William Rehnquist: Difference between revisions

Jimmuldrow (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

|||

| Line 69: | Line 69: | ||

After becoming Chief Justice, Rehnquist continued to lead the Court toward a more limited view of Congressional power under the [[commerce clause]] of the U.S. Constitution. For example, he wrote for a 5-to-4 majority in ''[[United States v. Lopez]]'', {{ussc|514|549|1995}}, striking down a federal law as exceeding congressional power under the [[commerce clause]]. This decision was followed by ''[[United States v. Morrison]]'', {{ussc|529|598|2000}}, in which Rehnquist struck down the Violence Against Women Act of 1994 as regulating conduct that does not have a significant effect on interstate commerce. Rehnquist also led the way in allowing greater state assistance to [[religion|religious]] schools, writing for another 5-to-4 majority in ''[[Zelman v. Simmons-Harris]]'', {{ussc|536|639|2002}}, approving a [[school voucher]] program that aided church schools along with other private schools. |

After becoming Chief Justice, Rehnquist continued to lead the Court toward a more limited view of Congressional power under the [[commerce clause]] of the U.S. Constitution. For example, he wrote for a 5-to-4 majority in ''[[United States v. Lopez]]'', {{ussc|514|549|1995}}, striking down a federal law as exceeding congressional power under the [[commerce clause]]. This decision was followed by ''[[United States v. Morrison]]'', {{ussc|529|598|2000}}, in which Rehnquist struck down the Violence Against Women Act of 1994 as regulating conduct that does not have a significant effect on interstate commerce. Rehnquist also led the way in allowing greater state assistance to [[religion|religious]] schools, writing for another 5-to-4 majority in ''[[Zelman v. Simmons-Harris]]'', {{ussc|536|639|2002}}, approving a [[school voucher]] program that aided church schools along with other private schools. |

||

Rehnquist voted for ''[[City of Boerne v. Flores]]'' ([[1997]]), which dealt with congressional enforcement of the First Amendment, via [[Fourteenth_Amendment_to_the_United_States_Constitution#Power_of_enforcement|Section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment]], and held that Congress must sometimes defer to the Court regarding interpretation of that Amendment, including the Equal Protection Clause (congressional “conclusions are entitled to much deference….[but] Congress' discretion is not unlimited”). |

|||

In 1999, Rehnquist became the second Chief Justice (after [[Salmon P. Chase]]) to preside over a presidential [[impeachment]] trial, during the proceedings against President [[Bill Clinton]]. In 2000, Rehnquist wrote a concurring opinion in ''[[Bush v. Gore]],'' the case that effectively ended the [[U.S. presidential election, 2000#Florida election results|presidential election controversy in Florida]]. He concurred with six other justices in that case that a violation of the Equal Protection Clause had occurred. |

In 1999, Rehnquist became the second Chief Justice (after [[Salmon P. Chase]]) to preside over a presidential [[impeachment]] trial, during the proceedings against President [[Bill Clinton]]. In 2000, Rehnquist wrote a concurring opinion in ''[[Bush v. Gore]],'' the case that effectively ended the [[U.S. presidential election, 2000#Florida election results|presidential election controversy in Florida]]. He concurred with six other justices in that case that a violation of the Equal Protection Clause had occurred. |

||

However, in other cases, Rehnquist adopted a more limited interpretation of equal protection, in cases like ''[[Romer v. Evans]]'' involving gays, ''[[Kimel v. Florida Board of Regents]]'' involving the elderly, and ''[[Board of Trustees of the University of Alabama v. Garrett]]'' involving the disabled. ''Kimel'' and ''Garrett'' were based on the |

However, in other cases, Rehnquist adopted a more limited interpretation of equal protection, in cases like ''[[Romer v. Evans]]'' involving gays, ''[[Kimel v. Florida Board of Regents]]'' involving the elderly, and ''[[Board of Trustees of the University of Alabama v. Garrett]]'' involving the disabled. ''Kimel'' and ''Garrett'' were based on the sovereign immunity of states doctrine, which was reaffirmed and extended by the Rehnquist Court. The sovereign immunity doctrine made it difficult, although not impossible in theory, to apply the Equal Protection Clause to state governments. Also, the Court held that for types of discrimination based on age or disability, as opposed to "race or gender" (as O'Connor phrased it in an opinion Rehnquist concurred with), only a rationality test was required, as opposed to strict scrutiny. Whether such discrimination was rational did not need to be decided on an individual basis. If some elderly people are competent, for example, state governments could still discriminate against all elderly people. And Rehnquist held that state discrimination against all disabled people was rational because, even though Congressional studies showed that many were willing and able to work, states could save money by not meeting a "reasonable accommodation" requirement, even though the law allowed a hardship exception to this requirement. And in ''Romer v. Evans'', Rehnquist thought that majority rights were more important than equal protection of the laws for gay residents of Colorado. The Court's ''[[Alexander v. Sandoval]]'' decision did affect the way equal protection is applied based on race or national origin in that the Court decided against allowing evidence of disparate impact for title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The ''Cannon'' decision cited as a precedent applied only to intentional discrimination based on the five to four opinion that the disparate impact aspect of the case wasn't part of the holding because it was mentioned in a footnote of the majority opinion. ''Cannon'' held in favor of allowing disparate impact tests in point of fact. |

||

Rehnquist voted for ''[[City of Boerne v. Flores]]'' ([[1997]]), and referred to it as a precedent for requiring Congress to defer to the Court for interpreting the Equal Protection Clause in a number of cases. ''Boerne'' held that any statute that Congress enacted to enforce the provisions of the Equal Protection Clause had to be "congruent and proportional" to the wrong it sought to correct. The Rehnquist Court’s congruence and proportionality theory replaced the ratchet theory advanced in ''[[Katzenbach v. Morgan]]'' ([[1966]]). The ratchet theory held that Congress could ratchet up civil rights beyond what the Court had recognized, but that Congress could not ratchet down judicially recognized rights. The Rehnquist Court's congruence and proportionality theory made it easier to revive older precedents for preventing Congress from going too far in enforcing equal protection of the laws. ''Katzenbach v. Morgan'' was mentioned in the ''Garrett'' dissent written by Justice Breyer, with whom Justice Stevens, Justice Souter and Justice Ginsburg join, dissenting. |

|||

Chief Justice Rehnquist was a reliable foe of the Court's 1973 ''[[Roe v. Wade]]'' decision. In 1992, that decision survived by a 5-4 vote, in ''[[Planned Parenthood v. Casey]]'' which relied heavily on the doctrine of [[stare decisis]]. Dissenting in ''Casey'', Rehnquist criticized the Court's "newly minted variation on stare decisis," and asserted his belief "that ''Roe'' was wrongly decided, and that it can and should be overruled consistently with our traditional approach to stare decisis in constitutional cases." |

Chief Justice Rehnquist was a reliable foe of the Court's 1973 ''[[Roe v. Wade]]'' decision. In 1992, that decision survived by a 5-4 vote, in ''[[Planned Parenthood v. Casey]]'' which relied heavily on the doctrine of [[stare decisis]]. Dissenting in ''Casey'', Rehnquist criticized the Court's "newly minted variation on stare decisis," and asserted his belief "that ''Roe'' was wrongly decided, and that it can and should be overruled consistently with our traditional approach to stare decisis in constitutional cases." |

||

Revision as of 16:53, 26 December 2006

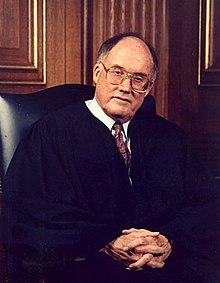

William Hubbs Rehnquist | |

|---|---|

| |

| 16th | |

| Nominated by | Ronald Reagan |

| Preceded by | Warren E. Burger |

| Succeeded by | John Roberts |

| 100th | |

| Nominated by | Richard Nixon |

| Preceded by | John Marshall Harlan II |

| Succeeded by | Antonin Scalia |

William Hubbs Rehnquist (October 1, 1924 – September 3, 2005) was an American lawyer, jurist, and a political figure, who served as an Associate Justice on the Supreme Court of the United States and later as the Chief Justice of the United States. A proponent of a federalism that favored state power, his legacy includes the first limits on Congress's power under the Commerce Clause of the United States Constitution since the 1930s.

Early life

Rehnquist was born in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, as William Donald Rehnquist [1] and grew up in the suburb of Shorewood. His father, William Benjamin Rehnquist, was a paper salesman; his mother, Margery Peck Rehnquist, was a translator and homemaker. Rehnquist changed his middle name to Hubbs, his grandmother's maiden name, during his high school years.

After graduating from Shorewood High School in 1942, Rehnquist attended Kenyon College, in Gambier Ohio, for one quarter in the fall of 1942, before entering the U.S. Army Air Forces. Rehnquist served in World War II from March, 1943 to 1946. He was put into a pre-meteorology program and was assigned to Denison University until February, 1944, when the program was shut down. He served three months at Will Rogers Field in Oklahoma City, three months in Carlsbad, New Mexico, and then went to Hondo, Texas for a few months. He was then chosen for another training program which began at Chanute Field, Illinois, and ended at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey. The program was designed to teach the maintenance and repair of weather instruments. In the summer of 1945, he went overseas and served as a weather observer in North Africa.

After the war ended, Rehnquist attended Stanford University with assistance under the provisions of the G.I. Bill. In 1948, he received a bachelor's degree and a master's degree in political science. In 1950, he went to Harvard University, where he received a master's degree in government. He returned later to the Stanford Law School, where he graduated in the same class as Sandra Day O'Connor, who would later serve alongside him on the Supreme Court. Sandra Day and Rehnquist briefly dated at Stanford.[2] It has been said that Rehnquist graduated first in his class, probably based on the fact that he was class valedictorian during graduation ceremonies, but Stanford's official position is that the law school did not rank students in 1952. [3]

Rehnquist went to Washington, D.C. to work as a law clerk for Justice Robert H. Jackson during the court's 1951-1952 terms. There, he wrote a memorandum arguing against federal-court-ordered school desegregation while the court was considering the landmark Brown v. Board of Education case. Rehnquist’s memo, entitled “A Random Thought on the Segregation Cases,” defended the separate-but-equal doctrine. In that memo, Rehnquist said:

- I realize that it is an unpopular and unhumanitarian position, for which I have been excoriated by 'liberal' colleagues but I think Plessy v. Ferguson was right and should be reaffirmed....To the argument ... that a majority may not deprive a minority of its constitutional right, the answer must be made that while this is sound in theory, in the long run it is the majority who will determine what the constitutional rights of the minority are.[4][5]

During his 1971 confirmation hearings, Rehnquist said, "I believe that the memorandum was prepared by me as a statement of Justice Jackson's tentative views for his own use." According to liberal law professor Mark Tushnet, Justice Jackson’s longtime legal secretary called Rehnquist’s Senate testimony an attempt to “smear[] the reputation of a great justice,”[6] but there is considerable evidence that Justice Jackson only voted for Brown after changing his mind.[7] Later at his 1986 hearings for the slot of Chief Justice, Rehnquist tried to put further distance between himself and the 1952 memo: "The bald statement that Plessy was right and should be reaffirmed, was not an accurate reflection of my own views at the time."[8] However, Rehnquist acknowledged defending Plessy in arguments with fellow law clerks.[9] In any event, while later serving on the Supreme Court, Rehnquist made no effort to reverse or undermine the Brown decision, and frequently relied upon it as precedent,[10] although his opinions interpreted the Equal Protection Clause more narrowly than some of his colleagues regarding the disabled, the elderly, gays, and other classifications not based on race or national origin.

Regarding Terry v. Adams,[11] which was about the right of African-Americans to vote in an allegedly private Texas election, Rehnquist wrote the following in a memorandum to Justice Jackson:

- The Constitution does not prevent the majority from banding together, nor does it attaint success in the effort. It is about time the Court faced the fact that the white people of the south don’t like the colored people: the constitution restrains them from effecting this dislike through state action but it most assuredly did not appoint the Court as a sociological watchdog to rear up every time private discrimination raises its admittedly ugly head.[12]

In another memorandum to Justice Jackson regarding the same case (Terry), Rehnquist wrote:

- [C]lerks began screaming as soon as they saw this that "Now we can show those damn southerners, etc"....I take a dim view of this pathological search for discrimination...and as a result I now have something of a mental block against the case.[13]

Rehnquist moved to Phoenix, Arizona, where he was in private law practice from 1953 to 1969. During these years, he was active in the Republican Party and served as a legal advisor to Barry Goldwater's 1964 presidential campaign. Many years later, during the 1986 Senate hearings on his chief justice nomination, several people came forward to complain about what they viewed as Rehnquist's attempts to discourage minority voters in Arizona elections when Rehnquist served as a "poll watcher" in the early 1960s. Rehnquist denied the charges, and "Vincent Maggiore, then chairman of the Phoenix-area Democratic Party, said he had never heard any negative reports about Rehnquist's Election Day activities. 'All of these things,' he said, 'would have come through me.'"[14]

Justice Department

When President Richard Nixon was elected in 1968, Rehnquist returned to work in Washington. He served as Assistant Attorney General of the Office of Legal Counsel, from 1969 to 1971. In this role, he served as the chief lawyer to Attorney General John Mitchell. President Nixon mistakenly referred to him as "Renchburg" in several of the tapes of Oval Office conversations revealed during the Watergate investigations. Because he was well-placed in the Justice Department, Rehnquist was mentioned for many years as a possibility for the source known as Deep Throat during the Watergate scandal. (Once Bob Woodward revealed on May 31, 2005, that W. Mark Felt was Deep Throat, this speculation ended, of course.)

Associate Justice

Nixon nominated Rehnquist to replace John Marshall Harlan II on the Supreme Court upon Harlan's retirement, and after being confirmed by the Senate by a 68–26 vote on December 10, 1971, Rehnquist took his seat as an Associate Justice on January 7, 1972. There were two vacancies on the court at the time; Nixon nominated Lewis Franklin Powell, Jr. to fill the other.

On the Burger Court, Rehnquist promptly established himself as the most conservative of Nixon's appointees, taking a narrow view of the Fourteenth Amendment and a broad view of state power. He voted against the expansion of school desegregation plans and the establishment of legalized abortions, dissenting in Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973), and in favor of school prayer, capital punishment and states' rights. Reluctant to compromise, Rehnquist was the most frequent sole dissenter during the Burger years. He actively sought to promote his conservative agenda within the Court, especially in the area of federalism, and voted most often alongside the also conservative Chief Justice.

He expressed his views about the Equal Protection Clause in cases like Trimble v. Gordon:[15]

"Unfortunately, more than a century of decisions under this Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment have produced .... a syndrome wherein this Court seems to regard the Equal Protection Clause as a cat-o'-nine-tails to be kept in the judicial closet as a threat to legislatures which may, in the view of the judiciary, get out of hand and pass 'arbitrary,' 'illogical,' or 'unreasonable' laws. Except in the area of the law in which the Framers obviously meant it to apply - classifications based on race or on national origin, the first cousin of race - the Court's decisions can fairly be described as an endless tinkering with legislative judgments, a series of conclusions unsupported by any central guiding principle."

Yet, nineteen years later, Rehnquist would agree to strike down the male-only admissions policy of the Virginia Military Institute, as violative of this Clause.[16] Rehnquist remained skeptical about the Court's Equal Protection Clause jurisprudence; some of his opinions most favorable to equality resulted from statutory rather than constitutional interpretation. For example, in Meritor Savings Bank v. Vinson, Rehnquist established a hostile-environment sexual harassment cause of action under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, including protection against psychological aspects of harassment in the workplace.

Rehnquist wrote the decision Diamond v. Diehr, 450 U.S. 175 (1981), which punched a hole in the dike against software patents in the United States erected by Justice Stevens in Parker v. Flook, 437 U.S. 584 (1978); the dike collapsed within a few years and software patenting is now virtually unlimited. In Sony Corp. of America v. Universal City Studios, Inc., pertaining to video cassette recorders such as the Betamax system, Justice Stevens again wrote an opinion providing a broad fair use doctrine while Rehnquist joined the dissent, which supported stronger copyrights. Years later, in Eldred v. Ashcroft, 537 U.S. 186 (2003), Rehnquist was in the majority favoring the copyright holders, with Justice Stevens dissenting in favor of a narrower construction of copyright law.

Chief Justice

When Chief Justice Warren Burger retired in 1986, President Ronald Reagan nominated Rehnquist to fill the position. During confirmation hearings, Senator Edward Kennedy challenged Rehnquist on his unwitting ownership of property that had a restrictive covenant against sale to Jews; such covenants are unenforceable under Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948).[17] Despite this and other controversies, the Senate confirmed his appointment by a 65-33 vote, and he assumed the office on September 26. Rehnquist's seat as an associate justice was filled by Antonin Scalia.

After becoming Chief Justice, Rehnquist continued to lead the Court toward a more limited view of Congressional power under the commerce clause of the U.S. Constitution. For example, he wrote for a 5-to-4 majority in United States v. Lopez, 514 U.S. 549 (1995), striking down a federal law as exceeding congressional power under the commerce clause. This decision was followed by United States v. Morrison, 529 U.S. 598 (2000), in which Rehnquist struck down the Violence Against Women Act of 1994 as regulating conduct that does not have a significant effect on interstate commerce. Rehnquist also led the way in allowing greater state assistance to religious schools, writing for another 5-to-4 majority in Zelman v. Simmons-Harris, 536 U.S. 639 (2002), approving a school voucher program that aided church schools along with other private schools.

In 1999, Rehnquist became the second Chief Justice (after Salmon P. Chase) to preside over a presidential impeachment trial, during the proceedings against President Bill Clinton. In 2000, Rehnquist wrote a concurring opinion in Bush v. Gore, the case that effectively ended the presidential election controversy in Florida. He concurred with six other justices in that case that a violation of the Equal Protection Clause had occurred.

However, in other cases, Rehnquist adopted a more limited interpretation of equal protection, in cases like Romer v. Evans involving gays, Kimel v. Florida Board of Regents involving the elderly, and Board of Trustees of the University of Alabama v. Garrett involving the disabled. Kimel and Garrett were based on the sovereign immunity of states doctrine, which was reaffirmed and extended by the Rehnquist Court. The sovereign immunity doctrine made it difficult, although not impossible in theory, to apply the Equal Protection Clause to state governments. Also, the Court held that for types of discrimination based on age or disability, as opposed to "race or gender" (as O'Connor phrased it in an opinion Rehnquist concurred with), only a rationality test was required, as opposed to strict scrutiny. Whether such discrimination was rational did not need to be decided on an individual basis. If some elderly people are competent, for example, state governments could still discriminate against all elderly people. And Rehnquist held that state discrimination against all disabled people was rational because, even though Congressional studies showed that many were willing and able to work, states could save money by not meeting a "reasonable accommodation" requirement, even though the law allowed a hardship exception to this requirement. And in Romer v. Evans, Rehnquist thought that majority rights were more important than equal protection of the laws for gay residents of Colorado. The Court's Alexander v. Sandoval decision did affect the way equal protection is applied based on race or national origin in that the Court decided against allowing evidence of disparate impact for title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The Cannon decision cited as a precedent applied only to intentional discrimination based on the five to four opinion that the disparate impact aspect of the case wasn't part of the holding because it was mentioned in a footnote of the majority opinion. Cannon held in favor of allowing disparate impact tests in point of fact.

Rehnquist voted for City of Boerne v. Flores (1997), and referred to it as a precedent for requiring Congress to defer to the Court for interpreting the Equal Protection Clause in a number of cases. Boerne held that any statute that Congress enacted to enforce the provisions of the Equal Protection Clause had to be "congruent and proportional" to the wrong it sought to correct. The Rehnquist Court’s congruence and proportionality theory replaced the ratchet theory advanced in Katzenbach v. Morgan (1966). The ratchet theory held that Congress could ratchet up civil rights beyond what the Court had recognized, but that Congress could not ratchet down judicially recognized rights. The Rehnquist Court's congruence and proportionality theory made it easier to revive older precedents for preventing Congress from going too far in enforcing equal protection of the laws. Katzenbach v. Morgan was mentioned in the Garrett dissent written by Justice Breyer, with whom Justice Stevens, Justice Souter and Justice Ginsburg join, dissenting.

Chief Justice Rehnquist was a reliable foe of the Court's 1973 Roe v. Wade decision. In 1992, that decision survived by a 5-4 vote, in Planned Parenthood v. Casey which relied heavily on the doctrine of stare decisis. Dissenting in Casey, Rehnquist criticized the Court's "newly minted variation on stare decisis," and asserted his belief "that Roe was wrongly decided, and that it can and should be overruled consistently with our traditional approach to stare decisis in constitutional cases."

Rehnquist was not reluctant to apply stare decisis when he believed appropriate. For example, in Dickerson v. United States, Rehnquist voted to reaffirm the Court's famous decision in Miranda v. Arizona based not only on the notion of adhering to precedent, but also based on his belief that "the totality-of-the-circumstances test ... is more difficult than Miranda for law enforcement officers to conform to, and for courts to apply in a consistent manner."

Shortly after Dickerson was decided, the Court dealt with another abortion case, this time dealing with so-called partial birth abortion in Stenberg v. Carhart. Again, a 5-4 decision, and again a dissent from Rehnquist urged that stare decisis should not be the sole consideration: "I did not join the joint opinion in Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pa. v. Casey, 505 U. S. 833 (1992), and continue to believe that case is wrongly decided."

In his capacity as Chief Justice, Rehnquist administered the Oath of Office to Presidents Bush, Clinton and George W. Bush.

Declining health and death

On October 26, 2004, the Supreme Court press office announced that Rehnquist had recently been diagnosed with thyroid cancer. After several months out of the public eye, Rehnquist administered the oath of office to President George W. Bush at his second inauguration on January 20, 2005, despite doubts over whether his health would permit his participation. He arrived using a cane, walked very slowly, and left immediately after the oath itself was administered.

After missing 44 oral arguments before the Court in late 2004 and early 2005, Rehnquist appeared on the bench again on March 21, 2005. During his absence, however, he remained involved in the business of the Court, participating in many of the decisions and deliberations.

On July 1, 2005, Rehnquist's colleague Sandra Day O'Connor announced her retirement from her position of Associate Justice, after consulting with Rehnquist and learning that he intended to remain on the Court. Commenting on the frenzy of speculation over his retirement, Rehnquist joked with a reporter who asked if he would be retiring, "That's for me to know and you to find out."[18]

Rehnquist died at his Arlington, Virginia, home on September 3, 2005, exactly four weeks short of his 81st birthday. Rehnquist was the first member of the Supreme Court to die in office since Justice Robert H. Jackson in 1954, and the first Chief Justice to die in office since Fred M. Vinson, in 1953.

On September 6, 2005, eight of Rehnquist's former law clerks, including Judge John Roberts, his eventual successor, served as his pallbearers as his casket was placed on the same catafalque that bore Abraham Lincoln's casket as he lay in state in 1865. [19] Rehnquist's body remained in the Great Hall of the Supreme Court until his funeral on September 7, 2005, a Lutheran service conducted at the Roman Catholic Cathedral of St. Matthew the Apostle in Washington, D.C. The presiding minister was George Evans, the former chief of Chaplains for the US Navy. Rehnquist was eulogized by President George W. Bush and Justice Sandra Day O'Connor, as well as by members of his family. [20] His funeral was followed by a private burial service, in which he was interred next to his late wife, Nan, at Arlington National Cemetery [21].

Succession as Chief Justice

Rehnquist's death, just over two months after O'Connor announced her retirement, left two vacancies to be filled by President George W. Bush. On September 5, 2005, Bush withdrew the nomination of Judge John Roberts of the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals to replace O'Connor as Associate Justice, and instead nominated him to replace Rehnquist as Chief Justice. Roberts was confirmed by the U.S. Senate and sworn in as the new Chief Justice on September 29, 2005. Roberts had clerked for Rehnquist in 1980-1981.

Family life

- Rehnquist's paternal grandparents immigrated separately (although they may have known one another before) from Sweden in 1880. His grandfather Olof Andersson, who changed his surname from the patronymic Andersson to the family name Rehnquist, was born in the province of Värmland and his grandmother was born Adolfina Ternberg in Vretakloster (parish) in Östergötland. Rehnquist is one of two Chief Justices of Swedish descent, the other being Earl Warren, who had Norwegian-Swedish ancestry.

- Rehnquist’s maternal lineage traces back via New York to the Pilgrims and other early New England settlers.

- Rehnquist married Natalie "Nan" Cornell on August 29, 1953. She died on October 17, 1991, after suffering from ovarian cancer. The couple had three children: James, Janet and Nancy. Janet Rehnquist is a former Inspector General of the Department of Health and Human Services.

Trivia

- Rehnquist was a longtime cigarette smoker.

- Rehnquist added four gold stripes to each sleeve of his robe in 1995, after viewing a production of Gilbert and Sullivan's Iolanthe and being inspired by the costume of the Lord Chancellor. Rehnquist performed in Gilbert and Sullivan's Patience with the Washington Savoyards in 1986 (appropriately, as "the Solicitor").[22] In her remarks at his funeral, Associate Justice Sandra Day O'Connor said he told her the four gold stripes were "one for every five years" he had been a justice, but he never added more. The stripes also resemble the rank insignia for a Navy captain, so they could also have represented Rehnquist being in charge of the Supreme Court. His successor, Chief Justice John Roberts, chose not to continue the practice.

- Rehnquist was born the same day as former President Jimmy Carter.

- Rehnquist presided as Chief Justice for 19 years, making him the fourth-longest-serving Chief Justice after Melville Fuller, Roger Taney and John Marshall, and the longest-serving Chief Justice who had previously served as an Associate Justice.

- Rehnquist was a member of the Lutheran Church

- The last 11 years of Rehnquist's term as Chief Justice (1994-2005) marked the second longest tenure of one makeup of the Supreme Court; from August 3, 1994, when Justice Breyer joined the Court until September 3, 2005, when Rehnquist died the makeup of the Court was stable for 4049 days. This is second only to the period from February 3, 1812, when Joseph Story joined the Court until March 18, 1823, when Henry Brockholst Livingston died, which produced a stable Court for 4061 days.

- Rehnquist was 6 ft 2 in tall.

- Had a bobblehead doll created for him by the law journal The Green Bag.

- In October 2006, Middlebury College received an anonymous multi-million dollar donation for the creation of a William H. Rehnquist Professorship in the college's history department. The donation was enthusiastically received and announced at a lecture given by Rehnquist's successor John Roberts. The college's decision to accept the money and create the position was protested by students who felt misrepresented by Rehnquist's staunch conservative record.

- Late in his career, when asked by a reporter whether there was truth to the speculation that he would be retiring from the Court, Rehnquist responded, "That's for me to know and you to find out." [23]

Bibliography

- Thomas R. Hensley. The Rehnquist Court Justices, Rulings, and Legacy (2006) Print 1-57607-200-2; eBook 1-57607-560-5

- David L. Hudson. The Rehnquist Court: Understanding Its Impact and Legacy (2006)

- Herman Schwartz. The Rehnquist Court: Judicial Activism on the Right (2003)

- Mark Tushnet. A Court Divided: The Rehnquist Court and the Future of Constitutional Law (2005)

Books written by Rehnquist

- William H. Rehnquist (2004). The Centennial Crisis: The Disputed Election of 1876. Knopf Publishing Group. ISBN 0-375-41387-1.

- William H. Rehnquist (1998). All the Laws but One : Civil Liberties in Wartime. William Morrow & Co. ISBN 0-688-05142-1.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - William H. Rehnquist (1992). Grand Inquests: The Historic Impeachments of Justice Samuel Chase and President Andrew Johnson. Knopf Publishing Group. ISBN 0-679-44661-3.

- William H. Rehnquist (1987). The Supreme Court: How It Was, How It Is. William Morrow & Co. ISBN 0-688-05714-4.

- Revised edition: William H. Rehnquist (2001). The Supreme Court: A new edition of the Chief Justice's classic history. Knopf Publishing Group. ISBN 0-375-40943-2.

Notes

- ^ Greenhouse, Linda. Becoming Justice Blackmun. 235-236. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2005.

- ^ Biskupic, Joan. Sandra Day O'Connor: How the First Woman on the Supreme Court became its most influential justice. New York: Harper Collins, 2005

- ^ Debbie Kornmiller, O'Connor's class rank an error that won't die, Arizona Daily Star (July 10, 2005).

- ^ Commentary: From Law Clerk to Chief Justice, He Has Slighted Rights, Rehnquist's 1952 memo sheds light on today's court, Cass R. Sunstein, Los Angeles Times, May 17, 2004

- ^ Memos may not hold Roberts's opinions, The Boston Globe, Peter S. Canellos, August 23, 2005

- ^ Dershowitz, Professor of Law at Harvard, Mon Sep 5, 2005

- ^ See Michael Klarman, From Jim Crow to Civil Rights, pp. 300-301 (2004). Klarman writes that both Justices Douglas and Frankfurter wrote separate memoranda the week Brown was decided in 1954, stating that Justice Jackson would have dissented had the case been decided soon after the original conference in 1952.

- ^ Adam Liptak, The Memo That Rehnquist Wrote and Had to Disown, NY Times (September 11, 2005)

- ^ Memos may not hold Roberts's opinions, The Boston Globe, Peter S. Canellos, August 23, 2005 Here is what Rehnquist said in 1986 about his conversations with other clerks about Plessy:

S. Hrg. 99-1067, Hearings Before the Senate Committee on the Judiciary on the Nomination of Justice William Hubbs Rehnquist to beI thought Plessy had been wrongly decided at the time, that it was not a good interpretation of the equal protection clause to say that when you segregate people by race, there is no denial of equal protection. But Plessy had been on the books for 60 years; Congress had never acted, and the same Congress that had promulgated the 14th Amendment had required segregation in the District schools....I saw factors on both sides....I did not agree then, and I certainly do not agree now, with the statement that Plessy against Ferguson is right and should be reaffirmed. I had ideas on both sides, and I do not think I ever really finally settled in my own mind on that .... [A]round the lunch table I am sure I defended it....I thought there were good arguments to be made in support of it.

Chief Justice of the United States (July 29, 30, 31, and August 1, 1986).

- ^ Cases where Justice Rehnquist has cited Brown v. Board of Education in support of a proposition, S. Hrg. 99-1067, Hearings Before the Senate Committee on the Judiciary on the Nomination of Justice William Hubbs Rehnquist to be Chief Justice of the United States (July 29, 30, 31, and August 1, 1986). Also see Jeffery Rosen, Rehnquist the Great?, Atlantic Monthly (April 2005) ("Rehnquist ultimately embraced the Warren Court's Brown decision, and after he joined the Court he made no attempt to dismantle the civil-rights revolution, as political opponents feared he would").

- ^ Terry v. Adams, 345 U.S. 461 (1953)

- ^ Charles Lane, Head of the Class, Stanford Magazine (July/August 2005)

- ^ Tinsley E. Yarbrough, The Rehnquist Court and the Constitution, pages 2-3 (2000).

- ^ Amy Wilentz, Through the Wringer, Time Magazine (Aug. 11, 1986).

- ^ Trimble v. Gordon, 430 U.S. 762 (1977)

- ^ United States v. Virginia, 518 U.S. 515 (1996)

- ^ Alan S. Oser, Unenforceable Covenants are in Many Deeds, NY Times (August 1, 1986):

Mr. Rehnquist has said he was unaware of discriminatory restrictions on properties he bought in Arizona and Vermont, and officials in those states said today that he had never even been required to sign the deeds that contained the restrictions....He told the committee he would act quickly to get rid of the covenants. The restriction on the Vermont property prohibits the lease or sale of the property to "members of the Hebrew race"....The discriminatory language appears on the first page of the single-spaced document in the middle of a long paragraph filled with unrelated language regarding sewers and the construction of a mailbox.

- ^ D.C. Wonders When Rehnquist Will Go. FOXNews.com, July 10, 2005.

- ^ http://www.nytimes.com/2005/09/06/politics/16cnd-roberts.html

- ^ http://www.sfexaminer.com/articles/2005/09/07/ap/headlines/d8cfke7o0.txt

- ^ http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2005/09/04/AR2005090401066.html

- ^ Time magazine article on Rehnquist's performance with the Washington Savoyards.

- ^ http://www.foxnews.com/story/0,2933,161959,00.html

External links

See also

- 1971 Senate confirmation hearing

- 1986 Senate confirmation hearing

- United States Supreme Court cases during the Rehnquist Court

- Supreme court official bio (PDF)

- John Q. Barrett, William H. Rehnquist, Jackson law clerk

- 1969 memo on FOIA policy.

- Remarks of the Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist, Swedish Colonial Society's annual luncheon league, Philadelphia, April 9, 2001

- Remarks by the Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist to the American Meteorological Society, October 23, 2001

- CSPAN article explaining the four gold stripes

- [1]

Opinions

- Supreme Court Justice Rehnquist's Key Decisions - The Washington Post

- Legacy of William H. Rehnquist - Majority and Dissenting Opinions in Major Supreme Court Cases

Death

- Lane, Charles. "Chief Justice Dies at Age 80." The Washington Post, September 4, 2005. p. A01.

- Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist Dies - The Washington Post

- Emotion Overcomes Court at Goodbye to 'the Chief' The Washington Post

- The Rehnquist Legacy: 33 Years Turning Back the Court - The Washington Post

- In Rehnquist's Footsteps by Bruce Shapiro The Nation

- Tributes from fellow Supreme Court justices

- Supreme Court Chief Justice Rehnquist Dies - The New York Times

- Chief Justice Rehnquist Dies at 80 - The New York Times

- William H. Rehnquist Dies at 80; Led Conservative Revolution on Supreme Court - The New York Times

- The Legacy of Supreme Court Justice William Rehnquist - The New York Times

- Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist Dead - Fox News

- Chief Justice Rehnquist has died - CNN

- Supreme Court Press Release RE: Funeral Arrangements

- Obituaries by Jan Crawford Greenburg and The Economist

Template:Start U.S. Supreme Court composition Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition court lifespan Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1972-1975 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1975-1981 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1981-1986 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition CJ Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition court lifespan Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1986-1987 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1988-1990 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1990-1991 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1991-1993 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1993-1994 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1994-2005 Template:End U.S. Supreme Court composition

- Chief Justices of the United States

- Assistant Attorneys General of the United States

- American legal writers

- American political writers

- American historians

- American conservatives

- American World War II veterans

- American Lutherans

- Harvard University alumni

- Kenyon College alumni

- Stanford University alumni

- Denison University alumni

- Swedish-Americans

- People from Milwaukee

- People from Phoenix, Arizona

- Burials at Arlington National Cemetery

- 1924 births

- 2005 deaths