Two Thousand Maniacs!

| Two Thousand Maniacs! | |

|---|---|

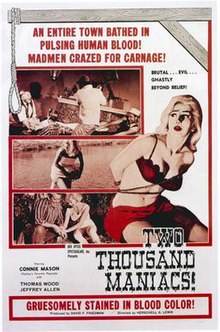

Film poster | |

| Directed by | Herschell Gordon Lewis |

| Written by | Herschell Gordon Lewis[1] |

| Produced by | David F. Friedman[1] |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Herschell Gordon Lewis[1] |

| Edited by | Robert Sinise[1] |

| Music by | Herschell Gordon Lewis[1] |

Production company | David F. Friedman-Herschell G. Lewis Production[1] |

| Distributed by | Box Office Spectaculars[1] |

Release date |

|

Running time | 88 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States[1] |

Two Thousand Maniacs! is a 1964 American horror film[1] written and directed by Herschell Gordon Lewis and starring 1963 Playboy Playmate Connie Mason. It follows a group of Northern tourists who are savagely tortured and murdered during a Confederate celebration of a small Southern community's centennial.

The film has been noted by critics as an early example of hicksploitation in exploitation films, as well as for its sensationalizing of national perceptions between the North and South. The film was remade in 2005 as 2001 Maniacs. The story of the film was inspired by the 1947 Lerner and Loewe musical Brigadoon.[2]

Plot

[edit]In 1965, two rednecks named Rufus and Lester use detour signs to lure six young tourists into their rural town of Pleasant Valley, Georgia. Upon their arrival, they are warmly welcomed by the townsfolk, and are introduced to some of them, including Rufus, Lester, and town mayor Earl Buckman. The tourists are invited to be "guests of honor" for their centennial celebration being held over the weekend. The mayor promises to provide the tourists complimentary hotel rooms, free food and entertainment throughout the celebration, and the visitors decide to go along with it.

That night, while one of the tourists, Bea Miller, is alone in her hotel room, she gets a call from local store owner Harper, who invites her to take a walk with him. She accepts the invitation and he leads her into the woods nearby, where he suddenly takes out a knife and cuts off one of her fingers. Bea is then accosted by Buckman, Rufus, and Lester. As the other three hold her down, Rufus hacks off her arm with an axe, killing her.

Meanwhile, two other tourists, Tom White and his girlfriend Terry Adams, have growing suspicions about the town. During a barbecue later that night (where, unbeknownst to the tourists, Bea's arm is being slowly spit-roasted), Tom quietly leads Terry away to a plaque he found in the woods, which states that a group of renegade Union soldiers massacred much of the Pleasant Valley townsfolk near the end of the Civil War in 1865. They realize that this "centennial" is really an act of revenge for the destruction of the town one hundred years ago, and that they and the other tourists are the intended victims. Buckman, Rufus, and Lester spot Tom and Terry and chase after them, but the couple manages to escape.

Meanwhile, back at the festivities, Harper's girlfriend Betsy gets Bea's husband John drunk on moonshine while the final two tourists, David and Beverly Wells, secretly watch. After Harper escorts the couple back to the hotel, the townspeople surround John and tie both his arms and legs to four horses that are sent running in different directions, dismembering him.

The next morning, Betsy takes David to a gathering on a hill near the lake. Rufus and another man force David into a barrel, which Mayor Buckman hammers nails into before rolling it down the hill, killing David. Later, Lester brings Beverly to the town square to be the judge for the next event; a dunk tank-esque attraction, but one which has a boulder instead of a water tank. Beverly is forcibly tied down to the platform and the crowd take turns throwing rocks at the target, before Lester eventually manages to hit the target, releasing the boulder and causing it to crush Beverly to death.

Meanwhile, Tom and Terry attempt to sneak out of the hotel, but Harper sees them and gives chase. They run through a nearby swamp, where Harper gets stuck in a pool of quicksand and apparently sinks to his death. Eventually, Tom and Terry manage to locate their car and escape the town, as Mayor Buckman deems the centennial a success, and declares the celebration over.

Tom and Terry make it to a police station and tell the sheriff about what happened. The couple returns to Pleasant Valley with the police chief, only to find that the town has mysteriously vanished. The chief becomes skeptical of their claims, but then recalls a local rumor, which claims that the vengeful spirits of those killed in the 1865 massacre still haunt the area where the town once stood. The film ends with the ghosts of Rufus, Lester and Harper heading towards the woods and disappearing, while looking forward to the next centennial hosted in 2065.

Cast

[edit]- William Kerwin (credited as Thomas Wood) as Tom White

- Connie Mason as Terry Adams

- Taalkeus Blank (credited as Jeffrey Allen) as Mayor Buckman

- Ben Moore as Lester MacDonald

- Gary Bakeman as Rufus Tate

- Jerome Eden as John Miller

- Shelby Livingston as Bea Miller

- Michael Korb as David Wells

- Yvonne Gilbert as Beverly Wells

- Stanley Dyrector (credited as Mark Douglas) as Harper Alexander

- Linda Cochran as Betsy

- Vincent Santo as Billy

- Andy Wilson as the Policeman

- The Pleasant Valley Boys

Production

[edit]Two Thousand Maniacs! was filmed in 15 days, early in 1964, in the town of St. Cloud, Florida. According to a contemporary report, the entire town participated in the film.[3][4]

The film was the feature film debut of a nonprofessional Illinois stage actor named Taalkeus Blank (1910-1991; nicknamed "Talky" his entire life) who played Pleasant Valley Mayor Buckman. He used the pseudonym "Jeffery Allen" in all of his film appearances because he was never a member of the Screen Actors Guild. Director Lewis was so impressed by Blank's ability to perfectly mimic any type of Southern accent that he hired Blank to appear in many of his later films, among them Moonshine Mountain (1964), This Stuff'll Kill Ya! (1971) and Year of the Yahoo! (1972), playing various Southern-accented characters under the Jeffrey Allen pseudonym.

The film's budget was considerably larger than what the filmmakers had previously had to work with, and afforded the film a more polished production.[5]

Release

[edit]Two Thousand Maniacs! was heavily cut by the MPAA before its release, which resulted in the film being scantily screened across the country.[5] The film mostly played at drive-in theaters, especially in the Southern United States, where it did considerably well.[5] Among its earliest releases was on October 1, 1964, in Denver, Colorado.[1]

Critical reception

[edit]On review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, Two Thousand Maniacs! holds an approval rating of 41%, based on 22 reviews, and an average rating of 4.33/10. Its consensus reads, "It didn't take much to thrill early splatter fans, and Two Thousand Maniacs! proves it with its shrill soundtrack, basement-level theatrics, and goofy flesh-tearing gore."[6]

Allmovie wrote, "drive-in gore king Herschell Gordon Lewis reached a creative peak with this darkly comic slaughterfest".[7] In a retrospective, Marjorie Baumgarten of the Austin Chronicle called the film "remarkably durable" and referred to it as "one of the sickest movies ever made."[8]

Critical analysis

[edit]Two Thousand Maniacs! was one of the early films to introduce audiences to the formulaic plot of Southern gore films: Northern outsiders who are stranded in the rural South are horrifically murdered by virulent, backwoods Southerners.[9] This subgenre of exploitation peaked with the release of Tobe Hooper's The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974), and Two Thousand Maniacs! has been credited as being influential on Hooper's film.[10]

During the Civil Rights Movement in the United States, television and mainstream narrative films used the "rednecks" caricature rather than a realistic depiction of white Southerners like the televised news of the era.[9] However, Lewis' plotline in Two Thousand Maniacs! focused on the ghosts of a violent, vengeful Confederacy, and acknowledged the region's violent history and place in the anxiety of the rest of the United States.[11][12] The film has been noted by scholars as sensationalizing historical anxieties that the rest of the nation held toward the South's history (and that of its white inhabitants) of extra-legal violence, perceived primitivism, and unresolved regional conflict.[11]

In his essay "Remapping Southern Hospitality", Anthony Szczesiul explained the film's use of Southern hospitality and other Southern stereotypes: "The film's ironic parody of southern hospitality highlights the performative nature of the discourse. When Mayor Buckman delivers his promise of southern hospitality in his thick, cartoonish accent, the reference is immediately recognizable to all–the characters in the film, its actors and director, its original audience, and by us today–but here the possibility of southern hospitality is transformed into a cruel joke: the visitor becomes victim.[11]

Legacy

[edit]"An all-time great because of all the sadism", enthused Cramps singer and horror aficionado Lux Interior. "The people who act in the movie actually live in the town where it was filmed—they look very inbred. There's a wonderful scene where they take this sexy girl and drop this 2,000lb. rock on her from 20 feet, and the whole town's out there watching. Old ladies all looking, like, 'What are we doing here?'"[13]

In popular culture

[edit]The 1980s alternative rock band 10,000 Maniacs took their name in homage to the film as a way of making them stand out from other bands on the college rock scene.[14] The John Waters film Multiple Maniacs is named in homage to the film, as well.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "2,000 Maniacs!". American Film Institute. Archived from the original on August 31, 2022. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- ^ Doll & Morrow 2007, p. 163.

- ^ Romer 2000, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Morgenstern, Meg (January 19, 1964). "When Pleasant Valley Came To St. Cloud". Orlando Sentinel. Orlando, Florida. p. 20F.

- ^ a b c Quarles, Mike (2010). Down and Dirty: Hollywood's Exploitation Filmmakers and Their Movies. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. pp. 169–170. ISBN 978-0786411429. Archived from the original on 2023-08-31. Retrieved 2020-10-11.

- ^ "Two Thousand Maniacs! (1964) – Rotten Tomatoes". Rotten Tomatoes.com. Fandango Media. Archived from the original on 7 April 2019. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- ^ Binion, Cavett. "Two Thousand Maniacs! (1964)". Allmovie. Archived from the original on 31 July 2012. Retrieved 1 July 2012.

- ^ Baumgarter, Marjorie (February 12, 2002). "2000 Maniacs! - Film Calendar". Austin Chronicle. Archived from the original on May 18, 2015. Retrieved May 10, 2015.

- ^ a b Graham, Allison (2001). Framing the South: Hollywood, Television, and Race during the Civil Rights Struggle. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins UP. pp. 168–169. ISBN 0-8018-7445-9.

- ^ Peary, Danny (2014). Cult Horror Movies: Discover the 33 Best Scary, Suspenseful, Gory, and Monstrous Cinema Classics. New York City: Workman Publishing Company. ISBN 9780761181705. Archived from the original on 2023-08-31. Retrieved 2020-10-11.

- ^ a b c Szczesiul, Anthony (August 2007). "Re-mapping Southern Hospitality: Discourse, Ethics, Politics". European Journal of American Culture. 26 (2). Bristol, England: Intellect Books: 132–133. doi:10.1386/ejac.26.2.127_1.

- ^ Cloke, Paul; Little, Jo, eds. (1996). Contested Countryside Cultures: Rurality and Socio-cultural Marginalisation. Abingdon, England: Routledge. ISBN 978-0415140751.

- ^ Mörat (20 September 1997). "Splattermania!". Kerrang!. p. 54.

- ^ Robinson, Joe (October 22, 2012). "'Two Thousand Maniacs!' – 10 Horror Movies That Inspired Band Names". Diffuser. Archived from the original on June 14, 2015. Retrieved June 12, 2015.

Notes

[edit]- Doll, Susan; Morrow, David (2007). Florida on Film: The Essential Guide to Sunshine State Cinema & Locations. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida. ISBN 978-0-8130-3045-6.

- Graham, Alison (2001). Framing the South: Hollywood, Television, and Race during the Civil Rights Struggle. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP. ISBN 0-8018-7445-9.

- Romer, Jean-Claude (2000). "A Bloody New Wave in the United States (July 1964)". Horror Film Reader. New York: Limelight Editions. ISBN 0-87910-297-7.

- Szczesiul, Anthony. "Re-mapping Southern Hospitality: Discourse, Ethics, Politics". European Journal of American Culture 26.2 (2007). pg.132.

External links

[edit]- 1964 films

- 1964 horror films

- 1960s American films

- 1960s English-language films

- 1960s exploitation films

- 1960s slasher films

- American Civil War films

- American exploitation films

- American films about revenge

- American ghost films

- American slasher films

- American splatter films

- Films directed by Herschell Gordon Lewis

- Films set in 1965

- Films set in Florida

- Films shot in Florida

- Southern Gothic films

- Films about mass murder

- Supernatural slasher films

- Films about vacationing

- American supernatural horror films

- Films about torture

- English-language horror films