Spontaneous symmetry breaking

Spontaneous symmetry breaking in physics takes place when a system that is symmetric with respect to some symmetry group goes into a vacuum state that is not symmetric. At this point the system no longer appears to behave in a symmetric manner. It is a phenomenon that naturally occurs in many situations. The symmetry group can be discrete, such as the space group of a crystal, or continuous (i.e. a Lie group), such as the rotational symmetry of space.

A common example to help explain this phenomenon is a ball sitting on top of a hill. This ball is in a completely symmetric state. However, it is not a stable one: the ball can easily roll down the hill. At some point, the ball will spontaneously roll down the hill in one direction or another. The symmetry has been broken because the direction the ball rolled down in has now been singled out from other directions.

Mathematical example: the Mexican hat potential

In the simplest example, the spontaneously broken field is described by a scalar field. In physics, one way of seeing spontaneous symmetry breaking is through the use of Lagrangians. Lagrangians, which essentially dictate how a system will behave, can be split up into kinetic and potential terms

It is in this potential term (V(φ)) that the action of symmetry breaking occurs. An example of a potential is illustrated in the graph at the right.

This potential has many possible minima (vacuum states) given by

for any real θ between 0 and 2π. The system also has an unstable vacuum state corresponding to φ = 0. This state has a U(1) symmetry. However, once the system falls into a specific stable vacuum state (corresponding to a choice of θ) this symmetry will be lost or spontaneously broken.

In the Standard Model, spontaneous symmetry breaking is accomplished by using the Higgs boson and is responsible for the masses of the W and Z bosons. A slightly more technical presentation of this mechanism is given in the article on the Yukawa interaction, where it is shown how spontaneous symmetry breaking can be used to give mass to fermions.

Broader concept

More generally, we can have spontaneous symmetry breaking in nonvacuum situations and for systems not described by actions. The crucial concept here is the order parameter. If there is a field (often a background field) which acquires an expectation value (not necessarily a vacuum expectation value) which is not invariant under the symmetry in question, we say that the system is in the ordered phase and the symmetry is spontaneously broken. This is because other subsystems interact with the order parameter which forms a "frame of reference" to be measured against, so to speak.

If a vacuum state obeys the initial symmetry then the system is said to be in the Wigner mode, otherwise it is in the Goldstone mode.

Examples

- For ferromagnetic materials, the laws describing it are invariant under spatial rotations. Here, the order parameter is the magnetization, which measures the magnetic dipole density. Above the Curie temperature, the order parameter is zero, which is spatially invariant and there is no symmetry breaking. Below the Curie temperature, however, the magnetization acquires a constant (in the idealized situation where we have full equilibrium; otherwise, translational symmetry gets broken as well) nonzero value which points in a certain direction. The residual rotational symmetries which leaves the orientation of this vector invariant remain unbroken but the other rotations get spontaneously broken.

- The laws describing a solid are invariant under the full Euclidean group, but the solid itself spontaneously breaks this group down to a space group. The displacement and the orientation are the order parameters.

- The laws of physics are spatially invariant, but here on the surface of the Earth, we have a background gravitational field (which plays the role of the order parameter here) which points downwards, breaking the full rotational symmetry. This explains why up, down and the horizontal directions are all "different" but all the horizontal directions are still isotropic.

- General relativity has a Lorentz gauge symmetry, but in FRW cosmological models, the mean 4-velocity field defined by averaging over the velocities of the galaxies (the galaxies act like gas particles at cosmological scales) acts as an order parameter breaking this Lorentz symmetry. Similar comments can be made about the cosmic microwave background.

- Here on Earth, Galilean invariance (in the nonrelativistic approximation) is broken by the velocity field of the Earth/atmosphere, which acts as the order parameter here. This explains why people thought moving bodies tend towards rest before Galileo. We tend not to be aware of broken symmetries.

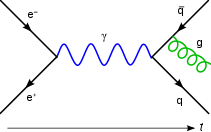

- For the electroweak model, as explained earlier, the Higgs field acts as the order parameter breaking the electroweak gauge symmetry to the electromagnetic gauge symmetry. Like the ferromagnetic example, there is a phase transition at the electroweak temperature. The same comment about us not tending to notice broken symmetries explains why it took so long for us to discover electroweak unification.

- For superconductors, there is a collective condensed matter field ψ which acts as the order parameter breaking the electromagnetic gauge symmetry.

- In general relativity, diffeomorphism covariance is broken by the nonzero order parameter, the metric tensor field.

- Take a flat plastic ruler which is identical on both sides and push both ends together. Before buckling, the system is symmetric under the reflection about the plane of the ruler. But after buckling, it either buckles upwards or downwards.

- Consider a uniform layer of fluid over an infinite horizontal plane. This system has all the symmetries of the Euclidean plane. But now heat the bottom surface uniformly so that it becomes much hotter than the upper surface. When the temperature gradient becomes large enough, convection cells will form, breaking the Euclidean symmetry.

- Consider a bead on a circular hoop that is rotated about a vertical diameter. As the rotational velocity is increased gradually from rest, the bead will initially stay at its initial equilibrium point at the bottom of the hoop (intuitively stable, lowest gravitational potential). At a certain critical rotational velocity, this point will become unstable and the bead will jump to one of two other newly created equilibria, equidistant from the center. Initially, the system is symmetric with respect to the diameter, yet after passing the critical velocity, the bead must choose between the two new equilibrium points, thus breaking symmetry. Note: This can easily be tried at home with an electric drill, a marble, and a pot cover, (or any other combination you can think of) and is the two-dimensional, mechanical analogue of the symmetry breaking that occurs in the Higgs Boson field.

See also

- Dynamical symmetry breaking

- Mermin-Wagner theorem

- Catastrophe theory

- Vacuum fluctuation

- Second-order phase transition

- Goldstone boson

- Electroweak

- Grand unified theory

- Explicit symmetry breaking

External links

| Quantum field theory |

|---|

|

| History |