Villain: Difference between revisions

by whom? who calls them this? "in film and literature" is vague, & unverifiable to say they're called this "in film & literature" as a whole. these are neologisms or synonyms. |

m →Etymology: image move to prevent breaking section syntax |

||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

== Etymology == |

== Etymology == |

||

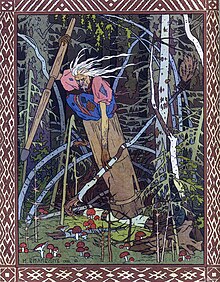

[[Image:Villains before going to Work receiving their Lord's Orders Miniature in the Proprietaire des Choses Manuscript of the Fifteenth Century Library of the Arsenal in Paris.png|thumb| |

[[Image:Villains before going to Work receiving their Lord's Orders Miniature in the Proprietaire des Choses Manuscript of the Fifteenth Century Library of the Arsenal in Paris.png|thumb|left|French villains in the 15th century.]] |

||

Villain comes from the [[Anglo-Norman language|Anglo-French]] and [[Old French]] ''vilein'', which itself descends from the Late Latin word '' villanus'' meaning "farmhand."<ref>{{cite book |title=Chambers Dictionary of Etymology |editor=Robert K. Barnhart |year=1988 |publisher=Chambers Harrap Publishers |location=New York |isbn=0-550-14230-4 |pages=1204}}</ref> Someone who is bound to the soil of a ''villa'', which is to say, worked on the equivalent of a [[plantation]] in [[Late Antiquity]], in Italy or [[Gaul]].<ref name=etymology>{{cite book|title=Webster's New World Dictionary| editor=David B. Guralnik| location=New York | publisher=[[Simon and Schuster]]| year=1984}}</ref> It referred to a person of less than knightly status and so came to mean a person who was not [[Chivalry|chivalrous]]. As a result of many unchivalrous acts, such as treachery or rape, being considered villainous, in the modern sense the word, it became used as a term of abuse and eventually took on its modern meaning.<ref>{{citebook|title=[[Studies in Words]]|author=[[C. S. Lewis]]|publisher=Cambridge University Press|year=1960}}</ref> |

Villain comes from the [[Anglo-Norman language|Anglo-French]] and [[Old French]] ''vilein'', which itself descends from the Late Latin word '' villanus'' meaning "farmhand."<ref>{{cite book |title=Chambers Dictionary of Etymology |editor=Robert K. Barnhart |year=1988 |publisher=Chambers Harrap Publishers |location=New York |isbn=0-550-14230-4 |pages=1204}}</ref> Someone who is bound to the soil of a ''villa'', which is to say, worked on the equivalent of a [[plantation]] in [[Late Antiquity]], in Italy or [[Gaul]].<ref name=etymology>{{cite book|title=Webster's New World Dictionary| editor=David B. Guralnik| location=New York | publisher=[[Simon and Schuster]]| year=1984}}</ref> It referred to a person of less than knightly status and so came to mean a person who was not [[Chivalry|chivalrous]]. As a result of many unchivalrous acts, such as treachery or rape, being considered villainous, in the modern sense the word, it became used as a term of abuse and eventually took on its modern meaning.<ref>{{citebook|title=[[Studies in Words]]|author=[[C. S. Lewis]]|publisher=Cambridge University Press|year=1960}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 21:14, 4 November 2008

A villain is an "evil" character in a story, whether a historical narrative or, especially, a work of fiction. The villain usually is the antagonist, the character who tends to have a negative effect on other characters. A female villain is sometimes called a villainess (often to differentiate her from a male villain). Random House Unabridged Dictionary defines villain as "a cruelly malicious person who is involved in or devoted to wickedness or crime; scoundrel; or a character in a play, novel, or the like, who constitutes an important evil agency in the plot."[1]

Etymology

Villain comes from the Anglo-French and Old French vilein, which itself descends from the Late Latin word villanus meaning "farmhand."[2] Someone who is bound to the soil of a villa, which is to say, worked on the equivalent of a plantation in Late Antiquity, in Italy or Gaul.[3] It referred to a person of less than knightly status and so came to mean a person who was not chivalrous. As a result of many unchivalrous acts, such as treachery or rape, being considered villainous, in the modern sense the word, it became used as a term of abuse and eventually took on its modern meaning.[4]

Folk and fairy tales

Vladimir Propp, in his analysis of the Russian fairy tales, concluded that a fairy tale had only eight dramatis personae, of which one was the villain,[5] and his analysis has been widely applied to non-Russian tales. The actions that fell into a villain's sphere were:

- a story-initiating villainy, where the villain caused harm to the hero or his family,

- a conflict between the hero and the villain, either a fight or other competition

- pursuing the hero after he has succeeded in winning the fight or obtaining something from the villain.

None of these acts must necessarily occur in a fairy tale, but when they occurred, the character that performed them was the villain. The villain therefore could appear twice: once in the opening of the story, and a second time as the person sought out by the hero.[6]

When a character performed only these acts, the character was a pure villain. Various villains also perform other functions in a fairy tale; a witch who fought the hero and ran away, which let the hero follow her, was also performing the task of "guidance" and thus acting as a helper.[7]

The functions could also be spread out among several characters. If a dragon acted as the villain but was killed by the hero, another character -- such as the dragon's sisters -- might take on the role of the villain and pursue the hero.[7]

Two other characters could appear in roles that are villainous in the more general sense. One is the false hero; this character is always villainous, presenting a false claim to be the hero that must be rebutted for the happy ending.[8] Among these characters are Cinderella's stepsisters, chopping off parts of their feet to fit on the shoe.[9] Another character, the dispatcher, sends a hero on his quest. This may be an innocent request, to fulfill a legitimate need, but the dispatcher may also, villainously, lie to send a character on a quest in hopes of being rid of him.[10]

The villainous foil

In fiction, villains commonly function in the dual role of adversary and foil to the story's heroes. In their role as adversary, the villain serves as an obstacle the hero must struggle to overcome. In their role as foil, the villain exemplifies characteristics that are diametrically opposed to those of the hero, creating a contrast distinguishing heroic traits from villainous ones.

Others point out that many acts of villains have a hint of wish-fulfillment [11], which makes some people identify with them as characters more strongly than with the heroes. Because of this, a convincing villain must be given a characterization that makes his or her motive for doing wrong convincing, as well as being a worthy adversary to the hero. As put by film critic Roger Ebert: "Each film is only as good as its villain. Since the heroes and the gimmicks tend to repeat from film to film, only a great villain can transform a good try into a triumph."[12]

The Evil Genius

The Evil Genius is an archetype or even a caricature that is a recurring staple in certain genres of fiction, particularly comic books, spy fiction, video games, action films and cartoons. The evil genius serves as a common adversary and foil of the hero. Evil geniuses are, as their name suggests, individuals of supreme intelligence who use their intellect for selfish and/or antisocial purposes. There is a general overlap with mad scientists but whereas mad scientists are more amoral than evil and often genuinely concerned with scientific progress, evil geniuses are usually portrayed as power hungry egotists, more interested in self-aggrandizement than anything else. Also mad scientists, despite their intellect are often reckless and don't think much about the consequences of their actions while evil geniuses are clever planners. For instance a mad scientist would create an army of zombies just to see if he could whereas an evil genius would have a diabolical use for the army as well as a plan to escape the area and avoid being killed.

Evil geniuses often exhibit the following:

- A tendency to revel in their villainy and mental superiority.

- A preference for intellectual stimulation.

- A vain, stylish, cat-like demeanour.

- A traumatic or impoverished childhood (ironically this is often the origin of the hero they oppose).

Villain archetypes

This article possibly contains original research. (October 2008) |

This article may contain excessive or irrelevant examples. |

Note that, as mentioned above, a villain's disposition towards evil distinguishes them from an antagonist. For example, Javert in Les Miserables is an antagonist: he opposes the hero, but does so by such means and under such pretexts as not to become entirely odious to the reader. Note also that a villain may repent, be redeemed, or become in league with the hero. Sometimes, a villain may even appear as the protagonist of a story, while the hero who opposes them may be the antagonist.

- Archenemy – The principal enemy of the hero. The reason why the particular villain stands out more than the rest varies; they may be the hero's strongest enemy, be the complete antithesis to the hero, have strong connections with their hero's past, pose the greatest threat, have caused the hero a great deal of suffering or loss, or may be the most recurring villain. Examples of Archenemy:

- The Joker

- Bowser from Mario (series)

- Sarah Kerrigan from Starcraft

- Dark Lord – a villain of near-omnipotence in his realm, who seeks to utterly dominate the world; he is often depicted as a diabolical force, and may, indeed, be more a force than a personality, and often personifies evil itself.[13] The effects of his rule often assert malign effects on the land as well as his subjects. Besides his usual magical abilities, he often controls great armies. Most Dark Lords are male, except in parody.[13] Example of popular Dark Lords:

- Darth Vader

- Sauron

- Lord Voldemort

- Chaos (Warhammer)

- Emperor Palpatine

- Jadis, the White Witch

- Wicked Witch of the West

- The Source of All Evil

- The Vizier from Prince of Persia Trilogy

- Ganon from the Legend of Zelda

- Anubis from Stargate SG-1

- Evil twin – a character which is identical or almost identical to the hero, but is evil instead of good. Examples of Evil Twin:

- Femme fatale – a beautiful, seductive but ultimately villainous woman who uses the malign power of her sexuality in order to ensnare the hapless hero into danger. Examples of femme fatale:

- Mad scientist – a scientist-villain or villain-scientist, a figure who represents the dangers of science in the wrong hands or abused for harmful purposes. Can easily be confused with Evil Genius. Examples of Mad scientists:

- Supervillain – a villain who displays special powers, skills or equipment powerful enough to be a typically serious challenge to a superhero. Like the superhero, the supervillain will often utilize colorful costumes and gimmicks that make them easily recognizable to readers. Example of supervillain:

- Sephiroth

- Green Goblin

- Sylar

- Ernst Stavro Blofeld from the James Bond books and films

- Tragic villain – a character who, although acting for primarily "evil" or selfish goals, is either not in full control of their actions or emotions, therefore the reader or viewer can sympathize for them. These villains can face a crisis of conscience in which they submit to doing evil. These villains often have confused morals believing that they are doing good when in fact they are doing evil. Examples of these include:

- Gollum in The Lord of the Rings

- Elric of Melñibone, from the novels of Michael Moorcock

- Mr. Freeze

- Norman Bates in the film Psycho

- Anakin Skywalker in the film Star Wars III: Revenge of the Sith

- Mr. Glass from Unbreakable

- Trickster – often more of an annoying nuisance than a fearsome or dangerous enemy, a trickster may take many forms, from a con man to a mischievous imp. Adventures with trickster type villains tend to be light and comedic and the hero typically finds a way to defeat them non-violently. Sometimes there may be a lesson learned from the trickster, even if unintentional. Examples include:

- Secondary villain – Often not very evil or competent. They are usually not as smart as they think they are and often are not ruthless enough to harm or murder. They are typically motivated by greed or vanity and are often not taken very seriously as a threat. They are not always criminals and sometimes may be guilty of nothing more than trying to win by cheating. They may serve as placeholders until the true villain appears. They may also reform and join the hero as comic relief characters. Examples include:

- Harry Mudd from Star Trek

- Draco Malfoy in the Harry Potter canon

- Dick Dastardly and Muttley

- Alternately, secondary villains may be the 'right hand man' for a powerful villain. Evil being what it is, loyalty is often in question and the character will likely attempt to take power for themself if the opportunity arises. Examples include:

- Evil Nature sometimes villains are forces of nature whose instinct is evil. Examples would be:

- Galactus

- Godzilla

- the physical embodiment of Death, in both Marvel Comics and DC Comics

See also

- Rogues gallery

- Mad scientist

- Supervillain

- List of Disney villains

- List of James Bond villains

- Evil laugh

- Evil Overlord List

- Filmfare Best Villain Award. Since 1991, Bollywood recognizes the best actors portraying a villain.

- El caballo del malo

- Evil Genius (video game)

References

- ^ Random House Unabridged Dictionary Web Result

- ^ Robert K. Barnhart, ed. (1988). Chambers Dictionary of Etymology. New York: Chambers Harrap Publishers. p. 1204. ISBN 0-550-14230-4.

- ^ David B. Guralnik, ed. (1984). Webster's New World Dictionary. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- ^ C. S. Lewis (1960). Studies in Words. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Vladimir Propp, Morphology of the Folk Tale, p 79 ISBN 0-292-78376-0

- ^ Vladimir Propp, Morphology of the Folk Tale, p 84 ISBN 0-292-78376-0

- ^ a b Vladimir Propp, Morphology of the Folk Tale, p 81 ISBN 0-292-78376-0

- ^ Vladimir Propp, Morphology of the Folktale, p60, ISBN 0-292-78376-0

- ^ Maria Tatar, The Annotated Brothers Grimm, p 136 ISBN 0-393-05848-4

- ^ Vladimir Propp, Morphology of the Folktale, p77, ISBN 0-292-78376-0

- ^ [1]

- ^ Review of Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan by Roger Ebert.

- ^ a b John Grant and John Clute, The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, "Dark Lord", p 250 ISBN 0-312-19869-8

Further reading

- Zawacki's humorous look at the concept of a villain:

- Neil Zawacki (2001). "So You've Decided to be Evil". Dark Sites.

- Neil Zawacki (2003). How to Be a Villain: Evil Laughs, Secret Lairs, Master Plans, and More!!!. Chronicle Books. ISBN 0811846660.

- Neil Zawacki (2004). The Villain's Guide to Better Living. Chronicle Books. ISBN 0811856666.