Uruma

Uruma

うるま市 | |

|---|---|

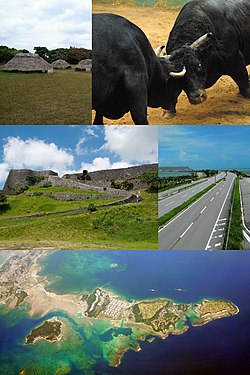

Uruma City Montage | |

Location of Uruma in Okinawa Prefecture | |

| Coordinates: 26°22′45″N 127°51′27″E / 26.37917°N 127.85750°E | |

| Country | Japan |

| Region | Kyushu |

| Prefecture | Okinawa Prefecture |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Toshio Shimabukuro |

| Area | |

| • Total | 86.00 km2 (33.20 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 204 m (669 ft) |

| Population (May 1, 2013) | |

| • Total | 118,330 |

| • Density | 1,400/km2 (3,600/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+9 (Japan Standard Time) |

| – Tree | Ryuūkyū kuroki |

| – Flower | Santanka |

| – Bird | Chaan (Ryukyuan cock) |

| Phone number | 098-974-3111 |

| Address | 1-1-1 Midori-machi, Uruma-shi, Okinawa-ken 904–2292 |

| Website | www |

Uruma (うるま市, Uruma-shi) is a city located in Okinawa Prefecture, Japan.[2] The modern city of Uruma was established on April 1, 2005, when the cities of Gushikawa and Ishikawa were merged with the towns of Katsuren and Yonashiro (both from Nakagami District).[2][3] As of May 1, 2013, the city has an estimated population of 118,330 and a population density of 1,400 people per km2. The total area is 86.00 km2. The city covers part of the east coast of the south of Okinawa Island, the Katsuren Peninsula, and the eight Yokatsu Islands.[4] The Yokatsu Islands include numerous sites important to the Ryukyuan religion, and the city as a whole has numerous historical sites, including: Katsuren Castle, Agena Castle, and Iha Castle and the Iha Shell Mound.[2][3] It is home to the largest venue for Okinawan bullfighting. The Mid-Sea Road, which crosses the ocean and connects the Yokatsu Islands to the main island of Okinawa, is now a symbol of Uruma.[2][3][5]

Uruma is noted for its role in hosting large-scale refugee camps and the initial organization of local government of Okinawa immediately after the Battle of Okinawa in 1945. As such the city is considered the home of the starting point of the restoration of civil life in Okinawa immediately after the end of World War II.[6][7] United States maintains four military bases in Uruma, some of which span other municipalities in Okinawa: Kadena Ammunition Storage Area, Camp McTureous, Camp Courtney, and White Beach Naval Facility. The bases cover 12.97% of the total area of the city. Two controversies have surrounded American military bases in Uruma: the 1959 Okinawa F-100 crash which killed and injured numerous students and residents, and the transport of Agent Orange via the White Beach Naval Facility for testing in Okinawa in the early 1960s as part of the classified Project AGILE.[8][9][10]

Etymology

In the Japanese language the name of the city is written using the hiragana syllabary instead of kanji characters because, according to the city, it looks endearing and soft.[11] The name of the city of Uruma comes from a poetic name for Okinawa Island. A folk etymology, which was adopted by the city itself,[12] segments uruma into uru (fine sand or coral in Okinawan) and *ma (island?). Another theory relates it to urumaa, meaning cricket in Okinawan.

The Okinawan origin of the word, however, has long been questioned. In fact, it was in mainland Japan that the word was first attested and eventually came to refer to Okinawa. The first known reference to uruma is a waka poem by Fujiwara no Kintō in the early 11th century. He compared a woman's coldheartedness to the incomprehensible speech of drifters from Ureung Island (迂陵島, identified as Ulleung Island) of Goryeo Kingdom, which Kintō called Silla, a practice rather common in Heian-period Japan. However, the association with Ulleung Island was soon forgotten because the reference to Silla was dropped when his poem was recorded in the Senzai Wakashū (1188). Thereafter waka poets only thought uruma as an island somewhere outside Japan with an unintelligible language. At the same time, it evoked a sense of familiarity because the phrase uruma no ichi (market in Uruma) was poetically associated with Mino Province. From the viewpoint of mainland Japanese poets, Okinawa might have been an ideal referent of uruma because, despite the exotic name of Ryūkyū, the first reference to Okinawan-composed waka poems was as early as 1496. The first known identification of uruma as Okinawa Island can be found in the Moshiogusa (1513), but the association remained weak for some time. For example, Hokkaido, in addition to Okinawa, was referred to as uruma in the Shōzaishū (1597). The mainland Japanese poetic practice was adopted by Okinawan waka poets in the late 17th century. The Omoidegusa (1700), a purely Japanese poetic diary by Shikina Seimei, is known for its extensive use of the word uruma.[13]

History

Early history

In the Sanzan Period (1322–1429), or Three Kingdom period, numerous gusuku, or castles were built across Okinawa Island. The area of present-day Uruma fell under the control of the Chūzan Kingdom, which covered the central area of Okinawa Island and its nearby islands. The Katsuren area of Uruma became notably prosperous in the mid-15th century. Katsuren Castle, and a surrounding jōkamachi castle town, were constructed in this period.

Under the Ryukyu Kingdom six magiri, a type of regional administrative district in pre-modern Okinawa, covered areas of present-day Uruma: 'Nzatō Magiri (parts of which were also located in present-day Okinawa City), Gushichaa Magiri, Kachin magiri, and Yunagushiku Magiri. Nakagushiku Magiri included Tsuken Island.[14][15]

The Ryūkyū Kingdom ended in 1872 with the establishment of the Ryūkyū Domain, which was soon abolished with the establishment of Okinawa Prefecture in 1879. The existing system of magiri in Uruma continued with the establishment of Okinawa Prefecture. The magiri were abolished in 1907 under Imperial Edict 46, and the central government extended the establishment of cities, towns, and village organization to Okinawa Prefecture. In 1908 the area of present-day Uruma was reorganized as the five villages of Misato, Gushikawa, Katsuren, and Yonashiro.[14][15]

In the pre-war period Uruma had the most productive sugarcane industry in Okinawa Prefecture due to sources of irrigation and fertile soil.

The areas of present-day Uruma were affected in World War II during the initial part of the Battle of Okinawa. L-Day, the initial land invasion of Okinawa Island, occurred on April 1, 1945. American forces swept across the island quickly, and by April 5 had secured the entirety of the Katsuren Peninsula. A smaller invasion force captured Tsuken Island on the same day, and encountered stiff resistance from the Japanese military. Tsuken Island was completely devastated by fire in the battle. After the capture of Tsuken, American forces reached Ikei Island on April 9, thus securing all the Yokatsu Islands.[16] The area that became Ishikawa was a major refugee camp set up by the American military near the end of the battle.

Post-war period

The Okinawa Advisory Council, the predecessor to the United States Military Government of the Ryukyu Islands was established in Ishikawa, and temporarily became the political, educational, and cultural center of Okinawa. In 1946 the Advisory Council was moved to the village of Sashiki, now a district of Nanjō, refugees began a large-scale movement to return to their homes, and the population of Ishikawa decreased rapidly. In the aftermath of World War II the Ishikawa area of Uruma was used as a large-scale refugee camp. The camp was built and operated by the U.S. occupation forces, and is considered the starting point of the reconstruction and recovery of Okinawa after the war.[6][7]

The 1959 Okinawa F-100 crash occurred on June 30, 1959. In the crash, a United States Air Force North American F-100 Super Sabre on a flight from nearby Kadena Air Base suffered an engine fire and crashed into Miyamori Elementary School and surrounding houses. Eleven students and six other people in the neighborhood were killed, and 210 were injured, including 156 students at the school. The F-100 crash contributed to ill will among the Okinawan population towards the U.S. occupation authorities, and strengthened calls for the island to be returned to the control of the Japanese government.[17][18]

The city of Uruma was formed on April 1, 2005 from the merger of the cities of Gushikawa and Ishikawa, and the towns of Katsuren and Yonashiro, both from Nakagami District.

Economy

Uruma, despite its low amount of arable land, is noted for several agricultural products. The city, like most areas of Okinawa, produces sugarcane. Cut flowers, notably chrysanthemums, are a relatively new agricultural product. Land improvement has made small-scale rice production possible. Pigs have been raised in Uruma since the end of World War II.

Uruma produces also several specialty agricultural products. The city is noted for the production of mozuku seaweed. Tsuken Island produces a specialty variety of carrots, which are known in Japan as the "Tsuken Ninjin". "Nuchi-masu", or the "salt of life", is produced from the mineral-rich seawater of Uruma. Yamashiro-cha is a locally produced tea grown in the Yamashiro area of the city.[6][19]

Geography

Uruma is located near the center of Okinawa Island, facing east. The city occupies the southern rim of Kin Bay as well as the north of Nakagusuku Bay.[2] The highest point in the city is Mount Ishikawa at 204 metres (669 ft).[1][20]

Rivers

The longest river in the city is the Tengan River, which runs for 12.20 kilometres (7.58 mi) from Mount Yomitan (201 metres (659 ft)) to Kin Bay in the Akano district of the city.[21]

Neighboring municipalities

Land areas

The city consists of three geographic areas: a land area on Okinawa Island proper, the Katsuren Peninsula, and the eight Yokatsu Islands. The majority of the city of Uruma sits on a dissected plateau, and has numerous hills and indentations. The islands of the city are flat and low-lying and are primarily composed of Ryukyuan limestone.[3]

Okinawan mainland

The land area of the city of Uruma on Okinawa Island includes the former cities of Ishikawa to the north and Gushikawa to the south. These areas are the most populated parts of the city, and are crossed by the Okinawa Expressway and Ishikawa By-pass. The area of Uruma on the Okinawan mainland is bordered by Kin Bay to the east, and has a long coastline with significant industrial development. The northernmost point of the city is marked by Ishikawadake (204 metres (669 ft)), a low hill on the border of Uruma and the city of Kin. The Kinbu Fishing Port is located in the Gushikawa area.[6][19]

Katsuren Peninsula

The Katsuren Peninsula extends south from Okinawa Island and used to be incorporated as the town of Katsuren. The peninsula extends 7.5 kilometres (4.7 mi) from the island, is 1.7 kilometres (1.1 mi) to 2.6 kilometres (1.6 mi) wide, and covers 15 square kilometres (5.8 sq mi). The peninsula is the home base for access to the Yokatsu Islands, as well as home to two U.S. military facilities, Camp Courtney and White Beach.[22]

Yokatsu Islands

The eight Yokatsu Islands are located in Uruma City. Seven sit to the east of the Katsuren Peninsula, and one, Tsuken Island, sits to the southeast.[4]

- Yabuchi Island (藪地島, Yabuchi-jima) is one of the Yokatsu Islands located on the east of the Katsuren Peninsula. The island covers 0.62 square kilometres (0.24 sq mi). The island maintained a population until three hundred years ago, but is now uninhabited. Part of the Yabuchi is used for rice cultivation. Yabuchi Island is well known for its large population of habu, the poisonous pit viper of Okinawa, and its southern coast is dense with kasanori, and Okinawan species of Ulvophyceae, an edible algae. The island is home to the Yabuchi Cave Ruins, first excavated in 1959. The ruins produced a shard of pottery dating approximately 6,500 years ago. The pottery is the first of its kind of Okinawa, and the style is now called yabuchi-style pottery. The caves are home to numerous shrines associated with ancestor worship of the Ryukyuan religion.[23][24]

- Henza Island (平安座島, Henza-jima) is located 3.5 kilometres (2.2 mi) off the Katsuren Peninsula and covers 5.22 square kilometres (2.02 sq mi).[20] The majority of the island is used as an oil tank facility. The population of Henza Island is concentrated at the entrance of the island, which includes a fishing port. The island is connected to the mainland by the Mid-Sea Road, which forms part of Okinawa Prefectural Road 10. Prior to the construction of the Mid-Sea Road the channel could be crossed by foot or amphibious vehicle at low tide. Henza Island is bisected from northwest to southeast by flat limestone ridge that ranges between 65 metres (213 ft) and 90 metres (300 ft) in height. The island has little arable land, but is surrounded by rich fishing areas along its coral reefs.[25]

- Miyagi Island (宮城島, Miyagi-jima), also known as Takahari Island (高離島, Takahari-jima), is adjacent to the northeast coast of Henza Island. The two islands used to be separated by a shallow beach, but are now connected via landfill. The island covers 5.51 square kilometres (2.13 sq mi). The island relies on the tourism industry, but also produces sugarcane and cut flowers. The irregular geological formation of the island cause numerous natural springs, notably in the northeast of the island. Miyagi has numerous historical remains, including the remains of one gusuku, the Tomari Gusuku.[26]

- Ikei Island (伊計島, Ikei-jima), also known as Ichihanari to residents of the island, is the easternmost of the Yokatsu Islands. It is connected to the northeastern tip of Miyagi Island by the short Ikei Ōhashi Bridge.[27] The island covers 1.7 square kilometres (0.66 sq mi) and has a coastline of 7.5 kilometres (4.7 mi). The north, west, and south coasts of the island consist of inaccessible steep cliffs, which range between 20 metres (66 ft) and 30 metres (98 ft).[27] Ikei Island is relatively flat. The main settlement is on the west of the island. Ikei Island used to be home to numerous sugarcane farms, but the economy is now focused almost entirely on the tourism industry.[27] Ikei Island has numerous archaeological sites, including shell mounds and the remains of a castle, the Ikei Gusuku. The island, which was sighted by Commodore Matthew Calbraith Perry (1794–1858), was recorded as "Ichey Island" in the Narrative of the Expedition of an American Squadron to the China Seas and Japan, published in 1856 by Francis L. Hawks.

- Hamahiga Island (浜比嘉島, Hamahiga-jima), also known as Bamahija-jima, sits 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) from the Katsuren Peninsula directly south of Henza Island. The island is connected to Henza island by the 1.43 kilometres (0.89 mi) Hamahiga Bridge. The island is roughly triangular in shape covers 2.04 square kilometres (0.79 sq mi). Hamahiga Island measures 1.7 kilometres (1.1 mi) from east to west and 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) from north to south, and at its highest point reaches an elevation of 78.7 metres (258 ft). The island has an uneven topography with few natural inlets. The three settlements on the island are Hama on the northwest coastline, Higa on the northeast coastline, and Kaneku on the southeast coastline. Hama is home to the post office and middle school of Hamahiga Island, and the elementary school sits between Hama and Higa. All three settlements are home to a fishing port. Like the other Yokatsu Islands, Hamahiga has numerous shellmound and gusuku remains, but little archaeological excavation has been carried out on the island. Hamahiga is home to numerous sites of worship of the Ryukyuan religion, including the tombs of Amamikyu and Shinerikyu. The settlements of Hama and Higa are home to noro priestesses.[28]

- Tsuken Island (津堅島, Tsuken-jima, Okinawan: Biti)[29] is located 3.8 kilometres (2.4 mi) south south-east of the Katsuren Peninsula. The island covers 1.88 square kilometres (0.73 sq mi). Tsuken runs 2.3 kilometres (1.4 mi) from north to south and .8 kilometres (0.50 mi) to 1.3 kilometres (0.81 mi) east to west, and has its highest point in the southwest of the island at 38.8 metres (127 ft). Tsueken was once covered with a dense forest of fountain palms, but the middle portion of Tsuken was entirely burned during World War II, and palm groves remain only at the north of the island.[30] Thick belts of vegetation now exist around coastal areas of the island protect the settlement and agricultural land from Sea breeze. The only settlement on Tsuken is located in the southwest of the island, which is home to a post office, medical clinic, an elementary school, and a middle school. Tsuken is noted for its production of carrots. Commodore Perry recorded the island as "Taking Island" in his narrative. Tsuken is home to numerous shell mounds, of which three have been excavated. The island was also home to a castle, the Kubō Gusuku.[31] The Tsukenjima Training Area is used by the U.S. Military and is located off the western coast of Tsuken. The training area was established in 1959 and covers 16,000 square metres (170,000 sq ft).[32][33]

- Ukibara Island (浮原島, Ukibara-jima) is an uninhabited, low-lying island 2.7 kilometres (1.7 mi) southeast of Hamahiga Island. The island covers 0.3 square kilometres (0.12 sq mi), and measures 0.8 kilometres (0.50 mi) from east to west and 0.6 kilometres (0.37 mi) north to south. Ukibara is primarily flat, it reaches an altitude of 12 metres (39 ft). The island composed of quaternary Ryukyu limestone. Numerous coral reefs surround the island, and are notably well developed off the southwest coast of the island. Ukibara has no arable land and is mostly covered in dense cogon grass. Ukibara is now used as a training ground for the U.S. Marines Okinawa forces. The Marines maintain no permanent residential facilities on the island, and use the training ground periodically rather than permanently. Public access to Ukibara is prohibited.[34][35]

- Minamiukibara Island (南浮原島, Minamiukibara-jima) is an uninhabited island 1.2 kilometres (0.75 mi) south of Ukibara Island. It covers 1 square kilometre (0.39 sq mi).[34]

Arts and culture

Festivals

The Uruma City Festival is held in October, and is the largest festival in the city. It features bullfighting, performing arts, and live concerts.[36]

Community centers

Uruma has three communities centers, each of which have facilities for performances, cooking classes, and other cultural events. They are located in the Ishikawa Akebono, Katsuren Henna, and Yonashiro Yakema districts.[7]

Libraries

The Uruma City Library maintains three branches. The Main Library (formerly the Gushikawa Library) is in the Tairagawa district, and was built in 1989. The Ishikawa Library, located in the Akebono district, was built in 1990. The Katsuren Library, located in Katsurenhenna, was built in 1997. The libraries collectively hold 391,359 volumes.[37]

Recreation

The largest park in Uruma, the Agena Central Park, is located near the historical remains of Agena Castle. The castle and its moat make up the central part of the park. Agena Central Park is home to the Agena Bullfighting Ring.[38]

The Ayahashi Road Race Through the Sea Tournament is held in April. The race is divided into 3.8 kilometres (2.4 mi), 10 kilometres (6.2 mi), and half marathon runs. Runners cross from Yonashiro over the Mid-Sea Road, which is partially closed to traffic during the race, to Henza Island.[36][39]

Religion

Uruma is home to numerous sites associated with the Ryukyuan religion, many of which are located on the Yokatsu Islands. Hamahiga Island is located approximately 7 kilometres (4.3 mi) northeast of Kudaka Island, which is considered the holiest place of the Ryukyuan religion. The tombs of Amamikyu and Shinerikyu are located on Hamahiga. Amamikyu and Shinerikyu are worshipped at their tombs, and the noro priestess of Higa conducts prayers at the beginning of the year at the sites. The forests of the southeast tip of Hamahiga are home to a cave that is considered one of the residences of Amamikyu and Shinerikyu; a stalactite in a cave at the site is a center of worship for numerous children.[24] Nearby are other holy sites related to Shinerikyu, Maitreya, and Nirai Kanai (most notably the Miruku Gate and Mount Yugafu).

There are a significant number of noro priestesses and yuta mediums on Hamahiga Island, the latter being typically female, but sometimes male.[24]

Government

Uruma is administered from the city hall in Bikuni. The Uruma Board of Education oversees the middle school, elementary schools, and community education centers of the city.

The Uruma City Council consists of 34 members who serve a four-year term, and are led by a chairperson (Kazuo Nishino, born 1950) and vice-chairperson (Mitsuo Higashihama, born 1954) of the council. City council members are affiliated with the Okinawa Social Mass Party, the Shinsei Club, the New Komeito Party, the Japan Revolutionary Communist League, the Japanese Communist Party, and the 21st Century Club.[40]

Uruma has eleven post offices: one each in Gushikawa, Agena, Shirinkawa, Higashi Gushikawa, Ishikawa, Ishikawa Shiromae, Ishikawa Higashionna, Yokatsu, Katsuren, Henza, and Yonashiro. The city maintains two police stations: Uruma Police Station and Ishikawa Police Station. Fire stations for the city are located in Gushikawa, Ishikawa, Katsuren, and Henza.

Education

The City of Uruma maintains 17 elementary schools (Miyamori, Shiromae, Iha, Yonashiro, Minamihara, Katsuren, Heishikiya, Higa, Tsuken, Kawasaki, Tengan, Agena, Taba, Gushikawa, Kanehara, Nakahara, Akamichi, and Ayahashi), and 9 middle schools (Ishikawa, Iha, Tsuken, Yokatsu, Yokatsu 2nd, Agena, Gushikawa, Takaesu, and Gushikawa East). The city closed and consolidated numerous elementary and middle schools in 2012. In addition, Uruma maintains 18 preschools.[41]

Bechtel Elementary School, located on Camp McTureous, is administered by Department of Defense Education Activity for English-speaking United States military dependents. It is run under the supervision of the Okinawa Department of Defense Dependents Schools District.[42]

The senior high schools of Uruma are operated by Okinawa Prefecture. Okinawa Prefectural Yokatsu Senior High School-Yokatsu Midorigaoka Junior High School is a joint secondary school in the Katsuren Henna district.[43] Other senior high schools include Ishikawa Senior High School, Gushikawa Senior High School, Maehara Senior High School, Gushikawa Commercial Senior High School, and Chūbu Agricultural High School.

Transportation

Bus

Uruma is connected to the other municipalities of Okinawa Island by transit bus with numerous routes originating from the Naha Bus Terminal. The four bus companies that serve Okinawa, Ryukyu Bus, Okinawa Bus, Naha Bus Co., Ltd., and Toyo Bus, all have lines in Uruma, but service via Naha Bus is limited to the jointly operated high-speed bus Route 111. JA Okinawa operates local buses to the Katsuren Peninsula and the Yokatsu Islands.

Ryukyu Bus operates the Gushikawa Bus Terminal, Okinawa Bus operates the Yakena Bus Terminal, which is also used by Ryukyu Bus, and Toyo Bus operates the Toyo Bus Awase Office.

Highway

The Okinawa Expressway, which runs 57.3 kilometres (35.6 mi) from Naha to Nago, has one interchange in Uruma, the Ishikawa Interchange. Japan National Route 329, which similarly runs between Naha and Nago, runs through the western districts of Uruma. The city, including the Yokatsu Islands, is also served by numerous prefectural highways.

Port of Kinwan

The Port of Kinwan (19,400 hectares (48,000 acres)) encompasses the coastal areas of Naha, Uruma, and other municipalities on Okinawa island. The port area covers the entirety of the coastal areas of Uruma, including those of the Yokatsu Islands.[44]

Hospital

Okinawa Prefectural Chūbu Hospital is located in the Miyazato district of Uruma. The hospital traces its history to the refugee camps in 1945, which were staffed by personnel from the University of Hawaii. Chubu Hospital was formally established in 1946, and is one of 6 prefectural hospitals in Okinawa Prefecture, and maintains a strong reciprocal training agreement with the University of Hawaii.[45][46]

Noted places

Uruma is noted for several historic and religious sites, including the Iha Shell Mound, Katsuren Castle, and Agena Castle.

Iha Shell Mound

The Iha Shell Mound is located in the Iha district of Uruma. The site sits on a large limestone fault slope, and dates from the late Jōmon period, ca. 2500 – 1000 BC. The Iha Shell Mound is approximately 60 centimetres (24 in) thick and covers an area of 150 square metres (1,600 sq ft).[47] The site was first discovered in 1920, and is one of only a few fully excavated shell mounds in Okinawa. The site includes remains of fish and animal bones, earthen and stoneware, and goods made out of horn.[6]

Agena Castle

Agena Castle is a gusuku located in the north of Agena district of Uruma, in former Gushikawa City. It was built on a base of Ryūkyūan limestone and occupies 8,000 square metres (86,000 sq ft). Agena Castle sits at an altitude of 49 metres (161 ft), and is naturally protected by the Tengan River to the north.[48] The Ōgawa Aji, or regional ruler of the Ōgawa Magiri of the Ryūkyū Kingdom, occupied the castle for several generations. For this reason the castle is also known as the Ōgawa gusuku. Details of the history of both the castle and the aji are unclear, and no archaeological excavation has been carried out on the castle. It was likely built in the 14th century.[48] The Ōgawa reached their greatest period of prosperity in the 15th century.[49] At some point the castle was destroyed by the army of the Ryūkyū Kingdom. The outer gate of Agena Castle no longer exists, but as the inner gate is bored through the limestone foundation and is surrounded on both sides with quarried rocks, it still exists. The inner gate is an early example of an arched castle gate, and is protected as a national treasure of Japan. The castle remains now hold numerous utaki sites of worship of the Ryukyuan religion, and are scattered with fragments of Chinese ceramics from the 14th to the 15th century.[49] The area around the castle is now used as Agena Park.[48][49]

Katsuren Castle

Katsuren Castle is a gusuku, or Okinawan castle, in former Katsuren Town.[50] The castle is known as Kacchin Gushiku in the Okinawan language. It sits 98 meters (322 ft) above sea level on the small Katsuren Peninsula, and is flanked by the Pacific Ocean on two sides.[50] The "golden age" of Katsuren Castle was in the mid-15th century, when the castle was controlled by the Aji of Katsuren, Amawari (died 1458), before his death in conflicts with Shō Taikyū (1415–1460) of Shuri and Gosamaru (died 1458), Aji of Nakagusuku Castle.[51][52][53][54] Katsuren Castle has an active shrine of the Ryukyuan religion within its first bailey.[55] In the 2010 Okinawa earthquake damaged an outer wall at the northeast of the third bailey of the castle.[56] Katsuren Castle was designated a Designated Historical Monument in 1972, and designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2000 as part of one of the nine Gusuku Sites and Related Properties of the Kingdom of Ryukyu.[57]

U.S. military bases

United States military bases in Uruma cover 6.632 square kilometres (2.561 sq mi), or 12.97% of the total area of the city. While the bases are located on a mix of national, prefectural, municipal, and private property, 4.964 square kilometres (1.917 sq mi), or 75% of base areas are on privately held land.[58]

Kadena Ammunition Storage Area

The Kadena Ammunition Storage Area (26.579 square kilometres (10.262 sq mi)) is the third largest military base in Okinawa Prefecture, and spans the municipalities of Okinawa City, Kadena, Yomitan, Onna, and Uruma. While it covers fully 1.877 square kilometres (0.725 sq mi) in Uruma and is the largest base area in the city, it represents only 7% of the total size of the base.

Camp Courtney

Camp Courtney is a United States Marine Base located in the north of Uruma on Kin Bay. The camp was established in 1956 and occupies 1.348 square kilometres (0.520 sq mi) in the Konbu, Tengan, and Uken districts of Uruma.[59] Camp Courtney is part of the larger Marine Corps Base Camp Smedley D. Butler, and is home to the quarters of the 3rd Marine Division Headquarters and the III Marine Expeditionary Force. Camp Courtney is utilized for office space and living quarters for Marines and military families. The camp includes a post office, theater, bank, church, and recreational facilities.[59][60]

Camp McTureous

Camp McTureous is a United States Marine Base located in the west side of the Agena district of Uruma. The camp was established in 1956 and occupies 1.348 square kilometres (0.520 sq mi) in the Kawasaki district of Uruma.[59] Camp McTureous is part of the larger Marine Corps Base Camp Smedley D. Butler. Camp McTureous is utilized for living quarters for Marines and military families. The camp includes Bechtel elementary school and recreational facilities.[61]

White Beach Naval Facility

White Beach Naval Facility, formally referred to as the Port Operations Naval Facility White Beach, is a United States Navy base located southern tip of the Katsuren Peninsula at the Northeast of Nakagusuku Bay, also known as Buckner Bay. The base covers 1.568 square kilometres (0.605 sq mi) in the Heishikiya and Nohen districts of the city.[62][63] White Beach serves as the staging area for the Okinawa-based 31st Marine Expeditionary Unit.[62][64][65][66] Nuclear submarines and warships and submarines make regular calls to the facility.[66] White Beach consists primarily of two piers, designated Navy Pier and Army Pier.[67] The Navy pier is 24 metres (79 ft) in width and 850 metres (2,790 ft) in length, and the Army pier is 24 metres (79 ft) in width and 450 metres (1,480 ft) in length.[67] The Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force Okinawa Naval Base is located directly adjacent to White Beach.

The White Beach Naval Facility was built at the end of the Battle of Okinawa in 1945. 95,000 military engineers arrived on Okinawa Island to convert the island into a staging area for an invasion of the Japanese main islands. While the island was not used for an invasion of Japan, White Beach remained a permanent military facility.[68][69] White Beach played a role in the controversial Agent Orange testing in Okinawa in the early 1960s under an American program to test unconventional weapons as part of the classified Project AGILE. Logbooks of the privately owned merchant marine ship SS Schuyler Otis Bland show that chemicals agents were delivered to White Beach under armed guard on April 25, 1962, then transported to other areas of the island.[8][9][10]

Famous people from Uruma

- Takashi Chinen, gymnast

- Finger 5, musical group

- Manami Higa, actress

- HY, band

- Seijin Noborikawa, singer

- Kichiro Shimabuku, first son of Tatsuo Shimabuku

- Tatsuo Shimabuku, founder of Isshin-ryu karate

- Denny Tamaki, governor of Okinawa Prefecture

- Takato Toguchi, boxer

- Tenkai Tsunami, female professional boxer

- Ayano Uema, singer

- Mugi the Cat, musician

See also

1959 Kadena Air Base F-100 crash

References

- ^ a b 石川岳 [Ishikawadake] (in Japanese). Tokyo: Yama-kei Publishers Co., Ltd. 2012. Retrieved Jan 8, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f "うるま" [Uruma]. Dijitaru Daijisen (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. OCLC 56431036. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2012-12-14.

- ^ a b c d "うるま(市)" [Uruma]. Nihon Daihyakka Zensho (Nipponika) (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. OCLC 153301537. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2012-12-14.

- ^ a b "与勝諸島" [Yokatsu Islands]. Nihon Daihyakka Zensho (Nipponika) (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2013. OCLC 153301537. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2013-04-04.

- ^ "海中道路" [Mid-Sea Road]. Naha, Okinawa Prefecture, Japan: Okinawa Info IMA. 2005. Retrieved 2013-05-09.

- ^ a b c d e "Ishikawa". Encyclopedia of Japan. Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. OCLC 56431036. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2012-12-20.

- ^ a b c "Information from Uruma City" (in Japanese). Uruma, Okinawa Prefecture, Japan: City of Uruma. 2005. Retrieved Dec 26, 2012.

- ^ a b Mitchell, Jon (17 May 2012). "Agent Orange 'tested in Okinawa'". Japan Times. Tokyo: Japan Times, Ltd. Retrieved 2013-03-06.

- ^ a b Mitchell, Jon (7 Aug 2012). "25,000 barrels of Agent Orange kept on Okinawa, U.S. Army document says". Japan Times. Tokyo: Japan Times, Ltd. Retrieved 2013-03-06.

- ^ a b Lobel, Phillip; Schreiber, Elizabeth A.; McClosky, Gary; O'Shea, Leo (2003). Harris, Robert; Richlin, Mindy (eds.). An Ecological Assessment of Johnston Atoll. Edgewood, Md.: U.S. Army Chemical Materials Activity. p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-09-15. Retrieved 2013-03-06.

- ^ "Uruma no meishō sentei riyū ni tsuite (うるまの名称選定理由について)" (in Japanese). Uruma City Official Web Site. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- ^ "Uruma-shi no imi (うるま市の意味)" (in Japanese). Uruma City Official Web Site. Archived from the original on 14 March 2015. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

- ^ Yara Ken'ichirō 屋良健一郎 (2013). "Ryūkyū-jin to waka 琉球人と和歌". In Tōkyō daigaku daigakuin jinbun shakai-kei kenkyūka Nihonshigaku kenkyūshitsu 東京大学大学院人文社会系研究科・文学部日本史学研究室 (ed.). Chūsei seiji shakai ronsō 中世政治社会論叢 (in Japanese). pp. 73–85.

- ^ a b "美里間切" [Misato magiri]. Nihon Rekishi Chimei Taikei (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2013. OCLC 173191044. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2013-04-17.

- ^ a b "具志川間切" [Gushichaa magiri]. Nihon Rekishi Chimei Taikei (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2013. OCLC 173191044. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2013-04-17.

- ^ "Action in the North, Chp 6 of Okinawa: Victory in the Pacific by Major Chas. S. Nichols, Jr., USMC and Henry I. Shaw, Jr". Historical Section, Division of Public Information, U.S. Marine Corps. Archived from the original on April 13, 2010. Retrieved May 7, 2010.

- ^ ひまわり [Himawari] (in Japanese). "Himawari Okinawa wa Wasurenai Ano hi no sora o" Seisaku Iinkai. 2012. Retrieved Dec 18, 2012.

- ^ "Movie featuring the U.S. military aircraft crash onto Miyamori Elementary School screened". Ryukyu Shinpo. Naha, Okinawa Prefecture, Japan: Ryukyu Shimpo Co. Ltd. Dec 9, 2012. Retrieved Dec 20, 2012.

- ^ a b "Gushikawa". Encyclopedia of Japan. Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. OCLC 56431036. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2012-12-14.

- ^ a b 沖縄の島面積 [Land Area of the Islands of Okinawa] (in Japanese). Tsukuba, Ibaraki, Japan: Geospatial Information Authority of Japan. 2007. Archived from the original on May 5, 2012. Retrieved December 23, 2012.

- ^ 天願川 [Tengan River] (in Japanese). Naha, Okinawa Prefecture: Okinawa Prefecture. 2012. Retrieved 2013-01-29.

- ^ "勝連半島" [Katsuren Peninsula]. Nihon Rekishi Chimei Taikei (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. OCLC 173191044. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2012-12-07.

- ^ "藪地島" [Yabuchi Island]. Nihon Daihyakka Zensho (Nipponika) (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. OCLC 153301537. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2012-12-22.

- ^ a b c スピリチュアル [Spiritual life] (in Japanese). Uruma, Okinawa Prefecture, Japan: City of Uruma. 2009. Archived from the original on July 31, 2012. Retrieved December 22, 2012.

- ^ "平安座島" [Henza Island]. Nihon Rekishi Chimei Taikei (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. OCLC 173191044. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2012-12-07.

- ^ "宮城島" [Miyagi Island]. Nihon Rekishi Chimei Taikei (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. OCLC 173191044. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2012-12-07.

- ^ a b c 伊計大橋 [Ikei Ōhashi] (PDF). 宿道 (in Japanese). 30. Urasoe, Okinawa Prefecture, Japan: Okinawa Shimatate Kyōkai: 2. March 2009. Retrieved 2013-01-07.

- ^ "浜比嘉島" [Hamahiga Island]. Nihon Rekishi Chimei Taikei (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. OCLC 173191044. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2012-12-28.

- ^ "ビティ島" [Biti-shima]. Okinawa Wiki (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2013. OCLC 173191044. Retrieved 2013-04-13.

- ^ Okinawa Rekishi Kenkyūkai, ed. (1994), 沖繩の歴史散步, Shin zenkoku rekishi sanpo shirīzu (in Japanese), vol. 47 (Shinpan 1-han ed.), Tōkyō: Yamakawa Shuppansha, p. 109, ISBN 9784634294707, OCLC 31267327

- ^ "津堅島" [Tsuken Island]. Nihon Rekishi Chimei Taikei (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. OCLC 173191044. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2012-12-07.

- ^ "津堅島訓練場". Nihon Rekishi Chimei Taikei (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. OCLC 173191044. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2012-12-07.

- ^ "津堅島訓練場 (FAC6082 Tsuken Jima Training Area)" [FAC6082 Tsuken Jima Training Area] (in Japanese). Uruma, Okinawa Prefecture, Japan: City of Uruma. 2005. Retrieved Dec 28, 2012.

- ^ a b "浮原島" [Ukibara Island]. Nihon Rekishi Chimei Taikei (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. OCLC 173191044. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2012-12-07.

- ^ "浮原島訓練場" [Ukibara Training Ground]. Nihon Rekishi Chimei Taikei (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. OCLC 173191044. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2012-12-07.

- ^ a b "City Festivals and Events" (in Japanese). Uruma, Okinawa Prefecture, Japan: City of Uruma. 2012. Retrieved Dec 26, 2012.

- ^ うるま市立図書館 [Uruma City Library] (in Japanese). Uruma, Okinawa Prefecture, Japan: Uruma City Library. 2007. Retrieved Jan 5, 2013.

- ^ 安慶名中央公園について [About Agena Central Park] (in Japanese). Uruma, Okinawa Prefecture, Japan: Agena Chūō Kōen e Go!. 2007. Archived from the original on January 8, 2013. Retrieved January 8, 2013.

- ^ Myers, Jannine (2012). "Ayahashi On-The-Sea Road Race". Tokyo, Japan: JapanTourist.com. Retrieved Dec 26, 2012.

- ^ うるま市議会 [Uruma City Council] (in Japanese). Uruma, Okinawa Prefecture, Japan: City of Uruma. 2012. Retrieved Jan 5, 2013.

- ^ うるま市立学校一覧 [Summary of the Schools of the City of Uruma] (in Japanese). Uruma, Okinawa Prefecture, Japan: City of Uruma. 2012. Retrieved Dec 19, 2012.

- ^ "Bechtel Elementary School". Alexandria, Va.: Department of Defense Education Activity. 2012. Retrieved Dec 20, 2012.

- ^ 沖縄県立与勝緑が丘中学校・与勝高等学校 [Okinawa Prefectural Yokatsu Senior High School-Yokatsu Midorigaoka Junior High School] (in Japanese). Uruma, Okinawa Prefecture, Japan: Okinawa Prefectural Yokatsu Senior High School-Yokatsu Midorigaoka Junior High School. 2013. Retrieved 2013-04-13.

- ^ 金武湾港 [Port of Kinwan] (in Japanese). Naha, Okinawa Prefecture, Japan: Okinawa Prefecture. c. 2012. Retrieved Dec 21, 2012.

- ^ 病院沿革 [Hospital Timeline] (in Japanese). Uruma, Okinawa Prefecture, Japan: Okinawa Prefectural Chubu Hospital. 2010. Retrieved 2013-02-19.

- ^ 沖縄県内6つの県立病院を紹介します [Introduction to the Six Prefectural Hospital of Okinawa] (in Japanese). Naha, Okinawa Prefecture, Japan: Okinawa Prefecture. 2006. Retrieved 2013-02-19.

- ^ "Iha Shell Mound". Encyclopedia of Japan. Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. OCLC 56431036. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2012-12-14.

- ^ a b c "安慶名城" [Agena Castle]. Nihon Rekishi Chimei Taikei (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2013. OCLC 173191044. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2013-01-29.

- ^ a b c "安慶名城" [Agena Castle]. Nihon Daihyakka Zensho (Nipponika) (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. OCLC 153301537. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2012-12-14.

- ^ a b "Katsuren-gusuku". Nihon Rekishi Chimei Taikei (日本歴史地名大系 "Compendium of Japanese Historical Place Names") (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2012-12-19.

- ^ "尚泰久" [Shō Taikyū]. Kokushi Daijiten (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2013. OCLC 683276033. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2013-01-30.

- ^ "護佐丸" [Gosamaru]. Nihon Jinmei Daijiten (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2013. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2013-12-30.

- ^ "阿麻和利" [Amawari]. Nihon Jinmei Daijiten (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2013. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2013-01-30.

- ^ Kerr, George (2000). Okinawa, the history of an island people. Boston, MA: Tuttle Pub. pp. 98–99. ISBN 0804820872.

- ^ "Gusuku Sites and Related Properties of the Kingdom of Ryukyu". Paris, France: UNESCO. Retrieved 2013-01-30.

- ^ 沖縄本島近海地震世界遺産の城壁が一部崩落勝連城跡 Archived 2012-11-14 at the Wayback Machine(in Japanese)

- ^ 勝連城跡・文部科学省文化庁(in Japanese)

- ^ うるま市における基地の概況 [Overview of Bases in the City of Uruma] (in Japanese). Uruma, Okinawa Prefecture, Japan: City of Uruma. 2005. Retrieved 2012-04-05.

- ^ a b c "キャンプ・コートニー" [Camp Courtney]. Nihon Rekishi Chimei Taikei (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. OCLC 173191044. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2012-12-07.

- ^ "Camp Courtney, Okinawa, Japan". Globalsecurity.org. 2012. Retrieved Dec 19, 2012.

- ^ "キャンプ・マクトリアス" [Camp McTureous]. Nihon Rekishi Chimei Taikei (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. OCLC 173191044. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2012-12-07.

- ^ a b "ホワイト・ビーチ地区" [White Beach Naval Facility]. Nihon Rekishi Chimei Taikei (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2013. OCLC 173191044. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2013-02-13.

- ^ "SDDC Almanac 2012" (PDF). Washington, D.C.: Military Surface Deployment and Distribution Command. 2012. p. 33. Retrieved 2013-03-05.

- ^ "Commander Fleet Activities Okinawa Operations". Okinawa, Japan: Commander Fleet Activities Okinawa. 2013. Retrieved 2013-02-12.

- ^ "Installation Guide". Okinawa, Japan: Commander Fleet Activities Okinawa. 2013. Retrieved 2013-02-12.

- ^ a b "White Beach Naval Facility, Okinawa, Japan" (in Japanese). Alexandria, Va.: Globalsecurity.org. 2001. Retrieved 2013-02-08.

- ^ a b Handlers, G.; Brand, S. (2001). Buckner Bay (2011 Rev. ed.). Monterey, California: United States Naval Research Laboratory. Retrieved 2013-03-02.

- ^ Rottman, Gordon (2002). Okinawa 1945 : the last battle. Oxford: Osprey Pub. ISBN 9781855326071.

- ^ Sloan, Bill (2008). The ultimate battle : Okinawa 1945—the last epic struggle of World War II. New York: Simon & Schuster Paperbacks. p. 329. ISBN 9780743292474.

External links

Media related to Uruma, Okinawa at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Uruma, Okinawa at Wikimedia Commons- Uruma City official website

- Uruma City official website