

[edit]- Philip Bobbitt – Previously the A.W. Walker Centennial Chair at the University of Texas

- Robert M. Chesney – Dean & Honorable James A. Baker III Chair in the Rule of Law and World Affairs, co-founder of Lawfare blog

- Dick DeGuerin – Adjunct professor teaching criminal law

- Karen Engle - Minerva House Drysdale Regents Chair in Law and the Founder and Co-director of the Bernard and Audre Rapoport Center for Human Rights and Justice

- Ward Farnsworth – W. Page Keeton Chair in Tort Law

- Bryan A. Garner – Visiting associate professor and director of the short-lived Texas/Oxford Center for Legal Lexicography

- Douglas Laycock – Robert E. Scott Distinguished Professor

- Sanford Levinson – W. St. John Garwood and W. St. John Garwood, Jr. Centennial Chair

- Basil Markesinis – Jamail Regents Professor in Law

- Lawrence G. Sager – Former dean of University of Texas School of Law and the Alice Jane Drysdale Sheffield Regents Chair

- Stephen Vladeck – Charles Alan Wright Chair In Federal Courts

- Abraham Wickelgren - Fred and Emily Marshall Wulff Centennial Chair in Law

Former faculty

[edit]- Jack Balkin – Knight Professor of Constitutional Law and the First Amendment at Yale Law School

- Mitchell Berman – Professor of Law at the University of Pennsylvania Law School

- Ted Cruz – U.S. Senator and former Presidential Candidate; adjunct professor of Constitutional Law

- Julius Getman – Professor and activist in Labor and Employment law

- Lino Graglia – Dalton Cross Professor of Law at the University of Texas School of Law

- Leon A. Green – American legal realist and dean of Northwestern University School of Law (1929–1947)

- W. Page Keeton – Attorney and dean of the University of Texas School of Law for a quarter century

- Brian Leiter – Karl N. Llewellyn Professor of Jurisprudence at the University of Chicago Law School

- William Powers, Jr. – Former dean of University of Texas School of Law and former President of the University of Texas at Austin

- Elizabeth Warren – U.S. Senator and presidential candidate

- Charles Alan Wright – American constitutional lawyer and coauthor of the 54-volume treatise, Federal Practice and Procedure

- Mark Yudof – Long-serving faculty member who later became president of the University of California System, chancellor of the University of Texas System, and president of the University of Minnesota

References

[edit]- ^ "Financial Information". University of Texas Law School Foundation. Retrieved August 13, 2019.

- ^ Maxwell Locke & Ritter, LLC (January 14, 2019). 2018 Audited Financials by UT Law School Fdn. University of Texas Law School Foundation. Retrieved August 13, 2019.

- ^ "Dean and Leadership". Texas Law. University of Texas School of Law. Retrieved August 13, 2019 – via law.utexas.edu.

- ^ a b "ABA 509 2023". University of Texas Standard 509 Information Report. UT Law. Retrieved September 17, 2024.

- ^ "University of Texas–Austin". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved April 10, 2024.

- ^ "First Time Bar Passage Calendar Year 2023" (XLSX). American Bar Association. April 11, 2024. Retrieved August 22, 2024.

- ^ "Texas at Austin, University of Employment Summary 2022 Graduates". abarequireddisclosures.org. American Bar Association. Retrieved April 7, 2024.

- ^ a b "History of the Law School". The University of Texas School of Law. Retrieved August 3, 2017.

- ^ Julius L. Chambers, "A Tribute to Justice Thurgood Marshall," Stanford Law Review, Vol. 44, Summer, 1992, p. 1249

- ^ Burka, Paul. "Law – Cheryl Hopwood." Texas Monthly (Sept. 1996)

- ^ Hopwood v. Texas, 78 F.3d 932 (5th Cir. 1996)

- ^ See Grutter v. Bollinger, 539 U.S. 306 (2003) (stating that the Supreme Court's purpose in deciding Grutter's case was "to resolve the disagreement among the Courts of Appeals on a question of national importance: Whether diversity is a compelling interest that can justify the narrowly tailored use of race in selecting applicants for admission to public universities. Compare Hopwood v. Texas, 78 F.3d 932 (CA5 1996) (holding that diversity is not a compelling state interest) with [another case] holding that it is.")

- ^ "Standard 509 Disclosure".

- ^ "Quick Facts".

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions | What is the deal with the 65% Texas residency requirement?". utexas.edu. University of Texas. Retrieved April 8, 2024.

- ^ a b Rubino, Kathryn (April 30, 2019). "What Are The Best Law Schools, Historically Speaking?". Above the Law. Retrieved March 2, 2020.

- ^ "The ATL 2019 Top Law School Rankings". Above the Law. Retrieved March 2, 2020.

- ^ "10 Law Schools Where You can Pay Off Your Debt". usnwr.com. Retrieved March 2, 2020.

- ^ "Student Organizations and Journals". The University of Texas School of Law. Retrieved February 26, 2015.

- ^ "Rapoport Center for Human Rights and Justice - What We Do". Utexas.edu. Retrieved August 3, 2017.

- ^ "The Bernard & Audre Rapoport Foundation". The Bernard & Audre Rapoport Foundation. Retrieved June 12, 2019.

- ^ "Minerva House Drysdale Regents Chair". Endowments.giving.utexas.edu. June 17, 1983. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- ^ "Bernard & Audre Rapoport Foundation". Archived from the original on March 5, 2012. Retrieved September 26, 2013.

- ^ "Rapoport Center for Human Rights and Justice - Staff". Utexas.edu. Retrieved August 3, 2017.

- ^ "A Guide to the Frances Tarlton Farenthold Papers, 1913-2014". Lib.utexas.edu. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- ^ "Texas NOW Blog: Meet Sissy Farenthold". Texas NOW Blog. Archived from the original on January 10, 2019 – via www.nowtexas.org.

- ^ Smith, Diana (Winter 2008). "The Center for Women in Law" (PDF). UT Law: 8–9. Retrieved February 26, 2015.

- ^ "Center for Women in Law – The Austin Manifesto". Utexas.edu. May 1, 2009. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- ^ "Texas Report". www.lstreports.com. Retrieved June 12, 2019.

- ^ a b "ABA Required Disclosures".

- ^ "University of Texas at Austin Profile".

- ^ "Tuition and Expenses".

- ^ "University of Texas at Austin Profile".