Grimms' Fairy Tales: Difference between revisions

reverting vandalism |

|||

| (3 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 22: | Line 22: | ||

The first volume of the first edition was published, containing 86 stories; the second volume of 70 stories followed in 1814. For the second edition, two volumes were issued in 1819 and a third in 1822, totalling 170 tales. The third edition appeared in 1837; fourth edition, 1840; fifth edition, 1843; sixth edition, 1850; seventh edition, 1857. Stories were added, and also subtracted, from one edition to the next, until the seventh held 211 tales. All editions were extensively illustrated, first by [[Philipp Grot Johann]] and, after his death in 1892, by Robert Leinweber. |

The first volume of the first edition was published, containing 86 stories; the second volume of 70 stories followed in 1814. For the second edition, two volumes were issued in 1819 and a third in 1822, totalling 170 tales. The third edition appeared in 1837; fourth edition, 1840; fifth edition, 1843; sixth edition, 1850; seventh edition, 1857. Stories were added, and also subtracted, from one edition to the next, until the seventh held 211 tales. All editions were extensively illustrated, first by [[Philipp Grot Johann]] and, after his death in 1892, by Robert Leinweber. |

||

The first volumes were much criticized because, although they were called "Children's Tales", they were not regarded as suitable for children, both for the scholarly information included and the subject matter.<ref>[[Maria Tatar]], ''The Hard Facts of the Grimms' Fairy Tales'', p15-17, ISBN 0-691-06722-8</ref> Many changes through the editions – such as turning the wicked mother of the first edition in ''[[Snow White]]'' and ''[[Hansel and Gretel]]'' (shown in original Grimm stories as Hansel and Grethel) to a stepmother, were |

The first volumes were much criticized because, although they were called "Children's Tales", they were not regarded as suitable for children, both for the scholarly information included and the subject matter.<ref>[[Maria Tatar]], ''The Hard Facts of the Grimms' Fairy Tales'', p15-17, ISBN 0-691-06722-8</ref> Many changes through the editions – such as turning the wicked mother of the first edition in ''[[Snow White]]'' and ''[[Hansel and Gretel]]'' (shown in original Grimm stories as Hansel and Grethel) to a stepmother, were made with an eye to such suitability. They removed sexual references—such as [[Rapunzel]]'s innocently asking why her dress was getting tight around her belly, and thus naïvely revealing her pregnancy and the prince's visits to her stepmother—but, in many respects, violence, particularly when punishing villains, was increased.<ref>A. S. Byatt, "Introduction" p. xlii-iv, Maria Tatar, ed. ''The Annotated Brothers Grimm'', ISBN 0-393-05848-4</ref> |

||

In 1825 the Brothers published their ''Kleine Ausgabe'' or "small edition", a selection of 50 tales designed for child readers. This children's version went through ten editions between 1825 and 1858. |

In 1825 the Brothers published their ''Kleine Ausgabe'' or "small edition", a selection of 50 tales designed for child readers. This children's version went through ten editions between 1825 and 1858. |

||

==== Background ==== |

|||

The 19th century rise of [[romanticism]], [[Romantic nationalism]] and trends in valuing popular culture revived interest in fairy tales, which had otherwise been in decline since their late-17th century peak.<ref name="Jean"/> In Germany a popular collection of tales by [[Johann Karl August Musäus]] had been published between 1782 and 1787;<ref name="Haase2008">{{Harvnb|Haase|2008|p=138}}</ref> the Grimms aided the revival with their folklore collection, built on the conviction that a national identity could be found in popular culture and with the common folk (''volk''). They published tales they decided were a reflection of German cultural identity, but in the first collection they also included the tales of [[Charles Perrault]], published in Paris in 1697, that were written for the [[Salon (gathering)|literary salons]] of an aristocratic audience. Scholar Lydia Jean explains that to reconcile Perrault's aristocratic audience with the idea that the tales originated with the common people, a myth was created that Perrault's work, much of which was original, was an "exact reflection of folklore".<ref name="Jean"/> |

|||

[[File:Arthur Rackham Little Red Riding Hood+.jpg|thumb|left|The Grimms defined "[[Little Red Riding Hood]]", shown here in an illustration by [[Arthur Rackham]], as representative of a uniquely German tale although it existed in various versions and regions.<ref name = "Txxxviff"/>]] |

|||

Directly influenced by Brentano and von Arnim who edited and adapted the folksongs of ''[[Des Knaben Wunderhorn]]'' (''The Boy's Magic Horn'' or [[cornucopia]]),<ref name="Haase2008" /> the brothers began the collection with the purpose of creating a scholarly treatise of traditional stories and of preserving the stories as they had been handed from generation to generation—a practice that was threatened by increased industrialization.<ref name = "Txxxff"/> Maria Tatar, professor of German studies at [[Harvard University]], explains that it is precisely in the handing from generation to generation, and the genesis in the [[oral tradition]], that gives folk tales an important mutability. Versions of tales differ from region to region, "picking up bits and pieces of local culture and lore, drawing a turn of phrase from a song or another story, and fleshing out characters with features taken from the audience witnessing their performance."<ref>{{Harvnb|Tatar|2004|pp=xxxvi}}</ref> |

|||

However, as Tatar explains, the Grimms appropriated as uniquely German stories such as "[[Little Red Riding Hood]]", which had existed in many versions and regions throughout Europe, because they believed that such stories were reflections of Germanic culture.<ref name = "Txxxviff">{{Harvnb|Tatar|2004|pp=xxxviii}}</ref> Furthermore, the brothers saw fragments of old religions and faiths reflected in the stories which they thought continued to exist and survive through the telling of stories.<ref name = "Murphy3ff">{{harvnb|Murphy|2000|pp=3–4}}</ref> |

|||

==== Methodology ==== |

|||

When Jacob returned to Marburg from Paris in 1806, their friend Brentano sought the brothers' help in adding to his collection of folk tales, at which time the brothers began to gather tales in an organized fashion.<ref name = "Z(1988)2ff"/> By 1810 they had produced a manuscript collection of several dozen tales, written after inviting storytellers to their home and transcribing what they heard. These tales were heavily modified in transcription and many had roots in previously written sources.<ref name="H579">{{Harvnb|Haase|2008|p=579}}</ref> At Brentano's request, they printed and sent him copies of the 53 tales they collected for inclusion in his third volume of ''Des Knaben Wunderhorn''.<ref name = "Pitt"/> Brentano either ignored or forgot about the tales, leaving the copies in a church in [[Alsace]] where they were found in 1920. Known as the Ölenberg manuscript, it is the earliest extant version of the Grimms' collection, and has become a valuable source to scholars studying the evolution of the Grimms' collection from the time of its inception. The manuscript was published in 1927 and again in 1975.<ref>{{Harvnb|Zipes|2000|p=62}}</ref> |

|||

Although the brothers gained a reputation for collecting tales from peasants, many tales came from middle-class or aristocratic acquaintances. Wilhelm's wife Dortchen Wild and her family, with their nursery maid, told the brothers some of the more well-known tales, such as “[[Hansel and Gretel]]” and “[[Sleeping Beauty]]”.<ref name="J177ff"/> Wilhelm collected a number of tales after befriending [[August von Haxthausen]], whom he visited in 1811 in [[Westphalia]] where he heard stories from von Haxthausen's circle of friends.<ref name="Z(1988)11ff">{{Harvnb|Zipes|1988|pp=11–14}}</ref> Several of the storytellers were of [[Huguenot]] ancestry, telling tales of French origin such as those told to the Grimms by Marie Hassenpflug, an educated woman of French Huguenot ancestry,<ref name="H579"/> and it is probable that these informants were familiar with Perrault’s ''[[Histoires ou contes du temps passé]]'' (''Stories from Past Times'').<ref name="Jean">{{Harvnb|Jean|2007|pp= 280–282}}</ref> Other tales were collected from the wife of a middle-class tailor, Dorothea Viehmann, also of French descent. Despite her middle-class background, in the first English translation she was characterized as a peasant and given the name ''Gammer Gretel''.<ref name = "Txxxff"/> |

|||

[[File:Walter Crane12.jpg|thumb|Stories such as "[[Sleeping Beauty]]", shown here in a [[Walter Crane]] illustration, had been previously published and were rewritten by the Brothers Grimm.<ref name="Jean"/>]] |

|||

According to scholars such as Ruth Bottigheimer and Maria Tatar some of the tales probably originated in written form during the [[Middle ages|medieval period]] with writers such as [[Giovanni Francesco Straparola|Straparola]] and [[Boccaccio]], but were modified in the 17th century, and again rewritten by the Grimms. Moreover, Tatar writes that the brothers' goal of preserving and shaping the tales as something uniquely German at a time of [[Convention of Artlenburg|French occupation]] was a form of "intellectual resistance", and in so doing they established a methodology for collecting and preserving folklore that set the model to be followed later by writers throughout Europe during periods of occupation.<ref name = "Txxxff">{{Harvnb|Tatar|2004|pp=xxxiv–xxxviii}}</ref> |

|||

==== Writing ==== |

|||

From 1807 onward the brothers added to the collection. Jacob established the framework that was maintained through many iterations. By 1815 until his death, Wilhelm assumed sole responsibility for editing and rewriting the tales. Zipes explains that the process of editing included re-composing the tales in a stylistically similar manner, adding dialogue, removing pieces "that might detract from a rustic tone", improving the plots and incorporating psychological motifs.<ref name="Z(1988)11ff"/> Ronald Murphy writes in ''The Owl, the Raven, and the Dove'' that the brothers, and in particular Wilhelm, additionally added religious and spiritual motifs to the tales. He believes that Wilhelm "gleaned" bits of [[neopaganism|old Germanic faiths]], [[Norse mythology]], Roman and Greek mythology and from biblical stories that he reshaped.<ref name = "Murphy3ff"/> |

|||

Over the years, Wilhelm worked extensively on the prose, expanded and added detail to the stories to the point that many grew to be twice the length as in the earliest published editions.<ref name = "T(2004)xiff">{{Harvnb|Tatar|2004|pp=xi–xiii}}</ref> In the later editions Wilhelm polished the language to make it more enticing to a bourgeois audience, eliminated sexual elements, and added Christian elements. After 1819 he began writing for children (children were not initially considered the primary audience), adding entirely new tales or adding new elements that were often strongly didactic to existing tales.<ref name="Z(1988)11ff"/> |

|||

Some changes were made in light of unfavorable reviews, particularly from those who objected that not all the tales were suitable for children because of scenes of violence and sexuality.<ref name = "T(1987)15ff">{{Harvnb|Tatar|1987|pp=15–17}}</ref> He worked to modify plots for of the many stories: for example, "[[Rapunzel]]" in the first edition of ''Kinder- und Hausmärchen'' clearly shows the relationship between the prince and the girl in the tower as sexual, which he edited out in subsequent editions.<ref name = "T(2004)xiff"/> Tatar writes that morals were added (in the second edition a king's regret was added to the scene in which his wife is burned at the stake), and often the characters in the tale were amended to appear more German: "every [[fairy]] (''Fee''), prince (''Prinz'') and princess (''Prinzessin'') (all words of French origin) was transformed into a more Teutonic-sounding enchantress (''Zauberin'') or wise woman (''weise Frau''), king's son (''Königssohn''), king's daughter (''Königstochter'')."<ref>{{Harvnb|Tatar|1987|p=31}}</ref> |

|||

==== Themes and analysis ==== |

|||

The Grimms' legacy contains legends, [[novellas]] and folk stories, the vast majority of which were not intended as children's tales. Deeply concerned by the content of some of the tales—such as those that showed children being eaten—von Armin suggested they be removed. Instead the brothers added an introduction with cautionary advice that parents steer children toward age-appropriate stories. Despite von Armin's unease, none of the tales were eliminated from the collection, in the brothers' belief that all the tales were of value and reflected inherent cultural qualities. Furthermore, the stories were didactic in nature at a time when discipline relied on fear, according to scholar [[Linda Dégh]], who explains that tales such as "[[Little Red Riding Hood]]" and "[[Hansel and Gretel]]" were written to be "warning tales" for children.<ref name = "D91ff">{{Harvnb|Dégh|1979|pp=91–93}}</ref> |

|||

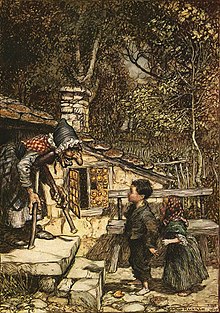

[[File:Hansel-and-gretel-rackham.jpg|thumb|left|''[[Hansel and Gretel]]'', illustrated by [[Arthur Rackham]], was a "warning tale" for children.<ref name = "D91ff"/>]] |

|||

The stories in ''Kinder- und Hausmärchen'' include scenes of violence that have since been sanitized. For example the Grimms' version of "[[Snow White]]" ends with the stepmother dancing at Snow White's wedding wearing a pair of red-hot iron shoes that kill her; another story has a servant being pushed into a barrel "studded with sharp nails" and then rolled down the street.<ref name = "NG"/> The Grimms' version of "[[The Frog Prince (story)|The Frog Prince]]" describes the princess throwing the frog against a wall instead of kissing him. To some extent the cruelty and violence may have been a reflection of medieval culture from which the tales originated, such as scenes of witches burning, as described "[[The Six Swans]]".<ref name = "NG"/> |

|||

Tales with a spinning [[Motif (folkloristics)|motif]] are broadly represented in the collection. In her essay "Tale Spinners: Submerged Voices in Grimms' Fairy Tales", children's literature scholar Bottigheimer explains that these stories reflect the degree to which spinning was crucial in the life of women in the 19th century and earlier. Spinning, and particularly the spinning of [[flax]], was commonly performed in the home by women. Although many stories begin by describing the occupation of a main character, as in "There once was a miller", as an occupation spinning is never mentioned, probably because the brothers did not consider it an occupation. Instead, spinning was a communal activity, frequently performed in a ''Spinnstube'' (spinning room), a place where women most likely kept the oral traditions alive by telling stories while engaged in tedious work.<ref name="B142ff">{{Harvnb|Bottigheimer|1982|pp=142–146}}</ref> In the stories, a woman's personality is often reflected by her attitude toward spinning: a wise woman might be a spinster, and Bottigheimer explains the [[Spindle (textiles)|spindle]] was the symbol of a "diligent, well-ordered womanhood."<ref>{{Harvnb|Bottigheimer|1982|p=143}}</ref> In some stories, such as "[[Rumpelstiltskin]]", spinning is associated with a threat; in others spinning might be avoided by a character who is either too lazy or not accustomed to spinning because of her high social status.<ref name="B142ff"/><!-- this needs more work; or develop in the KHM article --> |

|||

The tales were also criticized for being insufficiently German, which not only influenced the tales the brothers included, but their use of language; whereas scholars such as Heinz Rölleke say the stories are an accurate depiction of German culture, showing "rustic simplicity [and] sexual modesty".<ref name = "NG"/> German culture is deeply rooted in the forest (''wald''), a dark dangerous place to be avoided, most particularly the old forests with large oak trees, and yet a place to which Little Red Riding Hood's mother sent her daughter to deliver food to grandmother's house.<ref name = "NG"/><!-- either something got lost here or it needs expansion --> |

|||

[[File:Rumpelstiltskin-Crane1886.jpg|thumb|300px|"[[Rumpelstiltskin]]", shown here in an illustrated border by [[Walter Crane]], is an example of a "spinning tale".]] |

|||

Some critics such as Alistair Hauke, use [[Jungian]] analysis to say that the deaths of the brothers' father and grandfather are the reason for the Grimms' tendency to idealize and excuse fathers, as well as the predominance of female villains in the tales such as the [[wicked stepmother]]s, such as the evil stepmother and stepsisters in "Cinderella", but this disregards the fact that they were collectors, not authors of the tales.<ref>{{Harvnb|Alister|Hauke|1998|pp=216–219}}</ref> Another possible influence can be found in the selection of stories such as "[[The Twelve Brothers]]", which mirrors the brothers' family structure of one girl and several brothers overcoming opposition.<ref>{{Harvnb|Tatar|2004|p=37}}</ref> Zipes believes that a number of the stories show autobiographical elements and that the brothers may have used their work as a "quest" to replace the family life they lost when their father died. The collection includes 41 tales about siblings, which Zipes believes are representative of Jacob and Wilhelm. Many of the sibling stories follow a simple plot in which the characters lose a home, work industriously at a specific task, and in the end find a new home.<ref>{{Harvnb|Zipes|1988|pp=39–42}}</ref> |

|||

==== Editions ==== |

|||

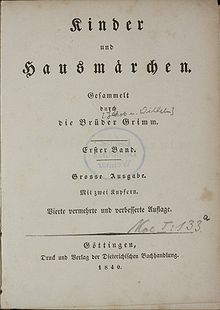

Between 1812 and 1864 ''Kinder- und Hausmärchen'' was published 17 times: seven of the "Large edition" (''Große Ausgabe'') and ten of the "Small edition" (''Kleine Ausgabe''). The Large editions contained all the tales collected to date, extensive annotations and scholarly notes written by the brothers; the Small editions had only 50 tales and were intended for children. [[Ludwig Emil Grimm|Emil Grimm]], Jacob and Wilhelm's younger brother, illustrated the Small editions adding Christian symbolism to the drawings, such as depicting Cinderella's mother as an angel and adding a bible to the bedside table of Little Red Riding Hood's grandmother.<ref name = "Z218ff"/> |

|||

[[File:Kinder title page.jpg|thumb|300px|Frontispiece and title-page, illustrated by [[Ludwig Emil Grimm]] of the 1819 edition of ''[[Grimms' Fairy Tales|Kinder- und Hausmärchen]]'']] |

|||

The first volume was published in 1812 with 86 folktales,<ref name="J177ff">{{Harvnb|Joosen|2006|pp=177–179}}</ref> and a second volume with 70 additional tales was published late in 1814 (dated 1815 on the title page); together the two volumes and their 156 tales are considered the first of the Large (annotated) editions.<ref name="Michaelis-Jena"/><ref name = "Z(2000)276ff">{{Harvnb|Zipes|2000|pp = 276–278}}</ref> A second expanded edition with 170 tales was published in 1819, followed in 1822 by a volume of scholarly commentary and annotations.<ref name = "Pitt"/><ref name = "T(1987)15ff"/> Five more Large editions were published in 1837, 1840, 1843, 1850 and 1857. The seventh and final edition of 1857 contained 211 tales—200 numbered folk tales and the rest were legends.<ref name = "Pitt"/><ref name = "T(1987)15ff"/><ref name = "Z(2000)276ff"/> |

|||

In Germany ''Kinder- und Hausmärchen'' was also released in a "popular poster-sized ''Bilderbogen'' (broadsides)"<ref name = "Z(2000)276ff"/> format and in single story formats for the more popular tales such as "Hansel and Gretel". Pirated editions became common; the stories were often added to collections by other authors as the tales became a focus of interest for children's book illustrators,<ref name = "Z(2000)276ff"/> with well-known artists such as [[Arthur Rackham]], [[Walter Crane]] and [[Edmund Dulac]] illustrating the tales; a popular edition that sold well, released in the mid-19th century, included elaborate [[etching]]s by [[George Cruikshank]].<ref>{{Harvnb|Haase|2008|p=73}}</ref><!-- redo again here --> At the deaths of the brothers, the copyright went to Hermann Grimm (Wilhelm's son) who continued the practice of printing the volumes in expensive and complete editions, however after 1893 when copyright lapsed the stories began to be published in many formats and editions.<ref name = "Z(2000)276ff"/> In the 21st century, ''Kinder- und Hausmärchen'', commonly called ''Grimms' Fairy Tales'' in English, is a universally recognized text. Jacob and Wilhelm's collection of stories has been translated to over 160 languages with 120 different editions of the text are available for sale in the US alone.<ref name = "NG">{{cite web|last=O'Neill|first=Thomas|title=Guardians of the Fairy Tale: The Brothers Grimm|url=http://www.nationalgeographic.com/grimm/article.html|work=National Geographic|publisher=National Geographic Society|accessdate=March 18, 2012}}</ref> |

|||

=== Philology === |

|||

[[File:Pied Piper2.jpg|thumb|left|''Deutsche Sagen'', (''German Legends'') included stories such as "[[The Pied Piper of Hamelin]]", shown here in an illustration by [[Kate Greenaway]].]] |

|||

During their studies at the University of Marburg the brothers came to see culture as tied to language, and regarded the purest cultural expression in the [[grammar]] of a language. For this reason they began to distance themselves from the practices of Brentano and the other romanticists who frequently changed the original oral style of folk tales to fit a literary style that the brothers considered artificial; they believed that the style of the people (the ''volk'') represented a natural and divinely inspired poetry (''naturpoesie'') as opposed to the ''kunstpoesie'' (art poetry) which they thought of as artificially constructed.<ref name = "Z(1988)32ff"/><ref name = "D84ff">{{Harvnb|Dégh|1979|pp=84–85}}</ref> As literary historians and scholars they delved into the origins of stories and attempted to retrieve them from the oral tradition without loss of the original traits of oral language.<ref name = "Z(1988)32ff">{{Harvnb|Zipes|1988|pp=32–35}}</ref> |

|||

The brothers strongly believed the dream of national unity and independence relied on a full knowledge of the cultural past that was reflected in folklore.<ref name = "D84ff"/> They worked to discover and crystallize a kind of Germanness in the stories they collected because they believed that folklore contained kernels of ancient mythologies and beliefs, crucial to understanding the essence of German culture,<ref name = "Txxxff"/> and by examining culture from a philological point-of-view they sought to establish connections between German law, culture, and local beliefs.<ref name = "Z(1988)32ff"/> |

|||

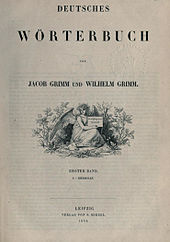

[[File:German dictionary.jpg|thumb|upright|Frontispiece of 1854 edition of ''German Dictionary'' (''Deutsches Wörterbuch'')]] |

|||

The Grimms considered the tales to have origins in traditional Germanic folklore, which they thought had been "contaminated" by later literary tradition.<ref name = "Txxxff"/> In the shift from the oral tradition to the printed book, tales were translated from regional dialects to [[Standard German]] (''Hochdeutsch'' or High German),<ref>{{Harvnb|Zipes|1994|p=14}}</ref> however, over the course of the many modifications and revisions, the Grimms sought to reintroduce regionalisms, dialects and low German to the tales—to re-introduce the language of the original form of the oral tale.<ref>{{Harvnb|Robinson|2004|pp=47–49}}</ref> |

|||

As early as 1812, they published a version of the ''[[Lay of Hildebrand]]'', a 9th-century German heroic song, along with ''Die beiden ältesten deutschen Gedichte aus dem achten Jahrhundert: Das Lied von Hildebrand und Hadubrand und das Weißenbrunner Gebet'', (''The Two Oldest German Poems of the Eighth Century: The Song of Hildebrand and Hadubrand and the Wessobrunn Prayer''), the earliest known German heroic song.<ref name = "Hetting"/> |

|||

Between 1816 and 1818 the brothers published a two-volume work titled ''[[Deutsche Sagen]]'', (''German Legends'') consisting of 585 German legends.<ref name="Michaelis-Jena">{{Harvnb|Michaelis-Jena|1970|p=84}}</ref> Jacob undertook most of the work of collecting and editing the legends that he organized according to region and historical (ancient) legends,<ref name="H429ff"/> and which were about real people or events.<ref name = "Hetting"/> Meant to be a scholarly work, the historical legends were often taken from secondary sources, interpreted, modified and rewritten, resulting works "that were regarded as trademarks".<ref name="H429ff"/> Although some scholars criticized the Grimm's methodology in collecting and rewriting the legends, conceptually they set an example for legend collections that was to be followed by others throughout Europe. Unlike the collection of folk tales, ''Deutsche Sagen'' sold poorly.<ref name="H429ff">{{Harvnb|Haase|2008|pp=429–431}}</ref> |

|||

Less well-known, is the brothers' monumental scholarly work on a German dictionary, the ''Deutsches Wörterbuch'', which they began in 1838. Not until 1852 did they begin publishing the dictionary in installments.<ref name="H429ff"/> The work on the dictionary could not be finished in their lifetime because in it they gave a history and analysis of each word.<ref name = "Hetting"/> |

|||

{{clear}} |

|||

== Reception and legacy == |

|||

[[File:Gedenktafel Alte Potsdamer Str 5 (Tierg) Brüder Grimm.jpg|thumb|Berlin memorial plaque, Brüder Grimm, Alte Potsdamer Straße 5, Berlin-Tiergarten, Germany]] |

|||

[[File:1000 DM Serie4 Vorderseite.jpg|thumb|Design of the front of the 1992 1000 [[Deutsche Mark]] showing the Brothers Grimm<ref>Deutsche Bundesbank (Hrsg.): Von der Baumwolle zum Geldschein. Eine neue Banknotenserie entsteht. 2. Auflage. Verlag Fritz Knapp GmbH, Frankfurt am Main 1996, ISBN 3-611-00222-4, S. 103.</ref>]] |

|||

''Kinder- und Hausmärchen'' was not an immediate bestseller, but its popularity grew with each edition.<ref name="Z(1988)15ff"/> The early editions attracted lukewarm critical reviews, generally on the basis that the stories were unappealing to children. The brothers responded with modifications and rewrites in order to increase the book's market appeal to that demographic.<ref name = "Txxxff"/> By the 1870s the tales had increased greatly in popularity, to the point they were added to the teaching curriculum in [[Prussia]]. In the 20th century the work has maintained status as second only to the bible as the most popular book in Germany. Its sales generated a mini-industry of criticism which analyzed the tales folkloric content in the context of literary history, socialism and psychological elements often along [[Freudian]] and [[Jungian]] lines.<ref name="Z(1988)15ff">{{Harvnb|Zipes|1988|pp=15–17}}</ref> |

|||

In their research, the brothers made a science of the study of folklore (see [[folkloristics]]), generating a model of research that "launched general fieldwork in most European countries",<ref name = "D87ff">{{Harvnb|Dégh|1979|p=87}}</ref> and setting standards for research and analysis of stories and legends that made them pioneers in the field of folklore in the 19th century.<ref>{{Harvnb|Zipes|1981|163}}</ref> |

|||

During the [[Third Reich]] the Grimms' stories were used to foster nationalism and the [[Nazi party]] decreed ''Kinder- und Hausmärchen'' was a book each household should own; later in [[occupied Germany]] the book was banned for a period.<ref name = "D95ff">{{Harvnb|Dégh|1979|pp=94–96}}</ref> In the US, the 1937 release of [[Walt Disney]]'s ''[[Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937 film)|Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs]]'' shows the triumph of good over evil, innocence over oppression, according to Zipes: a popular theme that Disney repeated in 1959 during the [[Cold War]] with the production of ''[[Sleeping Beauty (1959 film)|Sleeping Beauty]]''.<ref>{{Harvnb|Zipes|1988|p=25}}</ref> The Grimms' tales have provided much of the early foundation on which the Disney empire was built.<ref name = "NG"/> In film, the Cinderella [[Motif (folkloristics)|motif]], the story of a poor girl finding love and success, continues to be repeated in movies such as ''[[Pretty Woman]]'', ''[[Ever After]]'', ''[[Maid in Manhattan]]'', and ''[[Ella Enchanted (film)|Ella Enchanted]]''.<ref name="Tnp">{{Harvnb|Tatar|2010}}</ref> |

|||

20th century educators debated the value and influence of teaching stories that include brutality and violence, causing some of the more grim details to be sanitized.<ref name="Z(1988)15ff"/> Dégh writes that some educators believe children should be shielded from cruelty of any form, that stories with a happy ending are fine to teach whereas those that are darker, particularly the legends, might pose more harm. On the other hand some educators and psychologist believe children easily discern the difference between what is a story and what is not and that the tales continue to have value for children.<ref name = "D99ff">{{Harvnb|Dégh|1979|pp=99–101}}</ref> The publication of [[Bruno Bettleheim]]'s 1976 ''[[The Uses of Enchantment]]'' brought a new wave of interest in the stories as children's literature, with an emphasis on the "therapeutic value for children".<ref name="Tnp"/> More popular stories such as "Hansel and Gretel" and "Little Red Riding Hood" have become staples of modern childhood presented in coloring books, puppet shows and cartoons. Other stories, however, have been considered too gruesome and have not made a popular transition.<ref name = "D95ff"/> |

|||

Regardless of the debate, the Grimms' stories have continued to be resilient and popular around the world,<ref name = "D99ff"/> although a recent study in England appears to suggest that parents consider the stories to be overly violent and inappropriate for young children, writes [[Libby Copeland]] for ''[[Slate (magazine)|Slate]]''.<ref>{{cite web|last=Copeland|first=Libby|title=Tales Out of Fashion?|url=http://www.slate.com/articles/double_x/doublex/2012/02/why_i_don_t_want_to_read_fairy_tales_to_my_daughter_.html|work=Slate|accessdate=March 28, 2012}}</ref> |

|||

{{clear}} |

|||

The university library at the Humboldt-Universität Berlin is housed in the Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm Center (Jakob-und-Wilhelm-Grimm-Zentrum).<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ub.hu-berlin.de/locations/jacob-und-wilhelm-grimm-zentrum?set_language=en |title=Jacob-und-Wilhelm-Grimm-Zentrum — Universitaetsbibliothek der HU Berlin |publisher=Ub.hu-berlin.de |date= |accessdate=2012-12-20}}</ref> Among its collections is a large portion of the Grimm Brothers' private library.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ub.hu-berlin.de/about-us/historical-collections/historical-and-special-collections-of-the-library/overview-of-the-historical-and-special-collections-of-the-library/grimm |title=The Grimm Library — Universitaetsbibliothek der HU Berlin |publisher=Ub.hu-berlin.de |date= |accessdate=2012-12-20}}</ref> |

|||

==Influence== |

==Influence== |

||

Revision as of 14:50, 3 June 2013

Frontispiece of first volume of Grimms' Kinder- und Hausmärchen (1812) | |

| Author | Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm |

|---|---|

| Language | German |

| Genre | |

| Publisher | Various |

Publication date | 1812 |

| Publication place | Germany |

| ISBN | n/a Parameter error in {{ISBNT}}: invalid character |

Children's and Household Tales (German: Kinder- und Hausmärchen) is a collection of German fairy tales first published in 1812 by the Grimm brothers, Jacob and Wilhelm. The collection is commonly known in the Anglosphere as Grimm's Fairy Tales (German: Grimms Märchen).

Composition

The first volume of the first edition was published, containing 86 stories; the second volume of 70 stories followed in 1814. For the second edition, two volumes were issued in 1819 and a third in 1822, totalling 170 tales. The third edition appeared in 1837; fourth edition, 1840; fifth edition, 1843; sixth edition, 1850; seventh edition, 1857. Stories were added, and also subtracted, from one edition to the next, until the seventh held 211 tales. All editions were extensively illustrated, first by Philipp Grot Johann and, after his death in 1892, by Robert Leinweber.

The first volumes were much criticized because, although they were called "Children's Tales", they were not regarded as suitable for children, both for the scholarly information included and the subject matter.[1] Many changes through the editions – such as turning the wicked mother of the first edition in Snow White and Hansel and Gretel (shown in original Grimm stories as Hansel and Grethel) to a stepmother, were made with an eye to such suitability. They removed sexual references—such as Rapunzel's innocently asking why her dress was getting tight around her belly, and thus naïvely revealing her pregnancy and the prince's visits to her stepmother—but, in many respects, violence, particularly when punishing villains, was increased.[2]

In 1825 the Brothers published their Kleine Ausgabe or "small edition", a selection of 50 tales designed for child readers. This children's version went through ten editions between 1825 and 1858.

Background

The 19th century rise of romanticism, Romantic nationalism and trends in valuing popular culture revived interest in fairy tales, which had otherwise been in decline since their late-17th century peak.[3] In Germany a popular collection of tales by Johann Karl August Musäus had been published between 1782 and 1787;[4] the Grimms aided the revival with their folklore collection, built on the conviction that a national identity could be found in popular culture and with the common folk (volk). They published tales they decided were a reflection of German cultural identity, but in the first collection they also included the tales of Charles Perrault, published in Paris in 1697, that were written for the literary salons of an aristocratic audience. Scholar Lydia Jean explains that to reconcile Perrault's aristocratic audience with the idea that the tales originated with the common people, a myth was created that Perrault's work, much of which was original, was an "exact reflection of folklore".[3]

Directly influenced by Brentano and von Arnim who edited and adapted the folksongs of Des Knaben Wunderhorn (The Boy's Magic Horn or cornucopia),[4] the brothers began the collection with the purpose of creating a scholarly treatise of traditional stories and of preserving the stories as they had been handed from generation to generation—a practice that was threatened by increased industrialization.[6] Maria Tatar, professor of German studies at Harvard University, explains that it is precisely in the handing from generation to generation, and the genesis in the oral tradition, that gives folk tales an important mutability. Versions of tales differ from region to region, "picking up bits and pieces of local culture and lore, drawing a turn of phrase from a song or another story, and fleshing out characters with features taken from the audience witnessing their performance."[7]

However, as Tatar explains, the Grimms appropriated as uniquely German stories such as "Little Red Riding Hood", which had existed in many versions and regions throughout Europe, because they believed that such stories were reflections of Germanic culture.[5] Furthermore, the brothers saw fragments of old religions and faiths reflected in the stories which they thought continued to exist and survive through the telling of stories.[8]

Methodology

When Jacob returned to Marburg from Paris in 1806, their friend Brentano sought the brothers' help in adding to his collection of folk tales, at which time the brothers began to gather tales in an organized fashion.[9] By 1810 they had produced a manuscript collection of several dozen tales, written after inviting storytellers to their home and transcribing what they heard. These tales were heavily modified in transcription and many had roots in previously written sources.[10] At Brentano's request, they printed and sent him copies of the 53 tales they collected for inclusion in his third volume of Des Knaben Wunderhorn.[11] Brentano either ignored or forgot about the tales, leaving the copies in a church in Alsace where they were found in 1920. Known as the Ölenberg manuscript, it is the earliest extant version of the Grimms' collection, and has become a valuable source to scholars studying the evolution of the Grimms' collection from the time of its inception. The manuscript was published in 1927 and again in 1975.[12]

Although the brothers gained a reputation for collecting tales from peasants, many tales came from middle-class or aristocratic acquaintances. Wilhelm's wife Dortchen Wild and her family, with their nursery maid, told the brothers some of the more well-known tales, such as “Hansel and Gretel” and “Sleeping Beauty”.[13] Wilhelm collected a number of tales after befriending August von Haxthausen, whom he visited in 1811 in Westphalia where he heard stories from von Haxthausen's circle of friends.[14] Several of the storytellers were of Huguenot ancestry, telling tales of French origin such as those told to the Grimms by Marie Hassenpflug, an educated woman of French Huguenot ancestry,[10] and it is probable that these informants were familiar with Perrault’s Histoires ou contes du temps passé (Stories from Past Times).[3] Other tales were collected from the wife of a middle-class tailor, Dorothea Viehmann, also of French descent. Despite her middle-class background, in the first English translation she was characterized as a peasant and given the name Gammer Gretel.[6]

According to scholars such as Ruth Bottigheimer and Maria Tatar some of the tales probably originated in written form during the medieval period with writers such as Straparola and Boccaccio, but were modified in the 17th century, and again rewritten by the Grimms. Moreover, Tatar writes that the brothers' goal of preserving and shaping the tales as something uniquely German at a time of French occupation was a form of "intellectual resistance", and in so doing they established a methodology for collecting and preserving folklore that set the model to be followed later by writers throughout Europe during periods of occupation.[6]

Writing

From 1807 onward the brothers added to the collection. Jacob established the framework that was maintained through many iterations. By 1815 until his death, Wilhelm assumed sole responsibility for editing and rewriting the tales. Zipes explains that the process of editing included re-composing the tales in a stylistically similar manner, adding dialogue, removing pieces "that might detract from a rustic tone", improving the plots and incorporating psychological motifs.[14] Ronald Murphy writes in The Owl, the Raven, and the Dove that the brothers, and in particular Wilhelm, additionally added religious and spiritual motifs to the tales. He believes that Wilhelm "gleaned" bits of old Germanic faiths, Norse mythology, Roman and Greek mythology and from biblical stories that he reshaped.[8]

Over the years, Wilhelm worked extensively on the prose, expanded and added detail to the stories to the point that many grew to be twice the length as in the earliest published editions.[15] In the later editions Wilhelm polished the language to make it more enticing to a bourgeois audience, eliminated sexual elements, and added Christian elements. After 1819 he began writing for children (children were not initially considered the primary audience), adding entirely new tales or adding new elements that were often strongly didactic to existing tales.[14]

Some changes were made in light of unfavorable reviews, particularly from those who objected that not all the tales were suitable for children because of scenes of violence and sexuality.[16] He worked to modify plots for of the many stories: for example, "Rapunzel" in the first edition of Kinder- und Hausmärchen clearly shows the relationship between the prince and the girl in the tower as sexual, which he edited out in subsequent editions.[15] Tatar writes that morals were added (in the second edition a king's regret was added to the scene in which his wife is burned at the stake), and often the characters in the tale were amended to appear more German: "every fairy (Fee), prince (Prinz) and princess (Prinzessin) (all words of French origin) was transformed into a more Teutonic-sounding enchantress (Zauberin) or wise woman (weise Frau), king's son (Königssohn), king's daughter (Königstochter)."[17]

Themes and analysis

The Grimms' legacy contains legends, novellas and folk stories, the vast majority of which were not intended as children's tales. Deeply concerned by the content of some of the tales—such as those that showed children being eaten—von Armin suggested they be removed. Instead the brothers added an introduction with cautionary advice that parents steer children toward age-appropriate stories. Despite von Armin's unease, none of the tales were eliminated from the collection, in the brothers' belief that all the tales were of value and reflected inherent cultural qualities. Furthermore, the stories were didactic in nature at a time when discipline relied on fear, according to scholar Linda Dégh, who explains that tales such as "Little Red Riding Hood" and "Hansel and Gretel" were written to be "warning tales" for children.[18]

The stories in Kinder- und Hausmärchen include scenes of violence that have since been sanitized. For example the Grimms' version of "Snow White" ends with the stepmother dancing at Snow White's wedding wearing a pair of red-hot iron shoes that kill her; another story has a servant being pushed into a barrel "studded with sharp nails" and then rolled down the street.[19] The Grimms' version of "The Frog Prince" describes the princess throwing the frog against a wall instead of kissing him. To some extent the cruelty and violence may have been a reflection of medieval culture from which the tales originated, such as scenes of witches burning, as described "The Six Swans".[19]

Tales with a spinning motif are broadly represented in the collection. In her essay "Tale Spinners: Submerged Voices in Grimms' Fairy Tales", children's literature scholar Bottigheimer explains that these stories reflect the degree to which spinning was crucial in the life of women in the 19th century and earlier. Spinning, and particularly the spinning of flax, was commonly performed in the home by women. Although many stories begin by describing the occupation of a main character, as in "There once was a miller", as an occupation spinning is never mentioned, probably because the brothers did not consider it an occupation. Instead, spinning was a communal activity, frequently performed in a Spinnstube (spinning room), a place where women most likely kept the oral traditions alive by telling stories while engaged in tedious work.[20] In the stories, a woman's personality is often reflected by her attitude toward spinning: a wise woman might be a spinster, and Bottigheimer explains the spindle was the symbol of a "diligent, well-ordered womanhood."[21] In some stories, such as "Rumpelstiltskin", spinning is associated with a threat; in others spinning might be avoided by a character who is either too lazy or not accustomed to spinning because of her high social status.[20]

The tales were also criticized for being insufficiently German, which not only influenced the tales the brothers included, but their use of language; whereas scholars such as Heinz Rölleke say the stories are an accurate depiction of German culture, showing "rustic simplicity [and] sexual modesty".[19] German culture is deeply rooted in the forest (wald), a dark dangerous place to be avoided, most particularly the old forests with large oak trees, and yet a place to which Little Red Riding Hood's mother sent her daughter to deliver food to grandmother's house.[19]

Some critics such as Alistair Hauke, use Jungian analysis to say that the deaths of the brothers' father and grandfather are the reason for the Grimms' tendency to idealize and excuse fathers, as well as the predominance of female villains in the tales such as the wicked stepmothers, such as the evil stepmother and stepsisters in "Cinderella", but this disregards the fact that they were collectors, not authors of the tales.[22] Another possible influence can be found in the selection of stories such as "The Twelve Brothers", which mirrors the brothers' family structure of one girl and several brothers overcoming opposition.[23] Zipes believes that a number of the stories show autobiographical elements and that the brothers may have used their work as a "quest" to replace the family life they lost when their father died. The collection includes 41 tales about siblings, which Zipes believes are representative of Jacob and Wilhelm. Many of the sibling stories follow a simple plot in which the characters lose a home, work industriously at a specific task, and in the end find a new home.[24]

Editions

Between 1812 and 1864 Kinder- und Hausmärchen was published 17 times: seven of the "Large edition" (Große Ausgabe) and ten of the "Small edition" (Kleine Ausgabe). The Large editions contained all the tales collected to date, extensive annotations and scholarly notes written by the brothers; the Small editions had only 50 tales and were intended for children. Emil Grimm, Jacob and Wilhelm's younger brother, illustrated the Small editions adding Christian symbolism to the drawings, such as depicting Cinderella's mother as an angel and adding a bible to the bedside table of Little Red Riding Hood's grandmother.[25]

The first volume was published in 1812 with 86 folktales,[13] and a second volume with 70 additional tales was published late in 1814 (dated 1815 on the title page); together the two volumes and their 156 tales are considered the first of the Large (annotated) editions.[26][27] A second expanded edition with 170 tales was published in 1819, followed in 1822 by a volume of scholarly commentary and annotations.[11][16] Five more Large editions were published in 1837, 1840, 1843, 1850 and 1857. The seventh and final edition of 1857 contained 211 tales—200 numbered folk tales and the rest were legends.[11][16][27]

In Germany Kinder- und Hausmärchen was also released in a "popular poster-sized Bilderbogen (broadsides)"[27] format and in single story formats for the more popular tales such as "Hansel and Gretel". Pirated editions became common; the stories were often added to collections by other authors as the tales became a focus of interest for children's book illustrators,[27] with well-known artists such as Arthur Rackham, Walter Crane and Edmund Dulac illustrating the tales; a popular edition that sold well, released in the mid-19th century, included elaborate etchings by George Cruikshank.[28] At the deaths of the brothers, the copyright went to Hermann Grimm (Wilhelm's son) who continued the practice of printing the volumes in expensive and complete editions, however after 1893 when copyright lapsed the stories began to be published in many formats and editions.[27] In the 21st century, Kinder- und Hausmärchen, commonly called Grimms' Fairy Tales in English, is a universally recognized text. Jacob and Wilhelm's collection of stories has been translated to over 160 languages with 120 different editions of the text are available for sale in the US alone.[19]

Philology

During their studies at the University of Marburg the brothers came to see culture as tied to language, and regarded the purest cultural expression in the grammar of a language. For this reason they began to distance themselves from the practices of Brentano and the other romanticists who frequently changed the original oral style of folk tales to fit a literary style that the brothers considered artificial; they believed that the style of the people (the volk) represented a natural and divinely inspired poetry (naturpoesie) as opposed to the kunstpoesie (art poetry) which they thought of as artificially constructed.[29][30] As literary historians and scholars they delved into the origins of stories and attempted to retrieve them from the oral tradition without loss of the original traits of oral language.[29]

The brothers strongly believed the dream of national unity and independence relied on a full knowledge of the cultural past that was reflected in folklore.[30] They worked to discover and crystallize a kind of Germanness in the stories they collected because they believed that folklore contained kernels of ancient mythologies and beliefs, crucial to understanding the essence of German culture,[6] and by examining culture from a philological point-of-view they sought to establish connections between German law, culture, and local beliefs.[29]

The Grimms considered the tales to have origins in traditional Germanic folklore, which they thought had been "contaminated" by later literary tradition.[6] In the shift from the oral tradition to the printed book, tales were translated from regional dialects to Standard German (Hochdeutsch or High German),[31] however, over the course of the many modifications and revisions, the Grimms sought to reintroduce regionalisms, dialects and low German to the tales—to re-introduce the language of the original form of the oral tale.[32]

As early as 1812, they published a version of the Lay of Hildebrand, a 9th-century German heroic song, along with Die beiden ältesten deutschen Gedichte aus dem achten Jahrhundert: Das Lied von Hildebrand und Hadubrand und das Weißenbrunner Gebet, (The Two Oldest German Poems of the Eighth Century: The Song of Hildebrand and Hadubrand and the Wessobrunn Prayer), the earliest known German heroic song.[33]

Between 1816 and 1818 the brothers published a two-volume work titled Deutsche Sagen, (German Legends) consisting of 585 German legends.[26] Jacob undertook most of the work of collecting and editing the legends that he organized according to region and historical (ancient) legends,[34] and which were about real people or events.[33] Meant to be a scholarly work, the historical legends were often taken from secondary sources, interpreted, modified and rewritten, resulting works "that were regarded as trademarks".[34] Although some scholars criticized the Grimm's methodology in collecting and rewriting the legends, conceptually they set an example for legend collections that was to be followed by others throughout Europe. Unlike the collection of folk tales, Deutsche Sagen sold poorly.[34]

Less well-known, is the brothers' monumental scholarly work on a German dictionary, the Deutsches Wörterbuch, which they began in 1838. Not until 1852 did they begin publishing the dictionary in installments.[34] The work on the dictionary could not be finished in their lifetime because in it they gave a history and analysis of each word.[33]

Reception and legacy

Kinder- und Hausmärchen was not an immediate bestseller, but its popularity grew with each edition.[36] The early editions attracted lukewarm critical reviews, generally on the basis that the stories were unappealing to children. The brothers responded with modifications and rewrites in order to increase the book's market appeal to that demographic.[6] By the 1870s the tales had increased greatly in popularity, to the point they were added to the teaching curriculum in Prussia. In the 20th century the work has maintained status as second only to the bible as the most popular book in Germany. Its sales generated a mini-industry of criticism which analyzed the tales folkloric content in the context of literary history, socialism and psychological elements often along Freudian and Jungian lines.[36]

In their research, the brothers made a science of the study of folklore (see folkloristics), generating a model of research that "launched general fieldwork in most European countries",[37] and setting standards for research and analysis of stories and legends that made them pioneers in the field of folklore in the 19th century.[38]

During the Third Reich the Grimms' stories were used to foster nationalism and the Nazi party decreed Kinder- und Hausmärchen was a book each household should own; later in occupied Germany the book was banned for a period.[39] In the US, the 1937 release of Walt Disney's Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs shows the triumph of good over evil, innocence over oppression, according to Zipes: a popular theme that Disney repeated in 1959 during the Cold War with the production of Sleeping Beauty.[40] The Grimms' tales have provided much of the early foundation on which the Disney empire was built.[19] In film, the Cinderella motif, the story of a poor girl finding love and success, continues to be repeated in movies such as Pretty Woman, Ever After, Maid in Manhattan, and Ella Enchanted.[41]

20th century educators debated the value and influence of teaching stories that include brutality and violence, causing some of the more grim details to be sanitized.[36] Dégh writes that some educators believe children should be shielded from cruelty of any form, that stories with a happy ending are fine to teach whereas those that are darker, particularly the legends, might pose more harm. On the other hand some educators and psychologist believe children easily discern the difference between what is a story and what is not and that the tales continue to have value for children.[42] The publication of Bruno Bettleheim's 1976 The Uses of Enchantment brought a new wave of interest in the stories as children's literature, with an emphasis on the "therapeutic value for children".[41] More popular stories such as "Hansel and Gretel" and "Little Red Riding Hood" have become staples of modern childhood presented in coloring books, puppet shows and cartoons. Other stories, however, have been considered too gruesome and have not made a popular transition.[39]

Regardless of the debate, the Grimms' stories have continued to be resilient and popular around the world,[42] although a recent study in England appears to suggest that parents consider the stories to be overly violent and inappropriate for young children, writes Libby Copeland for Slate.[43]

The university library at the Humboldt-Universität Berlin is housed in the Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm Center (Jakob-und-Wilhelm-Grimm-Zentrum).[44] Among its collections is a large portion of the Grimm Brothers' private library.[45]

Influence

The influence of these books was widespread. W. H. Auden praised the collection, during World War II, as one of the founding works of Western culture.[46] The tales themselves have been put to many uses. Hitler praised them as folkish tales showing children with sound racial instincts seeking racially pure marriage partners, and so strongly that the Allied forces warned against them;[47] for instance, Cinderella with the heroine as racially pure, the stepmother as an alien, and the prince with an unspoiled instinct being able to distinguish.[48] Writers who have written about the Holocaust have combined the tales with their memoirs, as Jane Yolen in her Briar Rose.[49]

The work of the Brothers Grimm influenced other collectors, both inspiring them to collect tales and leading them to similarly believe, in a spirit of romantic nationalism, that the fairy tales of a country were particularly representative of it, to the neglect of cross-cultural influence. Among those influenced were the Russian Alexander Afanasyev, the Norwegians Peter Christen Asbjørnsen and Jørgen Moe, the English Joseph Jacobs, and Jeremiah Curtin, an American who collected Irish tales.[50] There was not always a pleased reaction to their collection. Joseph Jacobs was in part inspired by his complaint that English children did not read English fairy tales;[51] in his own words, "What Perrault began, the Grimms completed".

Three individual works of Wilhelm Grimm include Altdänische Heldenlieder, Balladen und Märchen ('Old Danish Heroic Lays, Ballads, and Folktales') in 1811, Über deutsche Runen ('On German Runes') in 1821, and Die deutsche Heldensage ('The German Heroic Legend') in 1829.

On 20 December 2012 the search engine Google honoured the 200th anniversary of the Grimms' Fairy Tales with an interactive Doodle.[52]

List of fairy tales

The code "KHM" stands for Kinder- und Hausmärchen, the original title. All editions from 1812 until 1857 split the stories into two volumes.

Volume 1

- KHM 1: The Frog King, or Iron Heinrich (Der Froschkönig oder der eiserne Heinrich)

- KHM 2: Cat and Mouse in Partnership (Katze und Maus in Gesellschaft)

- KHM 3: Mary's Child (Marienkind)

- KHM 4: The Story of the Youth Who Went Forth to Learn What Fear Was (Märchen von einem, der auszog das Fürchten zu lernen)

- KHM 5: The Wolf and the Seven Young Kids (Der Wolf und die sieben jungen Geißlein)

- KHM 6: Trusty John or Faithful John (Der treue Johannes)

- KHM 7: The Good Bargain (Der gute Handel)

- KHM 8: The Wonderful Musician or The Strange Musician (Der wunderliche Spielmann)

- KHM 9: The Twelve Brothers (Die zwölf Brüder)

- KHM 10: The Pack of Ragamuffins (Das Lumpengesindel)

- KHM 11: Brother and Sister (Brüderchen und Schwesterchen)

- KHM 12: Rapunzel

- KHM 13: The Three Little Men in the Wood (Die drei Männlein im Walde)

- KHM 14: The Three Spinners (Die drei Spinnerinnen)

- KHM 15: Hansel and Gretel (Hänsel und Gretel)

- KHM 16: The Three Snake-Leaves (Die drei Schlangenblätter)

- KHM 17: The White Snake (Die weiße Schlange)

- KHM 18: The Straw, the Coal, and the Bean (Strohhalm, Kohle und Bohne)

- KHM 19: The Fisherman and His Wife (Von dem Fischer und seiner Frau)

- KHM 20: The Valiant Little Tailor (Das tapfere Schneiderlein)

- KHM 21: Cinderella (Aschenputtel)

- KHM 22: The Riddle (Das Rätsel)

- KHM 23: The Mouse, the Bird, and the Sausage (Von dem Mäuschen, Vögelchen und der Bratwurst)

- KHM 24: Mother Hulda (Frau Holle)

- KHM 25: The Seven Ravens (Die sieben Raben)

- KHM 26: Little Red Cap (Rotkäppchen)

- KHM 27: Town Musicians of Bremen (Die Bremer Stadtmusikanten)

- KHM 28: The Singing Bone (Der singende Knochen)

- KHM 29: The Devil With the Three Golden Hairs (Der Teufel mit den drei goldenen Haaren)

- KHM 30: The Louse and the Flea (Läuschen und Flöhchen)

- KHM 31: The Girl Without Hands (Das Mädchen ohne Hände)

- KHM 32: Clever Hans (Der gescheite Hans)

- KHM 33: The Three Languages (Die drei Sprachen)

- KHM 34: Clever Elsie (Die kluge Else)

- KHM 35: The Tailor in Heaven (Der Schneider im Himmel)

- KHM 36: The Wishing-Table, the Gold-Ass, and the Cudgel in the Sack ("Tischchen deck dich, Goldesel und Knüppel aus dem Sack" also known as "Tischlein, deck dich!")

- KHM 37: Thumbling (Daumling) (see also Tom Thumb)

- KHM 38: The Wedding of Mrs. Fox (Die Hochzeit der Frau Füchsin)

- KHM 39: The Elves (Die Wichtelmänner)

- The Elves and the Shoemaker (Erstes Märchen)

- Second Story (Zweites Märchen)

- Third Story (Drittes Märchen)

- KHM 40: The Robber Bridegroom (Der Räuberbräutigam)

- KHM 41: Herr Korbes

- KHM 42: The Godfather (Der Herr Gevatter)

- KHM 43: Frau Trude

- KHM 44: Godfather Death (Der Gevatter Tod)

- KHM 45: Thumbling's Travels (see also Tom Thumb) (Daumerlings Wanderschaft)

- KHM 46: Fitcher's Bird (Fitchers Vogel)

- KHM 47: The Juniper Tree (Von dem Machandelboom)

- KHM 48: Old Sultan (Der alte Sultan)

- KHM 49: The Six Swans (Die sechs Schwäne)

- KHM 50: Little Briar-Rose (see also Sleeping Beauty) (Dornröschen)

- KHM 51: Foundling-Bird (Fundevogel)

- KHM 52: King Thrushbeard (König Drosselbart)

- KHM 53: Little Snow White (Schneewittchen)

- KHM 54: The Knapsack, the Hat, and the Horn (Der Ranzen, das Hütlein und das Hörnlein)

- KHM 55: Rumpelstiltskin (Rumpelstilzchen)

- KHM 56: Sweetheart Roland (Der Liebste Roland)

- KHM 57: The Golden Bird (Der goldene Vogel)

- KHM 58: The Dog and the Sparrow (Der Hund und der Sperling)

- KHM 59: Frederick and Catherine (Der Frieder und das Katherlieschen)

- KHM 60: The Two Brothers (Die zwei Brüder)

- KHM 61: The Little Peasant (Das Bürle)

- KHM 62: The Queen Bee (Die Bienenkönigin)

- KHM 63: The Three Feathers (Die drei Federn)

- KHM 64: Golden Goose (Die goldene Gans)

- KHM 65: All-Kinds-of-Fur (Allerleirauh)

- KHM 66: The Hare's Bride (Häschenbraut)

- KHM 67: The Twelve Huntsmen (Die zwölf Jäger)

- KHM 68: The Thief and His Master (De Gaudeif un sien Meester)

- KHM 69: Jorinde and Joringel (Jorinde und Joringel)

- KHM 70: The Three Sons of Fortune (Die drei Glückskinder)

- KHM 71: How Six Men got on in the World (Sechse kommen durch die ganze Welt)

- KHM 72: The Wolf and the Man (Der Wolf und der Mensch)

- KHM 73: The Wolf and the Fox (Der Wolf und der Fuchs)

- KHM 74: Gossip Wolf and the Fox (Der Fuchs und die Frau Gevatterin)

- KHM 75: The Fox and the Cat (Der Fuchs und die Katze)

- KHM 76: The Pink (Die Nelke)

- KHM 77: Clever Gretel (Die kluge Gretel)

- KHM 78: The Old Man and his Grandson (Der alte Großvater und der Enkel)

- KHM 79: The Water Nixie (Die Wassernixe)

- KHM 80: The Death of the Little Hen (Von dem Tode des Hühnchens)

- KHM 81: Brother Lustig (Bruder Lustig)

- KHM 82: Gambling Hansel (De Spielhansl)

- KHM 83: Hans in Luck (Hans im Glück)

- KHM 84: Hans Married (Hans heiratet)

- KHM 85: The Gold-Children (Die Goldkinder)

- KHM 86: The Fox and the Geese (Der Fuchs und die Gänse)

Volume 2

- KHM 87: The Poor Man and the Rich Man (Der Arme und der Reiche)

- KHM 88: The Singing, Springing Lark (Das singende springende Löweneckerchen)

- KHM 89: The Goose Girl (Die Gänsemagd)

- KHM 90: The Young Giant (Der junge Riese)

- KHM 91: The Gnome (Dat Erdmänneken)

- KHM 92: The King of the Gold Mountain (Der König vom goldenen Berg)

- KHM 93: The Raven (Die Raben)

- KHM 94: The Peasant's Wise Daughter (Die kluge Bauerntochter)

- KHM 95: Old Hildebrand (Der alte Hildebrand)

- KHM 96: The Three Little Birds (De drei Vügelkens)

- KHM 97: The Water of Life (Das Wasser des Lebens)

- KHM 98: Doctor Know-all (Doktor Allwissend)

- KHM 99: The Spirit in the Bottle (Der Geist im Glas)

- KHM 100: The Devil's Sooty Brother (Des Teufels rußiger Bruder)

- KHM 101: Bearskin (Bärenhäuter)

- KHM 102: The Willow-Wren and the Bear (Der Zaunkönig und der Bär)

- KHM 103: Sweet Porridge (Der süße Brei)

- KHM 104: Wise Folks (Die klugen Leute)

- KHM 105: Tales of the Paddock (Märchen von der Unke)

- KHM 106: The Poor Miller's Boy and the Cat (Der arme Müllersbursch und das Kätzchen)

- KHM 107: The Two Travelers (Die beiden Wanderer)

- KHM 108: Hans My Hedgehog (Hans mein Igel)

- KHM 109: The Shroud (Das Totenhemdchen)

- KHM 110: The Jew Among Thorns (Der Jude im Dorn)

- KHM 111: The Skillful Huntsman (Der gelernte Jäger)

- KHM 112: The Flail from Heaven (Der Dreschflegel vom Himmel)

- KHM 113: The Two Kings' Children (Die beiden Königskinder)

- KHM 114: The Clever Little Tailor (vom klugen Schneiderlein)

- KHM 115: The Bright Sun Brings it to Light (Die klare Sonne bringt's an den Tag)

- KHM 116: The Blue Light (Das blaue Licht)

- KHM 117: The Willful Child (Das eigensinnige Kind)

- KHM 118: The Three Army Surgeons (Die drei Feldscherer)

- KHM 119: The Seven Swabians (Die sieben Schwaben)

- KHM 120: The Three Apprentices (Die drei Handwerksburschen)

- KHM 121: The King's Son Who Feared Nothing (Der Königssohn, der sich vor nichts fürchtete)

- KHM 122: Donkey Cabbages (Der Krautesel)

- KHM 123: The Old Woman in the Wood (Die alte im Wald)

- KHM 124: The Three Brothers (Die drei Brüder)

- KHM 125: The Devil and His Grandmother (Der Teufel und seine Großmutter)

- KHM 126: Ferdinand the Faithful and Ferdinand the Unfaithful (Ferenand getrü und Ferenand ungetrü)

- KHM 127: The Iron Stove (Der Eisenofen)

- KHM 128: The Lazy Spinner (Die faule Spinnerin)

- KHM 129: The Four Skillful Brothers (Die vier kunstreichen Brüder)

- KHM 130: One-Eye, Two-Eyes, and Three-Eyes (Einäuglein, Zweiäuglein und Dreiäuglein)

- KHM 131: Fair Katrinelje and Pif-Paf-Poltrie (Die schöne Katrinelje und Pif Paf Poltrie)

- KHM 132: The Fox and the Horse (Der Fuchs und das Pferd)

- KHM 133: The Shoes that were Danced to Pieces (Die zertanzten Schuhe)

- KHM 134: The Six Servants (Die sechs Diener)

- KHM 135: The White and the Black Bride (Die weiße und die schwarze Braut)

- KHM 136: Iron John (Eisenhans)

- KHM 137: The Three Black Princesses (De drei schwatten Prinzessinnen)

- KHM 138: Knoist and his Three Sons (Knoist un sine dre Sühne)

- KHM 139: The Maid of Brakel (Dat Mäken von Brakel)

- KHM 140: My Household (Das Hausgesinde)

- KHM 141: The Lambkin and the Little Fish (Das Lämmchen und das Fischchen)

- KHM 142: Simeli Mountain (Simeliberg)

- KHM 143: Going a Traveling (Up Reisen gohn) appeared in the 1819 edition

- KHM 143 in the 1812/1815 edition was Die Kinder in Hungersnot (the starving children)

- KHM 144: The Donkey (Das Eselein)

- KHM 145: The Ungrateful Son (Der undankbare Sohn)

- KHM 146: The Turnip (Die Rübe)

- KHM 147: The Old Man Made Young Again (Das junggeglühte Männlein)

- KHM 148: The Lord's Animals and the Devil's (Des Herrn und des Teufels Getier)

- KHM 149: The Beam (Der Hahnenbalken)

- KHM 150: The Old Beggar-Woman (Die alte Bettelfrau)

- KHM 151: The Twelve Idle Servants (Die zwölf faulen Knechte)

- KHM 151: The Three Sluggards (Die drei Faulen)

- KHM 152: The Shepherd Boy (Das Hirtenbüblein)

- KHM 153: The Star Money (Die Sterntaler)

- KHM 154: The Stolen Farthings (Der gestohlene Heller)

- KHM 155: Looking for a Bride (Die Brautschau)

- KHM 156: The Hurds (Die Schlickerlinge)

- KHM 157: The Sparrow and his Four Children (Der Sperling und seine vier Kinder)

- KHM 158: The Story of Schlauraffen Land (Das Märchen vom Schlaraffenland)

- KHM 159: The Ditmars Tale of Wonders (Das dietmarsische Lügenmärchen)

- KHM 160: A Riddling Tale (Rätselmärchen)

- KHM 161: Snow-White and Rose-Red (Schneeweißchen und Rosenrot)

- KHM 162: The Wise Servant (Der kluge Knecht)

- KHM 163: The Glass Coffin (Der gläserne Sarg)

- KHM 164: Lazy Henry (Der faule Heinz)

- KHM 165: The Griffin (Der Vogel Greif)

- KHM 166: Strong Hans (Der starke Hans)

- KHM 167: The Peasant in Heaven (Das Bürli im Himmel)

- KHM 168: Lean Lisa (Die hagere Liese)

- KHM 169: The Hut in the Forest (Das Waldhaus)

- KHM 170: Sharing Joy and Sorrow (Lieb und Leid teilen)

- KHM 171: The Willow-Worn (Der Zaunkönig)

- KHM 172: The Sole (Die Scholle)

- KHM 173: The Bittern and the Hoopoe (Rohrdommel und Wiedehopf)

- KHM 174: The Owl (Die Eule)

- KHM 175: The Moon (Der Mond)

- KHM 176: The Duration of Life (Die Lebenszeit)

- KHM 177: Death's Messengers (Die Boten des Todes)

- KHM 178: Master Pfreim (Meister Pfriem)

- KHM 179: The Goose-Girl at the Well (Die Gänsehirtin am Brunnen)

- KHM 180: Eve's Various Children (Die ungleichen Kinder Evas)

- KHM 181: The Nixie of the Mill-Pond (Die Nixe im Teich)

- KHM 182: The Little Folk's Presents (Die Geschenke des kleinen Volkes)

- KHM 183: The Giant and the Tailor (Der Riese und der Schneider)

- KHM 184: The Nail (Der Nagel)

- KHM 185: The Poor Boy in the Grave (Der arme Junge im Grab)

- KHM 186: The True Bride (Die wahre Braut)

- KHM 187: The Hare and the Hedgehog (Der Hase und der Igel)

- KHM 188: Spindle, Shuttle, and Needle (Spindel, Weberschiffchen und Nadel)

- KHM 189: The Peasant and the Devil (Der Bauer und der Teufel)

- KHM 190: The Crumbs on the Table (Die Brosamen auf dem Tisch)

- KHM 191: The Sea-Hare (Das Meerhäschen)

- KHM 192: The Master Thief (Der Meisterdieb)

- KHM 193: The Drummer (Der Trommler)

- KHM 194: The Ear of Corn (Die Kornähre)

- KHM 195: The Grave-Mound (Der Grabhügel)

- KHM 196: Old Rinkrank (Oll Rinkrank)

- KHM 197: The Crystal Ball (Die Kristallkugel)

- KHM 198: Maid Maleen (Jungfrau Maleen)

- KHM 199: The Boots of Buffalo Leather (Der Stiefel von Büffelleder)

- KHM 200: The Golden Key (Der goldene Schlüssel)

The children's legends (Kinder-legende) first appeared in the G. Reimer 1819 edition at the end of volume 2).

- KHM 201: Saint Joseph in the Forest (Der heilige Joseph im Walde)

- KHM 202: The Twelve Apostles (Die zwölf Apostel)

- KHM 203: The Rose (Die Rose)

- KHM 204: Poverty and Humility Lead to Heaven (Armut und Demut führen zum Himmel)

- KHM 205: God's Food (Gottes Speise)

- KHM 206: The Three Green Twigs (Die drei grünen Zweige)

- KHM 207: The Blessed Virgin's Little Glass (Muttergottesgläschen) or Our Lady's Little Glass

- KHM 208: The Little Old Lady (Das alte Mütterchen) or The Aged Mother

- KHM 209: The Heavenly Marriage (Die himmlische Hochzeit) or The Heavenly Wedding

- KHM 210: The Hazel Branch (Die Haselrute)

No longer included in last edition

- Das Birnli will nit fallen

- Blaubart (Bluebeard)

- Die drei Schwestern (The Three Sisters)

- Die Prinzessin auf der Erbse (Princess and the Pea)

- Der Faule und der Fleißige (The sluggard and the diligent)

- Der gestiefelte Kater (Puss in Boots)

- Der gute Lappen (Fragment) (The good rag)

- Die Hand mit dem Messer (The hand with the knife)

- Hans Dumm

- Die heilige Frau Kummernis (The holy woman Kummernis)

- Hurleburlebutz

- Die Krähen (The Crows)

- Der Löwe und der Frosch (The Lion and the Frog)

- Das Mörderschloss (The Murder Castle)

- Der Okerlo (The Okerlo)

- Prinzessin Mäusehaut (Princess Mouse Skin)

- Der Räuber und seine Söhne (The Robber and His Sons)

- Schneeblume (Snow Flowers)

- Der Soldat und der Schreiner (The Soldier and the Carpenter)

- Der Tod und der Gänsehirt (Death and the Goose herder)

- Die treuen Tiere (The faithful animals)

- Das Unglück (The Accident)

- Vom Prinz Johannes (Fragment) (Of Prince Johannes)

- Vom Schreiner und Drechsler (From the Maker and Turner)

- Von der Nachtigall und der Blindschleiche (The nightingale and the slow worm)

- Von der Serviette, dem Tornister, dem Kanonenhütlein und dem Horn (Of the napkin, the knapsack, the Cannon guarding flax, and the Horn)

- Wie Kinder miteinander Schlachten gespielt haben (How children played slaughter with each other)

- Der wilde Mann (The Wild Man)

- Die wunderliche Gasterei (The strange Inn)

References

- ^ Maria Tatar, The Hard Facts of the Grimms' Fairy Tales, p15-17, ISBN 0-691-06722-8

- ^ A. S. Byatt, "Introduction" p. xlii-iv, Maria Tatar, ed. The Annotated Brothers Grimm, ISBN 0-393-05848-4

- ^ a b c d Jean 2007, pp. 280–282

- ^ a b Haase 2008, p. 138

- ^ a b Tatar 2004, pp. xxxviii

- ^ a b c d e f Tatar 2004, pp. xxxiv–xxxviii

- ^ Tatar 2004, pp. xxxvi

- ^ a b Murphy 2000, pp. 3–4

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Z(1988)2ffwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Haase 2008, p. 579

- ^ a b c Cite error: The named reference

Pittwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Zipes 2000, p. 62

- ^ a b Joosen 2006, pp. 177–179

- ^ a b c Zipes 1988, pp. 11–14

- ^ a b Tatar 2004, pp. xi–xiii

- ^ a b c Tatar 1987, pp. 15–17

- ^ Tatar 1987, p. 31

- ^ a b Dégh 1979, pp. 91–93

- ^ a b c d e f O'Neill, Thomas. "Guardians of the Fairy Tale: The Brothers Grimm". National Geographic. National Geographic Society. Retrieved March 18, 2012.

- ^ a b Bottigheimer 1982, pp. 142–146

- ^ Bottigheimer 1982, p. 143

- ^ Alister & Hauke 1998, pp. 216–219

- ^ Tatar 2004, p. 37

- ^ Zipes 1988, pp. 39–42

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Z218ffwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Michaelis-Jena 1970, p. 84

- ^ a b c d e Zipes 2000, pp. 276–278

- ^ Haase 2008, p. 73

- ^ a b c Zipes 1988, pp. 32–35

- ^ a b Dégh 1979, pp. 84–85

- ^ Zipes 1994, p. 14

- ^ Robinson 2004, pp. 47–49

- ^ a b c Cite error: The named reference

Hettingwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c d Haase 2008, pp. 429–431

- ^ Deutsche Bundesbank (Hrsg.): Von der Baumwolle zum Geldschein. Eine neue Banknotenserie entsteht. 2. Auflage. Verlag Fritz Knapp GmbH, Frankfurt am Main 1996, ISBN 3-611-00222-4, S. 103.

- ^ a b c Zipes 1988, pp. 15–17

- ^ Dégh 1979, p. 87

- ^ Zipes & 1981 163

- ^ a b Dégh 1979, pp. 94–96

- ^ Zipes 1988, p. 25

- ^ a b Tatar 2010

- ^ a b Dégh 1979, pp. 99–101

- ^ Copeland, Libby. "Tales Out of Fashion?". Slate. Retrieved March 28, 2012.

- ^ "Jacob-und-Wilhelm-Grimm-Zentrum — Universitaetsbibliothek der HU Berlin". Ub.hu-berlin.de. Retrieved 2012-12-20.

- ^ "The Grimm Library — Universitaetsbibliothek der HU Berlin". Ub.hu-berlin.de. Retrieved 2012-12-20.

- ^ A. S. Byatt, "Introduction" p. xxx, Maria Tatar, ed. The Annotated Brothers Grimm, ISBN 0-393-05848-4

- ^ A. S. Byatt, "-xxxix, Maria Tatar, ed. The Annotated Brothers Grimm, ISBN 0-393-05848-4

- ^ Lynn H. Nicholas, Cruel World: The Children of Europe in the Nazi Web p 77-8 ISBN 0-679-77663-X

- ^ A. S. Byatt, "Introduction" p. xlvi, Maria Tatar, ed. The Annotated Brothers Grimm, ISBN 0-393-05848-4

- ^ Jack Zipes, The Great Fairy Tale Tradition: From Straparola and Basile to the Brothers Grimm, p 846, ISBN 0-393-97636-X

- ^ Maria Tatar, p 345-5, The Annotated Classic Fairy Tales, ISBN 0-393-05163-3

- ^ interactive Google Doodle on the occasion of the 200th birthday of the Grimms' Fairy Tales

- Grimm Brothers. The Complete Grimm's Fairy Tales. New York: Pantheon Books, 1944. ISBN 0394494156. (in English, based on Margarate Hunt's translation)

External links

- SurLaLune Fairy Tale site on the Grimms featuring English translations of the Grimms' notes

- Selection of Grimm Fairy Tales in English and German

- Grimm's Tales at Gutenberg Project

- Grimm family and publication timeline

- Grimm's Fairy Tales, English text

- The Grimm Brothers' Children's and Household Tales classified by Aarne-Thompson type

- 200th Anniversary of Grimms' fairy tales, commemorative Google Doodle.

- Grimm's Fairy Tale National Geographic

- Free MP3's of the tales, in German and English

- Complete collection of Grimms' Fairy Tales, early English version

- Grimm's fairy tales The complete collection of Grimm's Household Tales along with alternative translations.

- Grimmstories.com All Grimm's Fairy Tales available freely in English, German, Dutch, Spanish, Danish, Italian and French.

- Grimm's Fairy Tales Collection hosted by the Baldwin Library of Historical Children's Literature at the University of Florida