Refusenik: Difference between revisions

Angelmypal (talk | contribs) |

rv no consensus and unsourced POV addition; please discuss at the talk page per WP:CONSENSUS |

||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

Refuseniks included Jews who were desiring to emigrate on religious grounds and Jews seeking to immigrate to Israel for national/[[Zionism|Zionist]] aspirations and relatively secular Jews desired to escape an undercurrent of the state-sponsored anti-Semitism. Also, large numbers of [[Volga German]]s attempted to leave for [[Germany]], [[Armenians]] to join their [[diaspora]], [[evangelicalism|Evangelical]] [[Christian]]s, [[Roman Catholic]]s, and other ethnic and religious groups tried to escape persecutions or desired to seek a better life. |

Refuseniks included Jews who were desiring to emigrate on religious grounds and Jews seeking to immigrate to Israel for national/[[Zionism|Zionist]] aspirations and relatively secular Jews desired to escape an undercurrent of the state-sponsored anti-Semitism. Also, large numbers of [[Volga German]]s attempted to leave for [[Germany]], [[Armenians]] to join their [[diaspora]], [[evangelicalism|Evangelical]] [[Christian]]s, [[Roman Catholic]]s, and other ethnic and religious groups tried to escape persecutions or desired to seek a better life. |

||

The |

The coming to power of [[Mikhail Gorbachev]] in the Soviet Union in the mid-1980s and his policies of [[glasnost]] and [[perestroika]], as well as a desire for better relations with the West led to major changes. Most refuseniks were then allowed to emigrate. With the [[collapse of the Soviet Union]] at the end of the decade, the term "otkaznik" largely passed into history. |

||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

Revision as of 20:09, 25 November 2008

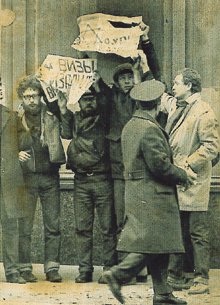

Refusenik (Hebrew: מסורב עליה, mesorav aliyah, "one who is not allowed to perform aliyah"; Russian: отказник, otkaznik, from "отказ", "refusal") was an unofficial term for individuals, typically but not exclusively Soviet Jews, who were denied permission to emigrate abroad by the authorities of the former Soviet Union and other countries of the Eastern bloc.[1] The term refusenik derived from the "refusal", handed down to a prospective emigrant from the Soviet authorities. Over time, "refusenik" has entered colloquial English usage for any type of protestor.

In 2008 filmaker Laura Bialis released a documentary film, "Refusenik", chronicling the human rights struggle of the Soviet refuseniks.[2]

History

A large number of Soviet Jews applied for exit visas to leave the Soviet Union, especially in the period following the 1967 Six-Day War. While some were allowed to leave, many were refused permission to emigrate, either instantly or their case could languish for years in the OVIR (ОВиР, "Отдел Виз и Регистрации", "Otdel Viz i Registratsii", English: Office of Visas and Registration), the MVD department responsible for provisioning of exit visas. In many instances, the reason was given that these persons had been given access at some point in their careers to information vital to Soviet national security and could not now be allowed to leave.[3]

During the Cold War, Soviet Jews were presumed a security liability or possible traitors[4]. To apply for an exit visa, the applicants (and sometimes their entire families) often had to quit their jobs, which in turn would make them vulnerable to charges of social parasitism, a criminal offense.[3]

Many Jews encountered institutional antisemitism which blocked their opportunities for advancement. Some government sectors were almost entirely off-limits to Jews[5][6]. In addition, Soviet restrictions on religious education and expression prevented Jews from engaging in Jewish cultural and religious life. While these restrictions led many Jews to seek to emigrate[7], requesting an exit visa was itself seen as an act of betrayal by Soviet authorities. Thus, prospective emigrants requested permission to emigrate at great risk, knowing that an official refusal would often be accompanied by dismissal from work and other forms of social ostracism and economic pressure.

A leading proponent and spokesman of the refusenik movement during the 1970s was Natan Sharansky. Sharansky's involvement with the Moscow Helsinki Monitoring Group helped to establish the struggle for emigration rights within the greater context of the human rights movement in the USSR. His arrest (on charges of espionage and treason) and trial contributed to international support for the refusenik cause.

Refuseniks included Jews who were desiring to emigrate on religious grounds and Jews seeking to immigrate to Israel for national/Zionist aspirations and relatively secular Jews desired to escape an undercurrent of the state-sponsored anti-Semitism. Also, large numbers of Volga Germans attempted to leave for Germany, Armenians to join their diaspora, Evangelical Christians, Roman Catholics, and other ethnic and religious groups tried to escape persecutions or desired to seek a better life.

The coming to power of Mikhail Gorbachev in the Soviet Union in the mid-1980s and his policies of glasnost and perestroika, as well as a desire for better relations with the West led to major changes. Most refuseniks were then allowed to emigrate. With the collapse of the Soviet Union at the end of the decade, the term "otkaznik" largely passed into history.

See also

- Aliyah from the Soviet Union and post-Soviet states

- The collapse of the Soviet Union and emigration to Israel

- Refusenik (disambiguation)

- Defection

- Lishkat Hakesher

- Jackson-Vanik amendment

- Balseros, Cuban citizens who are not allowed to migrate legally and cross to Florida in improvised boats.

- Refusenik (2008 film), a documentary about refuseniks

References

- ^ Mark Azbel' and Grace Pierce Forbes. Refusenik, trapped in the Soviet Union. Houghton Mifflin, 1981. ISBN 0395302269

- ^ The struggle behind the Iron Curtain. Philadelphia Daily News. June 27, 2008. Accessed June 28, 2008.

- ^ a b The Right to Emigrate, cont. Beyond the Pale. The History of Jews in Russia. Exhibit by Friends and Partners

- ^ Joseph Dunner. Anti-Jewish discrimination since the end of World War II. Case Studies on Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms: A World Survey. Vol. 1. Willem A. Veenhoven and Winifred Crum Ewing (Editors). Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. 1975. Hague. ISBN 90-247-1779-5, 90-247-1780-9; pages 69-82

- ^ Joseph Dunner. Anti-Jewish discrimination since the end of World War II. Case Studies on Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms: A World Survey. Vol. 1. Willem A. Veenhoven and Winifred Crum Ewing (Editors). Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. 1975. Hague. ISBN 90-247-1779-5, 90-247-1780-9; pages 69-82

- ^ Benjamin Pinkus. The Jews of the Soviet Union: the history of a national minority. Cambridge University Press, January 1990. ISBN-13: 9780521389266; pp. 229-230.

- ^ Boris Morozov (Editor). Documents on Soviet Jewish Emigration. Taylor & Francis, 1999. ISBN-13: 9780714649115

Further reading

- Natan Sharansky, Fear No Evil. The Classic Memoir of One Man's Triumph over a Police State. ISBN 1-891620-02-9.