The Turin Horse

| The Turin Horse | |

|---|---|

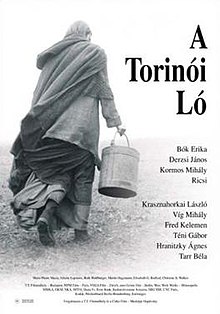

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Béla Tarr Ágnes Hranitzky |

| Written by | László Krasznahorkai Béla Tarr |

| Produced by | Gábor Téni |

| Starring | János Derzsi Erika Bók Mihály Kormos |

| Narrated by | Mihály Ráday |

| Cinematography | Fred Kelemen |

| Edited by | Ágnes Hranitzky |

| Music by | Mihály Víg |

Production company | T. T. Filmműhely |

| Distributed by | Másképp Alapítvány Cirko Film |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 156 minutes |

| Country | Hungary |

| Language | Hungarian |

| Budget | 430 million HUF[1] |

The Turin Horse (Hungarian: A torinói ló) is a 2011 Hungarian period drama film directed by Béla Tarr and Ágnes Hranitzky, starring János Derzsi, Erika Bók and Mihály Kormos.[2] It was co-written by Tarr and his frequent collaborator László Krasznahorkai. It recalls the whipping of a horse in the Italian city of Turin that is rumoured to have caused the mental breakdown of philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche. The film is in black-and-white, shot in only 30 long takes by Tarr's regular cameraman Fred Kelemen,[3] and depicts the repetitive daily lives of the horse-owner and his daughter.

The film was an international co-production led by the Hungarian company T. T. Filmműhely. Tarr announced then that it was to be his last film. After having been postponed several times, it premiered in 2011 at the 61st Berlin International Film Festival, where it received the Jury Grand Prix. The Hungarian release was postponed after the director criticised the country's government in an interview.

The Turin Horse opened to general acclaim from film critics.

Plot

[edit]The film begins with a likely apocryphal story about German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche's mental breakdown on 3 January 1889 when he stayed at number six, Via Carlo Alberto, Turin, Italy. There, a coach driver was having trouble with a stubborn horse. The horse refused to move, whereupon the driver lost his temper and took his whip to it. Nietzsche was greatly disturbed and threw his arms around the horse's neck, sobbing. His neighbor took him home, where he lay motionless and silent for two days on a divan, until he muttered the words "Mutter, ich bin dumm" (Mother, I am stupid). He lived for another ten years, gentle and demented, in the care of his mother and sisters.

The film then moves to the countryside, possibly in the 19th century Great Hungarian Plain, where the coach driver lives with his daughter and the horse. (The narrator hinted that this is the same horse and coach driver seen by Nietzsche, even though the landscape could not be more removed from the neighborhood of Turin.) It depicts six days of their lives. Outside of their hut, windstorms rage. They live out an arduous and repetitive existence and often take turns sitting by the window alone. Starting on the second day, the horse becomes increasingly uncooperative, refusing to leave the property or eat and drink. In the evening a neighbor Bernhard visits to buy some brandy; he claims that the nearby town has been completely destroyed, and blames the apocalyptic scenario on both God and man.

On the third day, a band of "gypsies" (Romani) arrives on a horse-drawn vehicle and drinks from the family's well without permission. The daughter and then the father come out to drive them away. Before departing, some young men from the band warn that they will come back to use the well, and an old man gives the daughter a book, which she reads that evening. When they wake up the next morning on the fourth day, they find that the well is completely dry. The father decides they must abandon the farm; the two pack and depart with a pushcart. The horse does not draw the cart but behaves uncharacteristically well. At some point during their journey, they turn back for unspecified reasons and unpack. On the fifth day, they find the horse is unwell (perhaps dying) and not fit to work. The father removes the horse's reins and leaves it in the barn. The father and daughter then stay indoors for the day, with the wind continuing howling outside. At night, the light which has been working suddenly fails and the house plunges into complete darkness. On the sixth day, we no longer hear the howling winds or see the sun light. Now subsisting on raw potatoes, the daughter refuses to eat or talk, seemingly resigning to her fate. The father appears to follow, not finishing his potato and sitting with his daughter in silence.

Cast

[edit]- János Derzsi as Ohlsdorger (the father)

- Erika Bók as Ohlsdorger's daughter

- Mihály Kormos as Bernhard (the neighbor)

- Mihály Ráday as narrator

Themes

[edit]Director Béla Tarr says that the film is about the "heaviness of human existence". The focus is not on mortality, but rather the daily life: "We just wanted to see how difficult and terrible it is when every day you have to go to the well and bring the water, in summer, in winter... All the time. The daily repetition of the same routine makes it possible to show that something is wrong with their world. It's very simple and pure."[4] Tarr has also described The Turin Horse as the last step in a development throughout his career: "In my first film I started from my social sensibility and I just wanted to change the world. Then I had to understand that problems are more complicated. Now I can just say it’s quite heavy and I don’t know what is coming, but I can see something that is very close – the end."[4]

According to Tarr, the book the daughter receives is an "anti-Bible". The text was an original work by the film's writer, László Krasznahorkai, and contains references to Nietzsche. Tarr described the visitor in the film as "a sort of Nietzschean shadow". As Tarr elaborated, the man differs from Nietzsche in that he is not claiming that God is dead, but rather puts blame on both humans and God: "The key point is that the humanity, all of us, including me, are responsible for destruction of the world. But there is also a force above human at work – the gale blowing throughout the film – that is also destroying the world. So both humanity and a higher force are destroying the world."[4]

Production

[edit]Background

[edit]The idea for the film had its origin in the mid 1980s, when Tarr heard Krasznahorkai retell the story of Nietzsche's breakdown, and ended it by asking what happened to the horse. Tarr and Krasznahorkai then wrote a short synopsis for such a story in 1990, but put it away in favour of making Sátántangó. Krasznahorkai eventually wrote The Turin Horse in prose text after the production of the duo's previous film, the troublesome The Man from London. The Turin Horse never had a conventional screenplay, and Krasznahorkai's prose was what the filmmakers used to find financial partners.[4]

The Turin Horse was produced by Tarr's Hungarian company T. T. Filmműhely, in collaboration with Switzerland's Vega Film Production, Germany's Zero Fiction Film and France's MPM Film. It also had American involvement through the Minneapolis-based company Werc Werk Works. The project received 240,000 euro from Eurimages and 100,000 euro from Medienboard Berlin-Brandenburg.[5]

Filming

[edit]Filming was located to a valley in Hungary. The house, well and stable were all built specifically for the film, and were not artificial sets but proper structures of stone and wood.[4] The supposed 35-day shoot was set to take place during the months of November and December 2008.[6] However because of adverse weather conditions, principal photography was not finished until 2010.[7]

Release

[edit]Tarr announced at the premiere of The Man from London that he was retiring from filmmaking and that his upcoming project would be his last.[5] The Turin Horse was originally planned to be finished in April 2009 and ready to be screened at the 2009 Cannes Film Festival.[5] After several delays, it was finally announced as a competition title at the 61st Berlin International Film Festival, where it premiered on 15 February 2011.[needs update][8]

The Turin Horse was originally set to be released in Hungary on 10 March 2011 through the distributor Mokep.[9] However, in an interview with the German newspaper Der Tagesspiegel on 20 February, Tarr accused the Hungarian government of obstructing artists and intellectuals, in what he referred to as a "culture war" led by the cabinet of Viktor Orbán. As a consequence to these comments, Mokep cancelled its release of the film.[10] It eventually premiered in Hungary on 31 March 2011 instead. It was distributed in five prints through a collaboration between Cirko Film and Másképp Alapítvány.[11]

Home media

[edit]The film was released on DVD and Blu-ray through The Cinema Guild on 17 July 2012.

Reception

[edit]Critical response

[edit]The Turin Horse received critical acclaim. At Metacritic, the film received an average score of 80/100, based on 15 reviews.[12] The film holds an 89% rating on the review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes based on 63 reviews, with an average rating of 8.10/10. The critical consensus states, "Uncompromisingly bold and hauntingly beautiful, Bela Tarr's bleak parable tells a simple story with weighty conviction."[13]

Mark Jenkins of NPR described the film as "... an absolute vision, masterly and enveloping in a way that less personal, more conventional movies are not".[14] A. O. Scott of The New York Times lavished the film with praise, concluding, "The rigors of life can grind you down. The rigor of art can have the opposite effect, and The Turin Horse is an example — an exceedingly rare one in contemporary cinema — of how a work that seems built on the denial of pleasure can, through formal discipline, passionate integrity and terrifying seriousness, produce an experience of exaltation. The movie is too beautiful to be described as an ordeal, but it is sufficiently intense and unyielding that when it is over, you may feel, along with awe, a measure of relief. Which may sound like a reason to stay away, but is exactly the opposite."[15]

Ray Bennett of The Hollywood Reporter wrote from the Berlinale: "Fans of Tarr’s somber and sedate films will know what they are in for and will no doubt find the time well spent. Others might soon grow weary of measured pace of the characters as they dress in their ragged clothes, eat boiled potatoes with their fingers, fetch water, clean their bowls, chop wood and feed the horse." Bennett complimented the cinematography, but added: "That does not, however, make up for the almost complete lack of information about the two characters, and so it is easy to become indifferent to their fate, whatever it is."[16] Variety's Peter Debruge also noted how the narrative provided "little to cling to", but wrote: "Like Hiroshi Teshigahara's life-changingly profound The Woman in the Dunes ... by way of Bresson, Tarr's tale seems to depict the meaning of life in a microcosm, though its intentions are far more oblique. ... As the premise itself concerns the many stories not being told (Nietzsche is nowhere to be found, for instance), it's impossible to keep the mind from drifting to all the other narratives unfolding beyond the film's sparse horizon."[17]

Accolades

[edit]The film won the Jury Grand Prix Silver Bear and the Competition FIPRESCI Prize at the Berlin Film Festival.[18] It was selected as the Hungarian entry for the Best Foreign Language Film at the 84th Academy Awards,[19][20] but it did not make the final shortlist.[21] Tiny Mix Tapes named it the best film of 2012.[22]

In BBC's 2016 poll of the greatest films since 2000, The Turin Horse ranked sixty-third.[23]

See also

[edit]- List of black-and-white films produced since 1970

- List of submissions to the 84th Academy Awards for Best Foreign Language Film

- List of Hungarian submissions for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film

References

[edit]- ^ KATI, GŐZSY. "Tarr Béla utolsó világ premierjére készül". index.hu (in Hungarian). Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- ^ Smith, Ian Hayden (2012). International Film Guide 2012. p. 135. ISBN 978-1908215017.

- ^ The Turin Horse, by Jonathan Romney, Screen Daily, 15 February 2011

- ^ a b c d e Petkovic, Vladan (4 March 2011). "Interview with Béla Tarr". Cineuropa. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- ^ a b c Kriston, Laszlo (26 November 2008). "Bela Tarr preps swan song". Film New Europe. Retrieved 16 December 2010.

- ^ Lemercier, Fabien (21 October 2008). "Tarr inspired by Nietzsche for The Turin Horse". Cineuropa. Retrieved 16 December 2010.

- ^ Lemercier, Fabien (29 March 2010). "Kocsis, Mundruczo and Tarr set sights on the Croisette". Cineuropa. Retrieved 16 December 2010.

- ^ "A torinói ló". berlinale.de. Berlin International Film Festival. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (23 February 2011). "The Turin Horse Sells in 23 Countries". Film New Europe. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ Schulz-Ojala, Jan (7 March 2011). "Schweigen ist Gold". Der Tagesspiegel (in German). Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- ^ MTI (16 March 2011). "Március végén a mozikba kerül A torinói ló". Heti Világgazdaság (in Hungarian). Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ "The Turin Horse Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- ^ "The Turin Horse (2012)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- ^ Jenkins, Mark (9 February 2012). "'The Turin Horse': The Abyss Gazes Implacably Back". NPR. Retrieved 28 August 2014.

- ^ Scott, A. O. (9 February 2012). "Facing the Abyss With Boiled Potatoes and Plum Brandy: Bela Tarr's Final Film, 'The Turin Horse'". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 August 2014.

- ^ Bennett, Ray (15 February 2011). "Turin's Horse: Berlin Review". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 15 February 2011.

- ^ Debruge, Peter (15 February 2011). "The Turin Horse". Variety. Retrieved 16 February 2011.

- ^ "The Awards / Die Preise" (PDF). Berlinale.de. Berlin International Film Festival. 19 February 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 November 2011. Retrieved 20 February 2011.

- ^ Kozlov, Vladimir (1 September 2011). "'The Turin Horse' Announced as Hungary's Oscar Entry". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ "63 Countries Vie for 2011 Foreign Language Film Oscar". oscars.org. Retrieved 14 October 2011.

- ^ "9 Foreign Language Films Vie for Oscar". Retrieved 19 January 2012.

- ^ TMT STAFF. "2012: Favorite 30 Films of 2012". Tiny Mix Tapes.

- ^ "The 21st century's 100 greatest films". BBC. 23 August 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2017.

External links

[edit]- The Turin Horse at IMDb

- The Turin Horse at AllMovie

- The Turin Horse at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Turin Horse at Metacritic

- The Turin Horse at Box Office Mojo

- The Thinking Image: Fred Kelemen on Béla Tarr and The Turin Horse, an interview by Robert Koehler for Cinema Scope

- 2011 films

- 2011 drama films

- Hungarian drama films

- Films set in the 19th century

- Films shot in Hungary

- Films about Friedrich Nietzsche

- Films directed by Béla Tarr

- Hungarian black-and-white films

- 2010s Hungarian-language films

- Films with screenplays by László Krasznahorkai

- Silver Bear Grand Jury Prize winners

- Films scored by Mihály Víg