Glass harmonica: Difference between revisions

m →Contemporary: change ref link to English site. |

|||

| Line 160: | Line 160: | ||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

* [http://www.glasharmonika.at/ Wiener Glasharmonika Duo, Information about the artists and the instruments] |

* [http://www.glasharmonika.at/ Wiener Glasharmonika Duo, Information about the artists and the instruments] |

||

* [http://www. |

* [http://www.thomasbloch.net Thomas Bloch's website, a prominent glassharmonica player (also ondes Martenot and cristal Baschet) - facts, videos, pictures, biography, discography, contact...] |

||

* [http://www.finkenbeiner.com/GLASSHARMONICA.htm G. Finkenbeiner Inc. site, manufacturer of glass harmonicas] |

* [http://www.finkenbeiner.com/GLASSHARMONICA.htm G. Finkenbeiner Inc. site, manufacturer of glass harmonicas] |

||

* [http://www.thebakken.org/exhibits/mesmer/glass-armonica.htm Display of glass armonica at The Bakken Library and Museum] |

* [http://www.thebakken.org/exhibits/mesmer/glass-armonica.htm Display of glass armonica at The Bakken Library and Museum] |

||

Revision as of 11:52, 14 January 2009

The glass harmonica, also known as the glass armonica, hydrocrystalophone, or simply armonica (derived from "harmonia", the Greek word for harmony), is a type of musical instrument that uses a series of glass bowls or goblets graduated in size to produce musical tones by means of friction (instruments of this type are known as friction idiophones).

Because its sounding portion is made of glass, the glass harmonica is a crystallophone. The phenomenon of rubbing a wet finger around the rim of a wine goblet to produce tones is documented back to Renaissance times; Galileo considered the phenomenon (in his Two New Sciences), as did Athanasius Kircher.

The Irish musician Richard Puckeridge is typically credited as the first to play an instrument composed of glass vessels by rubbing his fingers around the rims.[1] Beginning in the 1740s, he performed in London on a set of upright goblets filled with varying amounts of water. During the same decade, Christoph Willibald Gluck also attracted attention playing a similar instrument in England.

Names

The word "glass harmonica" (also glassharmonica, glass armonica, Armonica de verre in French, Glasharmonika in German) refers to any instrument played by rubbing glass or crystal goblets or bowls. When Benjamin Franklin invented his mechanical version of the instrument, he called it the armonica, based on the Italian word "armonia", which means "harmony".[2] The instrument consisting of a set of wine glasses (usually tuned with water) is generally known in English as "musical glasses" or "glass harp".

It can also be referred to as a "ghost fiddle".[citation needed]

The word hydrodaktulopsychicharmonica is also recorded, composed of Greek roots to mean something like "harmonica to produce music for the soul by fingers dipped in water" (hydro- for "water", daktul (daktyl) for "finger", psych- for "soul")[3] The Oxford Companion to Music mentions that this word is "the longest section of the Greek language ever attached to any musical instrument, for a reader of the The Times wrote to that paper in 1932 to say that in his youth he had heard a performance the advertisement of which styled the instrument the Hydrodaktulopsychicharmonica."[4] It is claimed that the Museum of Music in Paris displays a hydrodaktulopsychicharmonica.[5]

Benjamin Franklin's armonica

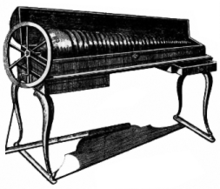

Benjamin Franklin invented a radically new arrangement of the glasses in 1761 after seeing water-filled wine glasses played by Edmund Delaval at Cambridge in England in 1758.[6] Franklin, who called his invention the "armonica" after the Italian word for harmony, worked with London glassblower Charles James to build one, and it had its world premiere in early 1762, played by Marianne Davies.

In Franklin's version, 37 bowls were mounted horizontally nested on an iron spindle. The whole spindle turned by means of a foot-operated treadle. The sound was produced by touching the rims of the bowls with moistened fingers. Rims were painted different colors according to the pitch of the note. A's were dark blue, B's purple, C's red, D's orange, E's yellow, F's green, G's blue, and accidentals white.[7] With the Franklin design it is possible to play ten glasses simultaneously if desired, a technique that is very difficult if not impossible to execute using upright goblets. Franklin also advocated the use of a small amount of powdered chalk on the fingers which helped produce a clear tone in the same way rosin is applied to the bows of string instruments.

Some attempted improvements on the armonica included adding keyboards, placing pads between the bowls to reduce vibration,[8] and using violin bows. These variations never caught on because they did not sound as pleasant.

Another supposed improvement was to have the glasses rotate into a trough of water. However, William Zeitler put this idea to the test by rotating an armonica cup into a basin of water: the water has the same effect as putting water in a wine glass — it changes the pitch. With several dozen glasses, each a different diameter and thus rotating with a different depth, the result would be musical cacophony.[9] It also made it much harder to make the glass speak, and muffled the sound.

In 1975, an original armonica was acquired by the Bakken Museum in Minneapolis, Minnesota and put on display.[10] It was purchased through a musical instrument dealer in France, from the descendants of Mme. Brillon de Jouy, a neighbor of Benjamin Franklin's from 1777 to 1785, when he lived in the Paris suburb of Passy.[10] Some 18th and 19th century specimens of the armonica have survived into the 21st century. Franz Mesmer also played the armonica and used it as an integral part of his Mesmerism.

An original Franklin armonica is on display at the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. This is also the home of the Benjamin Franklin National Memorial.[11]

Works

Mozart, Hasse, Carl Philipp Emmanuel Bach, Beethoven, Donizetti, Richard Strauss, and more than 100 composers composed works for the glass harmonica. Since it was rediscovered during the 1980s composers write again for it (solo, chamber music, opera, electronic music, popular music): Jan Erik Mikalsen, Regis Campo, Etienne Rolin, Philippe Sarde, Damon Albarn, Michel Redolfi, Cyril Morin, Stefano Giannotti,...

European monarchs indulged in it, and even Marie Antoinette had taken lessons on it as a child from Marianne Davies. One of the best known pieces is the Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy from the ballet The Nutcracker. Tchaikovsky's first draft called for glass harmonica, but he changed it to the newly-invented celesta before the work's premiere performance in 1892.[12] But it was probably dedicated to another instrument also called glassharmonica, invented a little bit later, which was a kind of glass xylophone. Saint-Saëns also used this percussive instrument in his "Carnaval des animaux" (in movements 7 and 14).

Purported dangers

The instrument's popularity did not last far beyond the 18th century. Some claim this was due to strange rumors that using the instrument caused both musicians and their listeners to go mad. (It is a matter of conjecture how pervasive that belief was; all the commonly cited examples of this rumor are German, if not confined to Vienna.) This was not true nor are the other superstitions listed below.

One example of fear from playing the glass harmonica was noted by a German musicologist Friedrich Rochlitz in Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung where it is stated that "the armonica excessively stimulates the nerves, plunges the player into a nagging depression and hence into a dark and melancholy mood that is apt method for slow self-annihilation. If you are suffering from any nervous disorder, you should not play it; if you are not yet ill you should not play it; if you are feeling melancholy you should not play it."

One armonica player, Marianne Kirchgessner died at the age of 39 of pneumonia or an illness much like it. See her obituary, written by her manager Heinrich Bossler in the Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung May 10, 1809. However, others, including Franklin, lived long lives. By 1820 the glass armonica had disappeared from public performance, perhaps because musical fashions were changing — music was moving out of the relatively small aristocratic halls of Mozart's day into the increasingly large concert halls of Beethoven and his successors, and the delicate sound of the armonica simply could not be heard. The harpsichord disappeared at about the same time — perhaps for the same reason.

A modern version of the "purported dangers" claims that players suffered lead poisoning because armonicas were made of lead glass. However, there is no known scientific basis for the theory that merely touching lead glass can cause lead poisoning. Furthermore, many modern versions, such as those made by Finkenbeiner, are made from pure silica glass.[13] It is known that lead poisoning was common in the 18th and early 19th centuries for both armonica players and non-players alike: doctors prescribed lead compounds for a long list of ailments, lead oxide was used as a preservative in food and beverages, food was cooked in tin/lead pots which gave off lead fumes--the tin protected the food, and acidic beverages were commonly drunk from lead pewter vessels. Even if armonica players of Franklin's day somehow received trace amounts of lead from their instruments, that would likely have been dwarfed by the lead they were receiving from other sources.[14]

Perception of the Armonica sound

The somewhat disorienting quality of the ethereal sound is due in part to the way that humans perceive and locate ranges of sounds. Above 4,000 Hertz we primarily use the volume of the sound to differentiate between each ear (left and right) and thus triangulate, or locate, the source. Below 1,000 Hertz we use the 'phase differences' of sound waves arriving at our ears to identify left and right for location. The predominant timbre of the armonica is in the range from 1,000-4,000 hertz, which coincides with the sound range where the brain is 'not quite sure' and thus we have difficulty locating it in space (where it comes from), and referencing the source of the sound (the materials and techniques used to produce it).[15]

Modern revival

Music for glass harmonica and glass harp was all-but-unknown from 1820 until the 1930s, when German virtuoso Bruno Hoffmann began reanimating interest in the glass harp repertoire with his stunning performances. Playing a standard "glass harp" (with real wine glasses in a box), he mastered almost all of the literature written for the instrument, and commissioned contemporary composers to write new pieces for it.

Franklin's glass armonica was re-invented by master glassblower and musician, Gerhard B. Finkenbeiner (1930–1999) in 1984. After thirty years of experimentation, Finkenbeiner's prototype consisted of clear glasses and glasses with gold bands. Those with gold bands indicate the equivalent of the black keys on the piano. Finkenbeiner Inc., of Waltham, Massachusetts, continues to produce these instruments commercially.

French instrument makers and artists Bernard and Francois Baschet invented a variation of the glass harmonica in 1952, the crystal organ or Cristal baschet, which consists of 52 chromatically-tuned glass rods that are rubbed with wet fingers. The main difference to the glass harmonica is that the rods, set horizontally, are attached to a heavy metal block to which the vibration is passed through a metal stem. The crystal organ is a fully acoustic instrument, and amplification is obtained using fiberglass cones fixed on wood and by a tall cut out metal part in the shape of a flame. Metallic rods resembling cat whiskers are placed under the instrument to increase the sound power of high-pitched sounds.

Notable armonica players

Historical

- Marie Antoinette

- Marianne Davies

- Benjamin Franklin (United States)

- Franz Mesmer

- Marianne Kirchgessner

- Mrs. Philip Thicknesse (born Anne Ford), 1775, United Kingdom)

- George Washington[citation needed] (United States)

Contemporary

- Thomas Bloch (France)

- Cecilia Gniewek Brauer,[16] Associate Member of Metropolitan Opera Orchestra since 1972, (United States)

- Martin Hilmer[17][18](Germany)

- Bruno Hoffmann (Germany)

- Dennis James (United States)

- Gloria Parker (United States) glass harp

- Gerald Schönfeldinger (Austria)[19]

- William Zeitler (United States)

Videos

- William Zeitler playing Adagio in C on the Armonica

- William Zeitler playing Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy

- A large choice of glassharmonica videos (solo, orchestra, chamber music from classical to pop music collaboration: Gorillaz, Tom Waits, Mozart, Sombach...) played by Thomas Bloch

Popular culture references

- The late stand-up comic Mitch Hedberg includes 'Coca-Cola in a glass harmonica' as an example of the extremely difficult-to-replace contents of hotel mini-bars.

- A Movie Broadway Danny Rose Directed by Woody Allen (film), a glass harmonica is played by Gloria Parker.

- Glass Harmonica player Dean Shostak played the instrument for a background piece for the Weather Channel.

- In the film Across The Universe the glass harmonica is used during the opening scene behind The Beatles song Girl.

- A short animation movie entitled "The glass harmonica" was directed by Andrei Khrjanovsky in 1968. It has been uploaded to YouTube: part 1 and part 2.

- The song "Airscape" on Robyn Hitchcock & the Egyptians' 1986 album Element of Light prominently features a glass harmonica played by keyboardist Roger Jackson.

- The instrument has been used in several film soundtracks, including Interview with the Vampire: The Vampire Chronicles, Mansfield Park, and the first original version March of the Penguins - La Marche de l'Empereur (performed by Thomas Bloch who also played Ondes Martenot and cristal Baschet with Damon Albarn / Gorillaz (Monkey: Journey to the West) Tom Waits / Marianne Faithfull / Bob Wilson (The Black Rider), Radiohead, Vanessa Paradis, in Amadeus by Milos Forman - long version, 2001 -...).

- As part of his role as Franz Mesmer in the 1994 movie Mesmer, Alan Rickman played the glass harmonica in several scenes.

- The main phrase to the album version of Björk's "All Neon Like" (Homogenic) is played on a glass harmonica.

- On MTV's airing of the special "Korn Unplugged", the song "Falling Away From Me" was set to the tune of a Glass Harmonica.

- The country group Trio consisting of Dolly Parton, Emmylou Harris, and Linda Ronstadt re-released a cover of "After the Gold Rush" by Neil Young. The re-released version, which appears on the group's 1998 album Trio 2, features the glass harmonica in the last part of the song, as well as in the video.

- The glass harmonica is featured on Mister Rogers' Neighborhood #1764. It is played by Dean Shostak.

- The glass harmonica is featured on the movie "Cutter's Way" composed by Jack Nitzsche and played by Eric Harry.

- In an episode of the Simpsons, Hugh Hefner plays Peter and the Wolf on a glass harmonica.

- Glass harmonica was used by Elliot Goldenthal in the soundtrack of Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within

- Tom Waits used several Glass Harmonicas in the song "Rainbirds" from the album Swordfishtrombones.

- Peter Griffin plays a glass armonica in an episode of Family Guy

Literary references

- In his novel Mason & Dixon Thomas Pynchon fictionally describes Franklin's armonica: "If Chimes could whisper, if Melodies could pass away, and their souls wander the Earth... if Ghosts danced at Ghost Ridottoes, 'twould require such Musick, Sentiment ever held back, ever at the edge of breaking forth, in Fragments, as Glass breaks."

- In the manga and anime D.N.Angel, a living painting of a unicorn would constantly kidnap little girls to be playmates of the girl inside of the artwork. Whenever it arrived, the sound of a glass harmonica playing would be heard.

- In Bruce Sterling's short story "We See Things Differently" (published in Semiotext(e) SF, 1989, and collected in his own collection, Globalhead, as well as The Norton Book of Science Fiction), the near-future rock musician/insurrectionary Tom Boston plays it in concert: "...legend said that its players went mad, their nerves shredded by its clarity of sound. It was a legend Boston was careful to exploit. He played the machine sparingly, with the air of a magician, of a Solomon unbottling demons. I was glad of his spare use, for its sound was so beautiful that it stung the brain."

- The novel The Glass Harmonica by Louise Marley is speculative/historical fiction focusing on the glass harmonica. It describes Benjamin Franklin's invention of the armonica, the public debut of the armonica as played by Marianne Davies, and exposure of a young Mozart to the instrument. A future story arc describes the modern revival of the instrument and the superstitions regarding its potential effects on the nerves..

See also

References

Footnotes

- ^ Bloch, Thomas, http://www.finkenbeiner.com/gh.html, retrieved 2007-05-22

{{citation}}: External link in|title= - ^ The free reed wind instrument called the harmonica was not invented until 1821, sixty years later.

- ^ Ian Crofton (2006) "Brewer's Cabinet of Curiosities", ISBN 0304368016

- ^ As quoted from the 1970 edition of the Companion by a Glasssharmonica.com webpage

- ^ "Museums celebrate spring" Template:Fr icon

- ^ Downloadable Broadcast on BBC Radio 4 Adam Hart Davis on the Angelic Organ of Evil

- ^ The Writings of Benjamin Franklin, Volume III: London, 1757 - 1775 - Faults in Songs

- ^ Zeitler, William, The Music and the Magic of the Glass Armonica, retrieved 2007-05-22

- ^ See http://www.glassarmonica.com/armonica/history/franklin/WaterTrough.php which includes a video demonstration.

- ^ a b The Bakken, Glass Armonica, retrieved 2007-05-22

- ^ The Franklin Institute - Exhibit - Franklin... He's Electric

- ^ Sterki, P. (2000); Klingende Gläser; Peter Lang; NY; ISBN 3906764605, p. 97

- ^ Glass harmonica at Finkenbeiner

- ^ See Finger, Stanley (2006); Doctor Franklin's Medicine; U of Pennsylvania Press; Philadelphia; ISBN 081223913X. Chapter 11, "The Perils of Lead" (p.181-198) discusses the pervasiveness of lead poisoning in Franklin's day and Franklin's own leadership in combating it.

- ^ Dr Nicky Gibbon, Sheffield Hallam University, on BBC Radio 4 - Angelic Organ of Evil

- ^ Photograph of Armonica and Cecilia Gniewek Brauer at Gigmasters

- ^ Glassmusic with verrophone and glassharp

- ^ The Glassharmonica made by Sascha Reckert

- ^ [1]

Notations

- "An Extensive Bibliography". of resources about the armonica.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "Franklin, Benjamin". Franklibn correspondence regarding the armonica.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "Galileo, Galilei". Passage from 'Two New Sciences' by Galileo about the 'wet finger around the wine glass' phenomenon (1638).

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "wiseGEEK". What is a Glass Harmonica?.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - King, A.H., "The Musical Glasses and Glass Harmonica", Royal Musical Association, Proceedings, Vol.72, (1945/1946), pp.97-122.

- Sterki, Peter. Klingende Gläser. Bern. NY 2000. ISBN 3-906764-60-5 br.

- History of the Glass Harmonica

- The Glass Harmonica: Stairway to Madness

Instruction books

- Bartl. About the Keyed Armonica.

- Ford, Anne (1761). Instructions for playing on the music glasses (Method). London. "A pdf copy" (PDF).

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - Franklin, J. E. Introduction to the Knowledge of the Seraphim or Musical Glasses.

- Hopkinson-Smith, Francis (1825). Tutor for the Grand Harmonicon. Baltimore, Maryland.

- Ironmonger, David. Instructions for the Double and Single Harmonicon Glasses.

- Muller, Johann Christian (aka John Christopher Moller). Anleitung zum Selbstunterricht auf der Harmonika.

- Roellig, Leopold. Uber die Harmonika / Uber die Orphika.

- Smith, James. Tutor for the Musical Glasses.

- Wunsch, J. D. Practische - Schule fur die lange Harmonika.

External links

- Wiener Glasharmonika Duo, Information about the artists and the instruments

- Thomas Bloch's website, a prominent glassharmonica player (also ondes Martenot and cristal Baschet) - facts, videos, pictures, biography, discography, contact...

- G. Finkenbeiner Inc. site, manufacturer of glass harmonicas

- Display of glass armonica at The Bakken Library and Museum

- Hear the Glass Armonica History, articles, www.crystalisa.com

- Articles (with citations) about the armonica by William Zeitler, www.glassarmonica.com, free MP3 and videos.

- 'The Glass Harmonica' A history by Thomas Bloch

- Play the armonica Interactive version of playing the armonica.

- The World of Glass Music

- bizbash Water Glasses

- Hear excerpt from Weeps and Ghosts for Glass Harmonica and String Quartet by Jan Erik Mikalsen. New piece dedicated to and performed by Thomas Bloch.

- Dennis James interview