Picts: Difference between revisions

| [pending revision] | [pending revision] |

m Reverted edits by 76.24.122.7 (talk) to last version by Mike Christie |

|||

| Line 78: | Line 78: | ||

==Language== |

==Language== |

||

{{main|1=Pictish language}} |

{{main|1=Pictish language}} |

||

The Pictish language has not survived. Evidence is limited to place names and to the names of people found on monuments and the contemporary records. |

The Pictish language, if such a thing ever existed, has not survived. Evidence is limited to place names and to the names of people found on monuments and the contemporary records. |

||

The evidence of [[toponym|place-names]] and [[Onomastics|personal names]] argue strongly that the Picts spoke [[Insular Celtic languages]] related to the more southerly [[Brythonic languages]].<ref>Forsyth, ''Language in Pictland'', Price "Pictish", Taylor, "Place names", Watson, ''Celtic Place Names''. For K.H. Jackson's views, see "The Language of the Picts" in Wainwright (ed.) ''The Problem of the Picts.''</ref> A number of inscriptions have been argued to be non-Celtic, and on this basis, it has been suggested that non-Celtic languages were also in use.<ref>Jackson, "The Language of the Picts", discussed by Forsyth, ''Language in Pictland''.</ref> |

The evidence of [[toponym|place-names]] and [[Onomastics|personal names]] argue strongly that the Picts spoke [[Insular Celtic languages]] related to the more southerly [[Brythonic languages]].<ref>Forsyth, ''Language in Pictland'', Price "Pictish", Taylor, "Place names", Watson, ''Celtic Place Names''. For K.H. Jackson's views, see "The Language of the Picts" in Wainwright (ed.) ''The Problem of the Picts.''</ref> A number of inscriptions have been argued to be non-Celtic, and on this basis, it has been suggested that non-Celtic languages were also in use.<ref>Jackson, "The Language of the Picts", discussed by Forsyth, ''Language in Pictland''.</ref> |

||

Revision as of 17:54, 2 April 2008

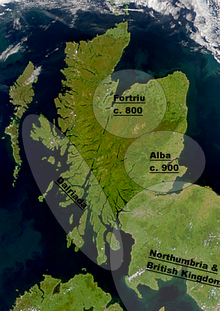

The Picts were a confederation of tribes in what later was to become central and northern Scotland from Roman times until the 10th century. They lived to the north of the Forth and Clyde. They are often assumed to have been the descendants of the Caledonii and other tribes named by Roman historians or found on the world map of Ptolemy, though the evidence for this connection is circumstantial and the issue of "Pict" origins remains controversial among historians. Pictland, also known as Pictavia, became the Kingdom of Alba during the 10th century and the Picts became the Fir Alban, the men of Scotland.

Archaeology gives some impression of the society of the Picts. Although very little in the way of Pictish writing has survived, Pictish history since late 6th century is known from a variety of sources, including saints' lives, such as that of Columba by Adomnán, and various Irish annals. Although the popular impression of the Picts may be one of an obscure, mysterious people, this is far from being the case. When compared with the generality of Northern, Central and Eastern Europe in Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages, Pictish history and society are well attested.[1]

Etymology of names

The name by which the Picts called themselves is unknown. The Greek word Πικτοί (Latin Picti) first appears in a panegyric written by Eumenius in AD 297 and is taken to mean "painted or tattooed people" (Latin pingere "paint"). The Gaels of Ireland and the Scottish kingdom of Dál Riata called the Picts Cruithne, (Old Irish cru(i)then-túath), presumably from Proto-Celtic *kwriteno-toutā. There were also people referred to as Cruithne in Ulster, in particular the kings of Dál nAraidi.[2] The Britons (later the Welsh and Cornish) in the south knew them, in the P-Celtic form of "Cruithne", as Prydyn; the terms "Britain" and "Briton" come from the same root.[3] Their Old English name gave the modern Scots form Pechts.[4]

History

The means by which the Pictish confederation formed in Late Antiquity from a number of tribes are as obscure as the processes which created the Franks, the Alamanni and similar confederations in Germany. The presence of the Roman Empire, unfamiliar in size, culture, political systems and ways of making war, should be noted. Nor can we ignore the wealth and prestige that control of trade with Rome offered.[5]

Pictland had previously been described as the home of the Caledonii.[6] Other tribes said to have lived in the area included the Verturiones, Taexali and Venicones.[7] Except for the Caledonians, the names may be second- or third-hand: perhaps as reported to the Romans by speakers of Brythonic or Gaulish languages.[8]

Pictish recorded history begins in the Dark Ages. It appears that they were not the dominant power in Northern Britain for the entire period. Firstly the Gaels of Dál Riata dominated the region, but suffered a series of defeats in the first third of the 7th century.[9] The Angles of Bernicia overwhelmed the adjacent British kingdoms, and the neighbouring Anglian kingdom of Deira (Bernicia and Deira later being called Northumbria), was to become the most powerful kingdom in Britain.[10] The Picts were probably tributary to Northumbria until the reign of Bridei map Beli, when the Anglians suffered a defeat at the battle of Dunnichen which halted their expansion northwards. The Northumbrians continued to dominate southern Scotland for the remainder of the Pictish period.

In the reign of Óengus mac Fergusa (729–761), Dál Riata was very much subject to the Pictish king. Although it had its own kings from the 760s, it appears that Dál Riata did not recover.[11] A later Pictish king, Caustantín mac Fergusa (793–820), placed his son Domnall on the throne of Dál Riata (811–835).[12] Pictish attempts to achieve a similar dominance over the Britons of Alt Clut (Dumbarton) were not successful.[13]

The Viking Age brought great changes in Britain and Ireland, no less in Scotland than elsewhere. The kingdom of Dál Riata was destroyed, certainly by the middle of the 9th century, when Ketil Flatnose is said to have founded the Kingdom of the Isles. Northumbria too succumbed to the Vikings, who founded the Kingdom of York, and the kingdom of Strathclyde was also greatly affected. The king of Fortriu Eógan mac Óengusa, the king of Dál Riata Áed mac Boanta, and many more, were killed in a major battle against the Vikings in 839.[14] The rise of Cínaed mac Ailpín (Kenneth MacAlpin) in the 840s, in the aftermath of this disaster, brought to power the family who would preside over the last days of the Pictish kingdom and found the new kingdom of Alba, although Cínaed himself was never other than king of the Picts.

In the reign of Cínaed's grandson, Caustantín mac Áeda (900–943), the kingdom of the Picts became the kingdom of Alba. The change from Pictland to Alba may not have been noticeable at first; indeed, as we do not know the Pictish name for their land, it may not have been a change at all. The Picts, along with their language, did not disappear suddenly. The process of Gaelicisation, which may have begun generations earlier, continued under Caustantín and his successors. When the last inhabitants of Alba were fully Gaelicised, becoming Scots, probably during the 11th century, the Picts were soon forgotten.[15] Later they would reappear in myth and legend.[16]

Kings and kingdoms

The early history of Pictland is, as has been said, unclear. In later periods multiple kings existed, ruling over separate kingdoms, with one king, sometimes two, more or less dominating their lesser neighbours.[17] De Situ Albanie, a late document, the Pictish Chronicle, the Duan Albanach, along with Irish legends, have been used to argue the existence of seven Pictish kingdoms. These are as follows; those in bold are known to have had kings, or are otherwise attested in the Pictish period:

- Cait, situated in modern Caithness and Sutherland

- Ce, situated in modern Mar and Buchan

- Circinn, perhaps situated in modern Angus and the Mearns[18]

- Fib, the modern Fife, known to this day as 'the Kingdom of Fife'

- Fidach, location unknown

- Fotla, modern Atholl (Ath-Fotla)[19]

- Fortriu, cognate with the Verturiones of the Romans; recently shown to be centered around Moray[20]

More small kingdoms may have existed. Some evidence suggests that a Pictish kingdom also existed in Orkney.[21] De Situ Albanie is not the most reliable of sources, and the number of kingdoms, one for each of the seven sons of Cruithne, the eponymous founder of the Picts, may well be grounds enough for disbelief.[22] Regardless of the exact number of kingdoms and their names, the Pictish nation was not a united one.

For most of Pictish recorded history the kingdom of Fortriu appears dominant, so much so that king of Fortriu and king of the Picts may mean one and the same thing in the annals. This was previously thought to lie in the area around Perth and the southern Strathearn, whereas recent work has convinced those working in the field that Moray (a name referring to a very much larger area in the High Middle Ages than the county of Moray), was the core of Fortriu.[23]

The Picts are often said to have practised matrilineal succession on the basis of Irish legends and a statement in Bede's history. In fact, Bede merely says that the Picts used matrilineal succession in exceptional cases.[24] The kings of the Picts when Bede was writing were Bridei and Nechtan, sons of Der Ilei, who indeed claimed the throne through their mother Der Ilei, daughter of an earlier Pictish king.[25]

In Ireland, kings were expected to come from among those who had a great-grandfather who had been king.[26] Kingly fathers were not frequently succeeded by their sons, not because the Picts practised matrilineal succession, but because they were usually followed by their brothers or cousins, more likely to be experienced men with the authority and the support necessary to be king.[27]

The nature of kingship changed considerably during the centuries of Pictish history. While kings had to be successful war leaders to maintain their authority, kingship became rather less personalised and more institutionalised during this time. Bureaucratic kingship was still far in the future when Pictland became Alba, but the support of the church, and the apparent ability of a small number of families to control the kingship for much of the period from the later 7th century onwards, provided a considerable degree of continuity. In the much same period, the Picts' neighbours in Dál Riata and Northumbria faced considerable difficulties as the stability of succession and rule which they had previously benefitted from came to an end.[28]

The later Mormaers are thought to have originated in Pictish times, and to have been copied from, or inspired by, Northumbrian usages.[29] It is unclear whether the Mormaers were originally former kings, royal officials, or local nobles, or some combination of these. Likewise, the Pictish shires and thanages, traces of which are found in later times, are thought to have been adopted from their southern neighbours.[30]

Society

The archaeological record provides evidence of the material culture of the Picts. It tells of a society not readily distinguishable from its similar Gaelic and British neighbours, nor very different from the Anglo-Saxons to the south.[31] Although analogy and knowledge of other "Celtic" societies may be a useful guide, these extended across a very large area. Relying on knowledge of pre-Roman Gaul, or 13th century Ireland, as a guide to the Picts of the 6th century may be misleading if analogy is pursued too far.[32]

As with most peoples in the north of Europe in Late Antiquity, the Picts were farmers living in small communities. Cattle and horses were an obvious sign of wealth and prestige, sheep and pigs were kept in large numbers, and place names suggest that transhumance was common. Animals were small by later standards, although horses from Britain were imported into Ireland as breed-stock to enlarge native horses. From Irish sources it appears that the élite engaged in competitive cattle-breeding for size, and this may have been the case in Pictland also. Carvings show hunting with dogs, and also, unlike in Ireland, with falcons. Cereal crops included wheat, barley, oats and rye. Vegetables included kale, cabbage, onions and leeks, peas and beans, turnips and carrots, and some types no longer common, such as skirret. Plants such as wild garlic, nettles and watercress may have been gathered in the wild. The pastoral economy meant that hides and leather were readily available. Wool was the main source of fibres for clothing, and flax was also common, although it is not clear if it was grown for fibres, for oil, or as a foodstuff. Fish, shellfish, seals and whales were exploited along coasts and rivers. The importance of domesticated animals argues that meat and milk products were a major part of the diet of ordinary people, while the élite would have eaten a diet rich in meat from farming and hunting.[33]

No Pictish counterparts to the areas of denser settlement around important fortresses in Gaul and southern Britain, or any other significant urban settlements, are known. Larger, but not large, settlements existed around royal forts, such as at Burghead, or associated with religious foundations.[34] No towns are known in Scotland until the 12th century.[35]

The technology of everyday life is not well recorded, but archaeological evidence shows it to have been similar to that in Ireland and Anglo-Saxon England. Recently evidence has been found of watermills in Pictland. Kilns were used for drying kernels of wheat or barley, not otherwise easy in the changeable, temperate climate.[36]

The early Picts are associated with piracy and raiding along the coasts of Roman Britain. Even in the Late Middle Ages, the line between traders and pirates was unclear, so that Pictish pirates were probably merchants on other occasions. It is generally assumed that trade collapsed with the Roman Empire, but this is to overstate the case. There is only limited evidence of long-distance trade with Pictland, but tableware and storage vessels from Gaul, probably transported up the Irish Sea, have been found. This trade may have been controlled from Dunadd in Dál Riata, where such goods appear to have been common. While long-distance travel was unusual in Pictish times, it was far from unknown as stories of missionaries, travelling clerics and exiles show.[37]

Brochs are popularly associated with the Picts. Although these were built earlier in the Iron Age, with construction ending around 100 AD, they remained in use into and beyond the Pictish period.[38] Crannogs, which may originate in Neolithic Scotland, may have been rebuilt, and some were still in use in the time of the Picts.[39] The most common sort of buildings would have been roundhouses and rectangular timbered halls.[40] While many churches were built in wood, from the early 8th century, if not earlier, some were built in stone.[41]

The Picts are often said to have tattooed themselves, but evidence for this is limited. Naturalistic depictions of Pictish nobles, hunters and warriors, male and female, without obvious tattoos, are found on monumental stones. These stones include inscriptions in Latin and Ogham script, not all of which have been deciphered. The well known Pictish symbols found on stones, and elsewhere, are obscure in meaning. A variety of esoteric explanations have been offered, but the simplest conclusion may be that these symbols represent the names of those who had raised, or are commemorated on, the stones. Pictish art can be classed as Celtic, and later as Insular.[42] Irish poets portrayed their Pictish counterparts as very much like themselves.[43]

Religion

Early Pictish religion is presumed to have resembled Celtic polytheism in general, although only place names remain from the pre-Christian era. The date at which the Pictish elite converted to Christianity is uncertain, but there are traditions which place Saint Palladius in Pictland after leaving Ireland, and link Abernethy with Saint Brigid of Kildare.[44] Saint Patrick refers to "apostate picts", while the poem Y Gododdin does not remark on the picts as pagans.[45] Bede wrote that Saint Ninian (identified with Saint Finnian of Moville, who died c. 589), had converted the southern Picts.[46] Recent archaeological work at Portmahomack places the foundation of the monastery there, an area once assumed to be among the last converted, in the late 6th century.[47] This is contemporary with Bridei mac Maelchon and Columba, but the process of establishing Christianity throughout Pictland will have extended over a much longer period.

Pictland was not solely influenced by Iona and Ireland. It also had ties to churches in Northumbria, as seen in the reign of Nechtan mac Der Ilei. The reported expulsion of Ionan monks and clergy by Nechtan in 717 may have been related to the controversy over the dating of Easter, and the manner of tonsure, where Nechtan appears to have supported the Roman usages, but may equally have been intended to increase royal power over the church.[48] Nonetheless, the evidence of place names suggests a wide area of Ionan influence in Pictland.[49] Likewise, the Cáin Adomnáin (Law of Adomnán, Lex Innocentium) counts Nechtan's brother Bridei among its guarantors.

The importance of monastic centres in Pictland was not perhaps as great as in Ireland. In areas which had been studied, such as Strathspey and Perthshire, it appears that the parochial structure of the High Middle Ages existed in early medieval times. Among the major religious sites of eastern Pictland were Portmahomack, Cennrígmonaid (later St Andrews), Dunkeld, Abernethy and Rosemarkie. It appears that these are associated with Pictish kings, which argues for a considerable degree of royal patronage and control of the church.[50]

The cult of Saints was, as throughout Christian lands, of great importance in later Pictland. While kings might patronise great Saints, such as Saint Peter in the case of Nechtan, and perhaps Saint Andrew in the case of the second Óengus mac Fergusa, many lesser Saints, some now obscure, were important. The Pictish Saint Drostan appears to have had a wide following in the north in earlier times, although all but forgotten by the 12th century. Saint Serf of Culross was associated with Nechtan's brother Bridei.[51] It appears, as is well known in later times, that noble kin groups had their own patron saints, and their own churches or abbeys.[52]

Art

Pictish Art appears on stones, metalwork and small objects of stone and bone. It has similarities to both Saxon and Irish art. Primarily Pictish art is found on the many Pictish stones that are located all over Pictland, from Inverness to Lanarkshire. An illustrated catalogue of these stones was produced by J. Romilly Allen as part of "The Early Church Monuments of Scotland", with lists of their symbols and patterns. The symbols and patterns consist of animals, the "bill", the "mirror and comb", "the spectacles" and "the crescent and V-rod". There are also bosses and lenses with pelta and spiral designs. The patterns are curvilinear with hatchings.

Pictish metalwork is found throughout Pictland and also further south. The items found in the south consist of heavy silver chains over 0.5m long, and may have been gifts or carried off by raiders. It has been suggested by Stevenson (in Wainwright, The Problem of the Picts) that these chains formed part of "choker" necklaces.

Language

The Pictish language, if such a thing ever existed, has not survived. Evidence is limited to place names and to the names of people found on monuments and the contemporary records. The evidence of place-names and personal names argue strongly that the Picts spoke Insular Celtic languages related to the more southerly Brythonic languages.[53] A number of inscriptions have been argued to be non-Celtic, and on this basis, it has been suggested that non-Celtic languages were also in use.[54]

The absence of surviving written material in Pictish does not mean a pre-literate society. The church certainly required literacy, and could not function without copyists to produce liturgical documents. Pictish iconography shows books being read, and carried, and its naturalistic style gives every reason to suppose that such images were of real life. Literacy was not widespread, but among the senior clergy, and in monasteries, it would have been common enough.[55]

Place-names often allow us to deduce the existence of historic Pictish settlements in Scotland. Those prefixed with "Aber-", "Lhan-", or "Pit-" indicate regions inhabited by Picts in the past (for example: Aberdeen, Lhanbryde, Pitmedden, Pittodrie etc). Some of these, such as "Pit-" (portion, share), were formed after Pictish times, and may refer to previous "shires" or "thanages".[56]

The evidence of place-names may also reveal the advance of Gaelic into Pictland. As noted, Atholl, meaning New Ireland, is attested in the early 8th century. This may be an indication of the advance of Gaelic. Fortriu also contains place-names suggesting Gaelic settlement, or Gaelic influences.[57]

See also

|

|

Notes

- ^ Sources for Pictish history include Irish Annals - the Annals of Ulster, Tigernach, Innisfallen, Ireland (the Four Masters), and Clonmacnoise all report events in Scotland, some frequently; the Lebor Bretnach, Scottish recension of the Historia Britonum of Nennius; the history and continuatation of Bede; the Historia Regum Anglorum of Symeon of Durham; the Annales Cambriae; saints' lives; and others.

- ^ The Cruithni are discussed by Byrne, Irish Kings and High-Kings, pp. 106–109, Ó Cróinín, Early Medieval Ireland, pp. 48–50.

- ^ Old Irish cruth and Welsh pryd are the Q- and P-Celtic forms respectively of a word meaning "form" or "shape": taken to be a reference to the Picts' practice of tattooing their bodies. See The Scottish Place-Name Society and MacBain's Dictionary.

- ^ The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle has pihtas and pehtas.

- ^ See the discussion of the creation of the Frankish Confederacy in Geary, Before France, chapter 2.

- ^ e.g. by Tacitus, Ptolemy, and as the Dicalydonii by Ammianus Marcellinus. Note that Ptolemy refers to the sea to the west of Scotland as the Oceanus Duecaledonius.

- ^ e.g. Ptolemy, Ammianus Marcellinus.

- ^ Caledonii is attested from a grave marker in Roman Britain.

- ^ At Degsastan in the first decade of the century and several times under Domnall Brecc in the third and fourth decades.

- ^ For the kingdoms of Bernicia, and Northumbria, see e.g. Higham, The Kingdom of Northumbria.

- ^ Broun, "Pictish Kings", attempts to reconstruct the confused late history of Dál Riata. The silence in the Irish Annals is ignored by Bannerman in "The Scottish Takeover of Pictland and the relics of Columba".

- ^ After Broun, "Pictish Kings", but the later history of Dál Riata is very obscure.

- ^ Cf. the failed attempts by Óengus mac Fergusa.

- ^ Annals of Ulster (s.a. 839): "The (Vikings) won a battle against the men of Fortriu, and Eóganán son of Aengus, Bran son of Óengus, Aed son of Boanta, and others almost innumerable fell there."

- ^ Broun, "Dunkeld", Broun, "National Identity", Forsyth, "Scotland to 1100", pp. 28–32, Woolf, "Constantine II"; cf. Bannerman, "Scottish Takeover", passim, representing the "traditional" view.

- ^ For example, Pechs, and perhaps Pixies. However, Sally Foster quotes John Toland in 1726: "they are apt all over Scotland to make everything Pictish whose origin they do not know." The same could be said of the Picts in myth.

- ^ Broun, "Kingship", for Ireland see, e.g. Byrne, Irish Kings and High-Kings, and more generally Ó Cróinín, Early Medieval Ireland.

- ^ Forsyth, "Lost Pictish Source", Watson, Celtic Place Names, pp. 108–109.

- ^ Bruford, "What happened to the Caledonians", Watson, Celtic Place Names, pp. 108–113.

- ^ Woolf, "Dun Nechtain"; Yorke, Conversion, p. 47. Compare earlier works such as Foster, Picts, Gaels and Scots, p. 33.

- ^ Adomnán, "Life of Columba", editor's notes on pp. 342–343.

- ^ Broun, "Seven Kingdoms".

- ^ Woolf, "Dun Nechtain".

- ^ Bede, I, c. 1

- ^ Clancy, "Nechtan".

- ^ Byrne, Irish Kings and High-Kings, pp. 35–41 & pp. 122–123, also p. 108 & p. 287, stating that derbfhine was practised by the cruithni in Ireland.

- ^ Byrne, Irish Kings and High-Kings, p. 35, "Elder for kin, worth for rulership, wisdom for the church." See also Foster, Picts, Gaels and Scots, pp. 32–34, Smyth, Warlords and Holy Men, p. 67ff.

- ^ Broun, "Kingship", Broun, "Pictish Kings"; for Dál Riata, Broun, "Dál Riata", for a more positive view Sharpe, "The thriving of Dalriada"; for Northumbria, Higham, Kingdom of Northumbria, pp. 144–149.

- ^ Woolf, "Nobility".

- ^ Barrow, "Pre-Feudal Scotland", Woolf, "Nobility".

- ^ See, e.g. Campbell, Saints and Sea-kings for the Gaels of Dál Riata, Lowe, Angels, Fools and Tyrants for Britons and Anglians.

- ^ Celt is a word with many meanings, and may itself be unhelpful if overused.

- ^ Foster, Picts, Gaels and Scots, pp. 49–61. Fergus Kelly, Early Irish Farming: a study based mainly on the law-texts of the 7th and 8th centuries AD (School of Celtic Studies/DAIS, Dublin, 2000. ISBN 1-85500-180-2) provides an extensive review of farming in Ireland in the middle Pictish period.

- ^ The interior of the fort at Burghead was some 12 acres (5 hectares) in size, see Driscoll, "Burghead"; for Verlamion (later Roman Verulamium), a southern British settlement on a very much larger scale, see e.g. Pryor, Britain AD, pp. 64–70.

- ^ Dennison, "Urban settlement: medieval".

- ^ Foster, Picts, Gaels and Scots, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Trade, see Foster, Picts, Gaels and Scots, pp. 65–68; seafaring in general, e.g. Haywood, Dark Age Naval Power, Rodger, Safeguard of the Sea.

- ^ Armit, Towers In The North, chapter 7.

- ^ Crone, "Crannogs and Chronologies", PSAS, vol. 123, pp. 245–254.

- ^ Foster, Picts, Gaels and Scots, pp. 52–61.

- ^ See Clancy, "Nechtan", Foster, Picts, Gaels and Scots, p. 89.

- ^ For art in general see Foster, Picts, Gaels and Scots, pp. 26–28, Laing & Laing, p. 89ff., Ritchie, "Picto-Celtic Culture".

- ^ Forsyth, "Evidence of a lost Pictish Source", pp. 27–28.

- ^ Clancy, "'Nennian recension'", pp. 95–96, Smyth, Warlords and Holy Men, pp. 82–83.

- ^ Markus, "Conversion to Christianity".

- ^ Bede, III, 4. For the identities of Ninian/Finnian see Yorke, p. 129.

- ^ Mentioned by Foster, but more information is available from the Tarbat Discovery Programme: see under External links.

- ^ Bede, IV, cc. 21–22, Clancy, "Church institutions", Clancy, "Nechtan".

- ^ Taylor, "Iona abbots".

- ^ Clancy, "Church institutions", Markus, "Religious life".

- ^ Clancy, "Cult of Saints", Clancy, "Nechtan", Taylor, "Iona abbots"

- ^ Markus, "Religious life".

- ^ Forsyth, Language in Pictland, Price "Pictish", Taylor, "Place names", Watson, Celtic Place Names. For K.H. Jackson's views, see "The Language of the Picts" in Wainwright (ed.) The Problem of the Picts.

- ^ Jackson, "The Language of the Picts", discussed by Forsyth, Language in Pictland.

- ^ Forsyth, "Literacy in Pictland".

- ^ For place names in general, see Watson, Celtic Place Names; Nicolaisen, Scottish Place Names, pp 156–246. For shires and thanages see Barrow, "Pre-Feudal Scotland."

- ^ Watson, Celtic Place Names, pp. 225–233.

Bibliography

- Adomnán, Life of St Columba, tr. & ed. Richard Sharpe. Penguin, London, 1995. ISBN 0-14-044462-9

- Armit, Ian, Towers In The North: The Brochs Of Scotland Tempus, Stroud, 2002. ISBN 0-7524-1932-3

- Bannerman, John, "The Scottish Takeover of Pictland and the relics of Columba" in Dauvit Broun & Thomas Owen Clancy (eds.), Spes Scotorum: Hope of Scots. Saint Columba, Iona and the Scotland. T. & T. Clark, Edinburgh, 1999. ISBN 0-567-08682-8

- Barrow, G.W.S. "Pre-feudal Scotland: shires and thanes" in The Kingdom of the Scots. Edinburgh UP, Edinburgh, 2003. ISBN 0-7486-1803-1

- Broun, Dauvit, "Dál Riata" in Michael Lynch (ed.), The Oxford Companion to Scottish History. Oxford UP, Oxford, 2001. ISBN 0-19-211696-7

- Broun, Dauvit, "Dunkeld and the origin of Scottish identity" in Broun & Clancy (1999).

- Broun, Dauvit, "National identity: early medieval and the formation of Alba" in Lynch (2001).

- Broun, Dauvit, "Pictish Kings 761–839: Integration with Dál Riata or Separate Development" in Sally M. Foster (ed.), The St Andrews Sarcophagus: A Pictish masterpiece and its international connections. Four Courts, Dublin, 1998. ISBN 1-85182-414-6

- Broun, Dauvit, "The Seven Kingdoms in De situ Albanie: A Record of Pictish political geography or imaginary map of ancient Alba" in E.J. Cowan & R. Andrew McDonald (eds.), Alba: Celtic Scotland in the Medieval Era. John Donald, Edinburgh, 2005. ISBN 0-85976-608-X

- Bruford, Alan, "What happened to the Caledonians ?" in Cowan & McDonald (2005).

- Byrne, Francis John, Irish Kings and High-Kings. Batsford, London, 1973. ISBN 0-7134-5882-8

- Campbell, Ewan, Saints and Sea-kings: The First Kingdom of the Scots. Canongate, Edinburgh, 1999. ISBN 0-86241-874-7

- Clancy, Thomas Owen, "Church institutions: early medieval" in Lynch (2001).

- Clancy, Thomas Owen, "Ireland: to 1100" in Lynch (2001).

- Clancy, Thomas Owen, "Nechtan son of Derile" in Lynch (2001).

- Clancy, Thomas Owen, "Scotland, the 'Nennian' Recension of the Historia Brittonum and the Libor Bretnach in Simon Taylor (ed.), Kings, clerics and chronicles in Scotland 500–1297. Fourt Courts, Dublin, 2000. ISBN 1-85182-516-9

- Clancy, Thomas Owen, "Columba, Adomnán and the Cult of Saints in Scotland" in Broun & Clancy (1999).

- Cowan, E.J., "Economy: to 1100" in Lynch (2001).

- Cowan, E.J., "The Invention of Celtic Scotland" in Cowan & McDonald (2005).

- Crone, B.A., "Crannogs and Chronologies", PSAS, vol. 123 (1993), pp. 245–254.

- Cummins, W.A., The Age of the Picts. Sutton, Stroud, 1998. ISBN 0-7509-1608-7

- Dennison, Patricia, "Urban settlement: to 1750" in Lynch (2001).

- Driscoll, Stephen T., "Burghead" in Lynch (2001).

- Dyer, Christopher, Making a Living in the Middle Ages: The People of Britain 850–1520. Penguin, London, 2003. ISBN 0-14-025951-1

- Forsyth, Katherine, Language in Pictland : the case against 'non-Indo-European Pictish' (Studia Hameliana no. 2). De Keltische Draak, Utrecht, 1997. ISBN 90-802785-5-6

- Forsyth, Katherine, "Literacy in Pictland" in Huw Pryce (ed.), Literacy in Medieval Celtic Societies. Cambridge UP, Cambridge, 1998.

- Forsyth, Katherine, "Evidence of a lost Pictish Source in the Historia Regum Anglorum of Symeon of Durham", with an appendix by John T. Koch, in Taylor (2000).

- Forsyth, Katherine, "Picts" in Lynch (2001).

- Forsyth, Katherine, "Origins: Scotland to 1100" in Jenny Wormald (ed.), Scotland: A History, Oxford UP, Oxford, 2005. ISBN 0-19-820615-1

- Foster, Sally M., Picts, Gaels, and Scots: Early Historic Scotland. Batsford, London, 2004. ISBN 0-7134-8874-3

- Geary, Patrick J., Before France and Germany: The creation and transformation of the Merovingian World. Oxford U.P., Oxford, 1988. 0-19-504457-6

- Hanson, W., "North England and southern Scotland: Roman occupation" in Lynch (2001).

- Haywood, John, Dark Age Naval Power. Anglo-Saxon Books, Hockwold-cum-Wilton, 1999. ISBN 1-898281-22-X

- Henderson, Isabel, "Primus inter pares: the St Andrews Sarcophagus and Pictish Sculpture" in Foster (1999).

- Higham, N.J., The Kingdom of Northumbria AD 350–1100. Sutton, Stroud, 1993. ISBN 0-86299-730-5

- Jackson, Kenneth H., "The Pictish Language" in F.T. Wainwright (ed.), The Problem of the Picts. Nelson, Edinburgh, 1955. Reprinted Melven Press, Perth, 1980. ISBN 0-906664-07-1

- Laing, Lloyd & Jenny Lloyd, The Picts and the Scots. Sutton, Stroud, 2001. ISBN 0-7509-2873-5

- Lowe, Chris, Angels, Fools and Tyrants: Britons and Angles in Southern Scotland. Canongate, Edinburgh, 1999. ISBN 0-86241-875-5

- Markus, Fr. Gilbert, O.P., "Religious life: early medieval" in Lynch (2001).

- Markus, Fr. Gilbert, O.P., "Conversion to Christianity" in Lynch (2001).

- Nicolaisen, W.F.H., Scottish Place-Names. John Donald, Edinburgh, 2001. ISBN 0-85976-556-3

- Ó Cróinín, Dáibhí, Early Medieval Ireland: 400–1200. Longman, London, 1995. ISBN 0-582-01565-0

- Oram, Richard, "Rural society: medieval" in Lynch (2001).

- Price, Glanville, "Pictish" in Glanville Price (ed.), Languages in Britain & Ireland. Blackwell, Oxford, 2000. ISBN 0-631-21581-6

- Pryor, Francis, Britain A.D. Harper Perennial, London, 2005.ISBN 0-00-718187-6

- Ritchie, Anna, "Culture: Picto-Celtic" in Lynch (2001).

- Rodger, N.A.M., The Safeguard of the Sea. A Naval History of Great Britain, volume one 660–1649. Harper Collins, London, 1997. ISBN 0-00-638840-X

- Sellar, W.D.H., "Gaelic laws and institutions" in Lynch (2001).

- Sharpe, Richard, "The thriving of Dalriada" in Taylor (2000).

- Smyth, Alfred P., Warlords and Holy Men: Scotland AD 80–1000. Edinburgh UP, Edinburgh, 1984. ISBN 0-7486-0100-7

- Snyder, Christopher A. (2003). The Britons. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-22260-X.

- Taylor, Simon, "Place names" in Lynch (2001).

- Taylor, Simon, "Seventh-century Iona abbots in Scottish place-names" in Broun & Clancy (1999).

- Watson, W.J. The History of the Celtic Place-names of Scotland.

- Woolf, Alex, "Dun Nechtain, Fortriu and the Geography of the Picts" in The Scottish Historical Review, Volume 85, Number 2. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2006. ISSN 0036-9241

- Woolf, Alex, "Nobility: early medieval" in Lynch (2001).

- Woolf, Alex, "Ungus (Onuist) son of Uurgust" in Lynch (2001).

- Yorke, Barbara, The Conversion of Britain: Religion, Politics and Society c.600–800. Longman, London, 2006. ISBN 0-582-77292-3

Further reading

Foster (2004) is considerably revised from the 1996 edition, and offers one of the most complete introductions to the subject.

Henderson (1967) is still regarded as important. The articles in

Lynch (2001) will be useful, but this is not referenced and may be best read in conjunction with another work.

Laing & Laing (2001) provides good coverage of Pictish art, but is not well illustrated and otherwise outdated; the most thorough and by far the most up-to-date work on Pictish art is Isabel Henderson's The Art of the Picts: Sculpture and Metalwork in Early Medieval Scotland (2004).

Cummins (1999) attempts a narrative, with mixed success, and all works by Cummins should be read with caution. Smyth (1984) is widely cited, but is unlikely to be suitable reading for a beginner.

Leslie Alcock (2003) provides comprehensive coverage of Dark Age northern Britain from an archaeologist's perspective.

Marjorie Anderson (1973; 1980) provides the landmark and most authoritative guide to the historical sources of the period.

The relevant works in the new Edinburgh history of Scotland - Fraser, From Caledonia to Pictland, and Woolf, From Pictland to Alba - are expected in 2007–2008.

External links

- Glasgow University ePrints server, including Katherine Forsyth's

- CELT: Corpus of Electronic Texts at University College Cork

- The Corpus of Electronic Texts includes the Annals of Ulster, Tigernach, the Four Masters and Innisfallen, the Chronicon Scotorum, the Lebor Bretnach, Genealogies, and various Saints' Lives. Most are translated into English, or translations are in progress

- The Pictish Chronicle

- Scotland Royalty

- The Chronicle of the Kings of Alba

- Annals of Clonmacnoise at Cornell

- Bede's Ecclesiastical History and its Continuation (pdf), at CCEL, translated by A.M. Sellar.

- Annales Cambriae (translated) at the Internet Medieval Sourcebook.

- Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland (PSAS) through 1999 (pdf).

- Tarbat Discovery Programme with reports on excavations at Portmahomack.

- SPNS the Scottish Place-Name Society (Comann Ainmean-Áite na h-Alba), including commentary on and extracts from Watson's The History of the Celtic Place-names of Scotland.