Frank Sturgis: Difference between revisions

Will Beback (talk | contribs) rm exceptional claim sourced to one-person website |

Undid revision 148827673 by Will Beback (talk)changed link source to Rolling Stone magazine not one person website |

||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

According to the 1975 [[Rockefeller Commission]] report, [[E. Howard Hunt|Hunt]] testified that he had never met Sturgis before they were introduced by [[Bernard Barker]] in Miami in 1972. Sturgis testified to the same effect, except that he did not recall whether the introduction had taken place in late 1971 or early 1972. Sturgis further testified that while he had often heard of "Eduardo," a CIA political officer who had been active in the work of the Cuban Revolutionary Council in Miami prior to the Bay of Pigs operation in April 1961, he had never met him and did not know until 1971 or 1972 that "Eduardo" was E. Howard Hunt.<ref>[http://www.aarclibrary.org/publib/church/rockcomm/html/Rockefeller_0132a.htm ''Report to the President by the Commission on CIA Activities Within the United States''] Chapter 19</ref> |

According to the 1975 [[Rockefeller Commission]] report, [[E. Howard Hunt|Hunt]] testified that he had never met Sturgis before they were introduced by [[Bernard Barker]] in Miami in 1972. Sturgis testified to the same effect, except that he did not recall whether the introduction had taken place in late 1971 or early 1972. Sturgis further testified that while he had often heard of "Eduardo," a CIA political officer who had been active in the work of the Cuban Revolutionary Council in Miami prior to the Bay of Pigs operation in April 1961, he had never met him and did not know until 1971 or 1972 that "Eduardo" was E. Howard Hunt.<ref>[http://www.aarclibrary.org/publib/church/rockcomm/html/Rockefeller_0132a.htm ''Report to the President by the Commission on CIA Activities Within the United States''] Chapter 19</ref> |

||

In a deathbed statement [http://www.rollingstone.com/politics/story/13893143/the_last_confessions_of_e_howard_hunt] released in 2007, [[Howard Hunt]] names Sturgis as one of the participants in the JFK assassination. |

|||

== Watergate burglary == |

== Watergate burglary == |

||

Revision as of 15:38, 4 August 2007

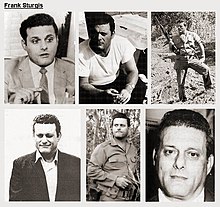

Frank Anthony Sturgis (December 9, 1924 – December 4, 1993), born Frank Angelo Fiorini, was one of the Watergate burglars. He served in Fidel Castro's revolutionary army as a soldier of fortune[citation needed], and later trained Cuban exiles for the Bay of Pigs Invasion.

Frank Fiorini Sturgis' family moved to Philadelphia when he was a child. In 1942, Sturgis joined the U.S. Marine Corps and, during the Second World War, served in the Pacific.

After the war Sturgis attended the Virginia Polytechnic Institute before becoming the manager of the Whitehorse Tavern. He also served in the U.S. Army (1950-52). This was followed by a spell as the owner-manager of Tophat Nightclub in Virginia Beach. His family owned a fruit stand in the area, while in Norfolk Sturgis attended a few classes at Old Dominion University.

Entry into intelligence operations

On September 23, 1952, Frank Fiorini filed a petition in the Circuit Court of the City of Norfolk, Virginia, to change his name to Frank Anthony Sturgis, adopting the surname of his stepfather Ralph Sturgis, whom his mother had married in 1937. Whether coincidentally or not, the new name resembled that of Hank Sturgis, the fictional hero of E. Howard Hunt's 1949 novel, Bimini Run, whose life parallels Frank Sturgis' life from 1942 to 1949 in certain salient respects.[1]

In 1956, Sturgis moved to Cuba. He also spent time in Mexico, Venezuela, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Panama, and Honduras. It is believed that during this time Sturgis worked as either a soldier of fortune or a contract agent for the Central Intelligence Agency, or both. The 1975 Rockefeller Commission report, however, found that "Frank Sturgis was not an employee or agent of the CIA either in 1963 or at any other time."[2]

Sturgis also became involved in gunrunning to Cuba. On July 30, 1958, Sturgis was arrested for illegal possession of arms, but was released without charge. There is some evidence that, in 1959, Sturgis had contact with Lewis McWillie, the manager of the Tropicana Casino.

After Fidel Castro gained control of Cuba, Sturgis formed the Anti-Communist Brigade. In his book Counter-Revolutionary Agent, Hans Tanner claims that the organization was "being financed by dispossessed hotel and gambling owners" who operated freely under Fulgencio Batista.

In 1959, Sturgis became involved with Marita Lorenz, who was having an affair with Fidel Castro. In January 1960, Sturgis and Lorenz took part in a failed attempt to poison Castro. It is also believed that Sturgis was involved in helping the CIA organize the Bay of Pigs invasion.

Sturgis was also a member of Operation 40. He later explained: "this assassination group (Operation 40) would upon orders, naturally, assassinate either members of the military or the political parties of the foreign country that you were going to infiltrate, and if necessary some of your own members who were suspected of being foreign agents... We were concentrating strictly in Cuba at that particular time. Actually, they were operating out of Mexico, too."

Alleged JFK assassination connections

In an article published in the Florida Sun Sentinel on December 4, 1963, Jim Buchanan claimed that Sturgis had met Lee Harvey Oswald in Miami shortly before the assassination of John F. Kennedy. Buchanan claimed that Oswald had tried to infiltrate the Anti-Communist Brigade. When he was questioned by the FBI about this story, Sturgis claimed that Buchanan had misquoted him regarding his comments about Oswald.

According to a memo sent by L. Patrick Gray, Director of the FBI, to H. R. Haldeman in 1972: "Sources in Miami say he (Sturgis) is now associated with organized crime activities". In his book, Assassination of JFK (1977), Bernard Fensterwald claims that Sturgis was heavily involved with the Mafia, particularly with Santos Trafficante and Meyer Lansky activities in Florida.

The Rockefeller Commission of the U.S. Congress in 1974 investigated Frank Sturgis and E. Howard Hunt in connection with the 1963 assassination of President John F. Kennedy. Specifically, it investigated allegations that E. Howard Hunt and Frank Sturgis were CIA agents and were present in Dallas at the time of the assassination and could have fired the alleged shots from the grassy knoll.[3] Some support for Hunt's involvement, at any rate, came from a figure from the 1960s counterculture, Kerry Thornley, who believed he had, on several occasions from 1961-63, conversed with Hunt (who Thornley claimed used the alias "Gary Kirstein") regarding plans to assassinate John F. Kennedy while Thornley had been living in New Orleans. Newsweek magazine reported and printed photographs of three men, including two supposedly resembling Hunt and Sturgis, who were detained at the grassy knoll shortly after the assassination. The Newsweek article stated the official reports that the men were released and were only "railroad bums" who would find shelter sleeping in the boxcars of the trains located near the grassy knoll. According to Newsweek, the men were released without further inquiry.

According to the 1975 Rockefeller Commission report, Hunt testified that he had never met Sturgis before they were introduced by Bernard Barker in Miami in 1972. Sturgis testified to the same effect, except that he did not recall whether the introduction had taken place in late 1971 or early 1972. Sturgis further testified that while he had often heard of "Eduardo," a CIA political officer who had been active in the work of the Cuban Revolutionary Council in Miami prior to the Bay of Pigs operation in April 1961, he had never met him and did not know until 1971 or 1972 that "Eduardo" was E. Howard Hunt.[4]

In a deathbed statement [1] released in 2007, Howard Hunt names Sturgis as one of the participants in the JFK assassination.

Watergate burglary

On 17 June 1972, Sturgis, Virgilio Gonzalez, Eugenio Martinez, Bernard L. Barker and James W. McCord were arrested whilst installing electronic listening devices in the Democratic Party campaign offices located at the Watergate office complex in Washington. The phone number of E. Howard Hunt was found in address books of the burglars. Reporters were able to link the break-in to the White House. Bob Woodward, a reporter working for the Washington Post was told by a friend who was employed by the government that senior aides of President Richard Nixon had paid the burglars to obtain information about its political opponents.

Prison and later life

In January 1973, Sturgis, Hunt, Virgilio Gonzalez, Eugenio Martinez, Bernard L. Barker, Gordon Liddy and James W. McCord were convicted of conspiracy, burglary and wiretapping. While in prison, Sturgis gave an interview to Andrew St. George. Sturgis told St. George: "I will never leave this jail alive if what we discussed about Watergate does not remain a secret between us. If you attempt to publish what I've told you, I am a dead man."

St. George's article was published in True magazine in August 1974. Sturgis claims that the Watergate burglars had been instructed to find a particular document in the Democratic Party offices. This was a "secret memorandum from the Castro government" that included details of CIA covert actions. Sturgis said "that the Castro government suspected the CIA did not tell the whole truth about this operations even to American political leaders".

In 1976, Sturgis gave a series of interviews where he claimed that the assassination of John F. Kennedy had been organized by Fidel Castro and Che Guevara. According to Sturgis, Lee Harvey Oswald had been working in America as a Cuban agent.

In November 1977, Marita Lorenz gave an interview to the New York Daily News in which she claimed that a group called Operation 40, that included Sturgis and Lee Harvey Oswald, were involved in a conspiracy to kill both John F. Kennedy and Fidel Castro.

In August 1978, Victor Marchetti published an article about the assassination of John F. Kennedy in the Liberty Lobby newspaper, Spotlight. In the article, Marchetti argued that the House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA) had obtained a 1966 CIA memo that revealed Sturgis, E. Howard Hunt and Gerry Patrick Hemming had been involved in the plot to kill Kennedy. Marchetti's article also included a story that Marita Lorenz had provided information on this plot. Later that month, Joseph Trento and Jacquie Powers wrote a similar story for the Sunday News Journal.

The House Select Committee on Assassinations did not publish this alleged CIA memo linking its agents to the assassination of John F. Kennedy. Hunt now decided to take legal action against the Liberty Lobby and, in December 1981, he was awarded $650,000 in damages. Liberty Lobby appealed to the United States Court of Appeals. It was claimed that Hunt's attorney, Ellis Rubin, had offered a clearly erroneous instruction as to the law of defamation. The three-judge panel agreed and the case was retried. This time Mark Lane defended the Liberty Lobby against Hunt's action.

Lane eventually discovered Marchetti’s sources. The main source was William Corson. It also emerged that Marchetti had also consulted James Angleton and Alan J. Weberman before publishing the article. As a result of obtaining depositions from David Atlee Phillips, Richard Helms, G. Gordon Liddy, Stansfield Turner and Marita Lorenz, plus a skillful cross-examination by Lane of E. Howard Hunt, the jury decided in January 1995 that Marchetti had not been guilty of libel when he suggested that John F. Kennedy had been assassinated by people working for the CIA.

Lorenz also testified before the House Select Committee on Assassinations where she claimed that Sturgis had been one of the gunmen who fired on John F. Kennedy in Dallas. Sturgis testified that he had been engaged in various "adventures" relating to Cuba, which he believed to have been organized and financed by the CIA.

Sturgis denied that he had been involved in the assassination of Kennedy. Sturgis testified that he was in Miami throughout the day of the assassination, and his testimony was supported by that of his wife and a nephew of his wife. The House committee dismissed Lorenz's testimony, as they were unable to find any other evidence to support it.

In an obituary published December 5 1993, the New York Times quoted Sturgis' lawyer, Ellis Rubin, as saying that Sturgis died of cancer a week after he was admitted to a veterans hospital in Miami, Florida. It reported that doctors diagnosed lung cancer that had spread to his kidneys, and that he was survived by a wife, Jan, and a daughter.[5]

Notes

- ^ Will Ruha, proposal identifying fictional Hank Sturgis with Fiorini. For a contrary view, from Chapter 19 of the Rockefeller Commission report (denying suggestion that Sturgis took his present name from the Hunt character, or that the name change was associated in any way with Sturgis' knowing Hunt before 1971 or 1972), see "Were Watergate Conspirators Also JFK Assassins?".

- ^ Report to the President by the Commission on CIA Activities Within the United States Chapter 19

- ^ Gerald R. Ford Library, Summary Description of Rockefeller Commission Files

- ^ Report to the President by the Commission on CIA Activities Within the United States Chapter 19

- ^ "Frank A. Sturgis, Is Dead at 68; A Burglar in the Watergate Affair." Obituary, New York Times (December 5, 1993)