Pantomime: Difference between revisions

m Undid revision 186420877 by 70.185.227.8 (talk) |

add link |

||

| Line 98: | Line 98: | ||

== External links == |

== External links == |

||

*[http://www.musicaltalk.co.uk/episodes_0018.html MusicalTalk Podcast] discussing British pantomime; its origins and traditions. |

*[http://www.musicaltalk.co.uk/episodes_0018.html MusicalTalk Podcast] discussing British pantomime; its origins and traditions. |

||

*[http://pantomime.com.ua Pantomime in Ukraine] |

|||

[[Category:Comedy]] |

[[Category:Comedy]] |

||

Revision as of 22:36, 25 January 2008

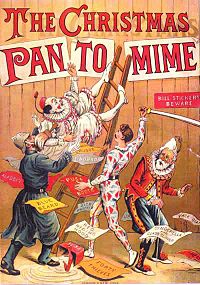

Pantomime (informally, panto), not to be confused with mime, refers to a theatrical genre, traditionally found in Great Britain, Canada, Australia, South Africa, New Zealand, Zimbabwe and Ireland, which is usually performed around the Christmas and New Year holiday season.

History

Origins and sources

A pantomimos in Greece was originally a solo dancer who 'imitated all' (panto- - all, mimos - mimic) accompanied by sung narrative and instrumental music, often played on the flute. The word later came to be applied to the performance itself.[1] The pantomime was an extremely popular form of entertainment in ancient Greece and, later, Rome. Like theatre, it encompassed the genres of comedy and tragedy. No ancient pantomime libretto has survived, partly because the genre was looked down upon by the literary elite. Nonetheless, notable ancient poets such as Lucan wrote for the pantomime, no doubt in part because the work was well paid[2]. In a speech of the late 1st cent. AD now lost, the orator Aelius Aristides condemned the pantomime for its erotic content and the "effeminacy" of its dancing[3].

The style and content of modern pantomime have very clear and strong links with the Commedia dell'arte, a form of popular theatre that arose in Italy in the early middle ages, and which reached England by the 16th century. A "comedy of professional artists" travelling from province to province in Italy and then France, they improvised and told stories which told lessons to the crowd and changed the main character depending on where they were performing. The great clown Grimaldi transformed the format. Each story had the same fixed characters: the lovers, father, servants (one being crafty and the other stupid), etc. These roles/characters can be found in today's pantomimes.

The gender role reversal resembles the old festival of Twelfth Night, a combination of Epiphany and midwinter feast, when it was customary for the natural order of things to be reversed. This tradition can be traced back to pre-Christian European festivals such as Samhain and Saturnalia.

Development as a distinctly British entertainment

The Pantomime first arrived in England as entr'actes between opera pieces, eventually evolving into separate shows.

In Restoration England, a pantomime was considered a low form of opera, rather like the Commedia dell'arte but without Harlequin (rather like the French Vaudeville). In 1717, actor and manager John Rich introduced Harlequin to the British stage under the name of "Lun" (for "lunatic") and began performing wildly popular pantomimes. These pantomimes gradually became more topical and comic, often involving as many special theatrical effects as possible. Colley Cibber and his colleagues competed with Rich and produced their own pantomimes, and pantomime was a substantial (if decried) subgenre in Augustan drama. According to some sources, the Lincoln's Inn Field Theatre and the Drury Lane Theatre were the first to stage something like real pantomimes (in the later sense that has become codified with its fairly rigid set of conventions) creating high competition between them to create the more elaborate show. As manager of Drury Lane in the 1870s, Augustus Harris is now considered the father of modern pantomime. This form had virtually died out by the end of the 19th century.

There seems to be some scholarly disagreement as to exactly when the true pantomime genre gets started. According to one eminent authority, Russell A. Peck (the John Hall Deane Professor of English at the University of Rochester [1]),"The first Cinderella Pantomime in England was the 1804 production at Drury Lane, dir. Mr. Byrne," [2] with music by Michael Kelly (1762-1826). This date would seem too early for panto in its mature form, with its extensive adherence to a set of conventions including the pantomime dame role, the principal boy played by a young woman, the animal-costume roles, audience participation, etc. But if Peck means that this was the first pantomime in England in the older sense of "low opera", then his date seems too late, for he seems to disregard the fact that pantomime as "low opera" had already arisen in Restoration-era England, considerably prior to 1804. But of course, this date only applies to pantomime productions of the Cinderella tale, not of other tales. Yet even limiting this claim to Cinderella, one finds that other sources give 1870 as the date of the first Cinderella pantomime in England (see below).

Until the 20th century, British pantomimes were often concluded with a harlequinade, a free standing entertainment of slapstick.

Pantomime traditions and conventions

Traditionally performed at Christmas, with family audiences consisting mainly of children and parents, British pantomime is now a popular form of theatre, incorporating song, dance, buffoonery, slapstick, in-jokes, audience participation, and mild sexual innuendo. There are a number of traditional story-lines, and there is also a fairly well-defined set of performance conventions. Lists of these items follow, along with a special discussion of the "guest celebrity' tradition, which emerged in the late 19th century.

Traditional stories

Plots are often loosely based on traditional children's stories, including several written or popularized by the French pioneer of the 'fairy tale' genre, Charles Perrault. The most popular titles are:

- Aladdin (sometimes combined with Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves and/or other Arabian Nights tales)

- Babes in the Wood (often combined with Robin Hood)

- Beauty and the Beast

- Cinderella, the most popular of all pantomimes and first shown in 1870 in Covent Garden, London

- Dick Whittington, first staged as a pantomime in 1814, based on a 17th century play.

- Goldilocks and the Three Bears

- Jack and the Beanstalk

- Mother Goose

- Peter Pan

- Puss in Boots

- Sleeping Beauty

- Snow White

- Wizard of Oz, The

Performance conventions

The form has a number of conventions, some of which have changed or weakened a little over the years, and by no means all of which are obligatory.

- The leading male juvenile character (the "principal boy") - traditionally played by a young woman.

- An older woman (the pantomime dame - often the hero's mother) is usually played by a man in drag.

- Risqué double entendre, often wringing innuendo out of perfectly innocent phrases. This is, in theory, over the heads of the children in the audience.

- Audience participation, including calls of "look behind you!" (or "he's behind you!"), and "Oh, yes it is!" or "Oh, no it isn't!" The audience is always encouraged to "Boo" the villain, and "Awwwww" the poor victims, such as the rejected dame, who usually fancies the prince.

- A song combining a well-known tune with re-written lyrics. The audience is encouraged to sing the song; often one half of the audience is challenged to sing "their" chorus louder than the other half.

- The pantomime horse or cow, played by two actors in a single costume, one as the head and front legs, the other as the body and back legs.

- The good fairy always enters from stage right and the evil villain enters from stage left. In Commedia Dell 'Arte the right side of the stage symbolized Heaven and the left side symbolized Hell.

- The members of the cast throw out sweets to the children in the audience.

- Sometimes the story villain will squirt members of the audience with water guns or pretend to throw a bucket of "water" at the audience that is actually full of streamers

- A slapstick comedy routine may be performed, often a decorating or baking scene, with humour based around throwing messy substances.

Guest celebrity in pantomime

Another contemporary pantomime tradition is the celebrity guest star, a practice that dates back to the late 19th century, when Augustus Harris, proprietor of the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, hired well-known variety artists for his pantomimes.

Until the decline of the British music hall tradition by the late 1950s, many popular artists played in pantomimes across the country. Many modern pantomimes use popular artists to promote the pantomime, and the play is often adapted to allow the star to showcase their well-known act, even when such a spot has little relation to the plot, for example, Rolf Harris might perform Jake the Peg in a pantomime about Aladdin.

Nowadays, a pantomime occasionally pulls off a coup by engaging a guest star with an unquestionable thespian reputation, as was the case with the Christmas 2004 production of Aladdin that featured Sir Ian McKellen as Widow Twankey, which he reprised in the 2005 production at the Old Vic theatre in London.

As well as being an actor in the Shakespearean tradition, McKellen had become hugely famous with children as Gandalf in The Lord of the Rings and Magneto in X-Men. "At least we can tell our grandchildren that we saw McKellen's Twankey and it was huge," said Michael Billington, theatre critic of The Guardian, December 20, 2004, entering into the pantomime spirit of double entendre. In recent times, the in pantomimes have featured soap stars, comedians or former sportsmen rather as celebrity attractions, supplemented by jobbing actors and pantomime specialists.

York's Theatre Royal pantomime features no guest celebrities, but a regular cast headed by Berwick Kaler, who has played the dame there for 27 years.

Christopher Biggins has been a pantomime dame for 38 years running until 2007 when his attendance on I'm A Celebrity! Get Me Out of Here! made it impossible for him to do a panto that year.

Pantomime outside the United Kingdom

Pantomime in Australia

Pantomimes in Australia at Christmas have also always been very popular, and professional productions often feature celebrities. During the 1950s, a Christmas Cinderella pantomime in Sydney featured Danny Kaye as Buttons. There are also radio pantomimes at Christmas which are featured on the Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

On the other hand it is probably fair to say that the familiarity of young Australians with the genre has declined rather than risen since the middle of the last century, for all manner of reasons.

Pantomime in Canada

Pantomime in the United States

Pantomime, as described in this article, is seldom performed in the United States of America. As a consequence, the word "pantomime" is more commonly understood to refer to the art of mime, as was practised by Marcel Marceau or Nola Rae and is often assumed to be a solo performance seen as often on street corners as on stage. However, certain shows that came from the pantomime traditions, especially Peter Pan, are performed quite often, and there are a few American theatre companies which produce traditional British-style pantomime as well as American adaptations of the form.

Among recent American revivals (or transplantings) of the genre, the Hideout Players in Chicago have now presented two Christmas pantomimes which stay true to the English form. Jon Langford, a British singer and artist, plays the pantomime dame, and a pantomime whale ("Moby Duck," half-whale/half-duck) has eaten the villain on both occasions. The genre has also resurfaced in Baltimore, with a 2007-8 Christmas season panto production of Puss in Boots at the Theatre Project receiving favorable review in that city's paper of record, the Sun. According to the Sun, panto is "a theatrical style that Roger Brunyate [artistic director[3] of the Peabody Opera Theatre at the Peabody Institute], who wrote and directs this newly conceived Puss in Boots, remembers from his childhood in the United Kingdom."[4]

As for the earliest pantomime productions in the US, the above-cited Professor Peck[5] of the University of Rochester lists Cinderella pantomime productions in New York (March 1808), New York again (August 1808), Philadelphia (1824), and Baltimore (1839) [6]. But it is doubtful to what extent these early productions resembled pantomime by its current definition in England, which dates from about the last third of the 19th century.

Pantomime in the United Kingdom today

Many cities and provincial theatres throughout the United Kingdom now have an annual pantomime.

Pantomime is very popular with Amateur Dramatics societies throughout the UK, and the Pantomime season (roughly speaking, December to February) will see pantomime productions in many village halls and similar venues across the country.

References

External links

- MusicalTalk Podcast discussing British pantomime; its origins and traditions.

- Pantomime in Ukraine