Battle of the Trebia: Difference between revisions

Botteville (talk | contribs) |

|||

| Line 47: | Line 47: | ||

===Capture of Clastidium=== |

===Capture of Clastidium=== |

||

Despite Gallic willingness to supply Hannibal, he found that the size of his army was becoming a burden on the local communities resulting in a "daily increasing scarcity." The Romans had a grain storage depot at [[Clastidium]] (now Casteggia), which he was planning to attack. He must have bypassed it previously on his way to Piacenza. Instead |

Despite Gallic willingness to supply Hannibal, he found that the size of his army was becoming a burden on the local communities resulting in a "daily increasing scarcity." The Romans had a grain storage depot at [[Clastidium]] (now Casteggia), which he was planning to attack. He must have bypassed it previously on his way to Piacenza. Instead of attacking, he found that he could bribe the commander, Dasius Brundisius, whose name indicates he was not Roman but was from [[Brundisium]], with 400 gold coins.<ref>Livy XXI.48.</ref> The garrison was subsequently treated with kindness, which suggests that good treatment was part of the deal, but none of the sources describe it in detail. |

||

Castidium was located on the left bank on the Po upstream from the Trebbia. That Hannibal could operate there without hinderance indicates that he was in fact camped on the left bank of the Trebbia and subsequent operations against the Gauls there prove it even further. |

Castidium was located on the left bank on the Po upstream from the Trebbia. That Hannibal could operate there without hinderance indicates that he was in fact camped on the left bank of the Trebbia and subsequent operations against the Gauls there prove it even further. |

||

Revision as of 08:23, 19 March 2009

| Battle of the Trebia | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Second Punic War | |||||||

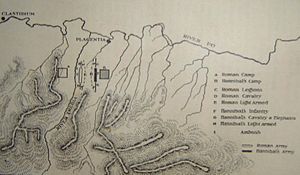

This map of the battlefield supports J. Wells' 1926 view that the Romans camped on the left bank and crossed to the right. This article adopts Mommsen's classic view that the Romans camped on the right bank and crossed to the left. The left-to-right theory leaves Tiberius' men no way to fall back across the Trebbia on Piacenza, which both sources say they did. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Carthage | Roman Republic | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Hannibal | Tiberius Sempronius Longus | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

20,000 infantry 10,000 cavalry, 37 elephants |

16,000 infantry 4,000 cavalry, 20,000 Italic auxiliaries | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Approximately 26000-28000, roughly 75%, mainly new recruits of Tiberius. | |||||||

The Battle of the Trebia (or Trebbia) was the first major battle of the Second Punic War, fought between the Carthaginian forces of Hannibal and the Roman Republic in December of 218 BC, on or around the winter solstice. The battle took place in the flat country of the Province of Piacenza on the left bank of the Trebbia River, a shallow, braided stream, not far south from its confluence (from the south) with the Po river. The battle is named for the river. Although the precise location is not known for certain it is generally accepted as being visible from the Via Emilia, now paralleled by highway A21/E70 and a railroad trunk line, all of which come from Piacenza, an ancient Etruscan city targeted contemporaneously for Roman colonization, and cross the river north of where the Romans did in the battle. The area is in the comune of Rottofreno at its main settlement, San Nicolò a Trebbia, at the coordinates given at the head of this article.

Sources and problems

The two main sources on the battle are the History of Rome by Livy (Book XXI) and Histories of Polybius (Book III). The two vary considerably in some of the geographical details and are ambiguous about some key points, especially whether the Romans were camped on the left bank or the right bank of the Trebbia and in which direction they crossed the river. Reconstruction of the disposition is the major scholarly concern regarding the battle. The sources all agree on the outcome.

Contending views stem from the confusion of real and hypothetical events, beginning with the supposed "union" of the two consular armies, which Tiberius had been ordered to effect. He was advancing "with all speed to join Publius."[1] The supposed union amounted only to Tiberius having "many close conferences with Scipio, ascertaining the truth about what had occurred, and discussing the present situation with him."

Whether the union went any further is questionable. The two consuls maintained widely separated camps. Polybius assumes a union of troops would have been effected and Tiberius would be commanding four legions (he uses conditional language and not declarative statements). He explains how after the defeat Tiberius' army fell back on Piacenza but neglects totally to say what happened to the wounded Scipio and how he got to Piacenza. Livy on the other hand although repeating Polybius' numbers states that after the battle Scipio quietly marched his army into Piancenza and went on to Cremona so that there would not be two armies wintering in Piacenza.

If Scipio's army was intact and quietly marched into Piacenza it is unlikely that either consul commanded any of the troops of the other nor did they assist one another in any way; in fact, there is no evidence that Tiberius informed Scipio he was going to attack. He is reported to have asked Scipio his advice on whether to attack and was strongly advised against it. There is no account at all of Scipio handing over any troops. If, as many authors suppose, Hannibal was trying to prevent a union, he seems singularly unaware of it. He made no move to stop Tiberius coming up from the east. The consuls themselves, however, each jealously guarded his own authority.

Starting with Polybius some military writers throughout the centuries have assumed that because union was intended it was effected, which assumption leads to the problem of "the Roman Camp." There were not one, but two, Scipio's in the hills on the left bank and Tiberius' in the plains on the right bank. Neglect of this duality leaves the writers free to select either (or neither) as "the Roman Camp;" consequently, it appears now on the left bank, now on the right; now in the hills and now on the plain.

Hannibal's perception of the non-union led him to the winning strategy. Provoking Tiberius to send his men wading through the chilled winter waters of the Trebbia during a precipitation of snow and rain he attacked the Romans from ambush with his own rested, fed and warm men and killed 2/3 to 3/4 of them, driving the lucky ones back across the river to Piacenza. The Romans it is said could scarcely lift their arms to defend themselves.

Prelude

The arrival of Hannibal

Hannibal began the Second Punic War in 219 BC by attacking the Roman-allied city of Saguntum just north of what is now Valencia in Spain. After destroying the city, he marched on Italy, beginning with a force of approximately 102000 men and a few dozen war elephants when he crossed the Ebro river in Spain, the previous border between Roman and Carthaginian interests. Trekking over the Alps the Carthaginian force made it through the mountains with staggering losses, being reduced to 26000 emaciated men. Winning a completely unequal conflict against the Ligurians and the first legion-sized battle with the Romans at the river Ticinus, he had filled out his army with Gallic and other allies to the number of 90000 men: 80000 infantry and 10000 cavaly, by the time of the Battle of Trebbia. They were more than enough to be completely effective against the Romans; moreover, by that time Hannibal had turned all Gallia Cisalpina (the region in which the battle was fought) against the Romans and the Carthaginians were prospering on enthusiastic Gallic supply and support.

The arrival of Sempronius Longus

The Roman Senate, appalled by the massacre of the Ligurians, had ordered the consul Tiberius Sempronius Longus, who was stationed in Sicily, to reinforce the existing Roman general, Publius Cornelius Scipio. Unknown to them now, Scipio had been wounded during the Battle of Ticinus and had been driven into the hills south of Piacenza, then Placentia, an old Etruscan city targeted for recolonization by the Romans, in view of the fact that the Gauls had taken over all north Italy, after burning Rome to the ground. The Gauls had turned against Rome now in favor of Hannibal over this very issue of colonization. Hannibal was camped in the plain below Scipio's camp, enjoying the favor of the Gauls. Piacenza was not being occupied by either army.

Receiving the orders of the Senate at Lilybaeum in Sicily, Sempronius had dismissed his men after taking their oaths to reassemble at Ariminum south of the Po river. From there he probably marched along the route of the future Via Aemilia straight into Piacenza. Sempronius' two legions assembled probably in early December. It wasn't long before "Tiberius and his legions arrived and marched through the city."[2] They did not stop there, probably because Hannibal's Numidian cavalry had burned the Roman fort, but camped outside it to the south, at or near Hannibal's previous camp, some 40 days after they had left Sicily. Apparently Hannibal had crossed the Trebbia in his pursuit of Scipio and was camped on its left bank.

Capture of Clastidium

Despite Gallic willingness to supply Hannibal, he found that the size of his army was becoming a burden on the local communities resulting in a "daily increasing scarcity." The Romans had a grain storage depot at Clastidium (now Casteggia), which he was planning to attack. He must have bypassed it previously on his way to Piacenza. Instead of attacking, he found that he could bribe the commander, Dasius Brundisius, whose name indicates he was not Roman but was from Brundisium, with 400 gold coins.[3] The garrison was subsequently treated with kindness, which suggests that good treatment was part of the deal, but none of the sources describe it in detail.

Castidium was located on the left bank on the Po upstream from the Trebbia. That Hannibal could operate there without hinderance indicates that he was in fact camped on the left bank of the Trebbia and subsequent operations against the Gauls there prove it even further.

Dissent among the Gauls

Hannibal set about luring Sempronius into a pitched battle on equal terms, before Scipio could recover from his wounds.

The consuls confer

The numbers

Romans

When Scipio left Marseille he had no or minimal forces. In north Italy he superseded Lucius Manlius, acquiring his two legions, and Gaius Atilius, reacquiring the legion that had been taken from him by the Senate plus 5000 allies. Since Livy is using 4000 infantry and 300 cavalry as the standard complement of a legion, Scipio should have had 12000 Roman infantry and 900 Roman cavalry plus indefinite numbers of allies, at least 5000. He should have had at least 18000 men. As the Senate had ordered the recruitment of 40000 allied infantry and 1800 cavalry to assist six legions, Scipio would have had several thousand more, diminished by any losses at Ticinus; that is, about 25000 men.

Sempronius had been given two legions: 8000 infantry and 600 cavalry, but he also must have had several thousand allies, about 15000 men. Scipio had the greater army and would have been senior in command if active. Neither consul, however, could supersede the other without a decree from the Senate.

Livy states the actual number of Roman troops before the battle to have been 18000 men, to which were added 20000 Latin allies.[4] Polybius sets the number at 16000 and 20000 allies, "this being the strength of their complete army for decisive operations, when the consuls chance to be united."[5] He does not say that they were united, only that, if they were, this would be their numbers; that is , 4 Roman legions and 5 allied legions.

Carthaginian

Battle

Preparation

The December of 218 BC was particularly cold and snowy. Scipio was still recovering from his wounds but Sempronius was spoiling for a fight. Eager to come to blows with Hannibal before Scipio could recover and assume command –and particularly as the time for the election of new consuls was drawing near—Sempronius took measures looking for a general engagement, disregarding Scipio's caution to beware of Hannibal.[6] Unfortunately for Sempronius, Hannibal was aware of this, and prepared a plan to take advantage of Sempronius' impetuosity. Hannibal's force was camped across the cold and swollen Trebia River.[7] He had noticed, says Polybius, a “place between the two camps, flat indeed and treeless, but well adapted for an ambuscade, as it was traversed by a water-course with steep banks, densely overgrown with brambles and other thorny plants, and here he proposed to lay a stratagem to surprise the enemy”.[8] Hannibal, having ascertained by the use of several Gallic spies the whereabouts of his opponents, which he had deemed essential, sent a chosen detachment of 1,000 light infantry and 1,000 Numidian cavalry [9] under the command of his younger brother Mago, to conceal themselves in the underbush among the streambeds along the Trebia under the cover of night, and prepare an ambush for the Romans. Then, on the following morning, he sent his cavalry beyond the Trebia to harass the nearby Roman camp and retreat, so as to lure the Romans into a position from which Mago’s hidden detachment could strike at the opportune moment.

Events

No sooner had the Carthaginian cavalrymen arrived in the vicinity of the Roman camp than Sempronius sent out his own cavalry to drive them off, and shortly afterwards recklessly sent towards battle his entire army of 36,000 Roman infantry, 4,000 allied equites auxilia (light auxiliary cavalry), and 3,000 Gallic auxiliaries. The day was raw, snow was falling, the Romans had not yet eaten their morning meal, and by the time the legions had crossed the Trebia fords the men were exceedingly tired and chilled.[7] The Carthaginians on the other hand, had fed themselves well, and anointed themselves in oil before their campfires. Hannibal now arranged his army on a field of his own choosing. He positioned 1,000 light infantry as a skirmishing line, and behind them, he placed the main battle line of 20,000 infantry of Libyan, Iberians, and Celtic mercenary infantry, with 10,000 light shock cavalry and some fifteen elephants split between the two flanks. Sempronius arranged his army in the standard Roman three-line formation, throwing out the velites (Roman skirmish infantry) to the front, and placing the cavalry on the flanks, while the Gallic warriors, who were allied to Rome, were placed on the left of the legions.

The light infantry screen first clashed, but the velites performed poorly and they were withdrawn. After the velites retired through the gaps in the Roman line, the hastati and principes (heavy-armed infantry or legionaries) took their place and engaged in a struggle with their opponents. As the opposing heavy infantry remained locked in a severe hand-to-hand struggle, the Carthaginian cavalry and elephants attacked the Roman cavalry, whom they greatly outnumbered. Gradually, the Roman cavalry wings were pushed farther and farther back, leaving their infantry, whom they intended to protect, more and more exposed.[8] Meanwhile, Hannibal had dispatched forward all his war elephants to attack the Gallic allies on the extreme Roman left, who, having never seen such creatures before, were quickly demoralized and retreated. After the Roman cavalry had been driven off the field, the Carthaginian cavalry fell savagely on the unprotected flanks of the Roman legionaries, hindering them from dealing with the enemy foot soldiers who faced them.[8] At the same time, Mago’s hidden force emerged from the ambush and fell upon the rear of the hard-pressed Roman infantry. With their morale already sapped by cold, hunger and fatigue, the Romans broke under this fresh onslaught and then finally collapsed under intense pressure.[10]

What had once been a line of determined fighting soldiers became a mob of helpless men, whose only remaining strength was in their legs. Thousands were cut down on the spot and trampled by elephants, and many more drowned attempting to cross the river to safety. Trapped in between Hannibal’s forces, the Romans were quickly routed, losing more than a third of their forces. The vanguard of Sempronius' centre had a more fortunate fate. Having been forced to advance by pressure from the rear, the Romans in the centre actually defeated the troops opposing them, and managed to break through the Carthaginian line, advancing so far that they became separated from their wings. However, seeing that both their flanks had been driven from the field, these men retreated in good order to the nearby town of Placentia. This resulted in Hannibal’s first great victory over the Romans.

Aftermath

The Romans, stunned and dismayed by Sempronius’s defeat at Trebia, immediately made plans to counter the new threat from the north. The Romans found to their cost that Hannibal would not be defeated as easily as they expected. From then on Rome's greatest fear was that Hannibal would get an army of considerable size.[11] Sempronius returned to Rome and the Roman senate resolved to elect new consuls the following year in 217 B.C. The two new consuls elected were Gnaeus Servilius Geminus and Gaius Flaminius, the latter of whom would lead the Roman army during the debacle at Lake Trasimene.

Video games

- This battle is featured in the demo of videogame Rome: Total War as well as being a historical battle in the full game itself.

- It was also the first battle in the series Time Commanders, where the team commanded the Carthaginian army and won the battle with a similar strategy to the one used by Hannibal.

References

- ^ Polybius III.68.

- ^ Polybius, Histories, Book III.68.

- ^ Livy XXI.48.

- ^ Livy XXI.55.

- ^ Polybius III.72.

- ^ Dodge, Theodore. Hannibal. Cambridge Massachusetts: De Capo Press, 1891 ISBN 0-306-81362-9

- ^ a b Mary Macgregor, The Story of Rome, retrieved on 18 December 2006

- ^ a b c Cottrell, Leonard, Enemy of Rome, Evans Bros, 1965. ISBN 0-237-44320-1 (pbk)

- ^ Invasion of Italy

- ^ Gowen, Hilary, Hannibal Barca and the Punic Wars.

- ^ G.A. Henty-book The Young Carthaginian

Bibliography

- Livy (1965). The War with Hannibal: Books XXI-XXX of the History of Rome from Its Foundation (reprint, illustrated ed.). Penguin Classics. ISBN 014044145X, 9780140441451.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Polybius (1922). The Histories. The Loeb Classical Library (in Ancient Greek and English). Vol. 2. London, New York: William Heinemann, G.P. Putnam's Sons.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link)

External links

- Battle of the Trebia

- Battle of the Trebia animated battle map by Jonathan Webb