Megatokyo: Difference between revisions

LonelyMarble (talk | contribs) Any reason not to add this image?(Talk:Megatokyo#Creative Commons friendly drawing for the article) I added it next to a paragraph describing the artwork but move to a better spot if there is one |

Dragonfiend (talk | contribs) →Reception: improve caption context |

||

| Line 130: | Line 130: | ||

==Reception== |

==Reception== |

||

[[Image:Mt-fredart-megatokyo small.png|thumb|200px| |

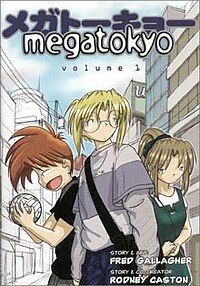

[[Image:Mt-fredart-megatokyo small.png|thumb|200px|The grayscale artwork in ''Megatokyo'' has received praise from critics in the ''The New York Times'' and elsewhere.]] |

||

The artwork and characterizations of ''Megatokyo'' have received praise from such publications as ''[[The New York Times]]''<ref name="NYT" /> and [[Comics Bulletin]].<ref name = "comicsbulletin"/> Many critics praise ''Megatokyo'' its character designs and pencil work, rendered entirely in [[grayscale]];<ref name = "Anime_News_Network"/><ref name="animatedbliss">{{cite web| title= Manga Review: ''Megatokyo'' Volume 1 | url=http://www.animatedbliss.com/REVIEWS/review.asp?TID=2342| date= February 8, 2003 |dateformat=mdy | accessdate=July 23 2006}}</ref><ref name=booklist>{{cite web | year=2005 | url=http://libraries.darkhorse.com/reviews/archive.php?theid=109 | title=''Megatokyo Volume 3'' Booklist review | dateformat=mdy | accessdate=November 7 2006 }}</ref> Conversely, however, it has also been criticized for perceived uniformity and simplicity in the designs of its peripheral characters, which have been regarded as confusing and difficult to tell apart due to their similar appearances.<ref name="flipped">{{cite web |last=Welsh | first=David | title= Comic World News | Flipped|url=http://www.comicworldnews.com/cgi-bin/index.cgi?column=flipped&page=76| dateformat= mdy |accessdate=July 19 2006}}</ref> |

The artwork and characterizations of ''Megatokyo'' have received praise from such publications as ''[[The New York Times]]''<ref name="NYT" /> and [[Comics Bulletin]].<ref name = "comicsbulletin"/> Many critics praise ''Megatokyo'' its character designs and pencil work, rendered entirely in [[grayscale]];<ref name = "Anime_News_Network"/><ref name="animatedbliss">{{cite web| title= Manga Review: ''Megatokyo'' Volume 1 | url=http://www.animatedbliss.com/REVIEWS/review.asp?TID=2342| date= February 8, 2003 |dateformat=mdy | accessdate=July 23 2006}}</ref><ref name=booklist>{{cite web | year=2005 | url=http://libraries.darkhorse.com/reviews/archive.php?theid=109 | title=''Megatokyo Volume 3'' Booklist review | dateformat=mdy | accessdate=November 7 2006 }}</ref> Conversely, however, it has also been criticized for perceived uniformity and simplicity in the designs of its peripheral characters, which have been regarded as confusing and difficult to tell apart due to their similar appearances.<ref name="flipped">{{cite web |last=Welsh | first=David | title= Comic World News | Flipped|url=http://www.comicworldnews.com/cgi-bin/index.cgi?column=flipped&page=76| dateformat= mdy |accessdate=July 19 2006}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 05:58, 13 March 2009

| Megatokyo | |

|---|---|

Megatokyo volume 1, 1st edition | |

| Author(s) | Fred Gallagher, Rodney Caston |

| Website | http://www.megatokyo.com/ |

| Current status/schedule | Monday, Wednesday, Friday (with some interruptions) |

| Launch date | August 14, 2000[1] |

| Publisher(s) | Print: CMX and Kodansha in Japan, formerly Dark Horse Comics and Studio Ironcat |

| Genre(s) | Comedy, Drama, Action, Romance |

Megatokyo is an English-language webcomic created by Fred Gallagher and Rodney Caston, debuting on August 14, 2000,[1] and then written and illustrated solely by Gallagher since July 17, 2002.[2] Gallagher's style of writing and illustrations is heavily influenced by Japanese manga. Megatokyo is freely available on its official website, with updates on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday. It is among the most popular webcomics,[3] and is currently published in book-format by CMX, although the first three volumes were published by Dark Horse. For February 2005, sales of the comic's third printed volume were ranked third on BookScan's list of graphic novels sold in bookstores, then the best showing for an original English-language manga.[4]

Set in a fictional version of Tokyo, Megatokyo portrays the adventures of Piro, a young fan of anime and manga, and his friend Largo, an American video game enthusiast. The comic often parodies and comments on the archetypes and clichés of anime, manga, dating sims, and video games, occasionally making direct references to real-world works. Megatokyo originally emphasized humor, with continuity of the story a subsidiary concern. Over time, it focused more on developing a complex plot and the personalities of its characters. This transition was due primarily to Gallagher's increasing control over the comic, which led to Caston choosing to leave the project.[5][6] Megatokyo has received praise from such sources as The New York Times,[7] while negative criticism of Gallagher's changes to the comic has been given by sources including Websnark.[8][9]

History

Megatokyo began publication as a joint project between Fred Gallagher and Rodney Caston, Internet acquaintances and, later, business partners. According to Gallagher, the comic's first two strips were drawn in reaction to Caston being "convinced that he and I could do [a webcomic] ... [and] bothering me incessantly about it", without any planning or pre-determined storyline.[10] The comic's title was derived from an Internet domain owned by Caston, which had hosted a short-lived gaming news site maintained by Caston before the comic's creation.[11] With Caston co-writing the comic's scripts and Gallagher supplying its artwork,[1] the comic's popularity quickly increased,[12] eventually reaching levels comparable to those of such popular webcomics as Penny Arcade and PvP.[3] According to Gallagher, Megatokyo's popularity was not intended, as the project was originally an experiment to help him improve his writing and illustrating skills for his future project, Warmth.[13]

In May 2002, Caston sold his ownership of the title to Gallagher, who has managed the comic on his own since then. In October of the same year, after Gallagher was laid off from his day job as an architect, he took up producing the comic as a full time profession.[14] Caston's departure from Megatokyo was not fully explained at the time. Initially, Gallagher and Caston only briefly mentioned the split, with Gallagher publicly announcing Caston's departure on June 17, 2002.[2] On January 15, 2005, Gallagher explained his view of the reasoning behind the split in response to a comment made by Scott Kurtz of PvP, in which he suggested that Gallagher had stolen ownership of Megatokyo from Caston. Calling Kurtz's claim "mean spirited", Gallagher responded:[6]

"While things were good at first, over time we found that we were not working well together creatively. There is no fault in this, it happens. I've never blamed Rodney for this creative 'falling out' nor do I blame myself. Not all creative relationships click, ours didn't in the long run."

Four days later, Caston posted his view of the development on his website:[5]

"After this he approached me and said either I would sell him my ownership of MegaTokyo or he would simply stop doing it entirely, and we'd divide up the company's assets and end it all. This was right before the MT was to go into print form, and I really wanted to see it make it into print, rather [than] die on the vine."

Production

Megatokyo is usually hand-drawn in pencil by Fred Gallagher, without any digital or physical "inking". Inking was originally planned, but dropped as Gallagher decided it was unfeasible.[15] Megatokyo's first strips were created by roughly sketching on large sheets of paper, followed by tracing, scanning, digital clean-up of the traced comics with Adobe Photoshop, and final touches in Adobe Illustrator to achieve a finished product.[16] Gallagher has stated that tracing was necessary because his sketches were not neat enough to use before tracing.[17] Because of the tracing necessary, these comics regularly took six to eight hours to complete.[17] As the comic progressed, Gallagher became able to draw "cleaner" comics without rough lines and tracing lines, and was able to abandon the tracing step.[18] Gallagher believes "that this eventually led to better looking and more expressive comics".[18]

Megatokyo's early strips were laid out in four square panels per strip, in a two-by-two square array — a formatting choice made as a compromise between the horizontal layout of American comic strips and the vertical layout of Japanese comic strips.[19] The limitations of this format became apparent during the first year of Megatokyo's publication, and in the spring of 2001, the comic switched to a manga-style, free-form panel layout. This format allowed for both large, detailed drawings and small, abstract progressions, as based on the needs of the script.[20] Gallagher has commented that his drawing speed had increased since the comic's beginning, and with four panel comics taking much less time to produce, it "made sense in some sort of twisted, masochistic way, that [he] could use that extra time to draw more for each comic".[21]

Megatokyo's earliest strips were drawn entirely on single sheets of paper.[22] Following these, Gallagher began drawing the comic's panels separately and assembling them in Adobe Illustrator, allowing him to draw more detailed frames.[22] This changed during Megatokyo's eighth chapter, with Gallagher returning to drawing entire comics on single sheets of paper.[22] Gallagher has stated that this change allows for more differentiated layouts,[23] in addition to allowing him a better sense of momentum during comic creation.[22]

The strip is currently drawn digitally as of strip number 1084.

Gallagher occasionally has guest artists participate in the production of the comic, including Mohammad F. Haque of Applegeeks.[24]

Funding

Megatokyo has had several sources of funding during its production. In its early years, it was largely funded by Gallagher and Caston's full time jobs, with the additional support of banner advertisements. A store connected to ThinkGeek was launched during October 2000 in order to sell Megatokyo merchandise, and, in turn, help fund the comic.[25] On August 1, 2004,[26] this store was replaced by "Megagear", an independent online store created by Fred Gallagher and his wife, Sarah, to be used solely by Megatokyo, although it now also offers Applegeeks and Angerdog merchandise.

Gallagher has emphasized that Megatokyo will continue to remain on the Internet free of charge, and that releasing it in book form is simply another way for the comic to reach readers,[27] as opposed to replacing its webcomic counterpart entirely.[28] Additionally, he has stated that he is against micropayments, as he believes that word of mouth and public attention are powerful property builders, and that a "pay-per-click" system would only dampen their effectiveness. He has claimed that such systems are a superior option to direct monetary compensation, and that human nature is opposed to micropayments.[28]

Themes and structure

Much of Megatokyo's early humor consists of jokes related to the video game subculture, as well as culture-clash issues. In these early strips, the comic progressed at a pace which Gallagher has called "haphazard",[29] often interrupted by purely punchline-driven installments.[30][31][32] As Gallagher gradually gained more control over Megatokyo's production, the comic began to gain more similarities to the Japanese shōjo manga that Gallagher enjoys.[2] Following Gallagher's complete takeover of Megatokyo, the comic's thematic relation to Japanese manga continued to grow.

The comic features characteristics borrowed from anime and manga archetypes, often parodying the medium's clichés.[33][22] Examples include Junpei, a ninja who becomes Largo's apprentice; Rent-a-zillas, giant monsters based on Godzilla; the Tokyo Police Cataclysm Division, which fights the monsters with giant robots and supervises the systematic destruction and reconstruction of predesignated areas of the city; fan service;[22] a Japanese school girl, Yuki, who has also started being a magical girl in recent comics;[34] and Ping, a robot girl.[35] In addition, Dom and Ed, hitmen employed by Sega and Sony, respectively, are associated with a Japanese stereotype that all Americans are heavily armed.[36]

Characters in Megatokyo usually speak Japanese, although some speak English, or English-based l33t. Typically, when a character is speaking Japanese, it is signified by enclosing English text between angle brackets (<>).[37] Not every character speaks every language, so occasionally characters are unable to understand one another. In several scenes (such as this one), a character's speech is written entirely in rōmaji Japanese to emphasize this.

Megatokyo is divided into chapters. Chapter 0, which contains all of the comic's early phase, covers a time span in the comic of about six weeks. Each of the subsequent chapters chronicles the events of a single day. Chapter 0 was originally not given a title, although the book version retroactively dubbed it "Relax, we understand j00".[38] Chapter 0 began during August 2000,[1] with chapters 1 through 10 beginning in June 2001,[39] November 2001,[40] October 2002,[41] April 2003,[42] February 2004,[43] November 2004,[44] September 2005,[45] June 2006,[46] April 2007,[47] and July 2008,[48] respectively.

Main characters

- The authors of Megatokyo chose to use "Surname–Given Name" order for characters of Japanese origin. The same format has been maintained here so as to avoid any confusion regarding these characters.

Piro

Piro, the main protagonist, is an author surrogate of Fred Gallagher. Gallagher has stated that Piro is an idealized version of himself when he was in college.[49] As a character, he is socially inept and frequently depressed. His design was originally conceived as a visual parody of the character Ruri Hoshino, from the Martian Successor Nadesico anime series.[50] His name is derived from Gallagher's online nickname, which was in turn taken from Makoto Sawatari's cat in the Japanese visual novel Kanon.[51]

In the story, Piro has extreme difficulty understanding Megatokyo's female characters, making him for the most part ignorant of the feelings that the character Nanasawa Kimiko has for him, though he has become much more aware of her attraction. Gallagher has commented that Piro is the focal point of emotional damage, while his friend, Largo, takes the physical damage in this comic.[52]

Largo

Largo is the comic's secondary protagonist, and the comic version of co-creator Rodney Caston. As the comic's primary source of humor, he is an impulsive alcoholic who speaks L33t fluently and frequently. A technically gifted character, he is obsessed with altering devices, often with hazardous results. Gallagher designed Largo to be the major recipient of the comic's physical damage.[52] Largo's name comes from Caston's online nickname.[51] Largo seems to be awkwardly blundering into a relationship with Hayasaka Erika, at the current time in the comic.

Hayasaka Erika

Hayasaka Erika (早坂 えりか) is a strong-willed, cynical, and sometimes violent character. At the time of the story, she is a former popular Japanese idol (singer) and voice actress who has been out of the spotlight for three years, though she still possesses a considerable fanbase. Erika's past relationship troubles, combined with exposure to swarms of fanboys, have caused her to adopt a negative outlook on life. Gallagher has implied that her personality was loosely based around the tsundere (tough girl) stereotype often seen in anime and manga.[53]

Nanasawa Kimiko

Nanasawa Kimiko (七澤 希美子) is a Japanese girl who works as a waitress at an Anna Miller's restaurant, and is Piro's romantic interest. The story puts forth that she is an aspiring voice actress who sometimes finds herself too shy or insecure to take on roles. Kimiko is a kind and soft-spoken character, though she is prone to mood-swings, and often causes herself embarrassment by saying things she does not mean. Gallagher has commented that Kimiko was the only female character not based entirely on anime stereotypes.[53]

Tohya Miho

Tohya Miho (凍耶 美穂, Tōya Miho) is an enigmatic and manipulative young goth girl. She is drawn to resemble a "Gothic Lolita", and is often described as "darkly cute," with Gallagher occasionally describing her as a "perkigoth."[54] Miho often acts strangely compared to the comic's other characters, and regularly accomplishes abnormal feats, such as leaping inhuman distances or perching herself atop telephone poles. Despite these displays of ability, it is hinted at that Miho has problems with her health. Little is revealed in the comic about Miho's past or motivations, although Gallagher states that these will eventually be explained. Largo believes that she (Miho) is the queen of the undead, and is the cause of the zombie invasion of Tokyo.[51] It has been hinted that she is a magical girl who may have some past connection with the zombies. As of comic 1124, she is presumed dead.

Plot

Megatokyo's story begins when Piro and Largo fly to Tokyo after an incident at the Electronic Entertainment Expo. The pair are soon stranded without enough money to buy plane tickets home, forcing them to live with Tsubasa, a Japanese friend of Piro's. When Tsubasa suddenly departs for America to seek his "first true love", the protagonists are forced out of the apartment. Tsubasa leaves Ping, a robot girl PlayStation 2 accessory, in their care.

At one point, Piro, confronted with girl troubles, visits the local bookstore to "research" -- look in the vast shelves of shoujo manga for a solution to his problem. A spunky schoolgirl, Yuki, and her friends, Asako and Mami, see him sitting amidst piles of read manga, and ask him what he is doing. Piro, flustered, runs away, accidentally leaving behind his bag.

After their eviction, Piro begins work at "Megagamers", a store specializing in anime, manga, and video games. His employer allows him and Largo to live in the apartment above the store. Largo is mistaken for the new English teacher at a local school, where he takes on the alias "Great Teacher Largo" and instructs his students in L33t, video games, and about computers. The "Tokyo Police Cataclysm Division" hires Largo after he manipulates Ping into stopping a rampaging monster, but they soon dismiss him for failing to contain a riot.

As Largo is working at the local high school, Piro encounters Yuki again while working at Megagamers, when she returns his bag and sketchbook, scribbled all over with comments about his drawings. She then, to his consternation, asks if he would give her drawing lessons. Piro, flustered, agrees, and promptly forgets about them.

Early in the story, Piro meets Nanasawa Kimiko at an Anna Miller's restaurant, where she is a waitress. Much later, Piro encounters Kimiko outside a train station, where she is worrying aloud that she will miss an audition because she has forgotten her money and railcard. Piro hands her his own railcard and walks off before she can refuse his offer. This event causes Kimiko to develop an idealized vision of her benefactor, an image which is shattered the next time they meet. Despite this, she gradually develops feelings for Piro, though she is too shy to admit them. Later on in the story, Kimiko's outburst on a radio talk show causes her to suddenly rise to idol status. Angered by the hosts' derisive comments about fanboys, she comes to the defense of her audience, immediately and unintentionally securing their obsessive adoration. Later, her new horde of fanboys find out where she works and flock to the restaurant, obsessively trying to get a picture up her skirt. Piro comes to her defense, working undercover as a busboy to get rid of all cameras. The scene eventually builds to a climax, in which Kimiko shouts at the fanboys about how she is not just a 2D girl. Piro, provoked by her outburst into defending her, threatens the fanboy crowd and collects all of their information cards. Later, going back from the restaurant, Kimiko is suffering from the aftermath of the scene and lashes out at Piro.

Meanwhile, Largo develops a relationship with Hayasaka Erika, Piro's coworker at Megagamers. As with Piro and Kimiko, Largo and Erika meet by coincidence early in the story. Later, it is revealed that Erika is a former pop idol, who disappeared from the public eye after her fiancé left her. When she is rediscovered by her fans, Largo helps thwart a fanboy horde and offers to help Erika to deal with her "vulnerabilities in the digital plane". Erika insists on protecting herself, so Largo instructs her in computer-building. This leads into a little more relationship than Largo can handle however, as he insists all computer building be done in the nude, or as close to it as possible, to avoid static electrical discharge ruining components.

The enigmatic Tohya Miho frequently meddles in the lives of the protagonists. Miho knows Piro and Largo from the "Endgames" MMORPG previous to Megatokyo's plot. She abused a hidden statistic in the game to gain control of nearly all of the game's player characters, but was ultimately defeated by Piro and Largo. In the comic, Miho becomes close friends with Ping, influencing Ping's relationship with Piro and pitting Ping against Largo in video game battles. Miho is also involved in Erika's backstory; Miho manipulated Erika's fans after Erika's disappearance. This effort ended badly, leaving Miho hospitalized, and the Tokyo Police Cataclysm Division cleaning up the aftermath. Most of the exact details of what happened are left to the readers' imagination.

After getting yelled at for retaining her waitress job, Kimiko quits her voice acting job and goes home to find Erika programming her computer in her undergarments. Not long after Erika tells Kimiko to strip, Piro comes by, who she tells to get undressed as well. While Erika and Piro talk about her, Kimiko runs out of the apartment. Kimiko runs into Ping, who wanted to talk to Piro about why, after an earthquake, she had started to cry uncontrollably. They encounter Largo at the store, who explains what went wrong, although no one knows what he means until Piro comes in and translates. Ping is relieved to know that she won't shut down and Kimiko hugs Piro and apologizes for her actions. Largo leaves for Erika's apartment after she calls looking for help. That night, while Piro and Kimiko fall asleep watching TV, Erika, who finished the computer with Largo's help, tries to seduce Largo, but it freaks him out and he runs out for home. The next morning, after Kimiko departed, Piro finds out she quit her job and tries to find her.

However, Dom tries to coerce Kimiko to join SEGA for protection from fans, but she denies, resulting in Miho rescuing her from a robot sent for Kimiko. Piro encounters a group who found her cell phone and computer after she abandoned them to escape Dom. They want to help Piro get together with Kimiko, partially due to feeling bad for trying to snap a picture up Kimiko's skirt. As Piro and the group set out for a press conference Kimiko has agreed to attend, a zombie outbreak occurs downtown, apparently under the control of Miho, who later calls them off.

Largo and Yuki, revealed to be a "magical girl", steal a Rent-a-Zilla to fight the outbreak, but Largo leaves Yuki and the Rent-a-Zilla to help Piro get to Kimiko, in the middle of her press conference. Unfortunately, the Rent-a-Zilla gets bitten by a couple of zombies and turns into one himself, going on a rampage downtown. Yuki protects the Rent-A-Zilla from the Tokyo Police Cataclysm Division and even adopts him as a pet later on, much to her father's chagrin.

A while afterwards, Piro and Kimiko have made up and Kimiko returned to both of her jobs. Ping is concerned about the whereabouts of Miho, but Piro is still upset about what happened.

Books

Megatokyo was first published in print by Studio Ironcat, a partnership announced in September 2002.[55] Following this, the first book, a compilation of Megatokyo strips under the title "Megatokyo Volume One: Chapter Zero", was released by Studio Ironcat in January of 2003.[56] According to Gallagher, Studio Ironcat was unable to meet demand for the book, due to problems the company was facing at the time.[57] On July 7, 2003, Gallagher announced that Ironcat would not continue to publish Megatokyo in book form.[58] This was followed by an announcement on August 27, 2003 that Dark Horse Comics would publish Megatokyo Volume 2 and future collected volumes, including a revised edition of Megatokyo Volume 1.[59] The comic once more changed publishers in February of 2006, moving from Dark Horse Comics to the CMX Manga imprint of DC Comics.[60]

As of May 23, 2007, five volumes are available for purchase: volumes 1 through 3 from Dark Horse and volumes 4 and 5 by CMX/DC. The books have also been translated into German, Italian, French and Polish.[13] In July 2004, Megatokyo was the tenth best-selling manga property in the United States,[61] and during the week ending February 20, 2005, volume 3 ranked third in the Nielsen BookScan figures,[4] which was not only its highest ranking to date (as of August 2006), but also made it the highest monthly rank for an original English-language manga title.[4]

- Megatokyo Volume 1: Chapter Zero (Megatokyo vol.1 1st ed.) ISBN 1-929090-30-7

- Megatokyo Volume 1, 2nd ed. ISBN 1-59307-163-9 (published March 21, 2004)[62]

- Megatokyo Volume 2 ISBN 1-59307-118-3 (published January 22, 2004)[63]

- Megatokyo Volume 3 ISBN 1-59307-305-4 (published February 2, 2005)[64]

- Megatokyo Volume 4 ISBN 1-4012-1126-7 (published June 21, 2006)[65]

- Megatokyo Volume 5 ISBN 1-4012-1127-5 (published May 23, 2007)[66]

In July 2007, Kodansha announced that in 2008 it intends to publish Megatokyo in a Japanese-language edition, (in a silver slipcased box as part of Kodansha Box editions, a new manga line started in November 2006). Depending on reader response, Kodansha hopes to subsequently publish the entire Megatokyo book series.[67] The first volume will be released in Japan in March 2009, and Kodansha has acquired the rights to publish Volume 2 as well.[citation needed]

Reception

The artwork and characterizations of Megatokyo have received praise from such publications as The New York Times[7] and Comics Bulletin.[68] Many critics praise Megatokyo its character designs and pencil work, rendered entirely in grayscale;[69][70][71] Conversely, however, it has also been criticized for perceived uniformity and simplicity in the designs of its peripheral characters, which have been regarded as confusing and difficult to tell apart due to their similar appearances.[72]

Some critics, such as Eric Burns of Websnark, have found the comic to suffer from "incredibly slow pacing" (as of March 2009[update], only about 2 months of in-universe time have elapsed[73]), unclear direction or resolutions for plot threads, a lack of official character profiles and plot summaries for the uninitiated, and an erratic update schedule.[8] Burns also harshly criticized the often uncanonical filler material Gallagher employs to prevent the comic's front page content from becoming stagnant,[8] such as Shirt Guy Dom, a punchline-driven stick figure comic strip written and illustrated by Megatokyo editor Dominic Nguyen. Following Gallagher taking on Megatokyo as a full-time occupation, some critics have complained that updates should be more frequent than when he worked on the comic part time.[8] Update schedule issues have prompted Gallagher to install an update progress bar for readers awaiting the next installment of the comic.

Megatokyo's fans have been called "some of the most patient and forgiving in the webcomic world."[29] During an interview, Gallagher stated that Megatokyo fans "always [tell] me they are patient and find that the final comics are always worth the wait,"[29] but he feels as though he "[has] a commitment to my readers and to myself to deliver the best comics I can, and to do it on schedule,"[29] finally saying that nothing would make him happier than "[getting] a better handle on the time it takes to create each page."[29] Upon missing deadlines, Gallagher often makes self-disparaging comments.[29] Poking fun at this, Jerry "Tycho" Holkins of Penny Arcade has claimed to have "gotten on famously" with Gallagher, ever since he "figured out that [Gallagher] legitimately detests himself and is not hoisting some kind of glamour."[74]

While Megatokyo was originally presented as a slapstick comedy, it began focusing more on the romantic relationships between its characters after Caston's departure from the project. As a result, some fans, preferring the comic's gag-a-day format, have claimed its quality was superior when Caston was writing it.[9] Additionally, it has been said that, without Caston's input, Largo's antics appear contrived.[8] Comics Bulletin regards Megatokyo's characters as convincingly portrayed, commenting that "the reader truly feels connected to the characters, their romantic hijinks, and their wacky misadventures with the personal touches supplied by the author."[68] Likewise, Anime News Network has praised the personal tone in which the comic is written, stating that much of its appeal is a result of the "friendly and casual feeling of a fan-made production."[69]

Gallagher states early in Megatokyo Volume 1 that he and Caston "didn't want the humor ... to rely too heavily on what might be considered 'obscure knowledge.'" An article in The New York Times insists that such scenarios were unavoidable, commenting that the comic "sits at the intersection of several streams of obscure knowledge," including "gaming and hacking; manga ... the boom in Web comics over the past few years; and comics themselves."[7] The article also held that "Gallagher doesn't mean to be exclusive ... he graciously offers translation of the strip's later occasional lapses into l33t ... [and] explains why the characters are occasionally dressed in knickers or as rabbits."[7] The newspaper went on to argue that "The pleasure of a story like Megatokyo comes not in its novelistic coherence, but in its loose ranginess."[7]

Megatokyo was nominated in at least one category of the Web Cartoonist's Choice Awards every year from 2001 through 2007. It won Best Comic in 2002, as well as Best Writing, Best Serial Comic, and Best Dramatic Comic. The largest number of nominations it has received in one year is 14 in 2003, when it won Outstanding Environment Design.[75]

References

- ^ a b c d "Start of Megatokyo (strip #1)". Retrieved 2005-09-03.

- ^ a b c Gallagher, Fred (June 17, 2002). "the other brick". Megatokyo. Retrieved May 19 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) Fred Gallagher's news post announcing Caston's departure. Cite error: The named reference "gallaghernews" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ a b Alexa traffic rankings for Megatokyo.com[1], compared to PvPOnline.com[2] and Penny-Arcade.com[3].

- ^ a b c "Megatokyo Reaches Number 3". March 4, 2005. Retrieved April 14 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ a b Caston, Rodney (January 18, 2005). "The truth about Megatokyo?". Retrieved July 2 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help)Rodney Caston's version of the events surrounding his departure - ^ a b Gallagher, Fred (January 15, 2005). "more largos??". Megatokyo. Retrieved August 26 2005.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) Fred Gallagher's view of Rodney Caston's departure. - ^ a b c d e Hodgman, John (July 18, 2004). "CHRONICLE COMICS; No More Wascally Wabbits". The New York Times. Retrieved April 11 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e Burns, Eric (August 22, 2004). "You Had Me, And You Lost Me: Why I don't read Megatokyo". Websnark. Retrieved August 27 2005.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ a b Sanderson, Brandon (June 18, 2004). "The Official Time-Waster's Guide v3.0". Retrieved July 19 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ Megatokyo book one, pg. 6

- ^ Weiser, Kevin (September 27, 2001). "20 Questions with Megatokyo". Archived from the original on 2003-07-28. Retrieved August 19 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) Interview with Fred Gallagher and Rodney Caston accessed through archive.org - ^ Reid, Calvin (February 24, 2003). "American Manga Breaks Out". Publishers Weekly. Retrieved July 23 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ a b Gallagher, Fred (January 2, 2006). "comiket dreamin'". Megatokyo. Retrieved June 17 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) Fred Gallagher comments on Megatokyo's originally experimental status, and mentions that the Megatokyo books have been translated into German, Italian, French and Polish. Cite error: The named reference "popularity/languages" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Gallagher, Fred (October 30, 2002). "full time jitters". Megatokyo. Retrieved August 16 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help)A news post by Fred Gallagher in which he mentions that he has been laid off from work, and announces that he is now working on Megatokyo full-time. - ^ Megatokyo book one, pg. 11

- ^ Megatokyo book one, pg. 148

- ^ a b Megatokyo book one, pg. 18

- ^ a b Megatokyo book one, pg. 42

- ^ "Fred Gallagher and Rodney Caston's reasoning for the square panel layout". Megatokyo. April 18, 2001. Retrieved May 21 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ Gallagher, Fred (April 23, 2001). "1:1.5". Megatokyo. Retrieved May 9 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) Fred Gallagher details the change of panel layout. - ^ Megatokyo book one, pg. 105

- ^ a b c d e f Gallagher, Fred (October 3, 2006). "full page, part 2". Retrieved November 3 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ Gallagher, Fred (October 1, 2006). "full page". Retrieved November 3 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ http://www.megatokyo.com/index.php?strip_id=1011

- ^ Gallagher, Fred (October 21, 2000). "we have t-shirts..." Megatokyo. Retrieved May 21 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) Fred Gallagher announces first Megatokyo store. - ^ Gallagher, Fred (August 1, 2004). "learning to fly". Megatokyo. Retrieved August 5 2005.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) Fred Gallagher comments about Megagear's launch status. - ^ "Megatokyo goes to Tokyo – interview with Fred Gallagher". April 26, 2004. Retrieved June 4 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ a b Curzon, Joe (January 28, 2004). "Interview with Fred Gallagher". Archived from the original on 2004-08-13. Retrieved June 4 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) Cite error: The named reference "fredinterview" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ a b c d e f "Take a Trip to Megatokyo". June 21, 2006. Retrieved August 19 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) IGN interview with Fred Gallagher. - ^ "Megatokyo Strip 45". Retrieved July 18 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ "Megatokyo Strip 51". Retrieved July 18 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ "Megatokyo Strip 85". Retrieved July 18 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ Gallagher, Fred (February 2, 2006). "common gripes". Retrieved November 3 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ Megatokyo book one, pg. 51

- ^ Megatokyo book one, pg. 156

- ^ Megatokyo book one, pg. 13

- ^ Megatokyo book one, pg. 33

- ^ Megatokyo book one, pg. 5

- ^ "Start of Megatokyo chapter one". Retrieved November 3 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ "Start of Megatokyo chapter two". Retrieved November 3 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ "Start of Megatokyo chapter three". Retrieved November 3 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ "Start of Megatokyo chapter four". Retrieved November 3 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ "Start of Megatokyo chapter five". Retrieved November 3 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ "Start of Megatokyo chapter six". Retrieved November 3 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ "Start of Megatokyo chapter seven". Retrieved November 3 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ "Start of Megatokyo chapter eight". Retrieved May 11 2007.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ "Start of Megatokyo chapter nine". Retrieved February 15 2007.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ "Start of Megatokyo chapter ten". Retrieved August 5 2008.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ Gallagher, Fred (June 8, 2006). "i'll take my art back now". Megatokyo. Retrieved June 20 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) A news post by Fred Gallagher in which he states that the character "Piro" is an idealized version of himself (Gallagher) when he was in college. - ^ "An interview with Fred Gallagher". December 18, 2002. Retrieved August 17 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ a b c "Megatokyo Panel at Akon 13". Retrieved July 5 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ a b Contino, Jennifer (September 5, 2002). "MEGATOKYO'S FRED GALLAGHER". Retrieved August 18 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help)An interview with Fred Gallagher at THE PULSE - ^ a b Gallagher, Fred (January 6, 2005). "finding kimiko". Retrieved August 18 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) Gallagher comments on Kimiko being of original design. - ^ Gallagher, Fred. Megatokyo Volume 1. Dark Horse Books, 2004. Pages 90 and 154.

- ^ "Megatokyo Press Release (8/2/2002)". Archived from the original on 2003-04-16. Retrieved June 26 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ "Megatokyo Vol 1 Chapter Zero at Amazon.com". Retrieved November 7 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ Kean, Benjamin. "Fred Gallagher On The Megatokyo Move". Retrieved June 27 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ Gallagher, Fred (July 7, 2003). "re: megatokyo book 2". Megatokyo. Retrieved June 26 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) Fred Gallagher announces that Studio Ironcat will not publish Megatokyo volumes 2 and above. - ^ Gallagher, Fred (August 27, 2003). "Megatokyo joins Dark Horse Comics". Megatokyo. Retrieved June 26 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) Fred Gallagher announces Megatokyo's move to Dark Horse Comics. - ^ "Megatokyo changes publishers to DC Comics / CMX Manga". Retrieved February 26 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ "ICv2 Looks at Manga Channel Shift". July 7, 2004. Retrieved April 14 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ "Darkhorse's product details on Volume One". Retrieved September 1 2005.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ "Darkhorse's product details on Volume Two". Retrieved September 1 2005.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ "Darkhorse's product details on Volume Three". Retrieved September 1 2005.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ "CMX Manga's product details on Volume 4". Retrieved April 9 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ "Gallagher's blog on Megatokyo.com". Retrieved April 23 2007.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ Calvin Reid (2007-07-10). "Kodansha to Publish Megatokyo in Japan – 7/10/2007 – Publishers Weekly". Publishers Weekly. Retrieved 2007-07-11.

- ^ a b Murray, Robert (June 28, 2006). "Megatokyo v4 Review". Comics Bulletin. Retrieved July 18 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ a b "Megatokyo Volume 1 Special Review". Anime News Network. February 8, 2003.

- ^ "Manga Review: Megatokyo Volume 1". February 8, 2003. Retrieved July 23 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ "Megatokyo Volume 3 Booklist review". 2005. Retrieved November 7 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ Welsh, David. "Comic World News". Retrieved July 19 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Text "Flipped" ignored (help) - ^ http://www.megatokyo.com/faq

- ^ Holkins, Jerry (March 27, 2006). "The Doujinshi Code". Penny Arcade. Retrieved April 11 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ "Web Cartoonist's Choice Awards (official site)".

External links

| Fan translations |

|---|

- The Megatokyo website

- RSS http://www.megatokyo.com/rss/megatokyo.xml Megatokyo news

- The Megatokyo Forums

- Dark Horse Comics, previous book publisher of Megatokyo.

- DC Comics imprint, CMX Manga, current book publisher of Megatokyo.

- Fredart, other art by Fred Gallagher.

- Rcaston.com, blog of Rodney Caston.

- Megatokyo article at Comixpedia, a webcomic wiki

- Megatokyo discussion on Webcomicsreview.com

Fan sites

- Wikitokyo, an unofficial wiki dedicated to information about Megatokyo

- Reader's Guide to MegaTokyo, lots of information on Megatokyo plot and characters