William Wailes

William Wailes (1808–1881) was the proprietor of one of England's largest and most prolific stained glass workshops.

Life and career

Wailes was born and grew up in Newcastle on Tyne, England's centre of domestic glass and bottle manufacturing. His first business was as a grocer and tea merchant.[1] However, his artistic talent and practical skills led him to set up a small kiln in the backyard of his premises. He made and fired small decorative enamels which were sold in his shop.

In 1830 he went to Germany to study stained glass design and production under Mayer of Munich. In 1838 he set up his own stained glass studio to design and manufacture windows[2] and in 1841 the business began producing its own glass.

In 1842 the architect Augustus Pugin approached Wailes about producing windows for him. Working with Pugin was a thankless task, as Pugin went from one workshop to another in an attempt to get his designs realised at the lowest possible cost. The working relationship lasted for only three years.[3]

Regardless of this, Wailes made a name for himself through the provision of windows for local churches. As his enterprise prospered, he employed more men until there were 76 employees, who included in their number several designers who were to go on to establish their own factories. These included Francis Wilson Oliphant R.A. (1818–1859) and George Joseph Baguley (1834–1915). William Wailes was one of the twenty-five stained glass manufacturers that exhibited in the Crystal Palace Exhibition in 1851.

Wailes married (Elizabeth) and they had several children, including a son, William Thomas Wailes, who was to join his father in the business, as did his son-in-law, Thomas Rankine Strang,[2] in 1861, when the firm became known as Wailes and Strang.

In 1860 Wailes bought the Saltwell Estate at Gateshead and set about improving it, building himself a decorative mansion and landscaping the grounds. Unfortunately, he ran into debt and 16 years later sold the property to the Gateshead Corporation. The estate became a public park known as Saltwell Park which includes the house, Saltwell Towers. However Wailes continued to reside in his home until his death in 1881. William Thomas Wailes continued to manufacture stained glass until 1910.

Artistic recognition

Wailes was painted, next to a window exemplifying his work, by John Oliphant. The painting hangs in the Shipley Art Gallery in Gateshead.[4]

Stained glass

Style

Although William Wailes employed a number of designers, the products of his workshop are often identifiable by type of glass and the particular colour combinations that prevailed. Wailes’ glass is often a little paler and more brightly coloured than many English workshops of the same date, being rather more like glass from Germany or Limoges. There are certain distinctive colour combinations that occur repeatedly in the clothing of figures in Wailes’ windows- mauve lined with bright red, yellow lined with bright blue, red lined with acid green. Many of Wailes window contain a great deal of pink glass.

Although Wailes was seen as a Gothic Revival artist, and was able to fill windows with ornate foliate patterns that have the quality of brightly painted manuscripts rather than ancient glass, his figures were elegantly classicising and decidedly staid of demeanour. Figures in Wailes’ windows communicate in a series of stereotypical hand gestures. Moreover, the details of faces are applied in a painterly manner, as against the almost calligraphic manner with which some of the 19th-century artists such as John Hardman imitated ancient windows. The painterly manner is typical of that employed by Mayer of Munich, with whom Wailes trained.

Gloucester Cathedral

While most of the work of Wailes' workshop is to be found in the North of England, other commissions came from further afield. The most significant window glazed by the firm, and one of the prize commissions of the industry, was the glazing of the west window of Gloucester Cathedral, an enormous window of c.1430 in the Perpendicular Gothic style, of nine lights and four tiers. This window complemented, at the other end of the building, one of the largest ancient windows in the world; the east window (which is as big as a tennis court) fortunately had retained much of its 14th century glass, comprising many tiers of figures.

Wailes' west window at Gloucester is a stupendous achievement, and not just because of the technicalities involved in glazing such a vast area. It makes no attempt to imitate the style or content of the east window. The content of the west window, like that of so many other commissions, was probably stipulated by a committee. Because the window was so large there was room for a large number of narratives and many figures.

The window comprises nine vertical sections called lights which are divided by mullions into three lots of three. The window rises in three stages, the first and the third being approximately half as tall as the middle one, the whole being surmounted by many smaller vertical tracery lights, which Wailes predictably filled with singing angels neatly arranged in robes of violet, bright red and arsenic green.

Wailes' design divides the window's main part into four rather than three stages, each containing three complex narrative scenes which are made successfully to span three lights. The central section which shows the Nativity of Christ with the Baptism of Christ in the Jordan by John the Baptist (one below the other) is a particularly successful composition, considering that it contains two significant narrative incidents which visually harmonise, yet remain discrete scenes. While each of the twelve individual pictures works as a unit, the visual composition of the whole window is skilfully arranged so as to present as an integrated work of art. This has been achieved by the skilled placement of the 116 figures and the equally skilful disposition of colour.

Churches containing stained glass by William Wailes

- St Lawrence, Waltham, Kent – East window, Crucifixion, Resurrection and Ascension, 1847

- St Andrew's, Bradfield – 12 windows with stories from the Gospels, 1848

- Chichester Cathedral – 5-light window of Christ and the four Gospel writers, 1849

- St James', Devizes – East window, 1849[5]

- Bridlington Priory – East and west windows, 1849[6] Also S aisle W window 1854[7]

- All Saints Church, Huntsham, Devon, 1856

- St Botolph, Farnborough – East window, 1856

- St Mary's, Thatcham – East window, Feeding of the Five Thousand, 1858

- All Saints', Hursley – An important commission of a complete cycle of 21 windows, showing The Crucifixion at the east end, with the Resurrection and Presentation in the Temple. At the west is Christ in Judgement. Along the south side are Apostles and Doctors of the Church, on the north are Prophets and Ancestors of Christ, 1858

- Church of St John the Evangelist, better known as the Afghan Church, Mumbai – East and West windows, 1858[8]

- Gloucester Cathedral – West window: the life of Christ with stories from the Old Testament and New Testaments, 9 lights, 1859[9]

- St George, Benenden – East window of 5 lights, Crucifixion and Passion, 1861

- St Martin's, Dorking – Chancel windows, 1867

- St Mary's, Chilham – East window of 5 lights, Crucifixion and Resurrection with other scenes, 1864. For full description see Poor Man's Bible.

- St Mary's, Clipsham, Rutland – East and west windows[10]

- St Mary's, Kingsclere, Hampshire. Transfiguration for Dr Thompson of Swan Street in the Sanctuary, aka Chancel aisle, now Kingsmill Room.

- Ss Peter and Paul, Great Missenden – East window, with angels and banners, 1850; chancel window, 1865

- Church of St Thomas, Thurstonland – East window, Good Samaritan, 1870[11]

- The First Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia houses five large windows highlighting the apse and depicting important events in the life of Jesus. The windows were imported and installed in 1872.

- St Helen's, Low Fell, Gateshead – 5 lancet windows in the apse depicting the Miracle of the Loaves and Fishes, the Healing of the Paralytic, the Ascension, Christ Blessing Little Children, the Sermon on the Mount, 1876

- St John's, Piddinghoe – 11 windows by Wailes and Strang, Gospel stories and Saints, 1882[12]

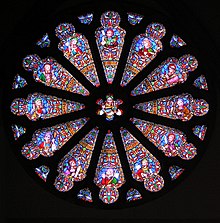

- St Matthias, Richmond, London – Wheel window of 12 Apostles, 1862, and 7 small narrative windows

- St John the Evangelist, Birtley, Co Durham – 2 windows in south nave: Nativity – 2 scenes: Annunciation & Visit of Shepherds, Resurrection – 2 scenes: Raising of Lazarus and Empty tomb[13]

- Church of St Editha, Tamworth – East window[14]

- St Helen Witton Church, Northwich – East window

- The Cathedral of The Isles, Millport, Cumbrae – West window

- St James the Less, Fradswell, Staffordshire

- St Edward's Church, Stow on the Wold, Gloucestershire[15]

- St Boniface Parish Church, Bonchurch, Isle of Wight – East window, scenes from the life of Christ

- St Mark's Hamilton Terrace, London NW8, large four-light window in the South Transept, 1850 (thought to have been exhibited at the Great Exhibition)

- Church of St Mary the Virgin, Ambleside – Hannah, Samuel and Eli[16]

- Holy Trinity, Sunderland (former Parish Church) – East window

- Church of St Anne, Catterick, North Yorkshire[17]

- Hexham Abbey, Northumberland – five windows including the great North Transept window showing the twelve apostles and New Testament scenes[citation needed]

- St George's Cathedral, Southwark[18] – most destroyed by bombing during WWII

- Christ Church St Laurence, Sydney, Australia – east window,[19] 1863–1905, parts subsequently preserved in west wall

See also

Other early 19th century firms

Context

- Stained glass

- Stained glass - British glass, 1811-1918

- Victorian Era

- Gothic Revival

- Poor Man's Bible

References

- ^ "Why Saltwell Park in Gateshead's Low Fell has long been a 'people's park' - Chronicle Live". 18 March 2021.

- ^ a b "William Wailes. (1838-1914) : Stained Glass in Wales".

- ^ Pugin also fell out with Thomas Willement and William Warrington

- ^ John Oliphant. "Portrait of William Wailes". Tyne & Wear Archives and Museums. Retrieved 11 June 2020.

- ^ Historic England. "Church of St James (1263715)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ^ "Geograph:: West window, Bridlington Priory © Julian P Guffogg cc-by-sa/2.0". www.geograph.org.uk. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ Buildings of England Yorkshire: York and the East Riding (2001 edition)

- ^ "Latest News & Dispatches on Politics, Social Issues, Economy".

- ^ "Stained glass in Gloucester Cathedral". Photo.Net. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ "Church of Saint Mary, Clipsham". Listed buildings. English Heritage. (quoting Pevsner)

- ^ Huddersfield Chronicle, 8 October 1870: Consecration of St Thomas' Church, Thurstonland Retrieved 1 May 2014

- ^ "St John the Evangelist, Piddinghoe, Sussex". Roughwood British Churches Album. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ^ "Stained Glass at St Johns". Birtley Parish Church. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ^ Lives of the Queens of England Archived 2010-05-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Parish church of Saint Edward". List Entry 1078369. English Heritage. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ^ "A Mother in Israel", Jean and Alexander Heard Library, Vanderbilt University

- ^ Pevsner, Nikolaus (2002). Yorkshire, the North Riding. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 119. ISBN 0-300-09665-8.

- ^ Bumpus, T. F., London Churches, Ancient and Modern, 2nd Series, 1907, p. 174.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "The Altar Window at Christ Church". The Sydney Morning Herald. Vol. XLIX, no. 8009. New South Wales, Australia. 9 February 1864. p. 4. Retrieved 10 October 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- Painton Cowen, A Guide to Stained Glass in Britain, 1985, Michael Joseph, ISBN 978-0-7181-2567-7

- Elizabeth Morris, Stained and Decorative Glass, Doubleday, ISBN 978-0-86824-324-5

- Sarah Brown, Stained Glass- an Illustrated History, Bracken Books, ISBN 1-85891-157-5

- Simon Jenkins, England's Thousand Best Churches, Allen Lane, the Penguin Press, ISBN 978-0-7139-9281-6

- John Harvey, English Cathedrals, Batsford, 1961, ISBN unknown

- Robert Eberhard, Church Stained Glass Windows, [1] [permanent dead link]

- Cliff and Monica Robinson, Buckinghamshire Stained Glass, [2]

- Victorian Wolverhampton, a town through its buildings, [3]