Common ostrich: Difference between revisions

Undid revision 260328631 by 59.89.48.190 (talk) |

|||

| Line 128: | Line 128: | ||

===Ostrich racing===<!-- This section is linked from [[Racing]] --> |

===Ostrich racing===<!-- This section is linked from [[Racing]] --> |

||

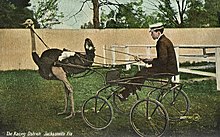

[[Image:OstrichCartJacksonville1.jpg|thumb|Ostrich pulling a cart for [[racing]].]] |

[[Image:OstrichCartJacksonville1.jpg|thumb|Ostrich pulling a cart for [[racing]].]] |

||

Ostriches are large enough for a small person to ride them, typically while holding on to the wings for grip, and in some areas of northern Africa and the [[Arabian Peninsula]] ostriches are trained as racing mounts. There is little possibility of the practice becoming more widespread, due to the irascible temperament and the difficulties encountered in saddling the birds. Ostrich races in the United States have been criticized by [[animal rights]] organizations |

Ostriches are large enough for a small person to ride them, typically while holding on to the wings for grip, and in some areas of northern Africa and the [[Arabian Peninsula]] ostriches are trained as racing mounts. There is little possibility of the practice becoming more widespread, due to the irascible temperament and the difficulties encountered in saddling the birds. Ostrich races in the United States have been criticized by [[animal rights]] organizations. |

||

===Ostrich feather dusters=== |

===Ostrich feather dusters=== |

||

Revision as of 15:06, 27 December 2008

| Ostrich | |

|---|---|

| |

| Male and Female | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | Struthionidae Vigors, 1825

|

| Genus: | Struthio Linnaeus, 1758

|

| Species: | S. camelus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Struthio camelus Linnaeus, 1758

| |

| Subspecies | |

|

see text | |

| |

| Distribution of ostriches. | |

The ostrich (Struthio camelus) is a large flightless bird native to Africa (and formerly the Middle East). It is the only living species of its family, Struthionidae, and its genus, Struthio. Ostriches share the order Struthioniformes with the Emu, kiwis, and other ratites. It is distinctive in its appearance, with a long neck and legs and the ability to run at speeds of about 74 km/h (46 mph), the top land speed of any bird.[2] The ostrich is the largest living species of bird and lays the largest egg of any bird species.

The diet of the ostrich mainly consists of plant matter, though it eats insects. It lives in nomadic groups which contain between five and 50 birds. When threatened, the ostrich will either hide itself by lying flat against the ground, or will run away. If cornered, it can cause injury and death with a kick from its powerful legs. Mating patterns differ by geographical region, but territorial males fight for a harem of two to seven females.

The ostrich is farmed around the world, particularly for its feathers, which are decorative and are also used for feather dusters. Its skin is used for leather and its meat marketed commercially.

Taxonomy

The ostrich was originally described by Linnaeus in his 18th-century work, Systema Naturae under its current binomial name.[3] Its scientific name is derived from the Greek words for "camel sparrow" alluding to its long neck.[4]

The ostrich belongs to the Struthioniformes order of ratites. Other members include rheas, emu, cassowaries and the largest bird ever, the now-extinct Elephant Bird (Aepyornis). However, the classification of the ratites as a single order has always been questioned, with the alternative classification restricting the Struthioniformes to the ostrich lineage and elevating the other groups. Presently, molecular evidence is equivocal[citation needed] while paleobiogeographical and paleontological considerations are slightly in favor of the multi-order arrangement.

Subspecies

Five subspecies are recognized:

- S. c. australis in Southern Africa, called the Southern Ostrich. It is found south of the Zambezi and Cunene rivers. It was once farmed for its feathers in the Little Karoo area of Cape Province.[5]

- S. c. camelus in North Africa, sometimes called the North African Ostrich or Red-necked Ostrich. It is the most widespread subspecies, ranging from Ethiopia and Sudan in the east throughout the Sahel to Senegal and Mauritania in the west, and at least in earlier times north to Egypt and southern Morocco, respectively. It is the largest subspecies, at 2.74 m (9 ft) 154 kilograms (340 lb).[6] The neck is red, the plumage of males is black and white, and the plumage of females is grey.[6]

- S. c. massaicus in East Africa, sometimes called the Masai Ostrich. It has some small feathers on its head, and its neck and thighs are bright orange. During the mating season, the male's neck and thighs become brighter. Their range is essentially limited to most of Kenya and Tanzania and Ethiopia and parts of Southern Somalia.[6]

- S. c. syriacus in the Middle East, sometimes called the Arabian Ostrich or Middle Eastern Ostrich, was a subspecies formerly very common in the Arabian Peninsula, Syria, and Iraq; it became extinct around 1966.

- S. c. molybdophanes in Somalia, Ethiopia, and northern Kenya, is called the Somali Ostrich. The neck and thighs are grey-blue, and during the mating season, the male's neck and thighs become bright blue. The females are more brown than those of other subspecies.[6] It generally lives in pairs or alone, rather than in flocks. Its range overlaps with S. c. massaicus in northeastern Kenya.[6]

Analyses indicate that the Somali Ostrich may be better considered a full species. mtDNA haplotype comparisons suggest that it diverged from the other ostriches not quite 4 mya due to formation of the Great Rift Valley. Subsequently, hybridization with the subspecies that evolved southwestwards of its range, S. c. massaicus, has apparently been prevented from occurring on a significant scale by ecological separation, the Somali Ostrich preferring bushland where it browses middle-height vegetation for food while the Masai Ostrich is, like the other subspecies, a grazing bird of the open savanna and miombo habitat.[7]

The population from Río de Oro was once separated as Struthio camelus spatzi because its eggshell pores were shaped like a teardrop and not round, but as there is considerable variation of this character and there were no other differences between these birds and adjacent populations of S. c. camelus, it is no longer considered valid.[8] This population disappeared in the later half of the 20th century. In addition, there have been 19th century reports of the existence of small ostriches in North Africa; these have been referred to as Levaillant's Ostrich (Struthio bidactylus) but remain a hypothetical form not supported by material evidence.[9] Given the persistence of savanna wildlife in a few mountainous regions of the Sahara (such as the Tagant Plateau and the Ennedi Plateau), it is not at all unlikely that ostriches too were able to persist in some numbers until recent times after the drying-up of the Sahara.

Evolution

The earliest fossil of ostrich-like birds is the Central European Palaeotis from the Middle Eocene, a middle-sized flightless bird that was originally believed to be a bustard. Apart from this enigmatic bird, the fossil record of the ostriches continues with several species of the modern genus Struthio which are known from the Early Miocene onwards. While the relationship of the African species is comparatively straightforward, a large number of Asian species of ostrich have been described from very fragmentary remains, and their interrelationships and how they relate to the African ostriches is very confusing. In China, ostriches are known to have become extinct only around or even after the end of the last ice age; images of ostriches have been found there on prehistoric pottery and as petroglyphs. There are also records of ostriches being sighted out at sea in the Indian Ocean and when discovered on the island of Madagascar the sailors of the 18th century referred to them as Sea Ostriches, although this has never been confirmed.

Several of these fossil forms are ichnotaxa (that is, classified according to the organism's footprints or other trace rather than its body) and their association with those described from distinctive bones is contentious and in need of revision pending more good material.[10]

- Struthio coppensi (Early Miocene of Elizabethfeld, Namibia)

- Struthio linxiaensis (Liushu Late Miocene of Yangwapuzijifang, China)

- Struthio orlovi (Late Miocene of Moldavia)

- Struthio karingarabensis (Late Miocene - Early Pliocene of SW and CE Africa) - oospecies(?)

- Struthio kakesiensis (Laetolil Early Pliocene of Laetoli, Tanzania) - oospecies

- Struthio wimani (Early Pliocene of China and Mongolia)

- Struthio daberasensis (Early - Middle Pliocene of Namibia) - oospecies

- Struthio brachydactylus (Pliocene of Ukraine)

- Struthio chersonensis (Pliocene of SE Europe to WC Asia) - oospecies

- Asian Ostrich, Struthio asiaticus (Early Pliocene - Late Pleistocene of Central Asia to China ?and Morocco)

- Struthio dmanisensis (Late Pliocene/Early Pleistocene of Dmanisi, Georgia)

- Struthio oldawayi (Early Pleistocene of Tanzania) - probably subspecies of S. camelus

- Struthio anderssoni - oospecies(?)

Description

Ostriches usually weigh from 93 to 130 kg (200 to 285 lb),[11] although some male ostriches have been recorded with weights of up to 155 kg (340 lb). The feathers of adult males are mostly black, with white at the ends of the wings and in the tail. Females and young males are greyish-brown and white. The head and neck of both male and female ostriches is nearly bare, but has a thin layer of down.[11]

The strong legs of the ostrich lack feathers. The bird has just two toes on each foot (most birds have four), with the nail of the larger, inner one resembling a hoof. The outer toe lacks a nail.[12] This is an adaptation unique to ostriches that appears to aid in running. The wings are not used for flight, but are still large, with a wingspan of around two metres (over six feet),[13] despite the absence of long flight feathers. The wings are used in mating displays, and they can also provide shade for chicks. The feathers, which are soft and fluffy, serve as insulation, and are quite different from the flat smooth outer feathers of flying birds (the feather barbs lack the tiny hooks which lock them together in other birds). The ostrich's sternum is flat, lacking the keel to which wing muscles attach in flying birds.[14] The beak is flat and broad, with a rounded tip.[11] Like all ratites, the ostrich has no crop,[15] and it also lacks a gallbladder.[16]

At sexual maturity (two to four years old), male ostriches can be between 1.8 and 2.7 m (6 to 9 ft) in height, while female ostriches range from 1.7 to 2 m (5.5 to 6.5 ft). During the first year of life, chicks grow about 25 cm (10 in) per month. At one year of age, ostriches weigh around 45 kg (100 lb). An ostrich can live up to 75 years.

Distribution and habitat

Ostriches are native to savannas and the Sahel of Africa, both north and south of the equatorial forest zone.[13] The Arabian Ostriches in the Near and Middle East were hunted to extinction by the middle of the 20th century.

Behavior

Ostriches live in nomadic groups of five to 50 birds (led by a top hen) that often travel together with other grazing animals, such as zebras or antelopes.[13] They mainly feed on seeds and other plant matter; occasionally they also eat insects such as locusts. Lacking teeth, they swallow pebbles that help as gastroliths to grind the swallowed food in the gizzard. An adult ostrich typically carries about 1 kg of stones in its stomach. Ostriches can go without water for several days, living off the moisture in the ingested plants.[17] However, they enjoy water and frequently take baths where it is available.[13]

With their acute eyesight and hearing, ostriches can sense predators such as lions from far away. When being pursued by a predator, they have been known to reach speeds in excess of 65 km/h (40 mph), and can maintain a steady speed of 50 km/h (30 mph), which makes the ostrich the world's fastest two-legged animal.[18]

Ostriches are known to eat almost anything (dietary indiscretion), particularly in captivity where opportunity is increased.

Ostriches can tolerate a wide range of temperatures. In much of its habitat, temperature differences of 40°C between night- and daytime can be encountered. Their temperature control mechanism is more complex than in other birds and mammals, utilizing the naked skin of the upper legs and flanks which can be covered by the wing feathers or bared according to whether the bird wants to retain or lose body heat.

When lying down and hiding from predators, the birds lay their heads and necks flat on the ground, making them appear as a mound of earth from a distance. This even works for the males, as they hold their wings and tail low so that the heat haze of the hot, dry air that often occurs in their habitat aids in making them appear as a nondescript dark lump. Contrary to popular belief, ostriches do not bury their heads in the sand.[19] When threatened, ostriches run away, but they can cause serious injury and death with kicks from their powerful legs.[13] Their legs can only kick forward.[20]

Reproduction

Ostriches become sexually mature when they are 2 to 4 years old; females mature about six months earlier than males. The species is iteroparous, with the mating season beginning in March or April and ending sometime before September. The mating process differs in different geographical regions. Territorial males will typically use hisses and other sounds to fight for a harem of two to seven females (which are called hens).[11] The winner of these fights will breed with all the females in an area, but will only form a pair bond with the dominant female. The female crouches on the ground and is mounted from behind by the male.

Ostriches are oviparous. The females will lay their fertilized eggs in a single communal nest, a simple pit, 30 to 60 cm (12-24 in) deep, scraped in the ground by the male. Ostrich eggs are the largest of all eggs (and by extension, the yolk is the largest single cell[citation needed]), though they are actually the smallest eggs relative to the size of the bird[citation needed]. The nest may contain 15 to 60 eggs, which are, on average, 15 cm (6 in) long, 13 cm (5 in) wide, and weigh 1.4 kg (3 lb). They are glossy and cream in color, with thick shells marked by small pits.[14] The eggs are incubated by the females by day and by the male by night.[21] This uses the coloration of the two sexes to escape detection of the nest, as the drab female blends in with the sand, while the black male is nearly undetectable in the night.[14] The incubation period is 35 to 45 days. Typically, the male will defend the hatchlings, and teach them how and on what to feed.

The life span of an ostrich is from 30 to 70 years, with 50 being typical.

Ostriches reared entirely by humans may not learn to direct their courtship behaviour at other ostriches, but instead may do so at their human keepers.[22]

Ostriches and people

Hunting and farming

In Roman times, there was a demand for ostriches to use in venatio games or cooking. They have been hunted and farmed for their feathers, which at various times in history have been very popular for ornamentation in fashionable clothing (such as hats during the 19th century). Their skins were also valued to make goods out of leather. In the 18th century, they were almost hunted to extinction; farming for feathers began in the 19th century. The market for feathers collapsed after World War I, but commercial farming for feathers and later for skins, became widespread during the 1970s.

Ostriches are farmed in over 50 countries, including climates as cold as that of Sweden and Finland, though the majority are in Southern Africa. They will prosper in climates between 30 and −30 °C[citation needed].

Since they also have the best feed to weight gain ratio of any land animal in the world (3.5:1 whereas that of cattle is 6:1)[citation needed], they are attractive economically to raise for meat or other uses. Although they are farmed primarily for leather and secondarily for meat, additional by-products are the eggs, offal, and feathers. Ostrich eggs can be used in a similar fashion to chicken eggs, with the average size ratio being 16 chicken eggs:1 ostrich egg.

It is claimed that ostriches produce the strongest commercially available leather.[23] Ostrich meat tastes similar to lean beef and is low in fat and cholesterol, as well as high in calcium, protein and iron.[24] Uncooked, it is a dark red or cherry red color, a little darker than beef.[24]

The town of Oudtshoorn in South Africa has the world's largest population of ostriches. Farms and specialized breeding centres have been set up around the town such as the Safari Show Farm and the Highgate Ostrich Show Farm. The CP Nel Museum is a museum that specializes in the history of the ostrich.

Ostrich racing

Ostriches are large enough for a small person to ride them, typically while holding on to the wings for grip, and in some areas of northern Africa and the Arabian Peninsula ostriches are trained as racing mounts. There is little possibility of the practice becoming more widespread, due to the irascible temperament and the difficulties encountered in saddling the birds. Ostrich races in the United States have been criticized by animal rights organizations.

Ostrich feather dusters

The original South African ostrich feather dusters were invented in Johannesburg, South Africa by missionary and broom factory manager Harry S. Beckner in 1903.[citation needed]

Ostrich feather dusters were wound on broom handles using a foot powered kick winder and the same wire used to attach broom straw, then sorted for quality, color and length before being wound in three layers to the handle. The first layer was wound with the feathers curving inward to hide the head of the handle. The second two layers were wound curving outward to give it a full figure and its trademark flower shape.

The first ostrich feather duster company in the United States was formed in 1913 by Harry S. Beckner and his brother George Beckner in Athol, Massachusetts, and has survived till this day as the Beckner Feather Duster Company under the care of George Beckner's great granddaughter, Margret Fish Rempher. Today the largest manufacturer of ostrich feather dusters is Texas Feathers (TxF) in Arlington, Texas.[citation needed]

Apprentices still use the manual kick winder to learn the trade of building the hand crafted ostrich feather duster. However, to speed up the manufacturing process, factories now allow craftsmen to use electric powered winders to build the duster.

The ostrich feather is durable, soft and flexible, which accounts for the success of the ostrich feather duster over the last 100 years. Because the feather does not zipper together it is prone to developing a static charge which actually attracts and holds dust which can then be shaken out or washed off. Because of its similar makeup to human hair, care of the ostrich feather requires only an occasional shampoo and towel or air dry.

The farming of ostriches for their feathers does not harm the bird. During molting season the birds are gathered in a pen, burlap sacks are placed over their heads so they will remain calm and trained pickers pluck the loose molting feathers from the birds. The birds are then released unharmed back onto the farm.[citation needed]

Footnotes

- ^ BirdLife International (2004)

- ^ Doherty (1974)

- ^ Linnaeus (1758)

- ^ Harper (2001)

- ^ Scott (2006)

- ^ a b c d e Roots (2006)

- ^ Freitag & Robinson (1993)

- ^ Bezuidenhout (1999)

- ^ Fuller, (2000)

- ^ Bibi et al. (2006)

- ^ a b c d Gilman (1903)

- ^ Fleming (1822)

- ^ a b c d e Donegan (2002)

- ^ a b c Nell (2003)

- ^ Bels (2006)

- ^ Marshall (1960)

- ^ Maclean(1996)

- ^ Mountain View Conservation and Breding Centre

- ^ The Canadian Museum of Nature, Ostrich, Struthio camelus

- ^ Halcombe (1872)

- ^ Gilman

- ^ "Ostriches "flirt with farmers"". BBC. 2003-09-05. Retrieved 2007-05-16.

Confused ostriches raised on farms are falling for their keepers, according to a researcher!

- ^ Best (2003)

- ^ a b Clark

References

- Bezuidenhout, Cornelius Carlos (1999) Studies of the population structure and genetic diversity of domesticated and ‘wild’ ostriches (Struthio camelus). PhD thesis .

- Bels, Vincent L. (2006). Feeding in Domestic Vertebrates: From Structure to Behaviour. CABI Publishing, 136. ISBN 1845930630.

- Best, Brendan (2003). Ostrich Facts. The New Zealand Ostrich Association. Downloaded 2007-10-17.

- Bibi, Faysal; Shabel, Alan B.; Kraatz, Brian P. & Stidham, Thomas A. (2006): New Fossil Ratite (Aves: Palaeognathae) Eggshell. Discoveries from the Late Miocene Baynunah Formation of the United Arab Emirates, Arabian Peninsula. Palaeontologia Electronica 9 (1): 2A. PDF fulltext

- Template:IUCN2008 Database entry includes justification for why this species is of least concern

- Clark, Bob. Ostrich Meat: Cooking Tips Canadian Ostrich Association. Downloaded 2007-10-17.

- Cooper, JC (1992). Symbolic and Mythological Animals. Aquarian Press, 170-71. ISBN 1-85538-118-4.

- Doherty, James G. (1974) Natural History Magazine, March 1974. The American Museum of Natural History; The Wildlife Conservation Society.

- Donegan, K (2002). Struthio camelus. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Downloaded 2007-10-17.

- Fleming, John (1822). The Philosophy of Zoology. The University of California, 258.

- Freitag, Stefanie & Robinson, Terence J. (1993): Phylogeographic patterns in mitochondrial DNA of the ostrich (Struthio camelus). Auk 110: 614 – 622. PDF fulltext.

- Folch, A. (1992). Family Struthionidae (Ostrich). Pp. 76-83 in; del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A. & Sargatal, J. eds. Handbook of the Birds of the World, Vol 1, Ostrich to Ducks. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. ISBN 8487334091

- Fuller, Errol (2000): Extinct Birds (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press, Oxford, New York. ISBN 0-19-850837-9.

- Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T. & Colby, F. M. (1903). The New International Encyclopædia. Dodd, Mead and Company, 497.

- Halcombe, John Joseph (1872). Mission life, ed. by J.J. Halcombe. Oxford University, 304.

- Harper, Douglas (2001). Ostrich. Online Etymology Dictionary. Downloaded 2007-10-17.

- Linnaeus, C (1758). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio decima, reformata. Holmiae. (Laurentii Salvii)., 155. "S. pedibus didactylis".Template:La icon

- Maclean, Gordon Lindsay (1996). Ecophysiology of Desert Birds. Springer, 26. IBSN 3540592695

- O'Shea, Michael Vincent; Foster, Ellsworth D.& Locke, George Herbert (1918). The World Book: Organized Knowledge in Story and Picture. Hanson-Roach-Fowler, 4423.

- Marshall, Alan John (1960). Biology and Comparative Physiology of Birds. Academic Press, 446.

- Nell, Leon (2003). The Garden Route and Little Karoo. New Holland Publishers, 164. ISBN 1868728560.

- Roots, Clive (2006). Flightless Birds. Greenwood Press, 26. ISBN 0313335451.

- Scott, Thomas A. (1996). Concise Encyclopedia Biology. Walter de Gruyter, 1149. ISBN 3110106612.

- Zoological Society of San Diego (2007). Ostrich. San Diego Zoo. Downloaded 2007-10-17.

External links

- Dacho World: American Icon in Southeast Asia, Ostrich Farmer Extraordinaire

- Bird Families of the World

- Ostrich nutritional info.

- Ostrich videos on the Internet Bird Collection

- Ostrich Farming Report on the Wire Worm

- WOC 2006 - XIII World Ostrich Congress

- Honolulu Zoo page on Ostriches

- Kruger Park page on Ostriches

- South African Ostrich Business Chamber