Dragon Quest (video game): Difference between revisions

Reverted 1 edit by 74.129.161.248 (talk); The names were changed in the remakes. (TW) |

→Development and release: elaborated |

||

| (2 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 46: | Line 46: | ||

==Development and release== |

==Development and release== |

||

''Dragon Quest'' was |

[[Yuji Horii]] and his team at [[Chunsoft]] began production on ''Dragon Quest'' in 1985.<ref name=Dragon-Warrior>[http://www.1up.com/do/feature?cId=3133890 Dragon Warrior], [[1UP]]</ref> It was eventually released in Japan on May 26, [[1986 in video gaming|1986]], for the [[Famicom]].<ref name="DW GameFAQs">{{cite web|url=http://www.gamefaqs.com/console/nes/data/563408.html|title=Dragon Warrior Release Information for NES|publisher=GameFAQs|accessdate=2009-10-09}}</ref> Designer [[Yuji Horii]] created ''Dragon Quest'' to introduce the concept of role-playing video games, previously limited to a niche computer audience, to a much wider audience in Japan.<ref name="Iwata Asks: History">{{cite web|url=http://dqnine.com/#/iwata/|title=Dragon Quest: Sential of the Starry Skies|work=Iwata Asks|publisher=Square-Enix|at=The History of Dragon Quest|accessdate=2010-12-05}}</ref> He has cited western RPGs like ''[[Wizardry]]'' and ''[[Ultima (series)|Ultima]]'' as inspiration for ''Dragon Quest's'' gameplay,<ref name="EGM"/><ref name="np238_84" /> specifically the first-person [[Random encounter|random battles]] in ''Wizardry'' and the overhead movement in ''[[Ultima I: The First Age of Darkness|Ultima]]''.<ref>Kurt Kalata, [http://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/3520/the_history_of_dragon_quest.php The History of Dragon Quest], [[Gamasutra]]</ref> Another influence was his own 1983 [[visual novel]] game ''[[Portopia Renzoku Satsujin Jiken|Portopia Serial Murder Case]]'', specifically the mystery puzzle and storytelling aspects.<ref name=Gotemba-Iwamoto>Goro Gotemba & Yoshiyuki Iwamoto (2006), ''Japan on the upswing: why the bubble burst and Japan's economic renewal'', [http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=eGA9qByeQH0C&pg=PA201&lpg=PA201 p. 201], Algora Publishing, ISBN 0875864627</ref> |

||

Horii's intention behind ''Dragon Quest'' was to create a RPG that appeals to a wider audience unfamiliar with the genre or video games in general. This required the creation of a new kind of RPG, that didn't rely on previous ''[[Dungeons & Dragons|D&D]]'' experience, didn't require hundreds of hours of rote fighting, and that could appeal to any kind of gamer.<ref name=Dragon-Warrior/> Compared to statistics-heavy computer RPGs, ''Dragon Quest'' was a more streamlined, faster-paced game based on exploration and combat, and featured a [[Top-down perspective|top-down view]] in dungeons, in contrast to the [[First person (video games)|first-person view]] used for dungeons in earlier computer RPGs.<ref name="mobyoleg_168">{{Harvnb|Oleg|p="Brief History of Japanese RPGs"|Ref=mobyoleg}}</ref> The game also placed a greater emphasis on storytelling and emotional involvement,<ref name="npinterview">{{cite book |editor=|title=Nintendo Power volume 221 |year=2007 |publisher=[[Future US]]|isbn=|pages=78–80|quote=At the time I first made ''Dragon Quest'', computer and video game RPGs were still very much in the realm of hardcore fans and not very accessible to other players. So I decided to create a system that was easy to understand and emotionally involving, and then placed my story within that framework.}}</ref> building on Horii's previous work ''Portopia Serial Murder Case'', but this time introducing a [[coming of age]] tale for ''Dragon Quest'' that audiences could relate to, making use of the RPG level-building gameplay as a way to represent this.<ref name=Gotemba-Iwamoto/> It also featured elements still found in most console RPGs, like major quests interwoven with minor subquests and an incremental spell system,<ref name="gspot_consolehist_a">{{Harvnb|Vestal|1998a|p="Dragon Quest"|Ref=gspot_consolehist}}</ref> alongside [[anime]]-style art by [[Akira Toriyama]] and a classical score by [[Koichi Sugiyama]] that was considered revolutionary for console gaming.<ref name=Dragon-Warrior/> |

|||

Horii was aware of the high learning curve role-playing video games had as a comparison to other video games at the time. To compensate for this, ''Dragon Warrior'' has quick level up at the start and gave the player a clear final goal which was visable the first time the player goes to the world map: the Dragon Lord's castle.<ref name="Iwata Asks: History"/> |

|||

Horii believed the [[Famicom]] system the ideal venue as unlike [[arcade game]]s, the player did not have to worry about spending money if they got a [[game over]]. In addition, the player continued playing from where they left off before. Due to memory constraints, Dragon Warrior was forced to use just one [[player character]] even though Horii wanted to use more.<ref name="Iwata Asks: History"/> Horii was aware of the high learning curve role-playing video games had as a comparison to other video games at the time. To compensate for this, ''Dragon Warrior'' has quick level up at the start and gave the player a clear final goal which was visable the first time the player goes to the world map: the Dragon Lord's castle.<ref name="Iwata Asks: History"/> The game also gave players a series of smaller scenarios to build up the player's strength in order to achieve that objective.<ref name="Iwata Asks: History"/> The gameplay itself was [[Nonlinear gameplay|non-linear]], with most of the game not blocked in any way other than by being infested with monsters that can easily kill an unprepared player. This was balanced by the use of bridges to signify a change in difficulty and a level progression that starts at a high growth rate, with the effective rate of character growth decelerating over time, in contrast to the early editions of ''D&D'' which had random initial stats and a constant rate of growth, though more recent editions of ''D&D'' have balanced the level progression in a similar manner.<ref name=DQ-III>[http://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/1902/game_design_essentials_20_open_.php?page=8 20 Open World Games: Dragon Quest III, a.k.a. Dragon Warrior III], [[Gamasutra]]</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | The series has been released on multiple platforms since its initial release including in Japan in 2004 as a generic [[cell phone]] game with updated graphics that are similar to those of ''[[Dragon Quest VI: Realms of Reverie|Dragon Quest VI]]''.<ref>{{cite web | year=2004 | title=Dragon Quest for Mobile Phones | url=http://www.gamespot.com/mobile/rpg/dragonquest/index.html| accessdate=2007-10-14}}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | The ''Dragon Quest'' series has been released on multiple platforms since its initial release including in Japan in 2004 as a generic [[cell phone]] game with updated graphics that are similar to those of ''[[Dragon Quest VI: Realms of Reverie|Dragon Quest VI]]''.<ref>{{cite web | year=2004 | title=Dragon Quest for Mobile Phones | url=http://www.gamespot.com/mobile/rpg/dragonquest/index.html| accessdate=2007-10-14}}</ref> |

||

===North American localization=== |

===North American localization=== |

||

Revision as of 15:47, 18 January 2011

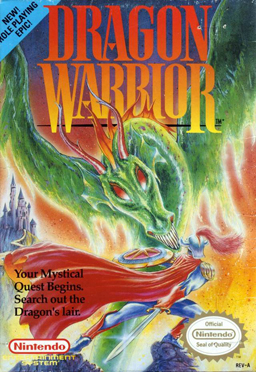

| Dragon Warrior | |

|---|---|

Box art | |

| Developer(s) | Chunsoft |

| Designer(s) | Yūji Horii Koichi Nakamura Yukinobu Chida |

| Artist(s) | Akira Toriyama |

| Composer(s) | Koichi Sugiyama |

| Series | Dragon Quest |

| Platform(s) | NES/Family Computer, MSX, NEC PC-9801, Sharp X68000 Super Famicom, Game Boy/Game Boy Color (hybrid cartridge), Mobile phone |

| Genre(s) | Console role-playing game |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

Dragon Warrior, known as Dragon Quest (ドラゴンクエスト, Doragon Kuesuto) in Japan, is a console role-playing game developed by Chunsoft and published in Japan by Enix (now Square Enix) in 1986 for the Nintendo Entertainment System.[1] Dragon Warrior has been ported and remade for several platforms including the MSX, Super Famicom, Game Boy Color, and mobile phones.

It is the inaugural game in Enix's flagship Dragon Quest series, which was known as the Dragon Warrior series in North America until 2003 due to a trademark conflict with the role-playing game (RPG) DragonQuest and TSR, Inc. (later Wizards of the Coast).[n 1][2]

Dragon Warrior was one of the first exposures to console RPGs for gamers in the US when it was released. Its effects on the console RPG genre have been considered to be above and beyond that of the more widely recognized, in the West, title of Final Fantasy.

Gameplay

Dragon Warrior uses console role-playing game mechanics which were described by Kurt Kalata of Gamasutra as archaic in 2008.[3] The player takes the role of a namable Hero. The Hero's name has an effect on his statistical growth over the course of the game.[4] Battles are fought in a turn-based format and experience points and gold are awarded after every battle, allowing the Hero to level-up in ability and allows them to buy better weapons, armor, and items. Progression consists of traveling over an overworld map and through dungeons, fighting monsters encountered via random battles along the journey.[5]

Synopsis

Plot

Although this is the first title released of the Dragon Warrior franchise, this game is actually the second, chronologically, of a three game series which share a storyline. The story is preceded by that of Dragon Warrior III and followed by Dragon Warrior II.[6]

The protagonist of the story is a warrior who is a descendent of the legendary hero Erdrick (known as Loto in remakes). Starting in the chambers of King Lorik in Tantegel Castle, the player is made aware that the Dragonlord has stolen the Ball of Light which must be reclaimed to restore peace to the land. The princess, Gwaelin (known as Lora in remakes), has also been kidnapped, and is now held by a dragon in a distant cave.

Although this minimalistic story presents itself at the beginning, the player will find more minor story elements to the game as it progresses. These mostly occur through dialogues with non-player characters that detail rescuing the Princess Gwaelin, the destruction of the town of Hauksness, and the hints about relics needed to reach the Dragonlord. Once the Hero rescues Gwaelin, she falls in love with him and aids him in finding all the necessary items in order to reach the Dragonlord's castle. As the hero collects the final items, a Rainbow Bridge appears for the Hero to cross finally entering the Dragonlord's castle. After fighting his way through the castle and retrieving one last relic, the Hero confronts the Dragonlord. At this point the hero is given the choice to side with the Dragonlord or fight him. If the player chooses the former, the game ends with the implication that together with the Dragonlord the Hero enslaves the world. If the player refuses, the Hero fights and ultimately defeats the Dragonlord, bringing peace to the land. After returning to Tantegel Castle, the Hero sets off with Gwaelin across the ocean where their fate is ultimately revealed in the sequel, Dragon Warrior II.

Characters

Dragon Warrior consists of only a few notable characters; the Hero and the Dragonlord are the two main characters. Others major supporting characters include: King Lorik, his daughter, Princess Gwaelin, and the sages the Hero meets along his journey.[5]

Little is known about the Hero besides his ancestry, being a descendant of the legendary Erdrick.[7][8][9] The only hints of personality for the character are a relationship with Princess Gwaelin and the yes-or-no answers the player can select to certain questions proposed by certain characters throughout the game. The player can name him however he or she wishes, within the limits of the naming system (eight letters in the North American NES version,[5] four hiragana characters in the Japanese Famicom version).[10]

The Dragonlord is a dragon from Charlock whose soul became evil from learning magic.[11] He sought "unlimited power and destruction,"[11] which resulted in a rising tide of evil throughout Alefgard. He rules from Charlock Castle[7][8] to the southeast of Tantegel Castle and the starting point of the game. There, surrounding swamps and a destroyed bridge to the mainland have rendered it inaccessible. Inside the castle, monsters and a complex maze of turns further protects his throne.[8] The Dragonlord's motive is to enslave the world with his army of monsters.[5]

Development and release

Yuji Horii and his team at Chunsoft began production on Dragon Quest in 1985.[12] It was eventually released in Japan on May 26, 1986, for the Famicom.[13] Designer Yuji Horii created Dragon Quest to introduce the concept of role-playing video games, previously limited to a niche computer audience, to a much wider audience in Japan.[14] He has cited western RPGs like Wizardry and Ultima as inspiration for Dragon Quest's gameplay,[1][15] specifically the first-person random battles in Wizardry and the overhead movement in Ultima.[16] Another influence was his own 1983 visual novel game Portopia Serial Murder Case, specifically the mystery puzzle and storytelling aspects.[17]

Horii's intention behind Dragon Quest was to create a RPG that appeals to a wider audience unfamiliar with the genre or video games in general. This required the creation of a new kind of RPG, that didn't rely on previous D&D experience, didn't require hundreds of hours of rote fighting, and that could appeal to any kind of gamer.[12] Compared to statistics-heavy computer RPGs, Dragon Quest was a more streamlined, faster-paced game based on exploration and combat, and featured a top-down view in dungeons, in contrast to the first-person view used for dungeons in earlier computer RPGs.[18] The game also placed a greater emphasis on storytelling and emotional involvement,[19] building on Horii's previous work Portopia Serial Murder Case, but this time introducing a coming of age tale for Dragon Quest that audiences could relate to, making use of the RPG level-building gameplay as a way to represent this.[17] It also featured elements still found in most console RPGs, like major quests interwoven with minor subquests and an incremental spell system,[20] alongside anime-style art by Akira Toriyama and a classical score by Koichi Sugiyama that was considered revolutionary for console gaming.[12]

Horii believed the Famicom system the ideal venue as unlike arcade games, the player did not have to worry about spending money if they got a game over. In addition, the player continued playing from where they left off before. Due to memory constraints, Dragon Warrior was forced to use just one player character even though Horii wanted to use more.[14] Horii was aware of the high learning curve role-playing video games had as a comparison to other video games at the time. To compensate for this, Dragon Warrior has quick level up at the start and gave the player a clear final goal which was visable the first time the player goes to the world map: the Dragon Lord's castle.[14] The game also gave players a series of smaller scenarios to build up the player's strength in order to achieve that objective.[14] The gameplay itself was non-linear, with most of the game not blocked in any way other than by being infested with monsters that can easily kill an unprepared player. This was balanced by the use of bridges to signify a change in difficulty and a level progression that starts at a high growth rate, with the effective rate of character growth decelerating over time, in contrast to the early editions of D&D which had random initial stats and a constant rate of growth, though more recent editions of D&D have balanced the level progression in a similar manner.[21]

The Dragon Quest series has been released on multiple platforms since its initial release including in Japan in 2004 as a generic cell phone game with updated graphics that are similar to those of Dragon Quest VI.[22]

North American localization

The game was localized for the North America release in August 1989,[13] but the title is changed to Dragon Warrior to avoid infringing on the trademark of the pen and paper role-playing game DragonQuest,[15] although there was another pen-and-paper role-playing system called Dragon Warriors. Because the game was released in North America nearly three years after the original Japanese version, the graphics were improved so as to make it look more up-to-date. It also featured a battery-backed RAM savegame, whereas the Japanese version used lengthy passwords with kana characters.[3] Other differences included revised sprites for the US version, which face in their direction of travel. In the original Japanese versions, the sprites were smaller and only faced forward, and players had to choose which direction they acted in from a menu. Also, spells were given self-explanatory one-word titles, as opposed to the made-up words in the Japanese version. Locations were renamed and in-game dialogue was rewritten in a pseudo medieval English style.[15] The town in which the Hero must first buy keys features a woman who now offers to sell tomatoes rather than the sexually-explicit "puff-puff" she and her "maidens" offer in the Japanese version.[3] [23]The English dialogue and graphics improvements caused the game to reach 1 megabit in size (128 kilobytes), twice the size of the Japanese version, which was 512 kilobits (64 kilobytes). Nintendo released the game in North America themselves, as Enix had no operations outside of Japan.

Nintendo Power provided three feature articles on Dragon Warrior from May/June 1989 - Sept/Oct 1989.[24][25][26] The Nov/Dec 1989 issue provided a Strategy Guide.[27] In March/April 1990, the magazine provided a map/poster of Dragon Warrior/Super C, and it featured a Dragon Warrior text adventure.[28] During that year, Nintendo Power gave away free copies of Dragon Warrior to subscribers, along with a card explaining the equipment, monsters, levels, and locations. Brief mention of the subscription bonus is made in Vol. 80 of Nintendo Power.[29]This has resulted in Dragon Warrior being one of the most common games made for the NES.

Super Famicom

Dragon Quest, along with Dragon Quest II, was remade as a one cartridge compilation known as Dragon Quest I & II for the Super Famicom on December 18, 1993.[30] This remake was marketed exclusively in Japan (due to the absence of Enix America Corporation),[original research?] and was changed from the original, which included enhanced graphics and sound, as well as enhancements in their game: a vault added in Mercado; a wandering item salesman added in Rimuldar; the Flame Sword usable as an item in battle; the ability to save the game as in the North American release; and some monsters (Dragon guarding Laura and the Golem guarding Mercado) had their HP and rewards increased.[31]

This remake has since been unofficially translated into English and Brazilian Portuguese by the online fan translation group RPG-One in 2002. Like the Game Boy Color version, the Early Modern English language was not used in the unofficial translation.[32]

BS Dragon Quest was also released for the Satellaview extension for the Super Famicom exclusively in Japan in 1998.[33] This game is based on the Super Famicom remake of Dragon Quest. In this game, players would download a portion of the game over the period of a month.[34] There would be special quests taken from the original game, which needed to be completed in a certain time period. This game included tiny medal collection as a new feature from previous releases.[35]

Game Boy Color

The Game Boy Color September 2000 release of Dragon Warrior I + II in North America, was based on the Super Famicom release of Dragon Quest I + II.[36] It used an entirely new translation, discarding the Elizabethan English style and giving names closer to the Japanese version's.[37][n 2] In this remake Dragonlord's name was changed to DracoLord, and Erdrick was changed to Loto.[38] Several conveniences were added, such as a quick-save feature and a streamlined menu system. Monsters yield more experience and gold after being defeated to reduce the amount of time needed to raise levels and save up for purchases.[38]

References in the Final Fantasy series

In the United States Erdrick was referenced as early as the original NES Final Fantasy, where one of the tombstones in Elfland says "Here lies Erdrick." (The Japanese version read, "Here lies Link", a reference to the Legend of Zelda series main character.) Next, Loto's Sword is used during an optional boss fight against Gilgamesh in Final Fantasy XII. This also marks the first time the mix of Final Fantasy and Dragon Quest has happened in the light of both Square and Enix merging, except for Itadaki Street.

Related media

Dragon Warrior has spawned some related media, notably a manga series and a symphonic video game soundtrack.

Manga

The manga series, Dragon Quest Retsuden: Roto no Monshō (ドラゴンクエスト列伝 ロトの紋章, Dragon Quest Saga: Roto's Emblem), was written by Chiaki Kawamata and Junji Koyanagi with artwork by Kamui Fujiwara and was published in Monthly Shōnen Gangan from 1991 through 1997.[39] The series was later compiled into for 21 volumes published by Enix;[40] in 1994 it was released on CD and was released on December 11, 2009 on the PlayStation Portable as part of manga distribution library.[41] In 1996 an anime movie based on the manga was released on video cassette.[42] A sequel series, Dragon Quest Retsuden: Roto no Monshō ~Monshō o Tsugumono-tachi e~ (ドラゴンクエスト列伝 ロトの紋章 ~紋章を継ぐ者達へ~, Dragon Quest Retsuden: Roto no Monshō - To the Children Who Inherit the Emblem), published by Square-Enix started in 2005 and is still ongoing; nine volumes have been released.[43] The first four volumes were written by Jun Eishima and the last five volumes written by Takashi Umemura. All of them have been supervised by Yuji Horii with artwork done by Kamui Fujiwara.[44]

Dragon Quest Retsuden: Roto no Monshō is meant to take place between Dragon Warrior III and Dragon Warrior. After monsters possessed the Carmen's king for seven years, the kingdom fell to the hordes of evil. The only survivors were Prince Arus and an army General's daughter, Lunafrea. Meanwhile, in the Kingdom of Loran, a child is born and named Jagan per the orders of Demon Lord, Imagine. As Loto's descendant, Arus, along with Lunafrea, set out to defeat the monsters and restore peace to the world.

Dragon Quest Retsuden: Roto no Monshō ~Monshō o Tsugumono-tachi e~ takes place 25 years after the events in Dragon Quest Retsuden: Roto no Monshō. The world is once again in chaos and a young boy, Arosu (アロス), sets out gathering companions to once again save the world from evil.

Soundtrack

Koichi Sugiyama composed and directed the music for the game.[1] The soundtrack included only eight tracks, which have been described as "the foundation for Sugiyama's career", and which have been arranged and incorporated into the soundtracks of later Dragon Warrior.[45] The music has been released in a variety of different formats. The first was as a Drama CD released by Enix on July 19, 1991, incorporating a spoken story with the music.[46] This was followed by Super Famicom Edition Symphonic Suite Dragon Quest I, published by Sony Records on January 12, 1994, which contains orchestral versions of the tracks performed by the London Philharmonic Orchestra as well as the original versions of the tunes.[47]

These orchestral tracks were also included in Symphonic Suite Dragon Quest I•II, released by SME Visual Works on August 23, 2000 and reprinted by King Records on October 7, 2009; this album combined the orchestral albums for Dragon Warrior I and II.[48] The orchestral tracks were again released in the Symphonic Suite Dragon Quest I album, which also included orchestral versions of the sound effects from the game.[45] Music from the game has been performed in numerous live concerts, many of which have been later released as albums such as Dragon Quest in Concert and Suite Dragon Quest I•II.[49][50]

Reception and sales

| Publication | Score | |

|---|---|---|

| GBC | NES | |

| GameSpot | 8.0 / 10 | |

| IGN | 9.6 / 10 | 7.8 / 10 |

| Nintendo Power | 8 / 10 | 3 / 5 |

Dragon Quest was wildly popular in Japan, and became the first in a series that now includes nine games with several spin-offs, including Dragon Quest Monsters. The release of Dragon Quest is regarded as a milestone in the history of the console RPG, a popular genre that also includes the Final Fantasy series. It was one of the first console RPGs to use a top-down perspective, a staple of 2D console RPGs, and has since been cited by GameSpot as one of the fifteen most influential games in the history of video games.[51] IGN called it the 8th best NES game of all time on their "Top 100 NES Games of all Time" and the 92nd best game of all time on their "Top 100 Games" list.[52][53]

The initial NES version of Dragon Warrior was met with an overall average results. Nintendo Power critics ranked the NES release of Dragon Warrior an average of 3/5 upon its original release, later rating it the 140th best game made on a Nintendo System in Nintendo Power's Top 200 Games list in 2006.[11][54] Later reviews of the game after its success were made by IGN who gives it a 7.8 / 10,[55] and TopTenReviews who gives it a 2.3667 out of 4.[56] The GBC remake received fairly high marks for its release. Released along with Dragon Warrior II the dual game cartridge received an 8.0 out of 10 from IGN,[57] a 9.6 out of 10 from GameSpot,[58] and 8 out of 10 from Nintendo Power.[59] It also received the RPGamer's Game Boy Color Award of the Year for 2000.[60]

Seemingly primitive by today's standards, Dragon Warrior features one-on-one combat,[8] a limited array of items and equipment,[3][8] ten spells,[8][61] five towns, and five dungeons.[8] Chi Kong Lui of Gamecritics commented on how the game added "realism" to video games, writing "If a player perished in Dragon Warrior, he or she had to suffer the dire consequences of losing progress and precious gold. That element of death evoked a sense of instinctive fear and tension for survival".[62] This, he said, allowed NES players to identify with the main character on a much larger scale. IGN writer Mark Nix compared the game's seemingly archaic plot to more modern RPGs, stating that "noble blood means nothing when the society is capitalist, aristocratic, or militaristic. Damsels don't need rescuing -- they need a battle axe and some magic tutoring in the field."[37] The staff of Gamespy wrote that for many gamers, Dragon Warrior was their first exposure to the console RPG. "It opened my eyes to a fun new type of gameplay. Suddenly strategy (or at least pressing the "A" button) was more important than reflex, and the story was slightly (slightly!) more complex than the "rescue the princess" stuff I'd seen up 'till then. After all, Dragon Warrior was only half-over when you rescued its princess", they recalled when reviewing Dragon Quest VIII.[63] 1up staff explained that the series was not immensely popular at first simply because "RPGs were not something American console gamers were used to," going on to say that it would take a decade for the genre to be "flashy enough to distract from all of those words they made you read."[64] In a column called "Play Back", Nintendo Power's staff reflected on the game, naming its "historical significance" as its greatest aspect, noting that "playing Dragon Warrior these days can be a bit of a chore."[23]

Dragon Quest Retsuden: Roto no Monshō - To the Children Who Inherit the Emblem has sold well in Japan. For the week of August 26 through September 1, 2008, volume 7 was ranked 9th in Japan having sold 59,540 copies.[65] For the week of February 24 through March 2, 2009, volume 8 was ranked 19th in Japan having sold 76,801 copies.[66] For the week of October 26 through November 1, 2009, volume 9 was ranked 16th in Japan having sold 40,492 copies for a total of 60,467.[43]

Legacy

Bits and pieces of Dragon Warrior had been seen in videogames before, but never all sewn up together so neatly. DW's incredible combination of gameplay elements established it as THE template for console RPGs to follow.

William Cassidy, The GameSpy Hall of Fame: Dragon Warrior[67]

Dragon Warrior has been listed as a genre builder for console role-playing games. While bits and pieces had been in previous games of the genre, Dragon Warrior set the template for all others to follow. Almost all of the elements of the game became the foundation for every game of the genre to come from gameplay to narrative.[2][67][68] While Final Fantasy has been considered more important due to its popularity and attention in North America, the fundamentals on which that game was based were laid down by Dragon Warrior.[51][67]

In Japan, Dragon Quest became a national phenomenon which inspired spinoff media and other fan items, like figurines. It is said that asking the common Japanese individual to draw a slime will result in them drawing a shape similar to that of the game's slime.[67]

Notes

- ^ DragonQuest was published by wargame publisher Simulations Publications in the 1980s until the company's bankruptcy in 1982. It was then and purchase by TSR, Inc., which then published it as an alternate line to Dungeons & Dragons until 1987.

- ^ The NES translation does not use true Elizabethan (Early Modern) English, but instead has Elizabethan elements in its dialogue.

References

- ^ a b c Johnston, Chris; Ricciardi, John; Ohbuchi, Yotaka (2001-12-01). "Role-Playing 101: Dragon Warrior". Electronic Gaming Monthly: 48–51.

- ^ a b "The GameSpy Hall of Fame: Dragon Warrior". Gamespy. p. 1. Retrieved October 9, 2009.

- ^ a b c d Kalata, Kurt. "The History of Dragon Quest". Features. Gamasutra. p. 1. Retrieved 2009-09-29.

- ^ Prima Games, ed. (2000). Dragon Warrior I and II Official Strategy Guide. Prima Publishing. p. 105. ISBN 0-7615-3157-2.

- ^ a b c d Chunsoft (1989). Dragon Warrior (Nintendo Entertainment System). Nintendo.

- ^ Majaski, Craig (October 9, 2000). "Dragon Warrior 1&2 review". Retrieved 2009-09-23.

- ^ a b (1989) Nintendo, Enix Corporation Dragon Warrior Instruction Manual (in English).

- ^ a b c d e f g (1989) Nintendo of America Inc., Tokuma Shoten U.S. Edition, Enix Corporation Licensed exclusively to Nintendo of America Inc., Nintendo Power Strategy Guide Published by Nintendo of America Inc. and Tokuma Shoten Dragon Warrior Strategy Guide (in English).

- ^ Editors of Nintendo Power: Nintendo Power July - August, 1989; issue 7 (in English). Nintendo of America, Tokuma Shoten Publishing, 40.

- ^ Chunsoft (1986). Dragon Quest (Famicom). Enix.

- ^ a b c Editors of Nintendo Power: Nintendo Power May - June, 1989; issue 6 (in English). Nintendo of America, Tokuma Shoten Publishing, 52.

- ^ a b c Dragon Warrior, 1UP

- ^ a b "Dragon Warrior Release Information for NES". GameFAQs. Retrieved 2009-10-09.

- ^ a b c d "Dragon Quest: Sential of the Starry Skies". Iwata Asks. Square-Enix. The History of Dragon Quest. Retrieved 2010-12-05.

- ^ a b c Editors of Nintendo Power: Nintendo Power Volume 238 (in English). Future US Inc., 84.

- ^ Kurt Kalata, The History of Dragon Quest, Gamasutra

- ^ a b Goro Gotemba & Yoshiyuki Iwamoto (2006), Japan on the upswing: why the bubble burst and Japan's economic renewal, p. 201, Algora Publishing, ISBN 0875864627

- ^ Oleg, p. "Brief History of Japanese RPGs"

- ^ Nintendo Power volume 221. Future US. 2007. pp. 78–80.

At the time I first made Dragon Quest, computer and video game RPGs were still very much in the realm of hardcore fans and not very accessible to other players. So I decided to create a system that was easy to understand and emotionally involving, and then placed my story within that framework.

- ^ Vestal 1998a, p. "Dragon Quest"

- ^ 20 Open World Games: Dragon Quest III, a.k.a. Dragon Warrior III, Gamasutra

- ^ "Dragon Quest for Mobile Phones". 2004. Retrieved 2007-10-14.

- ^ a b Editors of Nintendo Power: Nintendo Power February, 2009; issue 2 (in English). Future US Inc, 84. Retrieved February 1, 2010.

- ^ Editors of Nintendo Power: Nintendo Power May - June, 1989; issue 6 (in English). Nintendo of America, Tokuma Shoten Publishing, 52-53.

- ^ Editors of Nintendo Power: Nintendo Power July - August, 1989; issue 7 (in English). Nintendo of America, Tokuma Shoten Publishing, 39-50.

- ^ Editors of Nintendo Power: Nintendo Power September - October, 1989; issue 8 (in English). Nintendo of America, Tokuma Shoten Publishing, 20-27.

- ^ Editors of Nintendo Power: Nintendo Power November - December, 1989; issue 9 (in English). Nintendo of America, Tokuma Shoten Publishing, 5.

- ^ Editors of Nintendo Power: Nintendo Power March - April, 1990; issue 11 (in English). Nintendo of America, Tokuma Shoten Publishing, 4, 51-54.

- ^ Editors of Nintendo Power: Nintendo Power January, 1996; issue 80 (in English). Nintendo of America, Tokuma Shoten Publishing, 58.

- ^ Dustin Hubbard and Dwaine Bullock (unknown). "Dragon Quest I+II at DQ Shrine". Retrieved 2008-04-10.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) - ^ Churnsoft (1993). Dragon Quest I & II (Super Famicom). Enix.

- ^ "ROMHacking.net search". 2007. Retrieved 2008-04-18.

- ^ Dustin Hubbard and Dwaine Bullock. "BS Dragon Quest at DQ Shrine". Retrieved 2008-04-10.

- ^ "BS Dragon Quest". Dragon Quest/Dragon Warrior Shrine. Retrieved 2009-10-09.

- ^ Churnsoft (1998). BS Dragon Quest (Super Famicom). Satellaview.

- ^ Dustin Hubbard and Dwaine Bullock. "Dragon Warrior I+II at DQ Shrine". Retrieved 2008-04-10.

- ^ a b Nix, Mark. "Dragon Warrior I & II Review". IGN. Retrieved 2009-10-06.

- ^ a b TOSE (2000). Dragon Warrior I & II (Game Boy Color). Enix.

- ^ "ドラゴンクエスト列伝 ロトの紋章 完全版" (in Japanese). Square-Enix. Retrieved 2009-11-09.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "ロトの紋章―ドラゴンクエスト列伝 (21) (ガンガンコミックス) (コミック)" (in Japanese). Amazon. Retrieved 2009-11-09.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "Japan's Sony PSP Manga Distribution Service Detailed". News. Anime News Network. 2009-09-24. Retrieved 2009-11-09.

- ^ "ドラゴンクエスト列伝・ロトの紋章 [VHS]" (in Japanese). Amazon. Retrieved 2009-11-09.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Japanese Comic Ranking, October 26-November 1". News. Anime News Network. 2009-11-04. Retrieved 2009-11-09.

- ^ "ドラゴンクエスト列伝 ロトの紋章 ~紋章を継ぐ者達へ~" (in Japanese). Square-Enix. Retrieved 2009-11-09.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Gann, Patrick (2008-05-15). "Symphonic Suite Dragon Quest I". RPGFan. Retrieved 1 December 2009.

- ^ Gann, Patrick (2001-09-13). "CD Theater Dragon Quest I". RPGFan. Retrieved 1 December 2009.

- ^ Gann, Patrick (2008-11-18). "Super Famicom Edition Symphonic Suite Dragon Quest I". RPGFan. Retrieved 1 December 2009.

- ^ Prievert, Alexander (2006-02-07). "Super Famicom Edition Symphonic Suite Dragon Quest I". RPGFan. Retrieved 1 December 2009.

- ^ Patrick Gann (2007). "Dragon Quest in Concert". Retrieved August 31, 2007.

- ^ Gann, Patrick (2009-10-27). "http://rpgfan.com/soundtracks/dq1&2-suite/index.html". RPGFan. Retrieved 1 December 2009.

{{cite web}}: External link in|title= - ^ a b "15 Most Influential Games". 2005. Retrieved 2007-09-01.

- ^ Moriarty, Colin. "Top 100 NES Games of all Time". IGN. Retrieved 2009-10-16.

- ^ "Top 100 Games of all Time". IGN. Retrieved 2009-10-27.

- ^ "NP Top 200". Nintendo Power. Vol. 200. February 2006. pp. 58–66.

- ^ "Dragon Warrior". IGN. Retrieved 2009-12-05.

- ^ "Dragon Warrior". TopTenReviews. Retrieved 2009-12-05.

- ^ Nix, Marc (2000). "Dragon Warrior I & II Return to the days of yore with Enix's Game Boy Color RPG revival". Retrieved 2008-04-10.

- ^ "Dragon Warrior I & II for Game Boy Color Review". 2000. Retrieved 2008-04-10.

- ^ "Dragon Warrior I & II for Game Boy Color Review". review. 2000. Retrieved 2008-04-10.

- ^ "RPGamer's Awards 2000: Game Boy Color RPG of the Year". 2000. Retrieved 2008-04-10.

- ^ Editors of Nintendo Power: Nintendo Power July - August, 1989; issue 7 (in English). Nintendo of America, Tokuma Shoten Publishing, 44.

- ^ Chi Kong Lui. "Dragon Warrior I & II". Gamecritics.com. Retrieved 2009-10-06.

- ^ Gamespy staff. "The Annual E3 Awards 2005". Gamespy.com. Retrieved 2009-10-09.

- ^ Mackey, Bob. "Smart Bombs: Celebrating gaming's most beloved flops". 1UP.com. Retrieved 2009-10-13.

- ^ "Japanese Comic Ranking, August 26–September 1". News. Anime News Network. 2009-09-03. Retrieved 2009-11-09.

- ^ "Japanese Comic Ranking, February 24–March 2". News. Anime News Network. 2009-09-03. Retrieved 2009-11-09.

- ^ a b c d "The GameSpy Hall of Fame: Dragon Warrior". Gamespy. p. 2. Retrieved October 9, 2009.

- ^ Andrew Vestal (1998-11-02). "Other Game Boy RPGs". GameSpot. Retrieved 2009-11-18.

External links