Aviation in World War I: Difference between revisions

Fixed typo: Inserted a period |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[Image:Nieuport.jpg|thumb|right|''Color [[Autochrome Lumière]] of a Nieuport Fighter in [[Aisne]], France 1917'']] |

[[Image:Nieuport.jpg|thumb|right|''Color [[Autochrome Lumière]] of a Nieuport Fighter in [[Aisne]], France 1917'']] |

||

One of the [[Technology during World War I|many innovations]] of [[World War I]], aircraft were first used for reconnaissance purposes and later as fighters and bombers Consequently, this was the first war which involved a struggle for control of the air, which turned it into another battlefield, alongside the battlefields of land and sea.<ref>Reconnaissance ballooning existed long before, as it was first used (rather tentatively) in the American Civil War.</ref>. |

One of the [[Technology during World War I|many innovations]] of [[World War I]], aircraft were first used for reconnaissance purposes and later as fighters and bombers. Consequently, this was the first war which involved a struggle for control of the air, which turned it into another battlefield, alongside the battlefields of land and sea.<ref>Reconnaissance ballooning existed long before, as it was first used (rather tentatively) in the American Civil War.</ref>. |

||

==History== |

==History== |

||

Revision as of 21:17, 23 January 2008

One of the many innovations of World War I, aircraft were first used for reconnaissance purposes and later as fighters and bombers. Consequently, this was the first war which involved a struggle for control of the air, which turned it into another battlefield, alongside the battlefields of land and sea.[1].

History

Prewar development

About ten years after the Wright brothers made the first powered flight, there was still much to be improved upon. Because of limitations of the engine power of the time, aircraft could only lift a certain amount of weight. They were made mostly of hardwood (braced with steel wires) and canvas doped with flammable liquid[2] to give them the stiffness required to form a wing surface. Aside from these primitive materials, the rudimentary aviation engineering of the time meant aircraft might suffer a structural failure pulling out of dives, resulting in shedding the wing or tail.

As early as 1909, these evolving flying machines were recognized to be not just toys, but weapons:

The sky is about to become another battlefield no less important than the battlefields on land and sea.... In order to conquer the air, it is necessary to deprive the enemy of all means of flying, by striking at him in the air, at his bases of operation, or at his production centers. We had better get accustomed to this idea, and prepare ourselves.

— Giulio Douhet (Italian staff officer), 1909[2]

In 1911, Captain Bertram Dickson, the first British military officer to fly, also correctly prophesied the military use of aircraft. He predicted aircraft would first be used for reconnaissance, but this would develop into each side trying to "hinder or prevent the enemy from obtaining information", which would eventually turn into a battle for control of the skies. This is exactly the sequence of events that would occur several years later.[2]

The first operational use of aircraft in war is accepted as 23 October 1911 in the Italo-Turkish War, when Captain Carlo Piazza made history’s first reconnaissance flight near Benghazi in a Blériot XI. [3]

The early years of war

The dawn of air combat

Aircraft were initially used as mobile observation vehicles[4] with the responsibility of mapping enemy positions below. This was an improvement over previous observation vehicles such as the zeppelin, which was slow, cumbersome, and difficult to launch, and the observation balloon, which had to be tethered to the ground.

As Dickson predicted, both the Entente and Central powers first used aircraft only for observation purposes. When rival observation planes crossed paths, the crews at first exchanged smiles and waves.[4] This soon progressed to throwing bricks, grenades, and other objects, even rope, which they hoped would tangle the enemy plane's propeller.[5] Eventually pilots began firing handheld firearms at enemy planes[4] Once the guns were mounted to the aircraft, the era of air combat began.

Aircraft

Aircraft of this early period included the Maurice Farman "Shorthorn" and "Longhorn", DFW B.I, Rumpler Taube, B.E. 2a, AEG B.II, Bleriot XI.

Even with their mechanical problems and technological limitations, observation planes played a critical role in the battles fought on the ground during 1914, especially in helping the Allies halt the German invasion of France. On August 22, 1914, British Captain L.E.O. Charlton and Lieutenant V.H.N. Wadham reported German General Alexander von Kluck’s army was starting to prepare to surround the BEF, contradicting all other intelligence. The British High Command listened to the pilots’ report and started a withdrawal toward Mons, undermining morale but saving the lives of 100,000 soldiers. Later, during the First Battle of Marne, observation planes discovered weak points and exposed flanks in the German lines, allowing the allies to take advantage of them. [6]

Problems mounting machine guns

Another major limitation was the early mounting of machine guns, which was awkward due to the propeller. It would seem most natural to place the gun between the pilot and the propeller, to be able to aim it as well as service it during a gun jam. However, this presents an obvious problem - the bullets would fly directly into the propeller.

Frenchman Roland Garros attempted to solve this problem by attaching metal wedges to the blades of his propeller, which he hoped would deflect bullets. Garros managed to score several kills with his deflector modification, yet it was still an inadequate and dangerous solution; as when Germany tried this, their steel-jacketed bullets shattered the wedges. It also tended to cause the prop to become unstable and fail to function correctly. The French Hotchkiss machine gun (as well as the Lewis gun) used by the Allies, fired more conventional copper- and brass-jacketed ammunition.

One of the methods used at this time was to mount the gun to fire above the propeller arc. This required the gun to be mounted on the top wing of biplanes and be propped up and secured by complicated, drag inducing mounting in monoplanes. Because the gun could not be reached, it could not be serviced during a gun jam,[citation needed] nor could ammunition belts or drums be changed.[citation needed] Eventually the excellent Foster mounting became more or less the standard way of mounting a Lewis gun in this position in the R.F.C. - this allowed the gun to slide backward for drum changing, and also to be fired at an upward angle, a very effective way of attacking an enemy from the "blind spot" under his tail. This type of mounting was still only possible for a biplane with a top wing positioned near the apex of the propeller's arc - it put considerable strain on the fragile wing structures of the period, and it was much less rigid than a gun mounting on the fuselage - producing a greater "scatter" of bullets, especially at anything but very short range.

Another solution was the use of pusher types, widely used by the French and British in the early part of the war. The pusher design had the engine and propeller behind the pilot, facing backward, and "pushing" rather than "pulling" the plane through the air. This provided the opportunity to optimally mount the gun, which could be fired directly forward without an obstructing propeller, and of course reloaded and repaired in-flight. The drawback was pusher planes - because of the struts and rigging necessary to hold their tail units, and the extra drag this entailed-tended at best to have an inferior performance to a "tractor" type with the same engine.

The principle of a synchronized gun - essentially allowing the engine to fire the gun at the same speed as the turning propeller and allowing the bullets to pass unimpeded between the blades - had actually occurred to inventors in Britain, France, and Germany well before the war, and several mechanisms had been designed. There was however a great reluctance to try the idea out in practice, since it was all too obvious what would happen if the system went wrong, as well as the prospect of it falling in the hands of an enemy who did not yet have it. Fokker were the first aircraft manufacturer to "bite the bullet" and actually offer this solution to the German Air Service, producing the famous Eindekker fighters. Crude as these little monoplanes were, they led in part to a period of German air dominance, known as the "Fokker Scourge" by the Allies because of the losses inflicted. The psychological effect exceeded the material - the Allies had up to now been more or less unchallenged in the air, and the vulnerability of their older reconnaissance aircraft, especially the British B.E.2 and French Farman pushers, came as a very nasty shock.

The Lewis gun, used on many early Allied aircraft, was very hard to synchronize due to its firing cycle starting with an empty, and open, breech, ready to receive a round. Although some synchronized Lewis mountings were made, especially in the R.N.A.S) these were never entirely satisfactory. The Maxim guns used by both the Allies (as the Vickers) and Germany (as the LMG 14 Parabellum and LMG 08 Spandau guns) had a firing cycle that started with a bullet already in the breech and the breech closed, which meant the firing of the bullet was the next step in the cycle, making synchronizing them considerably easier.

1915: The Fokker Scourge

In 1915, Anthony Fokker designed the interrupter gear, which turned the tide of war in Germany's favor. This ingenious device mechanically linked the gun to the propeller, stopping the fire when a propeller blade passed in front of the machinegun muzzle. This was first fitted in the spring of 1915 to the production prototypes of the Fokker Eindecker, known as the M.5K/MG, making it top-of-the-line in design, maneuverability (although the Eindecker used wing warping for roll control), and most importantly, gun placement. Leutnant Kurt Wintgens, on July 1, 1915, scored the earliest known victory for a synchronized gun-equipped fighter with his M.5K/MG over a two-seat Morane Saulnier Parasol near Luneville, France. The result was devastating for the Allied powers, and gave the Germans almost total control of the air. Soon Allied planes were forced to flee for home at the mere sight of German monoplanes. A solution was needed, and quickly.

The E.III's foil came in the form of the Nieuport 11, a tractor biplane and, as needed, a cowl gun. The key event which allowed the Allies to reverse-engineer the German technology occurred when a German pilot became lost in heavy fog over France. The pilot and plane were captured when it landed, giving the Allies access to its technology.

Another plane contributing to the end of the Fokker Scourge was the British pusher Airco DH.2. It suffered from mechanical reliability problems, but was far superior to the E.III.

The Fokker E-III, Airco DH-2, and Nieuport 11 would be the first in a long line of fighter aircraft used by both sides during the war. Fighters were primarily used to shoot down enemy planes, mainly the two-seaters used for reconnaissance and bombing missions. Because of this, another key role of fighter planes was to protect their own two-seaters from enemy fighters while they carried out their mission. Fighters were also used to attack ground targets with small loads of bombs and by strafing.

Bloody April

In April 1917, the Allies launched a joint offensive, the British attacking near Arras in Artois, while the French Nivelle Offensive was launched on the Aisne. Air forces were called on to provide support, predominantly in reconnaissance and artillery spotting.

However, the Germans were prepared for the offensive, and were equipped with the new Albatros D-III, "the best fighting scout on the Western Front"[7] at the time.

The month became known as Bloody April by the Allied air forces. The Royal Flying Corps suffered particularly severe losses. However, they managed to keep the German Air Force on the defensive, largely preventing them from using their planes on bombing or reconnaissance missions to assist their troops on the ground.

Shortly after "Bloody April", the Allies re-equipped their squadrons with new planes such as the Sopwith Pup, and S.E.5a which helped tip the balance back in their favor. The Germans responded with new types as well, such as the Fokker Dr.I, which were in turn countered by the British Sopwith Camel and French SPAD S.XIII. As a result, the Allies were able to maintain general air superiority toward the end of the year, which was in general maintained for the rest of the war.

Up to 1918: the final years of war

The final year of the war (1918) saw increasing shortages of supplies on the side of the Central Powers. Captured Allied planes were scrounged for every available material, even to the point of draining the lubricants from damaged engines just to keep one more German plane flyable.

Manfred von Richthofen, the famed Red Baron credited with around 80 victories, was killed in April, possibly by an Australian anti-aircraft machinegunner (although Royal Air Force pilot Captain Arthur Roy Brown was officially credited), and the leadership of Jagdgeschwader 1 eventually passed to Hermann Göring.

Germany introduced the Fokker D.VII, both loved and loathed to the point surrender of all surviving examples was specifically ordered by the victorious Allies.

This year also saw the United States increasingly involved. While American volunteers had been flying in Allied squadrons since the early years of the war, not until 1918 did ll-American squadrons begin patrolling the skies above the trenches. At first, the Americans were largely supplied with second-rate weapons and obsolete planes, such as the Nieuport 28. As American numbers grew, equipment improved, including the SPAD S.XIII, one of the best French planes in the war.

Impact

The day has passed when armies on the ground or navies on the sea can be the arbiter of a nation's destiny in war. The main power of defense and the power of initiative against an enemy has passed to the air.

By the war's end, the impact of air missions on the ground war was in retrospect mainly tactical - strategic bombing, in particular, was still very rudimentary indeed. This was partly due to its restricted funding and use, as it was, after all, a new technology. Some, such as then-Brigadier General William "Billy" Mitchell, commander of all American air combat units in France, claimed "the only damage that has come to [Germany] has been through the air".[8] Mitchell was famously controversial in his view that the future of war was not on the ground or at sea, but in the air:

Anti-aircraft weaponry

Though aircraft still functioned as vehicles of observation, increasingly it was used as a weapon in itself. Dog fights erupted in the skies over the front lines - planes went down in flames and heroes were born. From this air-to-air combat, the need grew for better planes and gun armament. Aside from machineguns, air-to-air rockets were also used, such as the Le Prieur rocket against balloons and airships.

This need for improvement was not limited to air-to-air combat. On the ground, methods developed before the war were being used to deter enemy planes from observation and bombing. Anti-aircraft artillery rounds were fired into the air and exploded into clouds of smoke and fragmentation, called archie by the British.

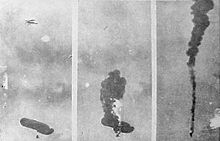

Anti-aircraft artillery defenses were increasingly used around observation balloons, which became frequent targets of enemy fighters equipped with special incendiary bullets. Because balloons were so flammable, due to the hydrogen used to inflate them, observers were given parachutes, enabling them to jump to safety. Ironically, only a few aircrew had this option, due in part to a mistaken belief they inhibited aggressiveness, and in part to early aircraft being unable to lift their significant weight.

Bombing and reconnaissance

As the stalemate developed on the ground, with both sides unable to advance even a few hundred yards without a major battle and thousands of casualties, aircraft became greatly valued for their role gathering intelligence on enemy positions and bombing the enemy's supplies behind the trench lines. Large planes with a pilot and an observer were used to scout enemy positions and bomb their supply bases. Because they were large and slow, these planes made easy targets for enemy fighter planes. As a result, both sides used fighter aircraft to both attack the enemy's two-seat planes and protect their own while carrying out their missions.

While the two-seat bombers and reconnaissance planes were slow and vulnerable, they were not defenseless. Two-seaters had the advantage of both forward- and rearward- firing guns. Typically, the pilot controlled fixed guns behind the propeller, similar to guns in a fighter plane, while the observer controlled one with which he could cover the arc behind the plane. Also, pursuing a diving two-seater was hazardous for a fighter pilot, as it would place the fighter directly in the rear-gunner's line of fire; several high scoring aces of the war were shot down by "lowly" two-seaters, including Raoul Lufbery and Robert Little.

Template:Multi-video start Template:Multi-video item Template:Multi-video end

Strategic bombing

The first ever aerial bombardment of civilians was during World War I. On January 19, 1915, two German Zeppelins dropped 24 fifty-kilogram high-explosive bombs and ineffective three-kilogram incendiaries on Great Yarmouth, Sheringham, King's Lynn, and the surrounding villages. In all, four people were killed, sixteen injured, and monetary damage was estimated at £7,740, although the public and media reaction were out of proportion to the death toll.[10]

There were a further nineteen raids in 1915, in which 37 tons of bombs were dropped, killing 181 people and injuring 455. Raids continued in 1916. London was accidentally bombed in May, and, in July, the Kaiser allowed directed raids against urban centres. There were 23 airship raids in 1916 in which 125 tons of ordnance were dropped, killing 293 people and injuring 691. Gradually British air defenses improved. In 1917 and 1918 there were only eleven Zeppelin raids against England, and the final raid occurred on August 5 1918, which resulted in the death of KK Peter Strasser, commander of the German Naval Airship Department. By the end of the war, 51 raids had been undertaken, in which 5,806 bombs were dropped, killing 557 people and injuring 1,358.

The Zeppelin raids were complemented by the Gotha G bombers from 1917, which were the first heavier than air bombers to be used for strategic bombing. It has been argued that the raids were effective far beyond material damage in diverting and hampering wartime production, and diverting twelve squadrons and over 10,000 men to air defenses. The calculations which were performed on the number of dead to the weight of bombs dropped would have a profound effect on the attitudes of the British authorities and population in the interwar years.

Observation balloons

Manned observation balloons floating high above the trenches were used as stationary reconnaissance points on the front lines, reporting enemy troop positions and directing artillery fire. Balloons commonly had a crew of two equipped with parachutes: upon an enemy air attack on the flammable balloon, the crew would parachute to safety. Recognized for their value as observer platforms, observation balloons were important targets of enemy aircraft. To defend against air attack, they were heavily protected by large concentrations antiaircraft guns and patrolled by friendly aircraft. Blimps and balloons helped contribute to the stalemate of the trench warfare of World War I, and contributed to air to air combat for air superiority because of their significant reconnaissance value.

In order to encourage their pilots to attack enemy balloons whenever they were found, both sides counted downing an enemy balloon as an "air-to-air" kill, with the same value as shooting down an enemy plane. Some pilots, known as balloon busters, became particularly distinguished by their prowess at shooting down enemy balloons. Perhaps the best known of these was American ace Frank Luke: 14 of his 18 kills were enemy balloons.

Notable aces

| Name | Confirmed Victories | Country | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Manfred von Richthofen † | 80 | Germany | The Red Baron, Pour le Mérite |

| René Fonck | 75 | France | Top Allied ace, and all-time Allied Ace of Aces in all conflicts. |

| Edward Mannock † | 73 disputed | UK | Top scoring United Kingdom ace.-disputed |

| Billy Bishop | 72 disputed | Canada | Top-scoring British Empire ace.-disputed |

| Raymond Collishaw | 62 | Canada | Top Royal Naval Air Service ace. |

| Ernst Udet | 62 | Germany | Second highest scoring German ace. |

| James McCudden † | 57 | UK | Victoria Cross, Croix de Guerre. One of the longest serving aces (from 1913 to 1918) |

| Georges Guynemer † | 53 | France | First French ace to attain 50 victories. |

| Roderic Dallas † | 51 (disputed) | Australia | Australian.[citation needed] |

| William Barker | 50 | Canada | |

| Werner Voss † | 48 | Germany | One time friendly rival of Manfred von Richthofen |

| George Edward Henry McElroy † | 47 | UK | Highest-scoring Irish-born ace. |

| Robert Little † | 47 | Australia (serving under Britain) | |

| Albert Ball † | 44 | UK | Victoria Cross |

| Charles Nungesser | 43 | France | Légion d'Honneur, Médaille Militaire |

| Lothar von Richthofen | 40 | Germany | Pour le Mérite, brother of Manfred. |

| Oswald Boelcke † | 40 | Germany | Pour le Mérite Legendary German air hero, killed in 1916. |

| Julius Buckler | 36 | Germany | Pour le Mérite |

| Theo Osterkamp | 32 (plus 6 in World War II) | Germany | |

| Francesco Baracca † | 34 | Italy | Top-scoring Italy ace. |

| Karl Allmenröder † | 30 | Germany | Pour le Mérite |

| Keith Park | 30 | New Zealand | Leading New Zealand ace, flying with Australia. Croix de Guerre |

| A. H. "Harry" Cobby | 30 | Australia | Once thought to be highest scoring ace.[citation needed] |

| Eddie Rickenbacker | 26 | United States | Top US ace |

| Hermann Göring | 22 | Germany | Pour le Mérite |

| William C. Lambert | 21.5 | United States | |

| Aleksandr Kazakov | 20 | Imperial Russia | Top Russian ace. |

| Frank Luke † | 18 | United States | Medal of Honor "Arizona Balloon Buster" |

| Raoul Lufbery † | 17 | United States and France | Leader of the Lafayette Escadrille |

| Max Immelmann † | 15 | Germany | Pour le Mérite |

| Field Kindley | 12 | United States, served under Britain | |

| Indra Lal Roy † | 10 | India | India's only ace. |

| Donald Cunnell † | 9 | UK | Shot down Manfred von Richthofen |

| Lanoe Hawker † | 9 | UK | Victoria Cross. Britain's first ace. |

| Christopher Draper | 9 | UK | "The Mad Major". Croix de Guerre |

| Roland Garros † | 5 | France | First nonstop flight across the Mediterranean Sea (1913). Attached metal deflectors to propellor in order to have a forward-firing gun. |

Notable aircraft

See also Category:World War I aircraft.

Notes

- ^ Reconnaissance ballooning existed long before, as it was first used (rather tentatively) in the American Civil War.

- ^ a b c Knights of the Air (1980) by Ezra Bowen, part of Time-Life's The Epic of Flight series. Pg. 24, 26

- ^ p.4

- ^ a b c An Illustrated History of World War One, at http://www.wwiaviation.com/earlywar.html

- ^ Great Battles of World War I by Major-General Sir Jeremy Moore, p. 136

- ^ http://www.centennialofflight.gov/essay/Air_Power/WWI-reconnaissance/AP2.htm [1]

- ^ Fitzsimons, Bernard, ed. The Twentieth Century Encyclopedia of Weapons and Warfare (London: Phoebus, 1978), Volume 1, "Albatros D", p.65

- ^ a b "Leaves From My War Diary" by General William Mitchell, in Great Battles of World War I: In The Air (Signet, 1966), pp.192 & 193 (November 1918).

- ^ This quote was also mentioned in Time magazine, June 22, 1942 [2], some seven months after the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor, which Mitchell accurately predicted in 1924.

- ^ Ward's Book of Days. Pages of interesting anniversaries. What happened on this day in history. January 19th. On this day in history in 1915, German zeppelins bombed Britain.

See also

Main articles

Other articles

References

- The Great War, television documentary by the BBC.

- Pearson, George, Aces: A Story of the First Air War, historical advice by Brereton Greenhous and Philip Markham, NFB, 1993. Contains assertion aircraft created trench stalemate.

- Winter, Denis. First of the Few. London: Allen Lane/Penguin, 1982. Coverage of the British air war, with extensive bibliographical notes.

- Morrow, John. German Air Power in World War I. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1982. Contains design and production figures, as well as economic influences.

- Editors of American Heritage. History of WW1. Simon & Schuster, 1964.

External links

- Rosebud's WWI and Early Aviation Image Archive

- Bombing during World War I

- Flyboys - World War I aviation movie

- - Aerial Russia - the Romance of the Giant Airplane - aviation in Russian before and during WWI - online book

Italian aircraft: