In Flanders Fields: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 203.52.140.58 (talk) to last revision by Tide rolls (HG) |

→Poem: fix apparent vandalism |

||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

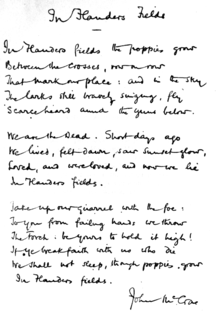

[[File:In Flanders fields and other poems, handwritten.png|thumb|An autograph copy]] |

[[File:In Flanders fields and other poems, handwritten.png|thumb|An autograph copy]] |

||

The title piece of ''In Flanders Fields and Other Poems'', 1919, was printed as:<ref name="Macphail 1919"/> |

The title piece of ''In Flanders Fields and Other Poems'', 1919, was printed as:<ref name="Macphail 1919"/> |

||

<poem>In Flanders fields the poppies |

<poem>In Flanders fields the poppies grow |

||

Between the crosses, row on row, |

Between the crosses, row on row, |

||

That mark our place; and in the sky |

That mark our place; and in the sky |

||

Revision as of 22:07, 17 September 2010

"In Flanders Fields" is one of the most notable poems written during World War I, created in the form of a French rondeau. It has been called "the most popular poem" produced during that period.[1] Canadian physician and Lieutenant Colonel John McCrae wrote it on 3 May 1915 (see 1915 in poetry), after he witnessed the death of his friend, Lieutenant Alexis Helmer, 22 years old, the day before. The poem was first published on 8 December of that year in the London-based magazine Punch.

Historical context

The poppies referred to in the poem grew in profusion in Flanders in the disturbed earth of the battlefields and cemeteries where war casualties were buried[2] and thus became a symbol of Remembrance Day. The poem is often part of Remembrance Day solemnities in Allied countries which contributed troops to World War I, particularly in countries of the British Empire that did so.

The poem "In Flanders Fields" was written after John McCrae witnessed the death, and presided over the funeral, of a friend, Lt. Alexis Helmer. By most accounts it was written in his notebook[3] and later rejected by McCrae. Ripped out of his notebook, it was rescued by a fellow officer, Francis Alexander Scrimger, and later published in Punch magazine. However, this story is rejected by the editor at the time:

"A legend has already grown up around the publication of "In Flanders Fields" in Punch. The truth is, 'that the poem was offered in the usual way and accepted; that is all.' The usual way of offering a piece to an editor is to put it in an envelope with a postage stamp outside to carry it there, and a stamp inside to carry it back. Nothing else helps."[4]

Poem

The title piece of In Flanders Fields and Other Poems, 1919, was printed as:[4]

In Flanders fields the poppies grow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the Dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved, and were loved, and now we lie

In Flanders fields.

Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.

Status

In 1918 US professor Moina Michael, inspired by the poem, published a poem of her own in response, called We Shall Keep the Faith.[5] In tribute to the opening lines of McCrae's poem — "In Flanders fields the poppies blow / Between the crosses row on row," — Michael vowed to always wear a red poppy as a symbol of remembrance for those who served in the war.[6]

The poem has achieved near-mythical status in contemporary Canada and is one of the nation's most prominent symbols. Most Remembrance Day ceremonies will feature a reading of the poem in some form (it is also sung a cappella in some places), and some Canadian school children memorize the verse. The poem is part of Remembrance Day ceremonies in the United Kingdom, where it holds as one of the nation's best-loved, and is occasionally featured in Memorial Day ceremonies in the United States.[citation needed]

A portion of the poem is now printed on Canadian $10 notes, where it spawned a rumour that the poem had been misprinted, resulting from popular confusion between the first line's "blow" and the penultimate line's "grow."[citation needed]

Schools in Guelph (McCrae's birthplace) once taught that "the poppies grow" could refer to spreading blood stains on the shallow graves.[citation needed]

The use of "grow" in the first line appears in a handwritten and autographed copy for the 1919 edition of McCrae's poems; the editor, Andrew Macphail, notes in the caption, "This was probably written from memory as "grow" is used in place of "blow" in the first line." [4] However, a tracing of a holograph copy on the letterhead of Captain Gilbert Tyndale-Lea M.C. now held by the Imperial War Museum claims that the original dates from 29 April 1915 and that it was given to the captain by the poet on that date. This clearly shows 'grow' in the first line and would change the publicly-held belief as to its date of composition and original first line.[7] This was certainly changed by the time he submitted it to Punch for publication in December of that year. The truth of whether McCrae originally wrote 'grow' or 'blow' in the first line will most likely never clearly be established.

Criticisms

Critic Paul Fussell, in The Great War and Modern Memory, pointed out the sharp distinctions between the pastoral, sacrificial tone of the poem's first nine lines and the "recruiting-poster rhetoric" of the poem's third stanza; Fussell said the poem, appearing in 1915, would serve to denigrate any negotiated peace which would end the war, and called these lines "a propaganda argument," saying "words like vicious and stupid would not seem to go too far."[8] Modern public readings of the poem, however, stress the debt to the dead and the necessity to honour their memory in ceremonies often focusing on the sacrifice and sorrow of war.[citation needed]

Other versions

An illustrated edition of the poem was published in 1921, with a preface by William Thomas Manning.[9]

An official adaptation into French, used by the Canadian government in Remembrance Day ceremonies, was written by Jean Pariseau and is entitled Au champ d'honneur.[citation needed]

In popular culture

An episode of The Simpsons called "When Flanders Failed" (#38–3) is an implicit reference to this poem. In the audio commentary to this episode which was recorded in 2003 Matt Groening, Al Jean, Mike Reiss, Jon Vitti and Jim Reardon talk about writer Jeff Martin who came up with this "World War I reference which no one ever gets".

The song "We Are the Lost" by the group Libera paraphrases this poem along with For the Fallen, sung as a choral hymn. The poem is referenced by Mort Shuman in his translation of the song "Marieke" by Jacques Brel as well as by Siouxsie and the Banshees in "Poppy Day" from their second LP "Join Hands". The song was adapted as the song "Flanders Fields" by The Escalators on their 1983 album "Moving Staircases" and also Big Head Todd and the Monsters on their 1989 debut album "Another Mayberry". The Guess Who parody the song in Friends of Mine.

In the TV special What Have We Learned, Charlie Brown?, Linus recites the poem while standing in front of the remnants of a battlefield in Ypres, including the British aid station where McCrae was inspired to write the poem.

The poem is referenced in the film Mr. Holland's Opus and Herman Wouk's novel City Boy.

The line "To you from failing hands we throw The torch; be yours to hold it high" is written on the wall of the Montreal Canadiens' dressing room. It is also inscribed upon the base of the flagpole at the American Cemetery, Madingley, Cambridge UK.

"The Piper" written by the fictional Walter Blythe in L. M. Montgomery's Rilla of Ingleside is a tribute to In Flanders Field in content and form as well as Walter's Canadian nationality.

In an episode of Marcus Welby, M.D., a broken-down director has an unfinished script entitled "Flanders' Field". It was unfinished because during the writing of this anti-war film, Pearl Harbor was attacked. A young film student helps the director (while Welby heals him physically) complete the film to accolades.

Notes

- ^ Paul Fussell, The Great War and Modern Memory, Oxford University Press, 2000, p. 248.

- ^ The tendency of red poppies to grow on the fresh graves of soldiers in the fields of northern Europe has been noted at least from Napoleonic times. See The History and Poetry of "In Flanders Fields".

- ^ Arlingtoncemetery.net

- ^ a b c Macphail, Andrew (1919). "John McCrae: An essay in character". In Flanders Fields and Other Poems.

- ^ "Moina Michael". Digital Library of Georgia/University of Georgia. Retrieved 2009-02-18.

- ^ "Where did the idea to sell poppies come from?". BBC News. 10 November 2006. Retrieved 2009-02-18.

- ^ First World War Poetry Archive, http://www.oucs.ox.ac.uk/ww1lit/collections/item/1643 c.f. Imperial War Museum Record

- ^ Fussell, pp. 249-250.

- ^ McCrae, John (1921). In Flanders Fields. William Thomas Manning, Ernest Clegg (illustrations) (limited edition ed.). William Edwin Rudge.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help)

External links

- Free audiobook from LibriVox

- This site contains an account of the writing of the poem and a facsimile of the author's manuscript.

- In Flanders Fields, the website of the museum of this name in Ypres, dedicated to this poem

- Royal Canadian Legion web page about John McCrae, In Flanders Fields, and the custom of wearing poppies

- In Flanders Fields, setting by Canadian composer Michael Roberts

- In Flanders Fields, new musical interpretation by award winning Canadian songwriter Jon Brooks, released on May 3, 2007

- In Flanders Fields, choral piece by composer Bradley Nelson, commissioned by Fresno State Chamber Singers and Chico State Chamber Singers of California State University

- Lost Poets of the Great War, a hypertext document on the poetry of World War I by Harry Rusche, of the English Department, Emory University, Atlanta Georgia. It contains a bibliography of related materials.