Virginia-class submarine: Difference between revisions

No edit summary Tag: Possible vandalism |

m Undid revision 607252915 by 209.59.75.114 (talk) I've reverted obvious vandalism; beyond that the vandal messed up the formatting. |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{DISPLAYTITLE:''Virginia''-class submarine}} |

|||

CRAMER HUGGINS IS AN ASSS |

|||

{|{{Infobox ship begin}} |

|||

|+''Virginia''-class |

|||

{{Infobox ship image |

|||

|Ship image=[[File:US Navy 040730-N-1234E-002 PCU Virginia (SSN 774) returns to the General Dynamics Electric Boat shipyard.jpg|border|300px|USS ''Virginia'' (SSN-774)]] |

|||

|Ship caption=The USS ''Virginia'' underway in [[Portsmouth, Virginia]] (August 2004) |

|||

}} |

|||

{{Infobox ship class overview |

|||

|Name=''Virginia'' |

|||

|Builders=[[General Dynamics Electric Boat]]<br />[[Newport News Shipbuilding and Drydock Company]] |

|||

|Operators={{navy|USA}} |

|||

|Class before={{sclass|Seawolf|submarine|5}}-class attack submarine |

|||

|Class after= |

|||

|Subclasses= |

|||

|Cost=$2,707.1m per unit (FY2014)<ref>{{cite web | first=Ronald | last=O'Rourke | title= Navy Virginia (SSN-774) Class Attack Submarine Procurement: Background and Issues for Congress | url=http://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/weapons/RL32418.pdf | format=PDF | date=28 June 2013 | publisher=Congressional Research Service | page=7}} The USN's budget request for two Virginias in financial year 2014 (FY2014) is US$5,414.2 million, including $1,530.8m of advance funding from previous years.</ref><br />$50 million per unit (annual operating cost)<ref>{{cite web |

|||

|url=http://www.onlineopinion.com.au/view.asp?article=14311 |

|||

|title=Facts favour nuclear-powered submarines |

|||

|first=Simon |last=Cowan |

|||

|date=5 November 2012 |

|||

|accessdate=2012-11-09 |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

|Built range=2000-present |

|||

|In service range= |

|||

|In commission range=2004-present |

|||

|Total ships building=5<ref name="ssn787" /> |

|||

|Total ships planned=30<ref name="jeffhead1">{{cite web|url=http://www.jeffhead.com/usn21/nssn.htm |title=US Navy 21st Century - SSN Virginia Class |publisher=Jeffhead.com |date= |accessdate=2013-02-25}}</ref><ref name="submarinesuppliers2">{{cite web|url=http://www.submarinesuppliers.org/programs/index.php |title=Submarine Industrial Base Council |publisher=Submarinesuppliers.org |date=2008-12-22 |accessdate=2013-02-25}}</ref> (see text) |

|||

|Total ships completed=10 |

|||

|Total ships cancelled= |

|||

|Total ships active=10 |

|||

|Total ships laid up= |

|||

|Total ships lost= |

|||

|Total ships retired= |

|||

|Total ships preserved= |

|||

}} |

|||

{{Infobox ship characteristics |

|||

|Hide header= |

|||

|Header caption= |

|||

|Ship type=[[Attack submarine]] |

|||

|Ship displacement={{convert|7900|t|LT|sp=us}} |

|||

|Ship length={{convert|377|ft|m|0|abbr=on}} |

|||

|Ship beam={{convert|34|ft|m|0|abbr=on}} |

|||

|Ship height= |

|||

|Ship draft= |

|||

|Ship depth= |

|||

|Ship decks= |

|||

|Ship deck clearance= |

|||

|Ship power= |

|||

|Ship propulsion=[[S9G reactor]] {{convert|40000|shp|abbr=on|lk=in}} |

|||

|Ship speed= 30-35 knots or over |

|||

|Ship range=unlimited |

|||

|Ship endurance=unlimited except by food supplies |

|||

|Ship test depth= +{{convert|800|ft|m|abbr=on}} |

|||

|Ship complement=135 (15:120) |

|||

|Ship sensors= |

|||

|Ship EW= |

|||

|Ship armament=12 × [[Vertical Launching System|VLS]] ([[BGM-109]] Tomahawk cruise missile) tubes<br/> |

|||

4 × 533mm torpedo tubes ([[Mark 48 torpedo|Mk-48 torpedo]]) |

|||

27 × torpedoes & missiles (torpedo room)<ref name="cbo"> |

|||

{{cite web |

|||

|url=http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/07-25-12-NavyShipbuilding_0.pdf |

|||

|title=An Analysis of the Navy's Fiscal Year 2013 Shipbuilding Plan |

|||

|format=PDF |

|||

|publisher=[[Congressional Budget Office]] |

|||

|date=July 2012 |

|||

|accessdate=2012-10-17 |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

|Ship notes= |

|||

}} |

|||

|} |

|||

The '''''Virginia''-class''', also known as the '''SSN-774-class''', is a class of [[Nuclear marine propulsion|nuclear-powered]] fast [[attack submarine|attack]] [[submarine]]s ([[SSK (US Navy)|hull classification symbol]] SSN) in service with the [[United States Navy]]. The submarines are designed for a broad spectrum of [[Blue-water navy|open-ocean]] and [[littoral]] missions. They were conceived as a less expensive alternative to the [[Seawolf class submarine|''Seawolf''-class attack submarines]], designed during the [[Cold War]] era, and they are planned to replace the older of the [[Los Angeles class submarine|''Los Angeles''-class submarines]], twenty of which have already been decommissioned (from a total of 62 built). The class was developed under the codename '''Centurion''', renamed to NSSN (New SSN) later on.<ref name="SSN-774 Virginia class">{{cite web |

|||

|url=http://www.harpoondatabases.com/encyclopedia/Entry1383.aspx |

|||

|title=SSN-774 Virginia class |

|||

|accessdate=2012-11-23 |

|||

}}</ref> The "Centurion Study" was initiated in February 1991.<ref> |

|||

{{cite web |

|||

|url=http://www.fas.org/man//dod-101/sys/ship/docs/920721-cr.htm |

|||

|title=Navy Report on New Attack Submarine (Senate - July 21, 1992) |

|||

|publisher=[[Federation of American Scientists]] |

|||

|accessdate=2012-12-15 |

|||

}}</ref> ''Virginia''-class submarines will be acquired through 2043, and are expected to remain in service past 2060.<ref>[http://defensetech.org/2014/02/12/navy-considers-future-after-virginia-class-subs/ Navy Considers Future After Virginia-Class Subs] - Defensetech.org, 12 February 2014</ref> |

|||

== Innovations == |

|||

The ''Virginia'' class incorporates several innovations not previously incorporated into other submarine classes.<ref name="baker1005">{{cite book |title=Combat Fleets of the World, 1998–1999 |last= Baker|first=A. D. III |year=1998 |location= USA|isbn= 1-55750-111-4|page=1005 |url= }}</ref> |

|||

=== Photonics masts === |

|||

Instead of a traditional [[periscope]], the class utilizes a pair of [[AN/BVS-1]] telescoping [[photonics mast]]s<ref name="baker1005" /> located outside the [[pressure hull]]. Each mast contains high-[[image resolution|resolution]] cameras, along with light-intensification and [[infrared camera|infrared sensors]], an infrared [[laser rangefinder]], and an integrated [[Electronic Support Measures]] (ESM) array. Signals from the masts' sensors are transmitted through [[fiber optic]] data lines through [[signal processor]]s to the control center. Visual feeds from the masts are displayed on [[LCD]] interfaces in the command center.<ref name="autogeneratedmil">{{cite web|url=http://www.navy.mil/navydata/cno/n87/usw/winter99/virginia_class.htm |title=Virginia Class |publisher=Navy.mil |date= |accessdate=2013-02-06}}</ref> |

|||

=== Propulsor === |

|||

In contrast to a traditional bladed propellor, the ''Virginia'' class uses [[pump-jet]] propulsors (built by [[BAE Systems]]),<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.baesystems.com/article/BAES_049643/bae-systems-delivers-first-us-navy-submarine-propulsor-from-louisville-facility-receives-additional-243-million-contract |title=Newsroom |publisher=BAE Systems |date= |accessdate=2013-07-26}}</ref> originally developed for the [[Royal Navy]]'s [[Swiftsure-class submarine|''Swiftsure'' class submarines]].<ref> |

|||

{{cite book |

|||

|last=Hool |

|||

|first=Jack |

|||

|last2=Nutter |

|||

|first2=Keith |

|||

|title=Damned Un-English Machines, a history of Barrow-built submarines |

|||

|publisher=Tempus |

|||

|year=2003 |

|||

|isbn=0-7524-2781-4 |

|||

|page=180 |

|||

}}</ref> The propulsor significantly reduces the risks of [[cavitation]], and allows quieter operation. |

|||

=== Improved sonar systems === |

|||

''Virginia'' class submarines are equipped with a bow-mounted spherical active/passive sonar array, a wide aperture lightweight fiber optic sonar array (three flat panels mounted low along either side of the hull), as well as two high frequency active sonars mounted in the sail and keel (under the bow). The submarines are also equipped with a low frequency towed sonar array and a high frequency towed sonar array.<ref name="military.com">{{cite web |url=http://tech.military.com/equipment/view/138675/ssn774-virginia-class-fast-attack-submarine.html |title=SSN774 Virginia-class Fast Attack Submarine |publisher=Tech.military.com |accessdate=2012-09-30}}</ref> The chin-mounted (below the bow) high frequency sonar supplements the (spherical/LAB) main sonar array enabling safer operations in coastal waters as well as improving ASW performance.<ref> |

|||

{{cite web |

|||

|url=http://www.ultra-os.com/special.php |

|||

|title=Special Purpose Sonar |

|||

|publisher=Ultra Electronics Ocean Systems |

|||

|accessdate=2021-12-15 |

|||

}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |

|||

|url=http://www.navy.mil/navydata/cno/n87/usw/issue_3/uss_asheville.htm |

|||

|title=USS ''Asheville'' Leads the Way in High Frequency Sonar |

|||

|work=Undersea Warfare Magazine |

|||

|volume=1 |

|||

|issue=3 |

|||

|year=1999 |

|||

|first=Leonard, LTJG |

|||

|last=Moreavek |

|||

|first2=T.J |

|||

|last2=Brudner |

|||

|accessdate=2012-12-15 |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

The {{USS|California|SSN-781|6}} was the first ''Virginia''-class submarine with the advanced electromagnetic signature reduction system built into it, but this system is being retrofitted into the other submarines of the class.<ref> |

|||

{{cite web |

|||

|url=http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d09326sp.pdf |

|||

|title=GAO-09-326SP |

|||

|format=PDF |

|||

|publisher=[[Government Accounting Office]] |

|||

|date= |

|||

|accessdate=2012-11-23 |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

=== Other improved equipment === |

|||

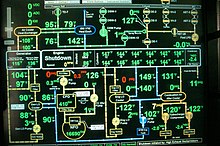

[[File:US Navy 040822-N-2653P-344 One of PCU Virginia's (SSN 774) new components is it's diesel generator, a Caterpillar 3512B V-12 Twin-turbo charged engine.jpg|thumb|Virginia Class Diesel Generator Control Panel]] |

|||

* [[Fiber optic]] [[fly-by-wire]] '''Ship Control System''' replaces electro-hydraulic systems for control surface actuation. |

|||

* Command and control system module (CCSM) built by Lockheed Martin.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.navy.mil/navydata/cno/n87/usw/issue_11/pcu_virginia.html |title=PCU Virginia (SSN-774) |publisher=Navy.mil |date=2000-05-15 |accessdate=2013-02-06}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.naval-technology.com/projects/nssn/ |title=NSSN Virginia Class Attack Submarine |publisher=Naval Technology |date=2011-06-15 |accessdate=2013-02-06}}</ref> |

|||

* Modernized version of the AN/BSY-1 integrated combat system<ref name="SSN-774 Virginia class"/> designated AN/BYG-1 (previously designated CCS Mk2) and built by General Dynamics AIS (previously Raytheon).<ref>{{cite web|url=http://raytheon.mediaroom.com/index.php?s=43&item=360 |title=Raytheon News Release Archive |publisher=Raytheon.mediaroom.com |date=2006-01-30 |accessdate=2013-02-06}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.defenseindustrydaily.com/General-Dynamics-To-Upgrade-Submarine-Weapons-Control-Systems-05631/|title=General Dynamics To Upgrade Submarine Weapons Control Systems|first=|last=|date=July 21, 2009|work=Defense Industry Daily|accessdate=November 12, 2013}}</ref> AN/BYG-1 integrates the submarine Tactical Control System (TCS) and Weapon Control System (WCS).<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.gd-ais.com/Domains/ANBYG-1-Submarine-Tactical-Control-System-(TCS) |title=AN/BYG-1 Submarine Tactical Control System (TCS) |publisher=Gd-ais.com |date= |accessdate=2013-02-06}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.militaryaerospace.com/articles/2013/06/gd-cots-submarine.html |title=General Dynamics continues project to upgrade submarine electronics with COTS computers - Military & Aerospace Electronics |publisher=Militaryaerospace.com |date=2013-06-27 |accessdate=2013-07-26}}</ref> |

|||

* Integral 9-man lock-out chamber.<ref name="aticourses"> |

|||

{{cite web |

|||

|url=http://www.aticourses.com/blog/index.php/2011/07/19/uss-virginia-ssn-774a-new-steel-shark-at-sea/ |

|||

|title=USS Virginia SSN-774-A New Steel Shark at Sea |

|||

|publisher=Applied Technology Institute |

|||

|accessdate=2021-12-15 |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

==History== |

|||

''Virginia'' class submarines were the first US Navy warships designed with the help of computer-aided design (CAD) and visualization technology.<ref name="autogeneratedmil"/><ref name="submarinesuppliers1">{{cite web|url=http://www.submarinesuppliers.org/programs/index.php |title=Submarine Industrial Base Council |publisher=Submarinesuppliers.org |date=2008-12-22 |accessdate=2013-02-06}}</ref> |

|||

Around 9 million work hours are required for the completion of a single ''Virginia'' class submarine.<ref name="submarinesuppliers1"/><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.navalsubleague.com/NSL/default.aspx |title=Naval Submarine League |publisher=Navalsubleague.com |date=2012-09-27 |accessdate=2013-02-06}}</ref><ref name="navalsubleague1">http://www.navalsubleague.com/NSL/documents/Submarine%20Road%20Show%20NSL%2017%20Aug%202011%20NSL.ppsx</ref> Over 4,000 suppliers are involved in the construction of the ''Virginia'' class.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.public.navy.mil/subfor/underseawarfaremagazine/Issues/Archives/issue_43/double_vision.html|title=Double Vision: Planning to Increase Virginia-Class Production|first=Jim|last=Roberts|year=2011|work=Undersea Warfare|accessdate=November 12, 2013}}</ref> Each submarine is projected to make 14-15 deployments during its 33-year service life.<ref>{{cite web|last=Admiral |first=Rear |url=http://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2011-06/sweet-smell-acquisition-success |title=The Sweet Smell of Acquisition Success | U.S. Naval Institute |publisher=Usni.org |date= |accessdate=2013-03-15}}</ref> |

|||

The ''Virginia''-class was intended, in part, as a cheaper ($1.8 billion vs $2.8 billion) alternative to the [[Seawolf class submarine|''Seawolf''-class submarines]], whose production run was stopped after just three boats had been completed. To reduce costs, the ''Virginia''-class submarines use many "[[commercial off-the-shelf]]" (or COTS) components, especially in their computers and data networks. In practice, they actually cost less than $1.8 billion (in fiscal year 2009 dollars) each, due to improvements in shipbuilding technology.<ref name="baker1005" /> |

|||

In hearings before both [[U.S. House of Representatives|House of Representatives]] and [[U.S. Senate|Senate]] committees, the [[Congressional Research Service]] (CRS) and expert witnesses testified that the current procurement plans of the ''Virginia''-class – one per year at present, accelerating to two per year beginning in 2012 – would result in high unit costs and (according to some of the witnesses and to some of the committee chairmen) an insufficient number of attack submarines.<ref name="fas1"> |

|||

{{cite web |

|||

|url=http://www.fas.org/man/congress/2000/00-06-27hunter.htm |

|||

|title=Statement of The Honorable Duncan Hunter, Chairman, Subcommittee on Military Procurement, Submarine Force Structure and Modernization |

|||

|publisher=[[Federation of American Scientists]] |

|||

|work=FAS Military Analysis Network |

|||

|date=27 June 2000 |

|||

|accessdate=2008-03-01 |

|||

}}</ref> In a 10 March 2005 statement to the House Armed Services Committee, Ronald O'Rourke of the CRS testified that, assuming the production rate remains as planned, "production economies of scale for submarines would continue to remain limited or poor."<ref name="orourke1"> |

|||

{{cite web |

|||

|url=http://www.house.gov/hasc/testimony/109thcongress/Projection%20Forces/3-10-05O'RourkeCRS.pdf |

|||

|format=PDF |

|||

|title=Statement of Ronald O'Rourke Specialist in National Defense Congressional Research Service before the House Armed Services Committee Subcommittee on Projection Forces Hearing on Navy Force Architecture and Ship Construction |

|||

|date=10 March 2005 |

|||

|accessdate=2008-03-01 |

|accessdate=2008-03-01 |

||

|archiveurl=http://web.archive.org/web/20060924035407/http://www.house.gov/hasc/testimony/109thcongress/Projection+Forces/3-10-05O'RourkeCRS.pdf |

|archiveurl=http://web.archive.org/web/20060924035407/http://www.house.gov/hasc/testimony/109thcongress/Projection+Forces/3-10-05O'RourkeCRS.pdf |

||

Revision as of 23:50, 5 May 2014

The USS Virginia underway in Portsmouth, Virginia (August 2004)

| |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Name | Virginia |

| Builders | list error: <br /> list (help) General Dynamics Electric Boat Newport News Shipbuilding and Drydock Company |

| Operators | |

| Preceded by | Seawolf-class attack submarine |

| Cost | list error: <br /> list (help) $2,707.1m per unit (FY2014)[1] $50 million per unit (annual operating cost)[2] |

| Built | 2000-present |

| In commission | 2004-present |

| Planned | 30[4][5] (see text) |

| Building | 5[3] |

| Completed | 10 |

| Active | 10 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Attack submarine |

| Displacement | 7,900 metric tons (7,800 long tons) |

| Length | 377 ft (115 m) |

| Beam | 34 ft (10 m) |

| Propulsion | S9G reactor 40,000 shp (30,000 kW) |

| Speed | 30-35 knots or over |

| Range | unlimited |

| Endurance | unlimited except by food supplies |

| Test depth | +800 ft (240 m) |

| Complement | 135 (15:120) |

| Armament | list error: <br /> list (help) 12 × VLS (BGM-109 Tomahawk cruise missile) tubes 4 × 533mm torpedo tubes (Mk-48 torpedo) 27 × torpedoes & missiles (torpedo room)[6] |

The Virginia-class, also known as the SSN-774-class, is a class of nuclear-powered fast attack submarines (hull classification symbol SSN) in service with the United States Navy. The submarines are designed for a broad spectrum of open-ocean and littoral missions. They were conceived as a less expensive alternative to the Seawolf-class attack submarines, designed during the Cold War era, and they are planned to replace the older of the Los Angeles-class submarines, twenty of which have already been decommissioned (from a total of 62 built). The class was developed under the codename Centurion, renamed to NSSN (New SSN) later on.[7] The "Centurion Study" was initiated in February 1991.[8] Virginia-class submarines will be acquired through 2043, and are expected to remain in service past 2060.[9]

Innovations

The Virginia class incorporates several innovations not previously incorporated into other submarine classes.[10]

Photonics masts

Instead of a traditional periscope, the class utilizes a pair of AN/BVS-1 telescoping photonics masts[10] located outside the pressure hull. Each mast contains high-resolution cameras, along with light-intensification and infrared sensors, an infrared laser rangefinder, and an integrated Electronic Support Measures (ESM) array. Signals from the masts' sensors are transmitted through fiber optic data lines through signal processors to the control center. Visual feeds from the masts are displayed on LCD interfaces in the command center.[11]

Propulsor

In contrast to a traditional bladed propellor, the Virginia class uses pump-jet propulsors (built by BAE Systems),[12] originally developed for the Royal Navy's Swiftsure class submarines.[13] The propulsor significantly reduces the risks of cavitation, and allows quieter operation.

Improved sonar systems

Virginia class submarines are equipped with a bow-mounted spherical active/passive sonar array, a wide aperture lightweight fiber optic sonar array (three flat panels mounted low along either side of the hull), as well as two high frequency active sonars mounted in the sail and keel (under the bow). The submarines are also equipped with a low frequency towed sonar array and a high frequency towed sonar array.[14] The chin-mounted (below the bow) high frequency sonar supplements the (spherical/LAB) main sonar array enabling safer operations in coastal waters as well as improving ASW performance.[15][16]

The USS California was the first Virginia-class submarine with the advanced electromagnetic signature reduction system built into it, but this system is being retrofitted into the other submarines of the class.[17]

Other improved equipment

- Fiber optic fly-by-wire Ship Control System replaces electro-hydraulic systems for control surface actuation.

- Modernized version of the AN/BSY-1 integrated combat system[7] designated AN/BYG-1 (previously designated CCS Mk2) and built by General Dynamics AIS (previously Raytheon).[20][21] AN/BYG-1 integrates the submarine Tactical Control System (TCS) and Weapon Control System (WCS).[22][23]

- Integral 9-man lock-out chamber.[24]

History

Virginia class submarines were the first US Navy warships designed with the help of computer-aided design (CAD) and visualization technology.[11][25] Around 9 million work hours are required for the completion of a single Virginia class submarine.[25][26][27] Over 4,000 suppliers are involved in the construction of the Virginia class.[28] Each submarine is projected to make 14-15 deployments during its 33-year service life.[29]

The Virginia-class was intended, in part, as a cheaper ($1.8 billion vs $2.8 billion) alternative to the Seawolf-class submarines, whose production run was stopped after just three boats had been completed. To reduce costs, the Virginia-class submarines use many "commercial off-the-shelf" (or COTS) components, especially in their computers and data networks. In practice, they actually cost less than $1.8 billion (in fiscal year 2009 dollars) each, due to improvements in shipbuilding technology.[10]

In hearings before both House of Representatives and Senate committees, the Congressional Research Service (CRS) and expert witnesses testified that the current procurement plans of the Virginia-class – one per year at present, accelerating to two per year beginning in 2012 – would result in high unit costs and (according to some of the witnesses and to some of the committee chairmen) an insufficient number of attack submarines.[30] In a 10 March 2005 statement to the House Armed Services Committee, Ronald O'Rourke of the CRS testified that, assuming the production rate remains as planned, "production economies of scale for submarines would continue to remain limited or poor."[31]

In 2001, Newport News Shipbuilding and General Dynamics Electric Boat Company built a quarter-scale version of a Virginia class submarine dubbed Large Scale Vehicle II (LSV II) Cutthroat. The vehicle was designed as an affordable test platform for new technologies.[32][33]

The Virginia-class is built through an industrial arrangement designed to keep both GD Electric Boat and Newport News Shipbuilding and Drydock Company (the only two U.S. shipyards capable of building nuclear-powered vessels) in the submarine-building business.[34] Under the present arrangement, the Newport News facility builds the stern, habitability and machinery spaces, torpedo room, sail and bow, while Electric Boat builds the engine room and control room. The facilities alternate work on the reactor plant as well as the final assembly, test, outfit and delivery.

O’Rourke wrote in 2004 that, "Compared to a one-yard strategy, approaches involving two yards may be more expensive but offer potential offsetting benefits."[35] Among the claims of "offsetting benefits" that O'Rourke attributes to supporters of a two-facility construction arrangement is that it "would permit the United States to continue building submarines at one yard even if the other yard is rendered incapable of building submarines permanently or for a sustained period of time by a catastrophic event of some kind", including an enemy attack.

In order to get the submarine's price down to $2 billion per submarine in FY-05 dollars, the Navy instituted a cost-reduction program to shave off approximately $400 million in costs off each submarine's price tag. The project was dubbed "2 for 4 in 12," referring to the Navy's desire to buy two boats for $4 billion in FY-12. Under pressure from Congress, the Navy opted to start buying two boats a year earlier, in FY-11, meaning that officials would not be able to get the $2 billion price tag before the service started buying two submarines per year. However, program manager Dave Johnson said at a conference on 19 March 2008, that the program was only $30 million away from achieving the $2 billion price goal, and would reach that target on schedule.[36]

The Virginia Class Program Office received the David Packard Excellence in Acquisition Award in 1996, 1998, 2008, "for excelling in four specific award criteria: reducing life-cycle costs; making the acquisition system more efficient, responsive, and timely; integrating defense with the commercial base and practices; and promoting continuous improvement of the acquisition process".[37]

In December 2008, the Navy signed a $14 billion contract with General Dynamics and Northrop Grumman to supply eight submarines. The contractors will deliver one submarine in each of fiscal 2009 and 2010, and two submarines on each of fiscal 2011, 2012 and 2013.[38] This contract will bring the Navy's Virginia-class fleet to 18 submarines. And in December 2010, the United States Congress passed a defense authorization bill that expanded production to two subs per year.[39] Two submarine-per-year production resumed on 2 September 2011 with commencement of SSN-787 construction.[3]

On 21 June 2008, the Navy christened New Hampshire (SSN-778), the first Block II submarine. This boat was delivered eight months ahead of schedule and $54 million under budget. Block II boats are built in four sections, compared to the ten sections of the Block I boats. This enables a cost saving of about $300 million per boat, reducing the overall cost to $2 billion per boat and the construction of two new boats per year. Beginning in 2010, new submarines of this class will include a software system that can monitor and reduce their electromagnetic signatures when needed.[40]

The first full duration six month deployment was successfully carried out from October 15, 2009 to April 13, 2010.[41] Authorization of full-rate production and the declaration of full operational capability was achieved five months later.[42] In September 2010, it was found that urethane tiles, applied to the hull to damp internal sound and absorb rather than reflect sonar pulses, were falling off while the subs were at sea.[43] Admiral Kevin McCoy announced that the problems with the Mold-in-Place Special Hull Treatment for the early subs had been fixed in 2011, then the Minnesota was built and found to have the same problem.[44]

Professor Ross Babbage of the Australian National University has called on Australia to buy or lease a dozen Virginia class submarines from the United States, rather than locally build 12 replacements for its Collins class submarines.[45]

In 2013, just as two per year sub construction was supposed to get started, Congress failed to resolve the United States fiscal cliff, forcing the Navy to attempt to "de-obligate" construction funds.[46]

Technology barriers

Because of the low rate of Virginia production, the Navy entered into a program with DARPA to overcome technology barriers to lower the cost of attack submarines so that more could be built, to maintain the size of the fleet.[47]

These include:[48]

- Propulsion concepts not constrained by a centerline shaft.

- Externally stowed and launched weapons (especially torpedoes).

- Conformal alternatives to the existing spherical sonar array.

- Technologies that eliminate or substantially simplify existing submarine hull, mechanical and electrical systems.

- Automation to reduce crew workload for standard tasks

Virginia Payload Module

The Block III submarines have two multipurpose Virginia Payload Tubes(VPT) replacing the dozen single purpose cruise missile launch tubes.[49]

The Block V submarines built from 2019 onward will have an additional Virginia Payload Module (VPM) mid-body section, increasing their overall length. The VPM will add four more VPTs of the same diameter and greater height, located on the centerline, carrying up to seven Tomahawk missiles apiece, that would replace some of the capabilities lost when the SSGN conversion Template:Sclass-s are retired from the fleet.[50][51] Initially eight payload tubes/silos were planned[52] but this was later rejected in favour of 4 tubes installed in a 70 foot long module between the operations compartment and the propulsion spaces.[53][54][55]

The VPM could potentially carry (non-nuclear) medium-range ballistic missiles. Adding the VPM would increase the cost of each submarine by $500 million (2012 prices).[56] This additional cost would be offset by reducing the total submarine force by four ships.[57] More recent reports state that as a cost reduction measure the VPM would carry only Tomahawk SLCM and possibly unmanned undersea vehicles (UUV) with the new price tag now estimated at $360–380 million per boat (in 2010 prices). The VPM launch tubes/silos will reportedly be similar in design to the ones planned for the Ohio class replacement.[58][59] As of September 2013[update] the CNO was still hoping to field the VPM from 2027,[60] but deployment now seems unlikely since JROC moved the program in February 2013 from the Prompt Strike budget to the main Navy shipbuilding account, which is already under financial pressure.[61]

Specifications

- Builders: GD Electric Boat and HII Newport News

- Length: 377 ft (114.91 m)

- Beam: 34 ft (10.36 m)

- Displacement: 7,800 long tons (7,900 t)

- Payload: 40 weapons, special operations forces, unmanned undersea vehicles, Advanced SEAL Delivery System (ASDS)

- Propulsion: The S9G nuclear reactor, 29.8 MW delivering 40,000 shaft horse power.[62] Nuclear core life estimated at 33 years.[63]

- Maximum diving depth: greater than 800 ft (240 m), allegedly around 1,600 feet (490 m)[24]

- Speed: Greater than 25 knots (46 km/h; 29 mph),[64] allegedly up to 34 knots[24][65]

- Planned cost: about US$1.65 billion each (based on FY95 dollars, 30-ship class and two ship/year build-rate)

- Actual cost: US$1.5 billion (in 1994 prices), US$2.6 billion (in 2012 prices)[66][67]

- Crew: 120 enlisted and 14 officers

- Armament: 12 VLS & four torpedo tubes, capable of launching Mark 48 torpedoes, UGM-109 Tactical Tomahawks, Harpoon missiles[68] and the new advanced mobile mine when it becomes available.

- Decoys: Acoustic Device Countermeasure Mk 3/4[69]

Boats

Block I

Modular construction techniques were incorporated during construction.[70] Earlier submarines (e.g. Los Angeles class SSNs) were built by assembling the pressure hull and then installing the equipment via cavities in the pressure hull. This required extensive construction activities within the narrow confines of the pressure hull which was time consuming and dangerous. Modular construction was implemented in an effort to overcome these problems and make the construction process more efficient. Modular construction techniques incorporated during construction include constructing large segments of equipment outside the hull. These segments (dubbed rafts) are then inserted into a hull section (a large segment of the pressure hull). The integrated raft and hull section form a module which when joined with other modules forms a Virginia class submarine.[71] Block I boats were built in 10 modules with each submarine requiring roughly 7 years (84 months) to build.[72]

- USS Virginia (SSN-774), commissioned and in service.

- USS Texas (SSN-775), commissioned and in service.

- USS Hawaii (SSN-776), commissioned and in service.

- USS North Carolina (SSN-777), commissioned and in service.[73]

Block II

Block II boats were built in four sections rather than ten sections, saving about $300 million per boat. Block II boats (excluding SSN-778) were also built under a multi-year procurement agreement as opposed to a block-buy contract in Block I, enabling savings in the range of $400 million ($80 million per boat).[74][75] As a result of improvements in the construction process, New Hampshire (SSN-778) was 500 million USD cheaper, required 3.7 million fewer labor hours to build (25% less) thus shortening the construction period by 15 months (20% less) compared to USS Virginia (SSN-774).[71]

- USS New Hampshire (SSN-778), commissioned and in service.[76]

- USS New Mexico (SSN-779) commissioned and in service.[77][78]

- USS Missouri (SSN-780), commissioned and in service.[79]

- USS California (SSN-781), commissioned and in service.[80]

- USS Mississippi (SSN-782), commissioned and in service.[81]

- USS Minnesota (SSN-783), commissioned and in service.[82]

Block III

SSN-784 through approximately SSN-791 are planned to make up the Third Block or "Flight" and began construction in 2009. Block III subs will feature a revised bow with a Large Aperture Bow (LAB) sonar array, as well as technology from Ohio-class SSGNs (2 VLS tubes each containing 6 missiles).[83] The horseshoe-shaped LAB sonar array will replace the spherical main sonar array which has been used on all U.S. Navy SSNs since 1960.[84][85][86] The LAB sonar array is water-backed as opposed to earlier sonar arrays which were air-backed and consists of a passive array and a medium-frequency active array.[87] Compared to earlier Virginia class submarines about 40% of the bow has been redesigned.[88]

- North Dakota (SSN-784), named 15 July 2008,[89] laid down 11 May 2012,[90] was christened on November 2, 2013.[91] and is scheduled to be commissioned in May 2014.

- John Warner (SSN-785), named 8 January 2009,[92] laid down 16 March 2013,[93] and is contracted for delivery in August 2015.

- Illinois (SSN-786), construction began in March 2011. It is contracted for delivery in August 2016.[94]

- Washington (SSN-787), named 13 April 2012,[95] construction began on 2 Sep 2011.[3]

- Colorado (SSN-788)

- Indiana (SSN-789)

- South Dakota (SSN-790)

- Delaware (SSN-791)

Block IV

The most costly shipbuilding contract in history was awarded on 28 April 2014 as prime contractor General Dynamic Electric Boat took on a $17.6 billion contract for ten Block IV Virginia-class attack submarines. The main improvement over the Block III is the reduction of major maintenance periods from four to three, increasing each ship's total lifetime deployments by one.[96]

The long-lead-time materials contract for SSN 792 was awarded on April 17, 2012, with SSN 793 and SSN 794 following on December 28, 2012.[97][98] the U.S. Navy has awarded General Dynamics Electric Boat a $208.6 million contract modification for the second fiscal year (FY) 14 Virginia-class submarine, SSN-793, and two FY 15 submarines, SSN-794 and SSN-795.With this modification, the overall contract is worth $595 million.[99] Block IV will consist of 9-10 submarines.[100] Based on the planned split between block IV and block V boats, the block IV procurement should comprise the following hull numbers.[101]

Block V

Block V subs may incorporate the Virginia Payload Module (VPM), which would give guided-missile capability when the SSGNs are retired from service.[102]

Future acquisitions

The Navy plans to acquire at least 30 Virginia class submarines,[4][5] however, more recent data provided by the Naval Submarine League (in 2011) and the Congressional Budget Office (in 2012) seems to imply that more than 30 may eventually be built. The Naval Submarine League believes that up to 10 Block V boats will be built.[27][103] The same source also states that 10 additional submarines could be built after Block V submarines, with 5 in the so-called Block VI and 5 in Block VII, largely due to the delays experienced with the "Improved Virginia". These 20 submarines (10 Block V, 5 Block VI, 5 Block VII) would carry VPM bringing the total number of Virginia class submarines to 48 (including the 28 submarines in Blocks I, II, III and IV). The CBO in its 2012 report states that 33 Virginia class submarines will be procured in the 2013-2032 timeframe,[104] resulting in 49 submarines in total since 16 were already procured by the end of 2012.[100] Such a long production run seems unlikely but it should be noted that another naval program, the Arleigh Burke-class destroyer, is still ongoing even though the first vessel was procured in 1985.[105][106] However, other sources believe that production will end with Block V.[107] In addition, data provided in CBO reports tends to vary considerably compared to earlier editions.[6][108]

In 2013 execution of a 10 submarine contract was put in doubt by Budget sequestration in 2013.[109] On April 28, 2014, the Navy awarded a $17.6 billion order for two subs to be built during each of the next five years.[110]

Improved Virginia

Initially dubbed Future Attack Submarine.[111] Improved Virginia-class submarines will be an evolved version of the Virginia-class. It was planned that the first "Improved" Virginia-class submarine would be procured in 2025.[112] However, according to some reports their introduction has been pushed back by eight years, to 2033.[113]

See also

- 095-class submarine, the latest for China's People's Liberation Army Navy, first launched in 2010

- Astute-class submarine, the latest in service with the British Navy since 2010

- Barracuda-class submarine, the latest for the French Navy, with the first to be launched in 2016

- Yasen-class submarine, the latest for the Russian Navy, first launched in 2010

References

- ^ O'Rourke, Ronald (28 June 2013). "Navy Virginia (SSN-774) Class Attack Submarine Procurement: Background and Issues for Congress" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. p. 7. The USN's budget request for two Virginias in financial year 2014 (FY2014) is US$5,414.2 million, including $1,530.8m of advance funding from previous years.

- ^ Cowan, Simon (5 November 2012). "Facts favour nuclear-powered submarines". Retrieved 9 November 2012.

- ^ a b c "Construction Begins on SSN 787; Navy Transitions to Building Two Virginia Class Submarines Per Year". Retrieved 11 November 2011.

- ^ a b "US Navy 21st Century - SSN Virginia Class". Jeffhead.com. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- ^ a b "Submarine Industrial Base Council". Submarinesuppliers.org. 22 December 2008. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- ^ a b "An Analysis of the Navy's Fiscal Year 2013 Shipbuilding Plan" (PDF). Congressional Budget Office. July 2012. Retrieved 17 October 2012. Cite error: The named reference "cbo" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b "SSN-774 Virginia class". Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- ^ "Navy Report on New Attack Submarine (Senate - July 21, 1992)". Federation of American Scientists. Retrieved 15 December 2012.

- ^ Navy Considers Future After Virginia-Class Subs - Defensetech.org, 12 February 2014

- ^ a b c Baker, A. D. III (1998). Combat Fleets of the World, 1998–1999. USA. p. 1005. ISBN 1-55750-111-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b "Virginia Class". Navy.mil. Retrieved 6 February 2013.

- ^ "Newsroom". BAE Systems. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- ^ Hool, Jack; Nutter, Keith (2003). Damned Un-English Machines, a history of Barrow-built submarines. Tempus. p. 180. ISBN 0-7524-2781-4.

- ^ "SSN774 Virginia-class Fast Attack Submarine". Tech.military.com. Retrieved 30 September 2012.

- ^ "Special Purpose Sonar". Ultra Electronics Ocean Systems. Retrieved 15 December 2021.

- ^ Moreavek, Leonard, LTJG; Brudner, T.J (1999). "USS Asheville Leads the Way in High Frequency Sonar". Undersea Warfare Magazine. 1 (3). Retrieved 15 December 2012.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "GAO-09-326SP" (PDF). Government Accounting Office. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- ^ "PCU Virginia (SSN-774)". Navy.mil. 15 May 2000. Retrieved 6 February 2013.

- ^ "NSSN Virginia Class Attack Submarine". Naval Technology. 15 June 2011. Retrieved 6 February 2013.

- ^ "Raytheon News Release Archive". Raytheon.mediaroom.com. 30 January 2006. Retrieved 6 February 2013.

- ^ "General Dynamics To Upgrade Submarine Weapons Control Systems". Defense Industry Daily. 21 July 2009. Retrieved 12 November 2013.

- ^ "AN/BYG-1 Submarine Tactical Control System (TCS)". Gd-ais.com. Retrieved 6 February 2013.

- ^ "General Dynamics continues project to upgrade submarine electronics with COTS computers - Military & Aerospace Electronics". Militaryaerospace.com. 27 June 2013. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- ^ a b c "USS Virginia SSN-774-A New Steel Shark at Sea". Applied Technology Institute. Retrieved 15 December 2021.

- ^ a b "Submarine Industrial Base Council". Submarinesuppliers.org. 22 December 2008. Retrieved 6 February 2013.

- ^ "Naval Submarine League". Navalsubleague.com. 27 September 2012. Retrieved 6 February 2013.

- ^ Roberts, Jim (2011). "Double Vision: Planning to Increase Virginia-Class Production". Undersea Warfare. Retrieved 12 November 2013.

- ^ Admiral, Rear. "The Sweet Smell of Acquisition Success | U.S. Naval Institute". Usni.org. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- ^ "Statement of The Honorable Duncan Hunter, Chairman, Subcommittee on Military Procurement, Submarine Force Structure and Modernization". FAS Military Analysis Network. Federation of American Scientists. 27 June 2000. Retrieved 1 March 2008.

- ^ "Statement of Ronald O'Rourke Specialist in National Defense Congressional Research Service before the House Armed Services Committee Subcommittee on Projection Forces Hearing on Navy Force Architecture and Ship Construction" (PDF). 10 March 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2006. Retrieved 1 March 2008.

- ^ "AUV System Spec Sheet Cuttthroat LSV-2 configuration". Antonymous Undersea Vehicle Applications Center. Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- ^

Fox, David M., CDR, USN. "Small Subs Provide Big Payoffs for Submarine Stealth" (PDF). Antonymous Undersea Vehicle Applications Center. Retrieved 4 December 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "SSN-774 Virginia-class NSSN New Attack Submarine". Federation of American Scientists. 19 January 2009. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- ^ O'Rourke, Ronald (2 June 2004). "Navy Attack Submarine Force-Level Goal and Procurement Rate: Background and Issues for Congress" (PDF). Federation of American Scientists. Retrieved 1 March 2008.

- ^ http://insidedefense.com/secure/defense_docnum.asp?f=defense_2002.ask&docnum=NAVY-21-12-4 [dead link]

- ^ "Navy's Virginia Class Program Recognized for Acquisition Excellence". Navy.mil. 8 November 2008. Retrieved 21 April 2013.

- ^ "General Dynamics And Northrop Awarded Submarine Deal". The New York Times. 22 December 2008.[dead link]

- ^ McDermott, Jennifer (23 December 2010). "House, Senate ok defense bill for 2011; sub plan stays on track". The Day. Retrieved 17 October 2012.

- ^ Pike, John. "SSN-774 Virginia-class NSSN New Attack Submarine". GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved 30 September 2012.

- ^ Communication, Mass. "VARFD.aspx". Public.navy.mil. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- ^ This story was written by Naval Sea Systems Command Team Submarine Public Affairs. "Virginia Class Program Reaches Major Milestone". Navy.mil. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- ^ Hooper, Craig. "Virginia Class: When does hull coating separation endanger the boat?". Nextnavy.com. Retrieved 30 September 2012.

- ^ Hooper, Craig (7 November 2013). "The Virginia Peel: Why are $2 Billion Dollar Subs Losing Their Skin?". nextnavy.com. nextnavy.com. Retrieved 7 November 2013.

- ^ Mahnken, Tom (9 February 2011). "Growing concern down under". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- ^ Mar 04, 2013 @ 21:38 (2 March 2013). "U.S. Navy Sets Budget-cutting Plans in Motion". Blogs.defensenews.com. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "CRS RL32914" (PDF). Federation of American Scientists. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- ^ "Tango Bravo". Strategic Technology Office. DARPA. Retrieved 17 October 2012.

- ^ Freedberg Jr., Sydney J. (16 April 2014). "Navy Sub Program Stumbles: SSN North Dakota Delayed By Launch Tube Troubles". breakingdefense.com. Breaking Media, Inc. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- ^ Hasslinger, Karl; Pavlos, John (Winter 2012). "The Virginia Payload Module". www.public.navy.mil. United States Navy. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- ^ O'Rourke, Ronald (1 March 2012). "CRS-RL32418 Navy Virginia (SSN-774) Class Attack Submarine Procurement: Background and Issues for Congress". Congressional Research Service. OpenCRS. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- ^ Hasslinger, Karl; Pavlos, John (2012). "The Virginia Payload Module: A Revolutionary Concept for Attack Submarines". Undersea Warfare. Retrieved 12 November 2013.

- ^ "Navy Selects Virginia Payload Module Design Concept | USNI News". News.usni.org. 4 November 2013. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- ^ "Document: PEO Subs Overview of U.S. Navy Undersea Programs | USNI News". News.usni.org. 24 October 2013. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- ^ http://www.public.navy.mil/subfor/underseawarfaremagazine/issues/archives/issue_47/virginia_2.html

- ^ Grossman, Elaine M. "U.S. Senate Panel Curbs Navy Effort to Add Missiles to Attack Submarines | Global Security Newswire". NTI. Retrieved 6 February 2013.

- ^ "Navy cuts fleet goal to 306 ships". NavyTimes.com. 4 July 2010. Retrieved 6 February 2013.

- ^ Enter your Company or Top-Level Office. "OMA: Lower Ohio-Class Replacement Cost Tied To VA-Class Multiyear Deal: Could Achieve 8 To 15 Percent Savings". Ct.gov. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- ^ Kris Osborn (28 January 2014). "Navy, Electric Boat Test Tube-Launched Underwater Vehicle". Defense Tech. Retrieved 9 February 2014.

- ^ Greenert, Admiral Jonathan (18 September 2013). "Statement Before The House Armed Services Committee On Planning For Sequestration In FY 2014 And Perspectives Of The Military Services On The Strategic Choices And Management Review" (PDF). US House of Representatives. Retrieved 21 September 2013.

- ^ Grossman, Elaine M. (31 July 2013). "Pentagon, Lawmakers Deal Blows to Navy Fast-Strike Missile Effort". National Journal.

- ^ http://www.ewp.rpi.edu/hartford/~ernesto/F2010/EP2/Materials4Students/Misiaszek/NuclearMarinePropulsion.pdf

- ^ "U.S. Naval Reactors". Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- ^ Thomas, Doug (2008). "Submarine Developments: Air-Independent Propulsion" (PDF). Canadian Naval Review. Retrieved 15 December 2021.

- ^ Ted Kennedy; John Conyers (20 October 1994). "Lessons of Prior Programs May Reduce New Attack Submarine Cost Increases and Delays" (PDF). Government Accountability Office. Retrieved 12 November 2013.

- ^ "Virginia Class Sub Program Wins Acquisition Award". Defenseindustrydaily.com. 20 November 2008. Retrieved 23 March 2013.

- ^ "NSSN Virginia Class Attack Submarine – Naval Technology". Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- ^ "Acoustic Countermeasures". Ultra Electronics Ocean Systems. Retrieved 15 December 2021.

- ^ Patani, Arif (24 September 2012). "Next Generation Ohio-Class". Navylive.dodlive.mil. Retrieved 21 April 2013.

- ^ a b http://www.public.navy.mil/subfor/underseawarfaremagazine/Issues/Archives/issue_43/build_plan.html

- ^ "Microsoft Word - VA Class ASNE Paper FINAL_FIG-4-text change.doc" (PDF). Retrieved 21 April 2013.

- ^ "Navy Takes Delivery of New Submarine". Military.com. 22 February 2008. Retrieved 1 March 2008.

- ^ Butler, John. "The Sweet Smell of Acquisition Success | U.S. Naval Institute". Usni.org. Retrieved 21 April 2013.

- ^ O'Rourke, Ronald (27 September 2013). "Navy Virginia (SSN-774) Class Attack Submarine Procurement: Background and Issues for Congress" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. Retrieved 12 November 2013.

- ^ "Local News". Hartford Courant. Retrieved 21 June 2007.[dead link]

- ^ "Secretary of the Navy Sets New Mexico Commissioning Date". Navy League of the United States. 14 December 2009. Retrieved 4 January 2009.

- ^ "California To Be Commissioned".[dead link]

- ^ "USS Mississippi Joins the Navy". Sun Herald.[dead link]

- ^ "Submarine USS Minnesota to be commissioned Saturday". Pioneer Press. twincities.com. 26 October 2012. Retrieved 27 October 2012.

- ^ "Virginia Block III: The Revised Bow". Retrieved 20 May 2008.

- ^ "Submarine Technology thru the Years". Navy.mil. 19 July 1997. Retrieved 23 March 2013.

- ^ Paul Lambert. "Official USS Tullibee (SSN 597) Web Site - USS Tullibee History". Usstullibee.com. Retrieved 23 March 2013.

- ^ Admiral, Rear. "The Sweet Smell of Acquisition Success | U.S. Naval Institute". Usni.org. Retrieved 23 March 2013.

- ^ "Submarine Photo Index". Navsource.org. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ^ "Navy Delays Commissioning of Latest Nuclear Attack Submarine | USNI News". News.usni.org. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ^ "Navy Names Two Virginia Class Submarines". DefenseLink.mil. 15 July 2008. Retrieved 15 July 2008.

- ^ "Заложен киль одиннадцатой подводной лодки типа Virginia для ВМС США". Flotprom.ru. 14 May 2012. Retrieved 30 September 2012.

- ^ "Navy christens new attack submarine North Dakota". Times Union. 2 November 2013. Retrieved 12 November 2013.

- ^ "Navy Names Virginia Class Submarine USS John Warner Story Number: NNS090108-13". navy.mil. 8 January 2009. Retrieved 9 January 2009.

- ^ "Newport News Shipbuilding Celebrates Series of Firsts During Keel-Laying Ceremony for John Warner". Huntington Ingalls Industries. 16 March 2013.

- ^ "First Sailors Report to PCU Illinois". Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ^ "Navy's newest submarine to be named USS Washington". KOMO News. 13 April 2012. Retrieved 30 September 2012.

- ^ LaGrone, Sam (28 April 2014). "U.S. Navy Awards 'Largest Shipbuilding Contract' in Service History". usni.org. U.S. NAVAL INSTITUTE. Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- ^ "Contracts for Tuesday, April 17, 2012". Defense.gov. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- ^ "Contracts for Friday, December 28, 2012". Defense.gov. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- ^ "Press Release Detail". Generaldynamics.com. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- ^ a b "Funding For U.S. Navy Subs Runs Deep". Aviationweek.com. 10 April 2013. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- ^ "On Watch 2012 | Shipbuilding | Virginia Class". Navsea.navy.mil. Retrieved 6 February 2013.

- ^ "Virginia Payload Module (VPM)". Retrieved 4 July 2011.

- ^ "Naval Submarine League". Navalsubleague.com. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- ^ Labs, Eric (July 2012). "An Analysis of the Navy's Fiscal Year 2013 Shipbuilding Plan" (PDF). Congressional Budget Office. Retrieved 12 November 2013.

- ^ O'Rourke, Ronald (22 October 2013). "Navy DDG-51 and DDG-1000 Destroyer Programs: Background and Issues for Congress" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. Retrieved 12 November 2013.

- ^ Admiral, Vice. "Now Hear This - The Right Destroyer at the Right Time". Usni.org. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- ^ John Pike. "SSN-774 Virginia-class NSSN New Attack Submarine". Globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- ^ "An Analysis of the Navy's Shipbuilding Plans". Issuu.com. 10 March 2011. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- ^ Freedburg, Sydney (12 September 2013). "Navy To HASC: We're About To Sign Sub Deals We Can't Pay For". Breaking Defense. Retrieved 12 November 2013.

- ^ http://www.navytimes.com/article/20140428/NEWS04/304280038/Navy-orders-10-new-submarines-record-17-6B

- ^ "Federation of American Scientists :: Future Attack Submarine". Fas.org. 16 January 2013. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- ^ Labs, Eric J (9 March 2011). "An Analysis of the Navy's Shipbuilding Plans". Congressional Budget Office. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- ^ "An Analysis of the Navy's Fiscal Year 2013 Shipbuilding Plan" (PDF). Congressional Budget Office. July 2012. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

Further Reading

- Clancy, Tom. Submarine : a guided tour inside a nuclear warship. New York, N.Y. : Berkley Books, 2002. ISBN 0-425-18300-9 OCLC 48749330.

- Christley, Jim. US nuclear submarines : the fast attack. Oxford, UK, 2007. ISBN 1-846-03168-0 OCLC 141383046.

- Gresham, John and Westwell, Ian. Seapower. Edison, N.J. : Chartwell Books, 2004. ISBN 0-785-81792-1 OCLC 56578494.

- Polmar, Norman. The Naval Institute guide to the ships and aircraft of the U.S. fleet. Annapolis, Md. : Naval Institute Press, 2001. ISBN 1-557-50656-6 OCLC 47105698.

External links

- Holian, Thomas (2007). "Voices from Virginia". Undersea Warfare Magazine. 9 (2). Early Impressions from a First-in-Class

- Johnson, Dave, CAPT; Muniz, Dustin, LTJG (2007). "More for Less". Undersea Warfare. 9 (2).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)The Navy’s Plan to Reduce Costs on Virginia-class Submarines While Increasing Production - Little, Molly (Summer 2008). "The Elements of Virginia". Undersea Warfare Magazine (38). Updates on the boats of the Virginia-class

- Little, Molly (Summer 2008). "A Snapshot of the Virginia-class With Rear Adm. (sel.) Dave Johnson". Undersea Warfare (38). Q&A on the Virginia-class program since the Winter 2007 article

- Naval History & Heritage Command

- Virginia Class Submarines Some U.S. Navy Photos of Virginia Class Submarines

- NSSN Virginia Class Attack Submarine, United States of America