Hermetica: Difference between revisions

Oops Tag: speedy deletion template removed |

Updated the lead and completely rewrote of the rest of the article |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{short description|Philosophical texts attributed to Hermes Trismegistus}} |

{{short description|Philosophical texts attributed to Hermes Trismegistus}} |

||

{{About|the texts attributed to Hermes Trismegistus|the Argentine heavy metal band|Hermética}} |

{{About|the texts attributed to Hermes Trismegistus|the Argentine heavy metal band|Hermética}} |

||

{{italic title}} |

{{italic title}} |

||

{{Hermeticism}} |

|||

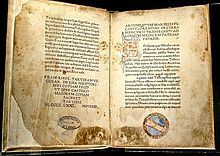

[[File:Corpus Hermeticum.jpg|thumb|''Corpus Hermeticum'': first Latin edition, by [[Marsilio Ficino]], 1471 AD, an edition which belonged formerly to the [[Bibliotheca Philosophica Hermetica]], [[Amsterdam]].]] |

|||

The '''''Hermetica''''' are the philosophical texts attributed to the legendary [[Hellenistic]] figure [[Hermes Trismegistus]] (a [[Syncretism|syncretic combination]] of the Greek god [[Hermes]] and the Egyptian god [[Thoth]]).<ref>A survey of the literary and archaeological evidence for the background of Hermes Trismegistus in the Greek Hermes and the Egyptian Thoth is found in Bull, Christian H. 2018. ''The Tradition of Hermes Trismegistus: The Egyptian Priestly Figure as a Teacher of Hellenized Wisdom''. Leiden: Brill, pp. 33-96.</ref> These texts may vary widely in content and purpose, but are usually subdivided into two main categories: |

|||

* The so-called 'technical' ''Hermetica'': this category contains treatises dealing with [[History of astrology|astrology]], [[History of pharmacy|medicine and pharmacology]], [[alchemy]], and [[magic (supernatural)|magic]], the oldest of which were written in [[Ancient Greek|Greek]] and may go back as far as to the second or third century BCE.<ref>Copenhaver, Brian P. 1992. ''Hermetica: The Greek Corpus Hermeticum and the Latin Asclepius in a New English Translation, with Notes and Introduction''. Cambridge University Press, p. xxxiii; Bull 2018, pp. 2-3. Garth Fowden (1986. ''The Egyptian Hermes: A Historical Approach to the Late Pagan Mind''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 3, note 11) is somewhat more cautious, noting that our earliest testimonies date to the first century BCE.</ref> Many of the texts belonging to this category were later translated into [[Arabic]] and [[Latin]], often being extensively revised and expanded throughout the centuries. Some of them were also originally written in Arabic, though in many cases their status as an original work or translation remains unclear.<ref>Van Bladel, Kevin 2009. ''The Arabic Hermes: From Pagan Sage to Prophet of Science''. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 17.</ref> These Arabic and Latin Hermetic texts were widely copied throughout the [[Middle Ages]] (the most famous example being the '''''[[Emerald Tablet]]'''''). |

|||

The '''''Hermetica''''' are the philosophical texts attributed to the legendary [[Hellenistic]] figure [[Hermes Trismegistus]] (a combination of the Greek god [[Hermes]] and the Egyptian god [[Thoth]]).<ref>A survey of the literary and archaeological evidence for the background of Hermes Trismegistus in the Greek Hermes and the Egyptian Thoth may be found in Bull, Christian H. 2018. ''The Tradition of Hermes Trismegistus: The Egyptian Priestly Figure as a Teacher of Hellenized Wisdom''. Leiden: Brill, pp. 33-96.</ref> These texts may vary widely in content and purpose, but are usually subdivided into two main categories: |

|||

* The so-called 'philosophical' ''Hermetica'': this category contains religio-philosophical treatises which were mostly written in the second and third centuries CE, though the very earliest of them may go back to the first century CE.<ref>Copenhaver 1992, p. xliv; Bull 2018, p. 32. The sole exception to the general dating of c. 100–300 CE is ''[[Definitions of Hermes Trismegistus to Asclepius|The Definitions of Hermes Trismegistus to Asclepius]]'', which may date to the first century CE (see Bull 2018, p. 9, referring to Mahé, Jean-Pierre 1978-1982. ''Hermès en Haute-Egypte''. Vol. I-II. Quebec: Presses de l'Université Laval, vol. 2, p. 278; cf. Mahé, Jean-Pierre 1999. "The Definitions of Hermes Trismegistus to Asclepius" in: Salaman, Clement et al. (eds.). ''The Way of Hermes''. London: Duckworth, pp. 99–122, p. 101). Earlier dates have been suggested, most notably by [[Flinders Petrie]] (500–200 BCE) and Bruno H. Stricker (c. 300 BCE), but these suggestions have been rejected by most other scholars (see Bull 2018, p. 6, note 23).</ref> They are chiefly focused on the relationship between human beings, the cosmos, and God (thus combining philosophical [[philosophical anthropology|anthropology]], [[Cosmology (philosophy)|cosmology]], and [[philosophical theology|theology]]), and on [[Protrepsis and paraenesis|moral exhortations]] calling for a way of life (the so-called 'way of Hermes') leading to spiritual rebirth, and eventually to [[apotheosis]] in the form of a heavenly ascent.<ref>Bull 2018, p. 3.</ref> The treatises in this category were probably all originally written in Greek, even though some of them only survive in [[Coptic language|Coptic]], [[Armenian language|Armenian]], or [[Latin]] translations.<ref>E.g., [[The Discourse on the Eighth and Ninth]] (Coptic; preserved in the [[Nag Hammadi library]], which consists entirely of works translated from Greek into Coptic; see Robinson, James M. 1990. ''The Nag Hammadi Library in English''. 3th, revised edition. New York: HarperCollins, pp. 12-13), the ''[[Definitions of Hermes Trismegistus to Asclepius]]'' (Armenian; see Bull 2018, p. 9), and the ''Asclepius'' (also known as the ''Perfect Discourse'', Latin; see Copenhaver 1992, pp. xliii-xliv).</ref> During the Middle Ages, most of them were only accessible to [[Byzantine]] scholars (an important exception being the '''''Asclepius''''', which mainly survives in an early Latin translation), until a compilation of Greek Hermetic treatises known as the '''''Corpus Hermeticum''''' was translated into Latin by the [[Renaissance]] scholars [[Marsilio Ficino]] (1433–1499) and [[Lodovico Lazzarelli]] (1447–1500).<ref>Copenhaver 1992, pp. xl-xliii; Hanegraaff, Wouter J. 2006. "Lazzarelli, Lodovico" in: Hanegraaff, Wouter J. et al. (eds.). ''Dictionary of Gnosis and Western Esotericism''. Leiden/Boston: Brill, pp. 679-683, p. 680.</ref> |

|||

Though strongly influenced by Greek and Hellenistic philosophy (especially [[Middle Platonism|Platonism]] and [[Stoicism]]),<ref>Bull 2018, p. 2.</ref> and to a lesser extent also by [[Hellenistic Judaism|Jewish]] ideas,<ref>See, e.g., Pearson, Birger 1981. “Jewish Elements in Corpus Hermeticum I (Poimandres)” in: Van den Broek, Roelof and Vermaseren, Maarten J. (eds.). ''Studies in Gnosticism and Hellenistic Religions presented to Gilles Quispel on the Occasion of his Sixty-Fifth Birthday''. Leiden: Brill, pp. 336-348, and the copious references in Bull 2018, p. 29, note 118.</ref> many of the early Greek Hermetic treatises do contain distinctly Egyptian elements, most notably in their affinity with the traditional Egyptian [[wisdom literature]].<ref>Mahé, Jean-Pierre 1978-1982. ''Hermès en Haute-Egypte''. Vol. I-II. Quebec: Presses de l'Université Laval. Mahé also demonstrated numerous other Egyptian influences on the ''Hermetica'' (cf. Bull 2018, pp. 9-10).</ref> This used to be the subject of much doubt,<ref>Following the weighty authority of Festugière, André-Jean 1944-1954. ''La Révélation d'Hermès Trismégiste''. Vol. I-IV. Paris: Gabalda; Festugière, André-Jean 1967. ''Hermétisme et mystique païenne''. Paris: Aubier Montaigne.</ref> but it is now generally admitted that the ''Hermetica'' as such did in fact originate in [[Ptolemaic Kingdom|Hellenistic]] and [[Roman Egypt|Roman]] Egypt,<ref>See Mahé 1978-1982; Fowden 1986; cf. Copenhaver 1992, pp. xlv, lviii.</ref> even if most of the later Hermetic writings (which continued to be composed at least until the twelfth century CE) clearly did not.<ref>For example, the ''Kitāb fi zajr al-nafs'' ("The Book of the Rebuke of the Soul"), the only Arabic Hermetic text that is rather 'religio-philosophical' than 'technical' in nature, is commonly thought to date from the twelfth century; see Van Bladel 2009, p. 226.</ref> It may perhaps even be the case that the great bulk of the early Greek ''Hermetica'' were written by Hellenizing members of the Egyptian priestly class, whose intellectual activity was centred in the environment of the [[Egyptian temples]].<ref>This is the central thesis of Bull 2018; see 12ff.</ref> |

|||

* The so-called 'technical' ''Hermetica'': this first category contains treatises dealing with [[History of astrology|astrology]], [[History of pharmacy|medicine and pharmacology]], [[alchemy]], and [[magic (supernatural)|magic]]. The oldest of these treatises were written in [[Ancient Greek|Greek]], and some of them go back as far as to the first century BCE, or perhaps even to the second or third century BCE.<ref>Bull 2018, pp. 2-3.</ref> On the other hand, an important part of the writings belonging to this category also date from a considerably later period, having been either originally written in [[Arabic]] or surviving only in Arabic translation (sources attested from the eighth century CE and onwards).<ref>Van Bladel, Kevin 2009. ''The Arabic Hermes: From Pagan Sage to Prophet of Science''. Oxford: Oxford University Press.</ref> The most famous among these later Arabic treatises is the '''''[[Emerald Tablet]]'''''. |

|||

* The so-called 'philosophical' ''Hermetica'': this second category contains religio-philosophical treatises taking the form of dialogues between Hermes Trismegistus and his disciples Tat, Asclepius, and Ammon. These were mostly written between c. 100 and c. 300 CE, though the earliest of them may go back to the first century CE, or perhaps even to the first century BCE.<ref>Copenhaver, Brian P. 1992. ''Hermetica: The Greek Corpus Hermeticum and the Latin Asclepius in a New English Translation, with Notes and Introduction''. Cambridge University Press, p. xliv; Bull 2018, p. 32, cf. p. 9. Earlier dates have been suggested, most notably by [[Flinders Petrie]] (500–200 BCE) and Bruno H. Stricker (c. 300 BCE), but these suggestions have been rejected by most other scholars (see Bull 2018, p. 6, note 23).</ref> They are chiefly focused on the relationship between human beings, the cosmos, and God (thus combining philosophical [[philosophical anthropology|anthropology]], [[Cosmology (philosophy)|cosmology]], and [[philosophical theology|theology]]), and on [[Protrepsis and paraenesis|moral exhortations]] in which Hermes calls his pupils to a way of life (the so-called 'way of Hermes') leading to spiritual rebirth, and eventually to [[apotheosis]] in the form of a heavenly ascent.<ref>Bull 2018, p. 3.</ref> The treatises in this category were probably all originally written in Greek, even though some of them only survive in [[Coptic language|Coptic]], [[Armenian language|Armenian]], or [[Latin]] translations.<ref>E.g., [[The Discourse on the Eighth and Ninth]] (Coptic; preserved in the [[Nag Hammadi library]], which consists entirely of works translated from Greek into Coptic; see Robinson, James M. 1990. ''The Nag Hammadi Library in English''. 3th, revised edition. New York: HarperCollins, pp. 12-13), the ''Definitions of Hermes Trismegistus to Asclepius'' (Armenian; see Bull 2018, p. 9), and the ''Asclepius'' (also known as the ''Perfect Discourse'', Latin; see Copenhaver 1992, pp. xliii-xliv).</ref> The most famous among these religio-philosophical ''Hermetica'' are the '''''Corpus Hermeticum''''' (a selection of seventeen treatises first compiled by [[Byzantine]] editors and translated into Latin in the fifteenth century by [[Marsilio Ficino]] and [[Lodovico Lazzarelli]]),<ref>Copenhaver 1992, pp. xl-xliii. Though its individual treatises are cited by other authors from the second and third centuries on, the collection as such is first attested only in the writings of the eleventh century philosopher [[Michael Psellos|Michael Psellus]] (see p. xlii). Ficino only translated the first fourteen treatises (I–XIV), while Lazzarelli translated the remaining three (XVI–XVIII); see Hanegraaff, Wouter J. 2006. "Lazzarelli, Lodovico" in: Hanegraaff, Wouter J. et al. (eds.). ''Dictionary of Gnosis and Western Esotericism''. Leiden/Boston: Brill, pp. 679-683, p. 680. The Chapter no. XV of early modern editions was once filled with an entrance from the [[Suda]] and three excerpts from Hermetic works preserved by [[Stobaeus]], but this chapter was left out in later editions (which contain no chapter XV); see Copenhaver 1992, p. xlix.</ref> the '''''[[Poimandres]]''''' (the opening treatise of the ''Corpus Hermeticum''), the '''''Korē kosmou''''' ("The Daughter of the Cosmos", the longest among the Hermetic excerpts preserved by the fifth century anthologer [[Joannes Stobaeus]]),<ref>Copenhaver 1992, p. xxxviii; cf. Bull 2018, pp. 101-111.</ref> and the '''''Asclepius''''' (a treatise that mainly survives in Latin and that remained available to Latin readers throughout the [[Middle Ages]]).<ref>Copenhaver 1992, pp. xlvii.</ref> |

|||

==The technical ''Hermetica''== |

|||

Though strongly influenced by Greek and Hellenistic philosophy (especially [[Middle Platonism|Platonism]] and [[Stoicism]]),<ref>Bull 2018, p. 2.</ref> and to a lesser extent also by [[Hellenistic Judaism|Jewish]] ideas,<ref>See, e.g., Pearson, Birger 1981. “Jewish Elements in Corpus Hermeticum I (Poimandres)” in: Van den Broek, Roelof and Vermaseren, Maarten J. (eds.). ''Studies in Gnosticism and Hellenistic Religions presented to Gilles Quispel on the Occasion of his Sixty-Fifth Birthday''. Leiden: Brill, pp. 336-348, and the copious references in Bull 2018, p. 29, note 118.</ref> many of the Greek Hermetic treatises do contain distinctly [[Ptolemaic Kingdom|Egyptian]] elements, most notably in their affinity with the traditional Egyptian [[wisdom literature]].<ref>Mahé, Jean-Pierre 1978-1982. ''Hermès en Haute-Egypte''. Vol. I-II. Quebec: Presses de l'Université Laval. Mahé also demonstrated numerous other Egyptian influences on the ''Hermetica'' (cf. Bull 2018, pp. 9-10).</ref> Though this used to be the subject of much doubt,<ref>Following the weighty authority of Festugière, André-Jean 1944-1954. ''La Révélation d'Hermès Trismégiste''. Vol. I-IV. Paris: Gabalda; Festugière, André-Jean 1967. ''Hermétisme et mystique païenne''. Paris: Aubier Montaigne.</ref> it is now generally admitted that the earliest Hermetic treatises did in fact originate in an Egyptian milieu.<ref>See Mahé 1978-1982; Fowden, Garth 1986. ''The Egyptian Hermes: A Historical Approach to the Late Pagan Mind''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; cf. Copenhaver 1992, pp. xlv, lviii.</ref> It may perhaps even be the case that the great bulk of the Greek ''Hermetica'' were written by Hellenizing members of the Egyptian priestly class, whose intellectual activity was centred in the environment of the [[Egyptian temples]].<ref>This is the central thesis of Bull 2018; see 12ff.</ref> |

|||

== |

=== Greek === |

||

{{Hermeticism}} |

|||

One of the most important collections of Hermetic treatises is the so-called ''Corpus Hermeticum''. The name of this collection can be somewhat misleading, since it contains only a very small selection of extant Hermetic texts (whereas the word [https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/corpus#English corpus] is usually reserved for the ''entire'' body of extant writings related to some subject). It originated with [[Marsilio Ficino]]'s Latin translation of fourteen tracts, which appeared in eight [[incunabulum|early printed]] editions before 1500, and in a further twenty-two by 1641.<ref>Noted by [[George Sarton]], review of [[Walter Scott (scholar)|Walter Scott]]'s ''Hermetica'', ''Isis'' '''8'''.2 (May 1926:343-346) p. 345</ref> This collection, which includes ''[[Poimandres]]'' and some addresses of Hermes to disciples Tat, Ammon and Asclepius, was said to have originated in the school of [[Ammonius Saccas]] and to have passed through the keeping of [[Michael Psellus]]: it is preserved in fourteenth century manuscripts.<ref>Anon, ''Hermetica – a new translation'', Pembridge Design Studio Press, 1982</ref> The last three tracts in modern editions were translated independently from another manuscript by Ficino's contemporary [[Lodovico Lazzarelli]] (1447–1500) and first printed in 1507. Extensive quotes of similar material are found in classical authors such as [[Joannes Stobaeus]]. |

|||

==== Greek astrological ''Hermetica'' ==== |

|||

Parts of the ''Hermetica'' appeared in the 2nd-century [[Gnostic]] library found in [[Nag Hammadi]], which consists of [[Coptic language|Coptic]] documents translated from the Greek.<ref>Robinson, James M. 1990. ''The Nag Hammadi Library in English''. 3th, revised edition. New York: HarperCollins, pp. 12-13.</ref> Other works in [[Syriac language|Syriac]], [[Arabic language|Arabic]] and other languages were also attributed to Hermes. |

|||

The oldest known texts associated with [[Hermes Trismegistus]] are a number of [[History of astrology|astrological]] works which may go back as far as to the second or third century BCE: |

|||

For a long time, it was thought that these texts were remnants of an extensive literature, part of the [[syncretism|syncretic]] cultural movement that also included the [[Neoplatonism|Neoplatonists]] of the [[Greco-Roman mysteries]] and late [[Orpheus|Orphic]] and [[Pythagoreanism|Pythagorean]] literature and influenced [[Gnosticism|Gnostic forms]] of the [[Abrahamic religions]]. However, there are significant differences:<ref>[[Roel van den Broek|Broek, Roelof Van Den]]. "Gnosticism and Hermitism in Antiquity: Two Roads to Salvation." In Broek, Roelof Van Den, and Wouter J. Hanegraaff. 1998. ''Gnosis and Hermeticism From Antiquity to Modern Times.'' Albany: State University of New York Press.</ref> the ''Hermetica'' are little concerned with [[Greek mythology]] or the technical minutiae of metaphysical [[Neoplatonism]]. In addition, [[Neoplatonism|Neoplatonic]] philosophers, who quote works of [[Orpheus]], [[Zoroaster]] and [[Pythagoras]], cite [[Hermes Trismegistus]] less often. Still, most of these schools do agree in attributing the creation of the world to a [[Demiurge]] rather than the supreme being<ref>Anon, ''Hermetica – a new translation'', Pembridge Design Studio Press, 1982</ref> and in accepting [[reincarnation]]. |

|||

* The '''''Salmeschoiniaka''''' (the "Wandering of the Influences"), perhaps composed in Alexandria in the second or third century BCE, deals with the configurations of the stars.<ref>Copenhaver 1992, p. xxxiii; Bull 2018, pp. 387-388.</ref> |

|||

Many Christian intellectuals from all eras have written about Hermeticism, both positive and negative.<ref>{{cite book |title=Hermetica |date=1992 |url=https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/hermetica/A2779DE70B173114CC8669BEB3CF507D |language=en |quote=[By order of appearance] Arnobius, Lactantius, Clement of Alexandria, Michael Psellus, Tertullian, Augustine, Lazzarelli, Alexander of Hales, Thomas Aquinas, Bartholomew of England, Albertus Magnus, Thierry of Chartres, Bernardus Silvestris, John of Salisbury, Alain de Lille, Vincent of Beauvais, William of Auvergne, Thomas Bradwardine, Petrarch, Marsilio Ficino, Cosimo de' Medici, Francesco Patrizi, Francesco Giorgi, Agostino Steuco, Giovanni Nesi, Hannibal Rossel, Guy Lefevre de la Boderie, Philippe du Plessis Mornay, Giordano Bruno, Robert Fludd, Michael Maier, Isaac Casaubon, Isaac Newton}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |title=Hermetica |date=1992 |url=https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/hermetica/A2779DE70B173114CC8669BEB3CF507D |language=en |quote=[T]he Suda around the year 1000: "Hermes Trismegistus [...] was an Egyptian wise man who flourished before Pharaoh's time. He was called Trismegistus on account of his praise of the trinity, saying that there is one divine nature in the trinity."}}</ref> However, modern scholars find no traces of Christian influences in the texts.<ref>{{cite book |title=Hermetica, The Greek Corpus Hermeticum and the Latin Asclepius in a New English Translation, with Notes and Introduction |date=1992 |url=https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/hermetica/A2779DE70B173114CC8669BEB3CF507D |language=en |quote=The Teachings of Hermes Trismegistos, which located the roots of Hermetism in Posidonius, the Middle Stoics and Philo, all suitably Hellenic, but detected no Christianity in the Corpus.}}</ref> Although Christian authors have looked for similarities between Hermeticism and Christian scriptures, scholars remain unconvinced.<ref>{{cite book |title=Hermetica |date=1992 |url=https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/hermetica/A2779DE70B173114CC8669BEB3CF507D |language=en |quote=The possibility of influence running from Hermetic texts to Christian scripture has seldom tempted students of the New Testament.}}</ref> |

|||

* The '''Nechepsos-Petosiris texts''' are a number of anonymous works dating to the second century BCE which were falsely attributed to the Egyptian king [[Necho II]] (610–595 BCE, referred to in the texts as Nechepsos) and his legendary priest Petese (referred to in the texts as Petosiris). These texts, only fragments of which survive, ascribe the astrological knowledge they convey to the authority of Hermes.<ref>Bull 2018, pp. 163-174; cf. Copenhaver 1992, p. xxxiii. On the identification of Nechepsos with Necho II and of Petosiris with Petese, see the references in Bull 2018, p. 163, note 295.</ref> |

|||

* The '''''Art of Eudoxus''''' is a treatise on [[astronomy]] which was preserved in a second-century BCE [[papyrus]] and which mentions Hermes as an authority.<ref>Bull 2018, pp. 167-168.</ref> |

|||

* The '''''Liber Hermetis''''' ("The Book of Hermes") is an important work on astrology laying out the names of the [[Decan|decans]] (a distinctly Egyptian system which divided the [[zodiac]] into 36 parts). It survives only in an early (fourth- or fifth-century CE) Latin translation,<ref>Copenhaver 1992, p. xlv.</ref> but contains elements that may be traced to the second or third century BCE.<ref>Copenhaver 1992, p. xxxiii; Bull 2018, pp. 385-386.</ref> |

|||

Other early Greek Hermetic works on astrology include: |

|||

==Middle Ages and Renaissance== |

|||

Although the most famous examples of Hermetic literature were products of [[Greek language|Greek]]-speakers under Roman rule, the genre did not suddenly stop with the fall of the Empire but continued to be produced in [[Coptic language|Coptic]], [[Syriac language|Syriac]], [[Arabic language|Arabic]], [[Armenian language|Armenian]] and [[Byzantine Greek]]. The most famous among these later ''Hermetica'' is the ''[[Emerald Tablet]]'', a [[late antique]] or [[Early Middle Ages|early medieval]] short [[alchemy|alchemical]] text first attested in Arabic sources dating to the late eight or early ninth centuries.<ref>Kraus, Paul 1942-1943. ''Jâbir ibn Hayyân: Contribution à l'histoire des idées scientifiques dans l'Islam. I. Le corpus des écrits jâbiriens. II. Jâbir et la science grecque''. Cairo: Institut français d'archéologie orientale, vol. II, pp. 274-275; Weisser, Ursula 1980. ''Das Buch über das Geheimnis der Schöpfung von Pseudo-Apollonios von Tyana''. Berlin: De Gruyter, p. 54.</ref> Little else of this rich literature is easily accessible to non-specialists. The mostly gnostic [[Nag Hammadi Library]], discovered in 1945, also contained one previously unknown hermetic text called ''[[The Ogdoad and the Ennead]]'', a description of a hermetic initiation into gnosis that has led to new perspectives on the nature of Hermetism as a whole, particularly due to the research of [[Jean-Pierre Mahé]].<ref>Mahé, ''Hermès en Haute Egypte'' 2 vols. (Quebec) 1978, 1982.</ref> |

|||

* The '''''Brontologion''''': a treatise on the various effects of thunder in different months.<ref>Copenhaver 1992, p. xxxiii; Bull 2018, p. 168.</ref> |

|||

Many hermetic texts were not known to the [[Greek East and Latin West|Latin West]] during the [[Middle Ages]], but were discovered in [[Byzantine]] copies and popularized in [[Italy]] during the [[Renaissance]]. The impetus for this revival came from the [[Latin]] translation by [[Marsilio Ficino]], a member of the [[Cosimo de' Medici|de' Medici]] [[court (royal)|court]], who published a collection of thirteen tractates in 1471, as ''De potestate et sapientia Dei''.<ref>Among the treasures of the [[Bibliotheca Philosophica Hermetica]] in Amsterdam is this ''Corpus Hermeticum'' as published in 1471.</ref> The ''Hermetica'' provided a seminal impetus in the development of Renaissance thought and culture, having a profound impact on [[alchemy]] and modern magic as well as influencing philosophers such as [[Giordano Bruno]] and [[Pico della Mirandola]], Ficino's student. This influence continued as late as the 17th century with authors such as Sir [[Thomas Browne]]. |

|||

* The '''''Peri seismōn''''' ("On earthquakes"): a treatise on the relation between earthquakes and astrological signs.<ref>Copenhaver 1992, p. xxxiii.</ref> |

|||

* The '''''Book of Asclepius Called Myriogenesis''''': a treatise on astrological medicine.<ref>Copenhaver 1992, p. xxxiii.</ref> |

|||

* The '''''Holy Book of Hermes to Asclepius''''': a treatise on astrological botany describing the relationships between various plants and the [[decans]].<ref>Copenhaver 1992, p. xxxiv.</ref> |

|||

* The '''''Fifteen Stars, Stones, Plants and Images''''': a treatise on astrological [[History of mineralogy|mineralogy]] and [[History of botany|botany]] dealing with the effect of the stars on the [[History of pharmacy|pharmaceutical]] powers of minerals and plants.<ref>Copenhaver 1992, p. xxxiv.</ref> |

|||

==== Greek alchemical ''Hermetica'' ==== |

|||

==History of modern scholarship== |

|||

During the [[Renaissance]], all texts attributed to Hermes Trismegistus were believed to be of ancient Egyptian origin. In the early seventeenth century, the classical scholar [[Isaac Casaubon]] (1559–1614) demonstrated that some texts betrayed too recent a vocabulary, and must date from the late [[Hellenistic]] or early Christian era at the earliest.<ref>Copenhaver, Brian P. 1992. ''Hermetica: The Greek Corpus Hermeticum and the Latin Asclepius in a New English Translation, with Notes and Introduction''. Cambridge University Press, p. l.</ref> This conclusion was reaffirmed in the early twentieth century by the work of scholars like [[C. H. Dodd]].<ref>In his Dodd, Charles H. 1935. ''The Bible and the Greeks''. London: Hodder & Stoughton; see Copenhaver 1992, pp. l, lvii.</ref> More recent research, while reaffirming the late dating in a period of [[Syncretism|syncretic]] cultural ferment in Roman Egypt, suggests more continuity with the culture of Egypt than had previously been believed.<ref>Fowden, Garth, The Egyptian Hermes : a historical approach to the late pagan mind (Cambridge/New York : Cambridge University Press), 1986</ref> There are many parallels with Egyptian prophecies and hymns to the gods, but the closest comparisons can be found in Egyptian [[wisdom literature]], which is characteristically couched in words of advice from a "father" to a "son".<ref>[[Jean-Pierre Mahé]], "Preliminary Remarks on the Demotic "Book of Thoth" and the Greek Hermetica" ''Vigiliae Christianae'' '''50'''.4 (1996:353-363) p.358f.</ref> [[Demotic (Egyptian)|Demotic]] (late Egyptian) [[Papyrus|papyri]] contain substantial sections of a dialogue of Hermetic type between Thoth and a disciple.<ref>See R. Jasnow and Karl-Th. Zausich, "A Book of Thoth?" (paper given at the 7th International Congress of Egyptologists: Cambridge, 3–9 September 1995).</ref> |

|||

Starting in the first century BCE, a number of Greek works on [[alchemy]] were attributed to Hermes Trismegistus. These are now all lost, except for a number of fragments (one of the larger of which is called '''''Isis the Prophetess to her Son Horus''''') preserved in later alchemical works dating to the second and third centuries CE. Especially important is the use made of them by the Egyptian alchemist [[Zosimos of Panopolis|Zosimus of Panopolis]] (fl. c. 300 CE), who also seems to have been familiar with the religio-philosophical ''Hermetica''.<ref>Copenhaver 1992, p. xxxiv.</ref> Hermes' name would become more firmly associated with alchemy in the medieval Arabic sources (see [[#Arabic alchemical Hermetica|below]]), of which it is not yet clear to what extent they drew on the earlier Greek literature.<ref>Van Bladel 2009, p. 17.</ref> |

|||

==Translations and editions== |

|||

[[John Everard (preacher)|John Everard]]'s historically important 1650 translation into [[English language|English]] of the ''Corpus Hermeticum'', entitled ''The Divine Pymander in XVII books'' (London, 1650) was from Ficino's Latin translation; it is no longer considered reliable by scholars.{{Citation needed|date=April 2020}} The modern standard editions are the Budé edition by A. D. Nock and A.-J. Festugière (Greek and French, 1946, repr. 1991) and Brian P. Copenhaver (English, 1992).<ref>{{cite journal|title=A New Translation of the Hermetica - Brian P. Copenhaver: Hermetica: The Greek Corpus Hermeticum and the Latin Asclepius in a New English Translation, with Notes and Introduction. |author=J. Gwyn Griffiths |periodical=The Classical Review |volume=43 |issue=2 |publisher=[[Cambridge University Press]] |date=October 1993 |url=https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/classical-review/article/new-translation-of-the-hermetica-copenhaver-brian-p-hermetica-the-greek-corpus-hermeticum-and-the-latin-asclepius-in-a-new-english-translation-with-notes-and-introduction-pp-lxxxiii-320-cambridge-cambridge-university-press-1992-45/A53F30836C4E16E6CDD270D135FC83C1 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|title=Brian P. Copenhaver, Hermetica: The Greek Corpus Hermeticum and the Latin Asdepius in a New English Translation with Notes and Introduction. |author=John Monfasani |periodical=The British Journal for the History of Science |volume=26 |issue=4 |publisher=[[Cambridge University Press]] |date=December 1993 |url=https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/british-journal-for-the-history-of-science/article/brian-p-copenhaver-hermetica-the-greek-corpus-hermeticum-and-the-latin-asdepius-in-a-new-english-translation-with-notes-and-introduction-cambridge-cambridge-university-press-1992-pp-lxxxiii-320-isbn-0521361443-4500-6995/7F8F960A233E2E4D1D3526BE2D9EC6C1}}</ref> |

|||

==== Greek magical ''Hermetica'' ==== |

|||

==Contents of ''Corpus Hermeticum''== |

|||

The following are the titles given to the eighteen tracts, as translated by [[G.R.S. Mead]]:<!--Copenhaver's headings would be preferable--> |

|||

: I. [[Poimandres|Pœmandres]], the Shepherd of Men |

|||

: (II.) The General Sermon |

|||

: II. (III.) To Asclepius |

|||

: III. (IV.) The Sacred Sermon |

|||

: IV. (V.) The Cup or Monad |

|||

: V. (VI.) Though Unmanifest God is Most Manifest |

|||

: VI. (VII.) In God Alone is Good and Elsewhere Nowhere |

|||

: VII. (VIII.) The Greatest Ill Among Men is Ignorance of God |

|||

: VIII. (IX.) That No One of Existing Things doth Perish, but Men in Error Speak of Their Changes as Destructions and as Deaths |

|||

: IX. (X.) On Thought and Sense |

|||

: X. (XI.) The Key |

|||

: XI. (XII.) Mind Unto Hermes |

|||

: XII. (XIII.) About the Common Mind |

|||

: XIII. (XIV.) The Secret Sermon on the Mountain |

|||

: XIV. (XV.) A Letter to Asclepius |

|||

: (XVI.) The Definitions of Asclepius unto King Ammon |

|||

: (XVII.) Of Asclepius to the King |

|||

: (XVIII.) The Encomium of Kings |

|||

* The '''''[[Cyranides]]''''' is a work on healing magic which treats of the magical powers and healing properties of [[History of mineralogy|minerals]], [[History of botany|plants]] and [[History of zoology through 1859|animals]], for which it regularly cites Hermes as a source.<ref>Copenhaver 1992, pp. xxxiv-xxxv. The Greek text was edited by Kaimakis, Dimitris 1976. ''Die Kyraniden''. Meisenheim am Glan: Hain. English translation of the first book in Waegeman, Maryse 1986. ''Amulet and Alphabet: Magical Amulets in the First Book of Cyranides''. Amsterdam.</ref> It was independently translated both into Arabic and Latin.<ref>The Arabic translation of the first book was edited by Toral-Niehoff, Isabel 2004. ''Kitab Giranis. Die arabische Übersetzung der ersten Kyranis des Hermes Trismegistos und die griechischen Parallelen''. München: Herbert Utz. The Arabic fragments of the other books were edited by Ullmann, Manfred 2020. “Die arabischen Fragmente der Bücher II bis IV der Kyraniden” in: ''Studia graeco-arabica'', 10, pp. 49-58. The Latin translation was edited by Delatte, Louis 1942. ''Textes latins et vieux français relatifs aux Cyranides''. Paris: Droz.</ref> |

|||

The following are the titles given by [[John Everard (preacher)|John Everard]]: |

|||

* The '''''[[Greek Magical Papyri]]''''' are a modern collection of [[papyrus|papyri]] dating from various periods between the second century BCE and the fifth century CE. They mainly contain practical instructions for spells and incantations, some of which cite Hermes as a source.<ref>Copenhaver 1992, pp. xxxv-xxxvi.</ref> |

|||

# The First Book |

|||

# The Second Book. Called [[Poimandres|Poemander]] |

|||

=== Arabic === |

|||

# The Third Book. Called The Holy Sermon |

|||

# The Fourth Book. Called The Key |

|||

Many [[Arabic]] works attributed to Hermes Trismegistus still exist today, although the great majority of them have not yet been published and studied by modern scholars.<ref>According to Van Bladel 2009, p. 17, note 42, there are least twenty Arabic ''Hermetica'' extant.</ref> For this reason too, it is often not clear to what extent they drew on earlier Greek sources. The following is a very incomplete list of known works: |

|||

# The Fifth Book |

|||

# The Sixth Book. Called That in God Alone Is Good |

|||

==== Arabic astrological ''Hermetica'' ==== |

|||

# The Seventh Book. His Secret Sermon in the Mount of Regeneration, And |

|||

# The Profession of Silence. To His Son Tat |

|||

Some of the earliest attested Arabic Hermetic texts deal with [[History of astrology|astrology]]: |

|||

# The Eighth Book. That the Greatest Evil in Man, Is the Not Knowing God |

|||

# The Ninth Book. A Universal Sermon to Asclepius |

|||

* The '''''Qaḍīb al-dhahab''''' ("The Rod of Gold"), or the '''''Kitāb Hirmis fī taḥwīl sinī l-mawālīd''''' ("The Book of Hermes on the Revolutions of the Years of the Nativities") is an Arabic astrological work translated from [[Middle Persian]] by [[Omar Tiberiades|ʿUmar ibn al-Farrukhān al-Ṭabarī]] (d. 816 CE), who was the court astrologer of the [[Abbasid]] caliph [[al-Mansur]] (r. 754-775).<ref>Van Bladel 2009, p. 28.</ref> |

|||

# The Tenth Book. The Mind to Hermes |

|||

* The '''''Carmen astrologicum''''' is an astrological work originally written by the first century CE astrologer [[Dorotheus of Sidon]]. It is lost in Greek, but survives in an Arabic translation, which was in turn based upon a Middle Persian intermediary. It was also translated by ʿUmar ibn al-Farrukhān al-Ṭabarī. The extant Arabic text refers to two Hermeses, and cites a book of Hermes on the positions of the planets.<ref>Van Bladel 2009, pp. 28-29.</ref> |

|||

# The Eleventh Book. Of the Common Mind to Tat |

|||

* The '''''Kitāb Asrār an-nujūm''''' ("The Book of the Secrets of the Stars", later translated into Latin as the '''''Liber de stellis beibeniis''''') is a treatise describing the influences of the brightest [[fixed stars]] on personal characteristics. The Arabic work was translated from a Middle Persian version which can be shown to date from before c. 500 CE, and which shared a source with the [[Byzantine]] astrologer [[Rhetorius]] (fl. c. 600 CE).<ref>Van Bladel 2009, pp. 27-28. The Arabic text and its Latin translation were edited by Kunitzsch, Paul 2001 (ed.). "Liber de stellis beibeniis" in: Bos, Gerrit and Burnett, Charles and Lucentini, Paolo et al. (eds.). ''Hermetis Trismegisti Astrologica et Divinatoria''. Corpus Christianorum, CXLIV. Hermes Latinus, IV.IV. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 7-81. See also Kunitzsch, Paul 2003. "Origin and History of Liber de stellis beibeniis" in: Lucentini, Paolo et al. (eds.). ''Hermetism from Late Antiquity to Humanism. La tradizione ermetica dal mondo tardo-antico all'umanesimo. Atti del Convegno internazionale di studi, Napoli, 20-24 novembre 2001''. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 449-460.</ref> |

|||

# The Twelfth Book. His Crater or Monas |

|||

* The '''''Kitāb ʿArḍ Miftāḥ al-Nujūm''''' ("The Book of the Exposition of the Key to the Stars") is an Arabic astrological treatise attributed to Hermes which claims to have been translated in 743 CE, but which in reality was probably translated in the circles of [[Abu Ma'shar]] (787–886 CE).<ref>Bausani, Alessandro 1983. “Il Kitāb ʿArḍ Miftāḥ al-Nujūm attribuito a Hermes: Prima traduzione araba di un testo astrologico ?” in: ''Atti della Academia Nazionale dei Lincei, Anno 380, Memorie, Classe di Science morali, storiche e filologiche'', Serie VIII, Volume XXVII, Fasciolo 2; Bausani, Alessandro 1986. “Il Kitāb ʿArḍ Miftāḥ al-Nujūm attribuito a Hermes” in: ''Actas do XI Congresso da UEAI (Evora 1982)''. Evora, 371 ff. On the dating, see Ullmann, Manfred 1994. ''Das Schlangenbuch des Hermes Trismegistos''. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, pp. 7-8.</ref> |

|||

# The Thirteenth Book. Of Sense and Understanding |

|||

# The Fourteenth Book. Of Operation and Sense |

|||

==== [[Alchemy and chemistry in the medieval Islamic world|Arabic alchemical]] ''Hermetica'' ==== |

|||

# The Fifteenth Book. Of Truth to His Son Tat |

|||

# The Sixteenth Book. That None of the Things That Are, Can Perish |

|||

* The '''''Sirr al-khalīqa wa-ṣanʿat al-ṭabīʿa''''' ("The Secret of Creation and the Art of Nature"), also known as the '''''Kitāb al-ʿilal''''' ("The Book of Causes") is an encyclopedic work on natural philosophy falsely attributed to [[Apollonius of Tyana]] (c. 15–100, Arabic: Balīnūs or Balīnās). It was compiled in Arabic in the late eighth or early ninth century,<ref>Kraus, Paul 1942-1943. ''Jâbir ibn Hayyân: Contribution à l'histoire des idées scientifiques dans l'Islam. I. Le corpus des écrits jâbiriens. II. Jâbir et la science grecque''. Cairo: Institut français d'archéologie orientale, vol. II, pp. 274-275 (c. 813–833); Weisser, Ursula 1980. ''Das Buch über das Geheimnis der Schöpfung von Pseudo-Apollonios von Tyana''. Berlin: De Gruyter, p. 54 (c. 750–800).</ref> but was most likely based on (much) older Greek and/or Syriac sources.<ref>Kraus 1942-1943, vol. II, pp. 270–303; Weisser 1980, pp. 52–53.</ref> It contains the earliest known version of the sulfur-mercury theory of metals (according to which all metals are composed of various proportions of [[sulfur]] and [[Mercury (element)|mercury]]),<ref>Kraus 1942−1943, vol. II, p. 1, note 1; Weisser 1980, p. 199.</ref> which lay at the foundation of all theories of metallic composition until the eighteenth century.<ref>Norris, John 2006. [https://doi.org/10.1179/174582306X93183 "The Mineral Exhalation Theory of Metallogenesis in Pre-Modern Mineral Science"] in: ''Ambix'', 53, pp. 43–65.</ref> In the frame story of the ''Sirr al-khalīqa'', Balīnūs tells his readers that he discovered the text in a vault below a statue of Hermes in [[Tyana]], and that, inside the vault, an old corpse on a golden throne held the ''Emerald Tablet''.<ref>Ebeling, Florian 2007. ''The Secret History of Hermes Trismegistus: Hermeticism from Ancient to Modern Times''. Ithaca: Cornell university press, pp. 46-47.</ref> It was translated into Latin by [[Hugo of Santalla]] in the twelfth century.<ref>See Hudry, Françoise 1997-1999. "Le De secretis nature du Ps. Apollonius de Tyane, traduction latine par Hugues de Santalla du Kitæb sirr al-halîqa" in: ''Chrysopoeia'', 6, pp. 1-154.</ref> |

|||

# The Seventeenth Book. To Asclepius, to be Truly Wise |

|||

* The '''''[[Emerald Tablet]]''''': a compact and cryptic text first attested in the ''Sirr al-khalīqa wa-ṣanʿat al-ṭabīʿa'' (late eighth or early ninth century). There are several other, slightly different Arabic versions (among them one quoted by [[Jabir ibn Hayyan]], and one found in the longer version of the pseudo-Aristotelian ''[[Secretum secretorum|Sirr al-asrār]]'' or "Secret of Secrets"), but these all date from a later period.<ref>Weisser 1980, p. 46.</ref> It was translated several times into Latin in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries,<ref>See Hudry 1997-1999, p. 152 (as part of the Latin translation of the ''Sirr al-khalīqa''; English translation in Litwa, M. David 2018. ''Hermetica II: The Excerpts of Stobaeus, Papyrus Fragments, and Ancient Testimonies in an English Translation with Notes and Introductions''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 316); Steele, Robert 1920. ''Secretum secretorum cum glossis et notulis''. Opera hactenus inedita Rogeri Baconi, vol. V. Oxford: Clarendon Press, pp. 115-117 (as part of the Latin translation of the ''Sirr al-asrār''); Steele, Robert and Singer, Dorothea Waley 1928. [https://doi.org/10.1177%2F003591572802100361 “The Emerald Table”] in: ''Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine'', 21, pp. 41–57/485–501 (as part of the Latin translation of the ''Liber dabessi'', a collection of commentaries on the ''Tablet'').</ref> and was widely regarded by medieval and early modern [[alchemy|alchemists]] as the foundation of their art. |

|||

* The '''''Risālat al-Sirr''''' ("The Epistle of the Secret") is an Arabic alchemical treatise probably composed in tenth century [[Fatimid]] Egypt.<ref>Edited by Vereno, Ingolf 1992. ''Studien zum ältesten alchemistischen Schrifttum. Auf der Grundlage zweier erstmals edierter arabischer Hermetica''. Islamkundliche Untersuchungen, band 155. Berlin: Klaus Schwarz Verlag, pp. 136-159.</ref> |

|||

* The '''''Risālat al-Falakiyya al-kubrā''''' ("The Great Treatise of the Spheres") is an Arabic alchemical treatise composed in the tenth or eleventh century. Perhaps inspired by the ''Emerald Tablet'', it describes the author's (Hermes') attainment of secret knowledge through his ascension of the [[Seven Heavens|seven]] heavenly [[Celestial spheres|spheres]].<ref>Van Bladel 2009, pp. 181-183 (cf. p. 171, note 25). Also edited by Vereno 1992, pp. 160-181.</ref> |

|||

* The '''''Kitāb dhakhīrat al-Iskandar''''' ("The Treasure of Alexander"): a work dealing with alchemy, [[talisman]]s, and specific properties, which cites Hermes as its ultimate source.<ref>Ruska, Julius 1926. ''Tabula Smaragdina. Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der hermetischen Literatur''. Heidelberg: Winter, pp. 68-107.</ref> |

|||

* The '''''Liber Hermetis de alchemia''''' ("The Book of Hermes on Alchemy"), also known as the '''''Liber dabessi''''' or the '''''Liber rebis''''' is a collection of commentaries on the ''Emerald Tablet''. Translated from the Arabic, it is only extant in Latin. It is this Latin translation of the ''Emerald Tablet'' on which all later versions are based.<ref>Edited by Steele, Robert and Singer, Dorothea Waley 1928. [https://doi.org/10.1177%2F003591572802100361 “The Emerald Table”] in: ''Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine'', 21, pp. 41–57/485–501.</ref> |

|||

==== Arabic magical ''Hermetica'' ==== |

|||

* The '''''Kitāb al-Isṭamākhīs''''', '''''Kitāb al-Isṭamāṭīs''''', '''''Kitāb al-Usṭuwwaṭās''''', '''''Kitāb al-Madīṭīs''''', and '''''Kitāb al-Hādīṭūs''''', dubbed by Kevin van Bladel the ''Talismanic Pseudo-Aristotelian Hermetica'', are a number of closely related and partially overlapping texts. Purporting to be written by [[Aristotle]] in order to teach his pupil [[Alexander the great]] the secrets of Hermes, they deal with the names and powers of the [[Planetary intelligence|planetary spirits]], the making of [[Talisman|talismans]], and the concept of a personal "perfect nature".<ref>Van Bladel 2009, pp. 101-102, 114, 224. A small fragment from the ''Kitāb al-Isṭamākhīs'' was published by Badawī, ‘Abd al-Raḥmān [1947] 1982. ''al-Insāniyya wa-l-wujūdiyya fī l-fikr al-‘Arabī''. Beirut: Dār al-Qalam, pp. 179-183.</ref> Extracts from them appear in pseudo-Apollonius of Tyana's ''Sirr al-khalīqa wa-ṣanʿat al-ṭabīʿa'' ("The Secret of Creation and the Art of Nature", c. 750–850, see [[#Arabic alchemical Hermetica|above]]),<ref>Weisser 1980, pp. 68-69.</ref> in the ''[[Encyclopedia of the Brethren of Purity|Epistles of the Ikhwān al-Ṣafāʾ]]'' ("The Epistles of the Brethren of Purity", c. 900–1000),<ref>Plessner, Martin 1954. “Hermes Trismegistus and Arab Science” in: ''Studia Islamica'', 2, pp. 45-59, p. 58.</ref> in Maslama al-Qurṭubī's ''[[Picatrix|Ghāyat al-Ḥakīm]]'' ("The Aim of the [[Sage (philosophy)|Sage]]", 960, better known under its Latin title as ''Picatrix''),<ref>Van Bladel 2009, pp. 101-102.</ref> and in the works of the Persian philosopher [[Suhrawardi|Suhrawardī]] (1154–1191).<ref>Van Bladel 2009, p. 224.</ref> One of them was translated into Latin in the twelfth or thirteenth century under the title ''Liber Antimaquis''.<ref>Published by Burnett, Charles 2001. “Aristoteles/Hermes: Liber Antimaquis” in: Bos, Gerrit and Burnett, Charles and Lucentini, Paolo et al. (eds.). ''Hermetis Trismegisti Astrologica et Divinatoria''. Corpus Christianorum, CXLIV. Hermes Latinus, IV.IV. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 177-221.</ref> |

|||

* The '''''[[Cyranides]]''''' is a Greek work on healing magic which treats of the magical powers and healing properties of [[History of mineralogy|minerals]], [[History of botany|plants]] and [[History of zoology through 1859|animals]], for which it regularly cites Hermes as a source. It was translated into Arabic in the ninth century, but in this translation all references to Hermes seem to have disappeared.<ref>Van Bladel 2009, p. 17, note 45, p. 21, note 60. The Arabic version of the first book was edited by Toral-Niehoff, Isabel 2004. ''Kitab Giranis. Die arabische Übersetzung der ersten Kyranis des Hermes Trismegistos und die griechischen Parallelen''. München: Herbert Utz. The Arabic fragments of the other books were edited by Ullmann, Manfred 2020. “Die arabischen Fragmente der Bücher II bis IV der Kyraniden” in: ''Studia graeco-arabica'', 10, pp. 49-58.</ref> |

|||

* The '''''Sharḥ Kitāb Hirmis al-Ḥakīm fī Maʿrifat Ṣifat al-Ḥayyāt wa-l-ʿAqārib''''' ("The Commentary on the Book of the Wise Hermes on the Properties of Snakes and Scorpions"): a treatise on the [[Toxicology#History|venom]] of snakes an other poisonous animals.<ref>Ullmann, Manfred 1994. ''Das Schlangenbuch des Hermes Trismegistos''. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz; cf. Van Bladel 2009, p. 17.</ref> |

|||

* The '''''Dāʾirat al-aḥruf al-abjadiyya''''' (The Circle of Letters of the Alphabet"): a practical treatise on letter magic attributed to Hermes.<ref>Bonmariage, Cécile and Moureau, Sébastien 2016. ''Le Cercle des lettres de l’alphabet (Dā’irat al-aḥruf al-abjadiyya). Un traité de magie pratique des lettres attribué à Hermès. Édition critique, traduction annotée et étude''. Leiden: Brill.</ref> |

|||

==The religio-philosophical ''Hermetica''== |

|||

Contrary to the so-called 'technical' ''Hermetica'', whose writing began in the early [[Hellenistic period]] and continued deep into the [[Middle Ages]], the extant religio-philosophical ''Hermetica'' were for the most part produced in a relatively short period of time, i.e., between c. 100 and c. 300 CE.<ref>Copenhaver 1992, p. xliv; Bull 2018, p. 32. The sole exception is ''[[Definitions of Hermes Trismegistus to Asclepius|The Definitions of Hermes Trismegistus to Asclepius]]'', which may date to the first century CE (see Bull 2018, p. 9, referring to Mahé, Jean-Pierre 1978-1982. ''Hermès en Haute-Egypte''. Vol. I-II. Quebec: Presses de l'Université Laval, vol. 2, p. 278; cf. Mahé, Jean-Pierre 1999. "The Definitions of Hermes Trismegistus to Asclepius" in: Salaman, Clement et al. (eds.). ''The Way of Hermes''. London: Duckworth, pp. 99–122, p. 101). Earlier dates have been suggested, most notably by [[Flinders Petrie]] (500–200 BCE) and Bruno H. Stricker (c. 300 BCE), but these suggestions have been rejected by most other scholars (see Bull 2018, p. 6, note 23). Some Hermetic treatises of a generally 'religio-philosophical' nature were written in later periods (e.g., the ''Kitāb fi zajr al-nafs'' or "The Book of the Rebuke of the Soul", dating from the twelfth century), but these appear to be rather rare, and it is not clear whether they bear any relation to the early Greek treatises; see Van Bladel 2009, p. 226.</ref> They regularly take the form of dialogues between Hermes Trismegistus and his disciples Tat, Asclepius, and Ammon, and mostly deal with philosophical [[philosophical anthropology|anthropology]], [[Cosmology (philosophy)|cosmology]], and [[philosophical theology|theology]].<ref>Bull 2018, p. 3.</ref> The following is a list of all known works in this category: |

|||

===''Corpus Hermeticum''=== |

|||

[[File:Corpus Hermeticum.jpg|thumb|First Latin edition of the ''Corpus Hermeticum'', translated by [[Marsilio Ficino]], 1471 CE.]] |

|||

Undoubtedly the most famous among the religio-philosophical ''Hermetica'' is the '''''Corpus Hermeticum''''', a selection of seventeen [[Ancient Greek|Greek]] treatises that was first compiled by [[Byzantine]] editors, and translated into Latin in the fifteenth century by [[Marsilio Ficino]] (1433–1499) and [[Lodovico Lazzarelli]] (1447–1500).<ref>Copenhaver 1992, pp. xl-xliii.</ref> Ficino translated the first fourteen treatises (I–XIV), while Lazzarelli translated the remaining three (XVI–XVIII).<ref>See Hanegraaff, Wouter J. 2006. "Lazzarelli, Lodovico" in: Hanegraaff, Wouter J. et al. (eds.). ''Dictionary of Gnosis and Western Esotericism''. Leiden/Boston: Brill, pp. 679-683, p. 680. The Chapter no. XV of early modern editions was once filled with an entry from the [[Suda]] (a tenth-century Byzantine encyclopedia) and three excerpts from Hermetic works preserved by [[Stobaeus|Joannes Stobaeus]] (fl. fifth century, see [[#The Stobaean excerpts|below]]), but this chapter was left out in later editions, which therefore contain no chapter XV (see Copenhaver 1992, p. xlix).</ref> The name of this collection is somewhat misleading, since it contains only a very small selection of extant Hermetic texts (whereas the word [https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/corpus#English corpus] is usually reserved for the entire body of extant writings related to some author or subject). Its individual treatises were quoted by many early authors from the second and third centuries on, but the compilation as such is first attested only in the writings of the [[Byzantine philosophy|Byzantine philosopher]] [[Michael Psellos|Michael Psellus]] (c. 1017–1078).<ref>Copenhaver 1992, p. xlii.</ref> |

|||

The most well known among the treatises contained in this compilation is its opening treatise, which is called the '''''[[Poimandres]]'''''. However, at least until the nineteenth century, this name (under various forms, such ''Pimander'' or ''Pymander'') was also commonly used to designate the compilation as a whole.<ref>See, e.g., the English translation by [[John Everard (preacher)|Everard, John]] 1650. ''The Divine Pymander of Hermes Mercurius Trismegistus''. London.</ref> |

|||

In 1462 Ficino was working on a Latin translation of the collected works of [[Plato]] for his patron [[Cosimo de' Medici]] (the first member of the famous [[House of Medici|de' Medici family]] who ruled [[Florence]] during the [[Italian Renaissance]]), but when a manuscript of the ''Corpus Hermeticum'' became available, he immediately interrupted his work on Plato in order to start translating the works of Hermes, which were thought to be much more ancient, and therefore much more authoritative, than those of Plato.<ref>Copenhaver 1992, pp. xlvii-xlviii.</ref> This translation provided a seminal impetus in the development of [[Renaissance humanism|Renaissance thought and culture]], having a profound impact on the flourishing of [[alchemy]] and [[Renaissance magic|magic]] in early modern Europe, as well as influencing philosophers such as Ficino's student [[Pico della Mirandola]] (1463–1494), [[Giordano Bruno]] (1548–1600), [[Francesco Patrizi]] (1529–1597), [[Robert Fludd]] (1574–1637), and many others.<ref>Ebeling, Florian 2007. ''The Secret History of Hermes Trismegistus: Hermeticism from Ancient to Modern Times''. Ithaca: Cornell university press, pp. 68-70.</ref> |

|||

===''Asclepius''=== |

|||

The '''''Asclepius''''' (also known as the ''Perfect Discourse'', from Greek ''Logos teleios'') mainly survives in a Latin translation, though some Greek and [[Coptic language|Coptic]] fragments are also extant.<ref>Copenhaver 1992, pp. xliii-xliv.</ref> It is the only Hermetic treatise belonging to the religio-philosophical category that remained available to Latin readers throughout the Middle Ages.<ref>Copenhaver 1992, pp. xlvii.</ref> |

|||

===''Definitions of Hermes Trismegistus to Asclepius''=== |

|||

The '''''[[Definitions of Hermes Trismegistus to Asclepius]]''''' is a collection of [[Aphorism|aphorisms]] that has mainly been preserved in a sixth-century CE [[Armenian language|Armenian]] translation, but which likely goes back to the first century CE. The main argument for this early dating is the fact that some of its aphorisms are cited in multiple independent Greek Hermetic works. According to [[Jean-Pierre Mahé]], these aphorisms contain the core of the teachings which are found in the later Greek religio-philosophical ''Hermetica''.<ref>Mahé, Jean-Pierre 1999. "The Definitions of Hermes Trismegistus to Asclepius" in: Salaman, Clement et al. (eds.). ''The Way of Hermes''. London: Duckworth, pp. 99–122, pp. 101-108; cf. Bull 2018, p. 9.</ref> |

|||

===The Stobaean excerpts=== |

|||

In fifth-century [[Macedonia (Roman province)|Macedonia]] (northern Greece), [[Stobaeus|Joannes Stobaeus]] or "John of [[Stobi]]" compiled a huge ''Anthology'' of Greek poetical, rhetorical, historical, and philosophical literature in order to educate his son Septimius. Though [[Epitome|epitomized]] by later [[Byzantine]] copyists, it still remains a treasure trove of information about ancient philosophy and literature which would otherwise be entirely lost.<ref>Litwa, M. David 2018. ''Hermetica II: The Excerpts of Stobaeus, Papyrus Fragments, and Ancient Testimonies in an English Translation with Notes and Introductions''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 19.</ref> Among the excerpts of ancient philosophical literature preserved by Stobaeus are also a significant number of discourses and dialogues attributed to Hermes.<ref>Translated by Litwa 2018, pp. 27-159.</ref> While mostly related to the religio-philosophical treatises as found in the ''Corpus Hermeticum'', they also contains some material that is rather more of a 'technical' nature. Perhaps the most famous of the Stobaean excerpts, and also the longest, is the '''''Korē kosmou''''' ("The Daughter of the Cosmos").<ref>Copenhaver 1992, p. xxxviii; cf. Bull 2018, pp. 101-111.</ref> |

|||

===Hermes among the Nag Hammadi findings=== |

|||

Among the [[Coptic language|Coptic]] treatises which were found in 1945 in the [[Upper Egypt|Upper Egyptian]] town of [[Nag Hammadi]] (the [[Nag Hammadi library]]), there are also three treatises attributed to Hermes Trismegistus. Like all documents found in Nag Hammadi, these were translated from the Greek.<ref>Robinson, James M. 1990. ''The Nag Hammadi Library in English''. 3th, revised edition. New York: HarperCollins, pp. 12-13.</ref> They consist of some fragments from the ''Asclepius'' (VI,8; mainly preserved in Latin, see [[#Asclepius|above]]), ''The Prayer of Thanksgiving'' (VI,7) with an accompanying scribal note (VI,7a), and an important new text called the '''''[[Discourse on the Eighth and Ninth]]''''' (VI,6).<ref>Copenhaver 1992, p. xliv. These were all translated by James Brashler, Peter A. Dirkse and Douglas M. Parrott in: Robinson, James M. 1990. ''The Nag Hammadi Library in English''. 3th, revised edition. New York: HarperCollins, pp. 321-338.</ref> |

|||

===The Oxford and Vienna fragments=== |

|||

A number of short fragments from some otherwise unknown Hermetic works are preserved in a [[manuscript]] at the Bodleian Library in [[Oxford]], dealing with the soul, the senses, law, psychology, and embryology.<ref>Paramelle, Joseph and Mahé, Jean-Pierre 1991. "Extraits hermétiques inédits dans un manuscrit d’Oxford" in: ''Revue des Études Grecques'', 104, pp. 109-139. Translated by Litwa, M. David 2018. ''Hermetica II: The Excerpts of Stobaeus, Papyrus Fragments, and Ancient Testimonies in an English Translation with Notes and Introductions''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 161-169.</ref> Four short fragments from what once was a collection of ten Hermetic treatises, one of which was called "On Energies", are also preserved in a [[papyrus]] now housed in [[Vienna]].<ref> Mahé, Jean-Pierre 1984. "Fragments hermétiques dans les papyri Vindobonenses graecae 29456r et 29828r" in: Lucchesi, E. and Saffrey, H. D. (eds.). ''Mémorial André-Jean Festugière: Antiquité païenne et chrétienne''. Geneva: Cramer, pp. 51-64, 60. Translated by Litwa 2018, pp. 171-174. |

|||

</ref> |

|||

==History of scholarship on the ''Hermetica''== |

|||

During the [[Renaissance]], all texts attributed to Hermes Trismegistus were still generally believed to be of ancient Egyptian origin (i.e., to date from before the time of [[Moses]], or even from before the [[Genesis flood narrative|flood]]). In the early seventeenth century, the classical scholar [[Isaac Casaubon]] (1559–1614) demonstrated that some of the Greek texts betrayed too recent a vocabulary, and must rather date from the late [[Hellenistic]] or early Christian period.<ref>Copenhaver, Brian P. 1992. ''Hermetica: The Greek Corpus Hermeticum and the Latin Asclepius in a New English Translation, with Notes and Introduction''. Cambridge University Press, p. l.</ref> This conclusion was reaffirmed in the early twentieth century by the work of scholars like [[C. H. Dodd]].<ref>In his Dodd, Charles H. 1935. ''The Bible and the Greeks''. London: Hodder & Stoughton; see Copenhaver 1992, pp. l, lvii.</ref> More recent research, while reaffirming the dating of the earliest Greek treatises in the period of [[Syncretism|syncretic]] cultural ferment in [[Ptolemaic Kingdom|Hellenistic]] and [[Roman Egypt|Roman]] Egypt, suggests more continuity with the culture of ancient Egypt than had previously been believed.<ref>Mahé, Jean-Pierre 1978-1982. ''Hermès en Haute-Egypte''. Vol. I-II. Quebec: Presses de l'Université Laval; Fowden, Garth 1986. ''The Egyptian Hermes: A Historical Approach to the Late Pagan Mind''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; Bull, Christian H. 2018. ''The Tradition of Hermes Trismegistus: The Egyptian Priestly Figure as a Teacher of Hellenized Wisdom''. Leiden: Brill.</ref> The earliest Greek Hermetic treatises contain many parallels with Egyptian prophecies and hymns to the gods, and close comparisons can be found with Egyptian [[wisdom literature]], which (like many of the early Greek ''Hermetica'') is characteristically couched in words of advice from a "father" to a "son".<ref>Mahé, Jean-Pierre 1996. "Preliminary Remarks on the Demotic 'Book of Thoth' and the Greek Hermetica" in: ''Vigiliae Christianae'', 50(4), pp. 353-363, 358f.</ref> It has also been shown that some [[Demotic (Egyptian)|Demotic]] (late Egyptian) [[Papyrus|papyri]] contain substantial sections of a dialogue of the Hermetic type between [[Thoth]] and a disciple.<ref>See Jasnow, Richard and Zausich, Karl-Th. 1995. "A Book of Thoth?", paper given at the 7th International Congress of Egyptologists, Cambridge, 3–9 September 1995; Jasnow, Richard 2016. "Between Two Waters: The Book of Thoth and the Problem of Greco-Egyptian Interaction" in: Rutherford, Ian (ed.). ''Greco-Egyptian Interactions: Literature, Translation, and Culture, 500 BCE - 300 CE''. Oxford University Press.</ref> |

|||

In contradistinction to the early Greek religio-philosophical ''Hermetica'', which have been studied from a scholarly perspective since the early seventeenth century, the 'technical' ''Hermetica'' (both the early Greek treatises and the later Arabic and Latin works) remain largely unexplored by modern scholarship.<ref>Cf. Van Bladel 2009, p. 17.</ref> |

|||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

{{col-list|colwidth=25em| |

|||

*[[Alchemy]] |

|||

*[[Ancient Egypt|Ancient]], [[Ptolemaic Kingdom|Hellenistic]], and [[Roman Egypt|Roman]] Egypt |

|||

*[[History of astrology|Astrology]] |

|||

*[[Hellenistic Judaism]] |

|||

*[[Hellenistic period]] (general) |

|||

*[[Hellenistic philosophy]] |

|||

*[[Hellenistic religion]] |

|||

*[[Hermes Trismegistus]] |

|||

*[[Hermeticism]] |

*[[Hermeticism]] |

||

*[[ |

*[[Emerald Tablet]] |

||

*[[Magic (supernatural)|Magic]] ([[Magic in the Greco-Roman world|Hellenistic]], [[Medieval European magic|medieval European]], [[Renaissance magic|Renaissance]]) |

|||

*[[Hermetic seal]] |

|||

*[[Middle Platonism]] |

|||

*[[Sage (philosophy)]] |

|||

*[[Stoic physics|Stoic cosmology and theology]] |

|||

*[[Syncretism]] |

|||

*[[Talisman]] |

|||

*[[Theurgy]] |

|||

*[[Wisdom literature]] |

|||

}} |

|||

==References== |

==References== |

||

| Line 83: | Line 134: | ||

==Bibliography== |

==Bibliography== |

||

===English translations of Hermetic texts=== |

|||

Some pieces of Hermetica have been translated into English multiple times by modern [[Hermeticism|Hermeticists]]. However, the following list is strictly limited to scholarly translations: |

|||

* Copenhaver, Brian P. 1992. ''Hermetica: The Greek Corpus Hermeticum and the Latin Asclepius in a New English Translation, with Notes and Introduction''. Cambridge University Press. {{ISBN|0-521-42543-3}} |

|||

* Litwa, M. David 2018. ''Hermetica II: The Excerpts of Stobaeus, Papyrus Fragments, and Ancient Testimonies in an English Translation with Notes and Introductions''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. |

|||

* Mahé, Jean-Pierre 1999. "The Definitions of Hermes Trismegistus to Asclepius" in: Salaman, Clement et al. (eds.). ''The Way of Hermes''. London: Duckworth, pp. 99–122. |

|||

* Robinson, James M. 1990. ''The Nag Hammadi Library in English''. 3th, revised edition. New York: HarperCollins. (contains translations of some fragments from the ''Asclepius'' (VI,8), ''The Prayer of Thanksgiving'' (VI,7) with its accompanying scribal note (VI,7a), and the ''Discourse on the Eighth and Ninth'' (VI,6) by James Brashler, Peter A. Dirkse and Douglas M. Parrott, pp. 321-338) |

|||

* Waegeman, Maryse 1986. ''Amulet and Alphabet: Magical Amulets in the First Book of Cyranides''. Amsterdam. |

|||

===Secondary literature=== |

|||

* Bull, Christian H. 2018. ''The Tradition of Hermes Trismegistus: The Egyptian Priestly Figure as a Teacher of Hellenized Wisdom''. Leiden: Brill. |

* Bull, Christian H. 2018. ''The Tradition of Hermes Trismegistus: The Egyptian Priestly Figure as a Teacher of Hellenized Wisdom''. Leiden: Brill. |

||

* Ebeling, Florian 2007. ''The Secret History of Hermes Trismegistus: Hermeticism from Ancient to Modern Times''. Ithaca: Cornell university press. |

|||

* Copenhaver, Brian P. 1992. ''Hermetica: The Greek Corpus Hermeticum and the Latin Asclepius in a New English Translation, with Notes and Introduction''. Cambridge University Press. {{ISBN|0-521-42543-3}} The standard English translation, based on the Budé edition of the ''Corpus'' (1946–54). |

|||

* Everard, John 1650. ''The Divine Pymander of Hermes Mercurius Trismegistus''. London ((English translation) |

|||

* Festugière, André-Jean 1944-1954. ''La Révélation d'Hermès Trismégiste''. Vol. I-IV. Paris: Gabalda. |

* Festugière, André-Jean 1944-1954. ''La Révélation d'Hermès Trismégiste''. Vol. I-IV. Paris: Gabalda. |

||

* Festugière, André-Jean 1967. ''Hermétisme et mystique païenne''. Paris: Aubier Montaigne. |

* Festugière, André-Jean 1967. ''Hermétisme et mystique païenne''. Paris: Aubier Montaigne. |

||

* Fowden, Garth 1986. ''The Egyptian Hermes: A Historical Approach to the Late Pagan Mind''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. |

* Fowden, Garth 1986. ''The Egyptian Hermes: A Historical Approach to the Late Pagan Mind''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. |

||

* Jasnow, Richard and Zausich, Karl-Th. 1995. "A Book of Thoth?", paper given at the 7th International Congress of Egyptologists, Cambridge, 3–9 September 1995. |

|||

* Litwa, M. David 2018. ''Hermetica II: The Excerpts of Stobaeus, Papyrus Fragments, and Ancient Testimonies in an English Translation with Notes and Introductions''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. |

|||

* Jasnow, Richard 2016. "Between Two Waters: The Book of Thoth and the Problem of Greco-Egyptian Interaction" in: Rutherford, Ian (ed.). ''Greco-Egyptian Interactions: Literature, Translation, and Culture, 500 BCE - 300 CE''. Oxford University Press. |

|||

* Kraus, Paul 1942-1943. ''Jâbir ibn Hayyân: Contribution à l'histoire des idées scientifiques dans l'Islam. I. Le corpus des écrits jâbiriens. II. Jâbir et la science grecque''. Cairo: Institut français d'archéologie orientale. (vol. II, pp. 270-303 about pseudo-Apollonius of Tyana's ''Sirr al-khalīqa'' or "The Secret of Creation") |

|||

* Lucentini, Paolo et al. (eds.). ''Hermetism from Late Antiquity to Humanism. La tradizione ermetica dal mondo tardo-antico all'umanesimo. Atti del Convegno internazionale di studi, Napoli, 20-24 novembre 2001''. Turnhout: Brepols. |

|||

* Mahé, Jean-Pierre 1978-1982. ''Hermès en Haute-Egypte''. Vol. I-II. Quebec: Presses de l'Université Laval. |

* Mahé, Jean-Pierre 1978-1982. ''Hermès en Haute-Egypte''. Vol. I-II. Quebec: Presses de l'Université Laval. |

||

* Mahé, Jean-Pierre 1996. "Preliminary Remarks on the Demotic 'Book of Thoth' and the Greek Hermetica" in: ''Vigiliae Christianae'', 50(4), pp. 353-363. |

|||

* Nock, Arthur Darby and Festugière, André-Jean 1945-1954 (eds.). ''Corpus Hermeticum''. 4 vols. Paris: Belles Lettres. (critical edition of the CH, Asclepius, Stobaean fragments) |

|||

* Nock, Arthur Darby and Festugière, André-Jean 1945-1954 (eds.). ''Corpus Hermeticum''. 4 vols. Paris: Belles Lettres. (critical edition of the Greek text of the ''Corpus Hermeticum'' and the Stobaean excerpts; critical edition of the Latin text of the ''Asclepius'') |

|||

* Pearson, Birger 1981. “Jewish Elements in Corpus Hermeticum I (Poimandres)” in: Van den Broek, Roelof and Vermaseren, Maarten J. (eds.). ''Studies in Gnosticism and Hellenistic Religions presented to Gilles Quispel on the Occasion of his Sixty-Fifth Birthday''. Leiden: Brill, pp. 336-348. |

* Pearson, Birger 1981. “Jewish Elements in Corpus Hermeticum I (Poimandres)” in: Van den Broek, Roelof and Vermaseren, Maarten J. (eds.). ''Studies in Gnosticism and Hellenistic Religions presented to Gilles Quispel on the Occasion of his Sixty-Fifth Birthday''. Leiden: Brill, pp. 336-348. |

||

* Plessner, Martin 1954. “Hermes Trismegistus and Arab Science” in: ''Studia Islamica'', 2, pp. 45-59. |

|||

* Ruska, Julius 1926. ''Tabula Smaragdina. Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der hermetischen Literatur''. Heidelberg: Winter. |

|||

* Van Bladel, Kevin 2009. ''The Arabic Hermes: From Pagan Sage to Prophet of Science''. Oxford: Oxford University Press. |

* Van Bladel, Kevin 2009. ''The Arabic Hermes: From Pagan Sage to Prophet of Science''. Oxford: Oxford University Press. |

||

* Vereno, Ingolf 1992. ''Studien zum ältesten alchemistischen Schrifttum. Auf der Grundlage zweier erstmals edierter arabischer Hermetica''. Islamkundliche Untersuchungen, band 155. Berlin: Klaus Schwarz Verlag. |

|||

* Weisser, Ursula 1980. ''Das Buch über das Geheimnis der Schöpfung von Pseudo-Apollonios von Tyana''. Berlin: De Gruyter. |

|||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

* [http://www.gnosis.org/library/hermet.htm ''The Corpus Hermeticum'']. G. R. S. Mead's translations taken from his work, ''Thrice Greatest Hermes: Studies in Hellenistic Theosophy and Gnosis, Volume II''. (The Gnostic Society Library) |

|||

* [http://www.levity.com/alchemy/corpherm.html Everard's translation ''The Divine Pymander in XVII books'' at Adam McLean's Alchemy Web Site] |

|||

* [http://www.granta.demon.co.uk/arsm/jg/corpus.html Jeremiah Genest, ''Corpus Hermeticum''] |

|||

* [http://www.w66.eu/elib/html/poimandres.html Ἑρμου του Τρισμεγιστου ΠΟΙΜΑΝΔΡΗΣ] – Greek text of the ''Poimandres'' |

|||

* [https://thehermetica.files.wordpress.com/2015/05/the-hermetic-order.pdf The Hermetic Order] History and introduction to hermeticism including excerpts from the ''Corpus Hermeticum'' |

|||

* The Gnostic Society Library hosts translations of the [http://www.gnosis.org/library/hermet.htm#CH ''Corpus Hermeticum''], the [http://www.gnosis.org/library/grs-mead/TGH-v2/th237.html ''Asclepius''], [http://www.gnosis.org/library/grs-mead/TGH-v3/index.html the Stobaean excerpts], and [http://www.gnosis.org/library/grs-mead/TGH-v3/index.html some ancient testimonies on Hermes] (all taken from [[G.R.S. Mead|Mead, George R. S.]] 1906. ''Thrice Greatest Hermes: Studies in Hellenistic Theosophy and Gnosis''. Vols. 2-3. London: Theosophical Publishing Society; note that these translations are outdated and were written by a member of the [[Theosophical Society]]; modern scholarly translation are found [[#English translations of Hermetic texts|above]]), as well as translations of the [http://www.gnosis.org/library/hermet.htm#NHL three Hermetic treatises in the Nag Hammadi findings] (reproduced with permission from the translations prepared by James Brashler, Peter A. Dirkse and Douglas M. Parrott as originally published in: Robinson, James M. 1978. ''The Nag Hammadi Library in English''. Leiden: Brill). |

|||

{{Alchemy}} |

|||

[[Category:Alchemical documents]] |

[[Category:Alchemical documents]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Alchemy]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Ancient Egypt]] |

||

[[Category:Ancient Egyptian texts]] |

|||

[[Category:Astrological texts]] |

|||

[[Category:Astrology]] |

|||

[[Category:Grimoires]] |

|||

[[Category:Hellenistic philosophy]] |

|||

[[Category:Hellenistic religion]] |

|||

[[Category:Hermeticism]] |

[[Category:Hermeticism]] |

||

[[Category:History of ideas]] |

[[Category:History of ideas]] |

||

[[Category:Magic (supernatural)]] |

|||

[[Category:Medieval philosophy]] |

|||

[[Category:Medieval philosophical literature]] |

|||

[[Category:Wisdom literature]] |

[[Category:Wisdom literature]] |

||

Revision as of 19:24, 15 January 2021

| Part of a series on |

| Hermeticism |

|---|

|

The Hermetica are the philosophical texts attributed to the legendary Hellenistic figure Hermes Trismegistus (a syncretic combination of the Greek god Hermes and the Egyptian god Thoth).[1] These texts may vary widely in content and purpose, but are usually subdivided into two main categories:

- The so-called 'technical' Hermetica: this category contains treatises dealing with astrology, medicine and pharmacology, alchemy, and magic, the oldest of which were written in Greek and may go back as far as to the second or third century BCE.[2] Many of the texts belonging to this category were later translated into Arabic and Latin, often being extensively revised and expanded throughout the centuries. Some of them were also originally written in Arabic, though in many cases their status as an original work or translation remains unclear.[3] These Arabic and Latin Hermetic texts were widely copied throughout the Middle Ages (the most famous example being the Emerald Tablet).

- The so-called 'philosophical' Hermetica: this category contains religio-philosophical treatises which were mostly written in the second and third centuries CE, though the very earliest of them may go back to the first century CE.[4] They are chiefly focused on the relationship between human beings, the cosmos, and God (thus combining philosophical anthropology, cosmology, and theology), and on moral exhortations calling for a way of life (the so-called 'way of Hermes') leading to spiritual rebirth, and eventually to apotheosis in the form of a heavenly ascent.[5] The treatises in this category were probably all originally written in Greek, even though some of them only survive in Coptic, Armenian, or Latin translations.[6] During the Middle Ages, most of them were only accessible to Byzantine scholars (an important exception being the Asclepius, which mainly survives in an early Latin translation), until a compilation of Greek Hermetic treatises known as the Corpus Hermeticum was translated into Latin by the Renaissance scholars Marsilio Ficino (1433–1499) and Lodovico Lazzarelli (1447–1500).[7]

Though strongly influenced by Greek and Hellenistic philosophy (especially Platonism and Stoicism),[8] and to a lesser extent also by Jewish ideas,[9] many of the early Greek Hermetic treatises do contain distinctly Egyptian elements, most notably in their affinity with the traditional Egyptian wisdom literature.[10] This used to be the subject of much doubt,[11] but it is now generally admitted that the Hermetica as such did in fact originate in Hellenistic and Roman Egypt,[12] even if most of the later Hermetic writings (which continued to be composed at least until the twelfth century CE) clearly did not.[13] It may perhaps even be the case that the great bulk of the early Greek Hermetica were written by Hellenizing members of the Egyptian priestly class, whose intellectual activity was centred in the environment of the Egyptian temples.[14]

The technical Hermetica

Greek

Greek astrological Hermetica

The oldest known texts associated with Hermes Trismegistus are a number of astrological works which may go back as far as to the second or third century BCE:

- The Salmeschoiniaka (the "Wandering of the Influences"), perhaps composed in Alexandria in the second or third century BCE, deals with the configurations of the stars.[15]

- The Nechepsos-Petosiris texts are a number of anonymous works dating to the second century BCE which were falsely attributed to the Egyptian king Necho II (610–595 BCE, referred to in the texts as Nechepsos) and his legendary priest Petese (referred to in the texts as Petosiris). These texts, only fragments of which survive, ascribe the astrological knowledge they convey to the authority of Hermes.[16]

- The Art of Eudoxus is a treatise on astronomy which was preserved in a second-century BCE papyrus and which mentions Hermes as an authority.[17]

- The Liber Hermetis ("The Book of Hermes") is an important work on astrology laying out the names of the decans (a distinctly Egyptian system which divided the zodiac into 36 parts). It survives only in an early (fourth- or fifth-century CE) Latin translation,[18] but contains elements that may be traced to the second or third century BCE.[19]

Other early Greek Hermetic works on astrology include:

- The Brontologion: a treatise on the various effects of thunder in different months.[20]

- The Peri seismōn ("On earthquakes"): a treatise on the relation between earthquakes and astrological signs.[21]

- The Book of Asclepius Called Myriogenesis: a treatise on astrological medicine.[22]

- The Holy Book of Hermes to Asclepius: a treatise on astrological botany describing the relationships between various plants and the decans.[23]

- The Fifteen Stars, Stones, Plants and Images: a treatise on astrological mineralogy and botany dealing with the effect of the stars on the pharmaceutical powers of minerals and plants.[24]

Greek alchemical Hermetica

Starting in the first century BCE, a number of Greek works on alchemy were attributed to Hermes Trismegistus. These are now all lost, except for a number of fragments (one of the larger of which is called Isis the Prophetess to her Son Horus) preserved in later alchemical works dating to the second and third centuries CE. Especially important is the use made of them by the Egyptian alchemist Zosimus of Panopolis (fl. c. 300 CE), who also seems to have been familiar with the religio-philosophical Hermetica.[25] Hermes' name would become more firmly associated with alchemy in the medieval Arabic sources (see below), of which it is not yet clear to what extent they drew on the earlier Greek literature.[26]

Greek magical Hermetica

- The Cyranides is a work on healing magic which treats of the magical powers and healing properties of minerals, plants and animals, for which it regularly cites Hermes as a source.[27] It was independently translated both into Arabic and Latin.[28]

- The Greek Magical Papyri are a modern collection of papyri dating from various periods between the second century BCE and the fifth century CE. They mainly contain practical instructions for spells and incantations, some of which cite Hermes as a source.[29]

Arabic

Many Arabic works attributed to Hermes Trismegistus still exist today, although the great majority of them have not yet been published and studied by modern scholars.[30] For this reason too, it is often not clear to what extent they drew on earlier Greek sources. The following is a very incomplete list of known works:

Arabic astrological Hermetica