Palestine (region): Difference between revisions

→British Mandate (1920-1948): Fixed text, added reference |

→Ottoman period: Added sources on Arab immigration |

||

| Line 36: | Line 36: | ||

===Ottoman period=== |

===Ottoman period=== |

||

After the [[Ottoman Empire|Ottoman]] conquest, the name disappeared as the ''official'' name of an administrative unit, as the Turks often called their (sub)provinces after the capital. Since its 1516 incorporation in the Ottoman Empire, it was part of the'' [[vilayet]]'' ([[Subdivisions of the Ottoman Empire|province]]) of Damascus-Syria until 1660, next of the ''vilayet'' of [[Sidon|Saida]] (seat in Lebanon), shortly interrupted by the 7 March 1799 - July 1799 French occupation of Jaffa, Haifa, and Caesarea. |

After the [[Ottoman Empire|Ottoman]] conquest, the name disappeared as the ''official'' name of an administrative unit, as the Turks often called their (sub)provinces after the capital. Since its 1516 incorporation in the Ottoman Empire, it was part of the'' [[vilayet]]'' ([[Subdivisions of the Ottoman Empire|province]]) of Damascus-Syria until 1660, next of the ''vilayet'' of [[Sidon|Saida]] (seat in Lebanon), shortly interrupted by the 7 March 1799 - July 1799 French occupation of Jaffa, Haifa, and Caesarea. On 10 May 1832 it was one of the Turkish provinces annexed by [[Muhammad Ali of Egypt|Muhammad Ali]]'s shortly imperialistic, khedival Egypt (remained nominally Ottoman), but in November 1840 direct Ottoman rule was restored. |

||

On 10 May 1832 it was one of the Turkish provinces annexed by [[Muhammad Ali of Egypt|Muhammad Ali]]'s shortly imperialistic, khedival Egypt (remained nominally Ottoman), but in November 1840 direct Ottoman rule was restored. |

|||

Still the old name remained in popular and semi-official use. Many examples of its usage in the 16th and 17th centuries have survived [Gerber]. During the 19th century, the "Ottoman Government employed the term ''Arz-i Filistin'' (the 'Land of Palestine') in official correspondence, meaning for all intents and purposes the area to the west of the River Jordan which became 'Palestine' under the British in 1922" [Mandel, page ''xx'']. Amongst the educated Arab public, ''Filastin'' was a common concept, referring either to the whole of Palestine or to the Jerusalem ''[[sanjaq]]'' alone [Porath]. |

Still the old name remained in popular and semi-official use. Many examples of its usage in the 16th and 17th centuries have survived [Gerber]. During the 19th century, the "Ottoman Government employed the term ''Arz-i Filistin'' (the 'Land of Palestine') in official correspondence, meaning for all intents and purposes the area to the west of the River Jordan which became 'Palestine' under the British in 1922" [Mandel, page ''xx'']. Amongst the educated Arab public, ''Filastin'' was a common concept, referring either to the whole of Palestine or to the Jerusalem ''[[sanjaq]]'' alone [Porath]. |

||

The Ottoman Sultan embraced investments by European (including Zionist) parties. Significant numbers of Jews began making [[Aliyah]] to the Holy Land to build collective farms and eventually established the new city of Tel Aviv. The Sultanate benefited greatly from the broader economic activity that ensued. |

The Ottoman Sultan embraced investments by European (including Zionist) parties. Significant numbers of Jews began making [[Aliyah]] to the Holy Land to build collective farms and eventually established the new city of Tel Aviv. The Sultanate benefited greatly from the broader economic activity that ensued. |

||

This development also spurred a considerable immigration of Arabs from the surrounding lands to Palestine. <ref>Arieh Avneri, The Claim of Dispossession, (Tel Aviv: Hidekel Press, 1984), p. 28; Yehoshua Porath, ''The Emergence of the Palestinian-Arab National Movement'', 1918-1929, London: Frank Cass, 1974), pp. 17-18</ref> <ref>John Hope Simpson, ''Palestine: Report on Immigration, Land Settlement and Development'', (London, 1930), p. 126.</ref> According to the Ottoman census of 1905, of Arabs residents involved in migration within Palestine, roughly half represented immigration from outside the itself, with roughly 43 percent originating in other areas of Asia, 39 percent in Africa, and 20 percent in Turkey. <ref>U.O. Schmelz, "Population Characteristics of Jerusalem and Hebron Regions According to Ottoman Census of 1905," in Gar G. Gilbar, ed., Ottoman Palestine: 1800-1914 (Leiden: Brill, 1990), p. 42.</ref> Demographer U.O. Schmelz, in his analysis of the census records, noted that "The above-average population growth of the Arab villages around the city of Jerusalem, with its Jewish majority, continued until the end of the mandatory period. This must have been due—as elsewhere in Palestine under similar conditions—to in-migrants attracted by economic opportunities, and to the beneficial effects of improved health services in reducing mortality—just as happened in other parts of Palestine around cities with a large Jewish population sector." <ref>U.O. Schmelz, "Population Characteristics of Jerusalem and Hebron Regions According to Ottoman Census of 1905," in Gar G. Gilbar, ed., Ottoman Palestine: 1800-1914 (Leiden: Brill, 1990), pp. 32-3.</ref> |

|||

===The 19th and 20th centuries=== |

===The 19th and 20th centuries=== |

||

Revision as of 02:03, 12 April 2006

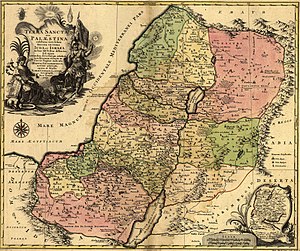

Palestine (Hebrew: פלשתינה Palestina, Arabic: فلسطين Filastīn or Falastīn, see also Canaan, Land of Israel) is one of many historical names for the region between the Mediterranean Sea and the banks of the Jordan River, plus various adjoining lands to the east and south. Many different definitions of the region have been used in the past three millennia (see also definitions of Palestine).

Boundaries and name

Ancient Egyptian writings refer to the region as R-ẖ-n-u (for convenience pronounced Rechenu). Several names for the region are found in the Hebrew Bible: Eretz Yisrael "Land of Israel", Eretz Ha-Ivrim "land of the Hebrews", "land flowing with milk and honey", "land that [God] swore to your fathers to assign to you", "Holy Land", "Promised Land", and "land of the Lord". The portion of the land situated west of the Jordan River was also called "land of Canaan" during the period in which it fell under the control of Egyptian vassals traditionally descended from Canaan the son of Ham. After the split of the United Monarchy into two, the southern part became the Kingdom of Judah and the northern part the Kingdom of Israel.

The term "Palestine" comes from the word Philistine, the name of an ethnic group which lived in the southern coast of the region. The Philistines disappeared as a distinct group by the Assyrian period. The meaning of their ethnonym is uncertain but is sometimes understood in Hebrew to mean "invaders" from the root p-l-sh. What is possibly the earliest mention of them occurs in Egyptian texts which record a people called the P-r/l-s-t (conventionally Peleset), one of the Sea Peoples who invaded Egypt in Ramesses III's reign. The Hebrew name פלשת (Pəléšeth or P(e)léshet, translated Philistia in English) is used in the Bible to denote the coastal region inhabited by the Philistines. The Assyrian emperor Sargon II called the region Palashtu in his Annals. The Greek form Palaistinêi from which English "Palestine" is ultimately derived, was first used in the 5th century BCE by Herodotus who wrote of the "district of Syria, called Palaistinêi". The boundaries of the area he referred to were not explicitly stated, but Josephus used the name only for Philistia. Ptolemy also used the term. In Latin, Pliny wrote of a region of Syria that was "formerly called Palaestina" when describing the eastern coast of the Mediterranean.

History

- Main articles: History of Palestine, History of ancient Israel and Judah, History of Israel.

Roman times

As a result of the First Jewish-Roman War (66–73), Titus sacked Jerusalem and destroyed the Second Temple, leaving only the Western Wall. In 135, following the fall of a Jewish revolt led by Bar Kokhba in 132–135, the Roman emperor Hadrian expelled most Jews from Judea, leaving large Jewish populations in Samaria and the Galilee. He also changed the name of the Roman province of Judea (Israel) to Syria Palaestina named after the Philistines as an insult to the now conquered Jews. In what was considered a form of psychological warfare, the Romans also tried to change the name of Jerusalem to Aelia Capitolina, but that had less staying power. Over time the name Syria Palaestina was shortened to Palaestina, which by then had become an administrative political unit within the Roman Empire.

Byzantine (Eastern Roman Empire) period

In approximately 390, Palaestina was further organised into three units: Palaestina Prima, Secunda, and Tertia (First, Second, and Third Palestine). Palaestina Prima consisted of Judea, Samaria, the coast, and Peraea with the governor residing in Caesarea. Palaestina Secunda consisted of the Galilee, the lower Jezreel Valley, the regions east of Galilee, and the western part of the former Decapolis with the seat of government at Scythopolis. Palaestina Tertia included the Negev, southern Jordan — once part of Arabia — and most of Sinai with Petra the usual residence of the governor. Palestina Tertia was also known as Palaestina Salutaris. This reorganization reduced Arabia to the northern Jordan east of Peraea. Roman administration of Palestine ended temporarily during the Persian occupation of 614–28, then permanently after the Arabs conquered the region beginning in 635.

Caliphate and later Arab rulers

The new Arab rulers divided the province of a-Sham (still Arabic for Syria) into five districts. Jund Filastin (Arabic جند فلسطين, literally "the army or military district of Palestine") was a region extending from the Sinai to south of the plain of Acre. At times it reached down into the Sinai. Major towns included Rafaḥ, Caesarea, Gaza, Jaffa, Nablus, Jericho, Ramla and Jerusalem. Initially Ludd (Lydda) was the capital, but in 717 it was moved to the new city of ar-Ramlah (Ramla). (The capital was not moved to Jerusalem until much later, when the organization into Junds was already breaking down.) Jund al-Urdunn (literally "Jordan") was a region to the north and east of Filastin. Major towns included Tiberias, Legio, Acre, Beisan and Tyre. The capital was at Tiberias. Various political upheavals led to readjustments of the boundaries several times. After the 10th century, the division into Junds began to break down and the Turkish invasions of the 1070s, followed by the first Crusade, completed that process. From the 11th to the 19th centuries we have instances that Filasṭin did not refer to the land of Palestine but to its by then defunct capital ar-Ramla.

- See also the Mideastweb map of "Palestine Under the Caliphs", showing Jund boundaries (external link).

Crusader period

See the articles on the Crusades and the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem.

Mamluk period

After Muslim control over Palestine was reestablished in the 12th and 13th centuries, the division into districts was reinstated, with boundaries that were frequently redrawn. 1263/Jul 1291 the country was part of the Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt.

Around the end of the 13th century, Palestine comprised several of nine ?emirates of Syria, namely the "Kingdoms" of Gaza (including Ascalon and Hebron), Karak (including Jaffa and Legio), Safad (including Safad, Acre, Sidon and Tyre) and parts of the Kingdom of Damascus (sometimes extending as far south as Jerusalem).

By the middle of the 14th century, Syria had again been divided into five districts, of which Filastin included Jerusalem (its capital), Ramla, Ascalon, Hebron and Nablus, while Hauran included Tiberias (its capital).

Ottoman period

After the Ottoman conquest, the name disappeared as the official name of an administrative unit, as the Turks often called their (sub)provinces after the capital. Since its 1516 incorporation in the Ottoman Empire, it was part of the vilayet (province) of Damascus-Syria until 1660, next of the vilayet of Saida (seat in Lebanon), shortly interrupted by the 7 March 1799 - July 1799 French occupation of Jaffa, Haifa, and Caesarea. On 10 May 1832 it was one of the Turkish provinces annexed by Muhammad Ali's shortly imperialistic, khedival Egypt (remained nominally Ottoman), but in November 1840 direct Ottoman rule was restored.

Still the old name remained in popular and semi-official use. Many examples of its usage in the 16th and 17th centuries have survived [Gerber]. During the 19th century, the "Ottoman Government employed the term Arz-i Filistin (the 'Land of Palestine') in official correspondence, meaning for all intents and purposes the area to the west of the River Jordan which became 'Palestine' under the British in 1922" [Mandel, page xx]. Amongst the educated Arab public, Filastin was a common concept, referring either to the whole of Palestine or to the Jerusalem sanjaq alone [Porath].

The Ottoman Sultan embraced investments by European (including Zionist) parties. Significant numbers of Jews began making Aliyah to the Holy Land to build collective farms and eventually established the new city of Tel Aviv. The Sultanate benefited greatly from the broader economic activity that ensued.

This development also spurred a considerable immigration of Arabs from the surrounding lands to Palestine. [1] [2] According to the Ottoman census of 1905, of Arabs residents involved in migration within Palestine, roughly half represented immigration from outside the itself, with roughly 43 percent originating in other areas of Asia, 39 percent in Africa, and 20 percent in Turkey. [3] Demographer U.O. Schmelz, in his analysis of the census records, noted that "The above-average population growth of the Arab villages around the city of Jerusalem, with its Jewish majority, continued until the end of the mandatory period. This must have been due—as elsewhere in Palestine under similar conditions—to in-migrants attracted by economic opportunities, and to the beneficial effects of improved health services in reducing mortality—just as happened in other parts of Palestine around cities with a large Jewish population sector." [4]

The 19th and 20th centuries

In European usage up to World War I, "Palestine" was used informally for a region that extended in the north-south direction typically from Raphia (south-east of Gaza) to the Litani River (now in Lebanon). The western boundary was the sea, and the eastern boundary was the poorly-defined place where the Syrian desert began. In various European sources, the eastern boundary was placed anywhere from the Jordan River to slightly east of Amman. The Negev Desert was not included. [Biger]

Under the Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916, it was envisioned that most of Palestine, when freed by Ottoman control, would become an international zone not under direct French or British colonial control. [1] Shortly thereafter, British foreign minister Arthur Balfour issued the Balfour Declaration of 1917, which laid plans for a Jewish homeland to eventually be established in Palestine.

British Mandate (1920-1948)

Formal use of the English word "Palestine" returned with the British Mandate. During this period, the name "Eretz Yisrael" (Hebrew: ארץ ישראל) was also part of the official name of the territory.

In 1920, the Mandate of Palestine was assigned to Britain by the San Remo Conference, which defined the area as bordered by the Mediterranean Sea, Lebanon, Syria, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and a short stretch of Red Sea coastline between the latter two. These borders include all of present-day Israel, the West Bank, the Gaza Strip, and Jordan. ([2][3] [4]).

Also in 1920, the French drove Faisal bin Husayn from Damascus ending his already negligible control over the region of Transjordan, where local chiefs traditionally resisted any central authority. The sheikhs, who had earlier pledged their loyalty to the Sharif, asked the British to undertake the region's administration. Herbert Samuel asked for the extension of the Palestine government's authority to Transjordan, but at meetings in Cairo and Jerusalem between Winston Churchill and Emir Abdullah in March 1921 it was agreed that Abdullah would administer the territory (initally for six months only) on behalf of the Palestine administration. In the summer of 1921 Transjordan was included within the Mandate, but excluded from the provisions for a Jewish National Home (Gelber, 1997, pp. 6-15). On 24 July, 1922 the League of Nations approved the terms of the British Mandate over Palestine and Transjordan. On 16 September the League formally approved a memorandum from Lord Balfour confirming the exemption of Transjordan from the clauses of the mandate concerning the creation of a Jewish national home and from the mandate's responsibility to facilitate Jewish immigration and land settlement (Sicker, 1999, p. 164). In reality, the British prevented Jews from settling in Transjordan, while Arabs could freely settle in Palestine. ([5] see "Entry of Jews into Transjordan").

Even before the Mandate came into legal effect in 1922 (text), British terminology frequently used '"Palestine" for the part west of the Jordan River and "Trans-Jordan" (or Transjordania) for the part east of the Jordan River [5] [6] [7] [8] [9]. From about 1924 onwards, this terminology was applied consistently during the Mandate period [10], and it is difficult to find any official documents that use any name other than "Palestine and Trans-Jordan" when referring to the whole area of the Mandate. Nevertheless, the fact that "Palestine" was once considered to include lands on the east side of the Jordan River continues even today to have significance in political discourse. (see History of Palestine, History of Jordan).

UN Partition

On 29 November 1947, the United Nations General Assembly passed the United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine (United Nations General Assembly Resolution 181), a plan to resolve the Arab-Jewish conflict by partitioning the territory into separate Jewish and Arab states, with the Greater Jerusalem area (encompassing Bethlehem) coming under international control [11]. Jewish leaders (including the Jewish Agency), accepted the plan, while Palestinian Arab leaders rejected it. Neighboring Arab states also rejected the partition plan. As armed skirmishes between Arab and Jewish paramilitary forces in Palestine continued, the British mandate ended on May 15, 1948, the establishment of the State of Israel having been proclaimed the day before (see Declaration of the Establishment of the State of Israel). The neighboring Arab states immediately attacked Israel following its declaration of independence, and the 1948 Arab-Israeli War ensued. Consequently, the partition plan was never implemented.

Current Status

Following the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, the 1949 Armistice Agreements between Israel and neighboring Arab states eliminated Palestine as a distinct territory. It was divided between Israel, Egypt, Syria and Jordan. [12] [13]

In addition to the UN-partitioned area, Israel captured 26% of the Mandate territory west of the Jordan river. Jordan captured and annexed about 21% of the Mandate territory. Jerusalem was divided, with Jordan taking the eastern parts, including the old city, and Israel taking the western parts. The Gaza Strip was captured by Egypt.

For a description of the massive population movements, Arab and Jewish, at the time of the 1948 war and over the following decades, see Palestinian exodus and Jewish exodus from Arab lands.

From the 1960s onward, the term "Palestine" was regularly used in political contexts. Various declarations, such as the 1988 proclamation of a State of Palestine by the PLO referred to a country called Palestine, defining its borders with differing degrees of clarity, including the annexation of the whole of the State of Israel. Most recently, the Palestine draft constitution refers to borders based on the West Bank and Gaza Strip prior to the 1967 Six-Day War. This so-called Green Line follows the 1949 armistice line; the permanent borders are yet to be negotiated. Furthermore, since 1994, there has been a Palestinian Authority controlling varying portions of historic Palestine.

Demographics

In 1900, Palestine (according to Ottoman statistics) had a population of about 600,000 of which 94% were Arabs (McCarthy). By 1948, the population had risen to 1,900,000, of whom 68% were Arabs, and 32% were Jews (UNSCOP report, including bedouin).

Sources vary as to the cause of this demographic shift.

Sources and references

- ^ Arieh Avneri, The Claim of Dispossession, (Tel Aviv: Hidekel Press, 1984), p. 28; Yehoshua Porath, The Emergence of the Palestinian-Arab National Movement, 1918-1929, London: Frank Cass, 1974), pp. 17-18

- ^ John Hope Simpson, Palestine: Report on Immigration, Land Settlement and Development, (London, 1930), p. 126.

- ^ U.O. Schmelz, "Population Characteristics of Jerusalem and Hebron Regions According to Ottoman Census of 1905," in Gar G. Gilbar, ed., Ottoman Palestine: 1800-1914 (Leiden: Brill, 1990), p. 42.

- ^ U.O. Schmelz, "Population Characteristics of Jerusalem and Hebron Regions According to Ottoman Census of 1905," in Gar G. Gilbar, ed., Ottoman Palestine: 1800-1914 (Leiden: Brill, 1990), pp. 32-3.

- ^ Doreen Ingrams, Palestine Papers 1917-1922 (Murray, 1972)

- Gelber, Yoav (1997). Jewish-Transjordanian Relations 1921-48: Alliance of Bars Sinister. London: Routledge. ISBN 071464675X

- Baruch Kimmerling and Y.S. Migdal, Palestinians: The Making of a People, Harvard University Press 1994 (New print, Forthcomming)

- Mariam Shahin, Palestine - a Guide, Interlink Books 2005

- Sicker, Martin (1999). Reshaping Palestine: From Muhammad Ali to the British Mandate, 1831-1922. Praeger/Greenwood. ISBN 0275966399

- Fabio Maniscalco. Protection, conservation and valorisation of Palestinian Cultural Patrimony Massa Publisher, 2005

- Gideon Biger, Where was Palestine? Pre-World War I perception, AREA (Journal of the Institute of British Geographers) Vol 13, No. 2 (1981) 153-160.

- Guy Le Strange, Palestine under the Moslems (1890; reprinted by Khayats, 1965)

- N. J. Mandel, The Arabs and Zionism before World War I (University of Califormia Press, 1976)

- H. Gerber, "Palestine" and other territorial concepts in the 17th century, International Journal of Middle East Studies, vol 30 (1998) pp 563-572

- Y. Porath, The emergence of the Palestinian-Arab national movement, 1918-1929 (Cass, 1974)

- B. Doumani, Rediscovering Palestine: Merchants and Peasants in Jabal Nablus 1700-1900 (UC Press, 1995)

- Westermann, Großer Atlas zur Weltgeschichte

- J. McCarthy, The Population of Palestine.

- UNSCOP report [14]

- WorldStatesmen- mainly under Isreal

See also

- Land of Israel covers roughly the same region, with a different focus

- State of Palestine

- State of Israel

- Israeli-Palestinian conflict

- Arab-Israeli conflict

- Greater Israel

- Greater Syria

- Palesrael