Documentary hypothesis: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 114: | Line 114: | ||

* Kaufmann, Yehezkel, ''The Religion of Israel, from Its Beginnings to the Babylonian Exile'', University of Chicago Press, 1960. (Translated by Moishe Greenberg) |

* Kaufmann, Yehezkel, ''The Religion of Israel, from Its Beginnings to the Babylonian Exile'', University of Chicago Press, 1960. (Translated by Moishe Greenberg) |

||

* Kugel, James L., ''How to Read the Bible: A Guide to Scripture, Then and Now'', Free Press, 2008. |

* Kugel, James L., ''How to Read the Bible: A Guide to Scripture, Then and Now'', Free Press, 2008. |

||

Conference, University of Queensland, St Lucia, Brisbane, Australia, Friday 2 October 2009'' |

|||

* Mendenhall, George E. ''The Tenth Generation: The Origins of the Biblical Tradition'', The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1973. |

* Mendenhall, George E. ''The Tenth Generation: The Origins of the Biblical Tradition'', The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1973. |

||

* Mendenhall, George E. ''Ancient Israel's Faith and History: An Introduction to the Bible in Context'', Westminster John Knox Press, 2001. ISBN 0-664-22313-3 |

* Mendenhall, George E. ''Ancient Israel's Faith and History: An Introduction to the Bible in Context'', Westminster John Knox Press, 2001. ISBN 0-664-22313-3 |

||

Revision as of 16:10, 26 September 2010

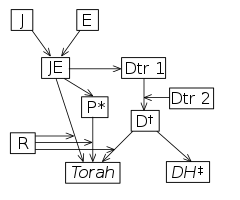

| * | includes most of Leviticus |

| † | includes most of Deuteronomy |

| ‡ | "Deuteronomic history": Joshua, Judges, 1 & 2 Samuel, 1 & 2 Kings |

The documentary hypothesis (DH) (sometimes called the Wellhausen hypothesis[1]), holds that the Pentateuch (the Torah, or the Five Books of Moses) was derived from originally independent, parallel and complete narratives, which were subsequently combined into the current form by a series of redactors (editors). The number of these is usually set at four, but this is not an essential part of the hypothesis.

In an attempt to reconcile inconsistencies in the biblical text, and refusing to accept traditional explanations to harmonize them, 18th and 19th century biblical scholars using source criticism eventually arrived at the theory that the Torah was composed of selections woven together from several, at times inconsistent, sources, each originally a complete and independent document[clarification needed]. The hypothesis developed slowly over the course of the 19th century, by the end of which it was generally agreed that there were four main sources, combined into their final form by a series of redactors, R. These four sources came to be known as the Yahwist, or Jahwist, J (J being the German equivalent of the English letter Y); the Elohist, E; the Deuteronomist, D, (the name comes from the Book of Deuteronomy, D's contribution to the Torah); and the Priestly Writer, P.[2]

Julius Wellhausen's contribution was to order these sources chronologically as JEDP, giving them a coherent setting in the evolving religious history of Israel, which he saw as one of ever-increasing priestly power. Wellhausen's formulation was:

- the Yahwist source ( J ) : written c. 950 BCE in the southern Kingdom of Judah.

- the Elohist source ( E ) : written c. 850 BCE in the northern Kingdom of Israel.

- the Deuteronomist ( D ) : written c. 600 BCE in Jerusalem during a period of religious reform.

- the Priestly source ( P ) : written c. 500 BCE by Aaronic priests in exile in Babylon.

- The Torah redactors: first JE, then JED, and finally JEDP, producing the final form of the Torah c. 450 BCE.

The hypothesis dominated biblical scholarship for much of the 20th century, and, although increasingly challenged by other models in the last part of the 20th century, its terminology and insights continue to provide the framework for modern theories on the origins of the Torah.[3]

| Part of a series on the |

| Bible |

|---|

|

|

Outline of Bible-related topics |

Outline of the hypothesis (Wellhausen's formulation)

The modern documentary hypothesis proposes that the Torah was originally four distinct narratives, each complete in itself, each dealing with the same incidents and characters, but with distinctive "messages". The four were combined twice by editors ("redactors") who strove to keep as much as possible of the original documents.

J, Jahwist source

The oldest source, concerned with narratives, making up half of Genesis and half of Exodus, plus fragments of Numbers. J describes a human-like God, called Yahweh (or rather YHWH) throughout, and has a special interest in the territory of the Kingdom of Judah and individuals connected with its history. J has an eloquent style. Originally composed c. 950 BCE.[4]

E, Elohist source

E parallels J, often duplicating the narratives. Makes up a third of Genesis and half of Exodus, plus fragments of Numbers. E describes a human-like God initially called Elohim, and Yahweh subsequent to the incident of the burning bush, at which Elohim reveals himself as Yahweh. E focuses on the Kingdom of Israel and on the Shiloh priesthood, has a moderately eloquent style. Originally composed c. 850 BCE.[4]

D, Deuteronomist source

D in the Pentateuch is restricted to the book of Deuteronomy, although it continues into the subsequent books of Joshua, Judges and Kings. It takes the form of a series of sermons about the Law, as well as recapitulating the narrative of Exodus and Numbers. Its distinctive term for God is YHWH Eloheinu, traditionally translated in English as "The Lord our God." Originally composed c. 650–621 BCE.[4]

P, Priestly source

P is preoccupied with lists (especially genealogies), dates, numbers and laws. P describes a distant and unmerciful God, referred to as Elohim. P partly duplicates J and E, but alters details to stress the importance of the priesthood. P consists of about a fifth of Genesis, substantial portions of Exodus and Numbers, and almost all of Leviticus. According to Wellhausen, P has a low level of literary style. Composed c. 600–400 BCE.[4]

R, Redactor

The first redaction of the Torah (Rd1) combined J and E to create JE, c 750 BCE. A second redactor combined JE with D and P to put the work into its final form c 400 BCE.

Before Wellhausen

Mosaic authorship

Prior to the 17th century both Jews and Christians accepted the traditional view that Moses had written the Torah under the direct inspiration—even dictation—of God. A few rabbis and philosophers asked how Moses could have described his own death (Deuteronomy 34:5–10), or given a list of the kings of Edom before those kings ever lived (Genesis 36:31–43), but none doubted the truth of the tradition, for the purpose of scholarship "was to underline the antiquity and authority of the teaching in the Pentateuch, not to demonstrate who wrote the books."[5]

The beginnings of the documentary hypothesis

Even in the Middle Ages some rabbis had voiced doubts about the traditional view, but in the 17th century it came under increasing and detailed scrutiny. In 1651 Thomas Hobbes, in chapter 33 of Leviathan, marshaled a battery of passages such as Deut 34:6 ("no man knoweth of his sepulchre to this day," implying an author living long after Moses' death); Gen 12:6 ("and the Canaanite was then in the land," implying an author living in a time when the Canaanite was no longer in the land); and Num 21:14 (referring to a previous book of Moses' deeds), and concluded that none of these could be by Moses. Others, including Isaac de la Peyrère, Baruch Spinoza, Richard Simon, and John Hampden came to the same conclusion, but their works were condemned, several of them were imprisoned and forced to recant, and an attempt was made on Spinoza's life.[6]

In 1753 Jean Astruc printed (anonymously) Conjectures sur les mémoires originaux, dont il paraît que Moïse s'est servi pour composer le livre de la Genèse ("Conjectures on the original accounts of which it appears Moses availed himself in composing the Book of Genesis"). Astruc's motive was to refute Hobbes and Spinoza – "the sickness of the last century," as he called their work. To do this, he applied to Genesis the tools of literary analysis which scholars were already using with Classical texts such as the Iliad to sift variant traditions and arrive at the most authentic text. He began by identifying two markers which seemed to identify consistent variations, the use of "Elohim" or "YHWH" (Yahweh) as the name for God, and the appearance of duplicated stories, or doublets, such as the two accounts of the creation in the first and second chapters of Genesis and the two accounts of Sarah and a foreign king (Gen.12 and Gen.20). He then ruled columns and assigned verses to these, the "Elohim" verses in one column, the "YHWH" verses in another, and the members of the doublets in their own columns beside these. The parallel columns thus constructed contained two long narratives, each dealing with the same incidents. Astruc suggested that these were the original documents used by Moses, and that Genesis as written by Moses had looked just like this, parallel accounts meant to be read separately. According to Astruc, a later editor had combined the columns into a single narrative, creating the confusions and repetitions noted by Hobbes and Spinoza.[7]

The tools adapted by Astruc for biblical source criticism were vastly developed by subsequent scholars, most of them German. From 1780 onwards Johann Gottfried Eichhorn extended Astruc's analysis beyond Genesis to the entire Pentateuch, and by 1823 he had concluded that Moses had had no part in writing any of it. In 1805 Wilhelm de Wette concluded that Deuteronomy represented a third independent source. About 1822 Friedrich Bleek identified Joshua as a continuation of the Pentateuch via Deuteronomy, while others identified signs of the Deuteronomist in Judges, Samuel, and Kings. In 1853 Hermann Hupfeld suggested that the Elohist was really two sources and should be split, thus isolating the Priestly source; Hupfeld also emphasized the importance of the Redactor, or final editor, in producing the Torah from the four sources. Not all the Pentateuch was traced to one or other of the four sources: numerous smaller sections were identified, such as the Holiness Code contained in Leviticus 17 to 26.[8]

Scholars also attempted to identify the sequence and dates of the four sources, and to propose who might have produced them, and why. De Wette had concluded in 1805 that none of the Pentateuch was composed before the time of David; since Spinoza, D was connected with the priests of the Temple in Jerusalem during the reign of Josiah in 621 BC; beyond this, scholars argued variously for composition in the order PEJD, or EJDP, or JEDP: the subject was far from settled.[9]

The Wellhausen (or Graf–Wellhausen) hypothesis

In 1876/77 Julius Wellhausen published Die Composition des Hexateuch ("The Composition of the Hexateuch", i.e. the Pentateuch plus the book of Joshua), in which he set out the four-source hypothesis of Pentateuchal origins; this was followed in 1878 by Prolegomena zur Geschichte Israels ("Prolegomena to the History of Israel"), a work which traced the development of the religion of the ancient Israelites from an entirely secular, non-supernatural standpoint. Wellhausen contributed little that was new, but sifted and combined the previous century of scholarship into a coherent, comprehensive theory on the origins of the Torah and of Judaism, one so persuasive that it dominated scholarly debate on the subject for the next hundred years.[2]

Distinguishing the sources

Wellhausen's criteria for distinguishing between sources were those developed by his predecessors over the previous century: style (including but not exclusively the choice of vocabulary); divine names; doublets and occasionally triplets. J was identified with a rich narrative style, E was somewhat less eloquent, P's language was dry and legalistic. Vocabulary items such as the names of God, or the use of Horeb (E and D) or Sinai (J and P) for God's mountain; ritual objects such as the ark, mentioned frequently in J but never in E; the status of judges (never mentioned in P) and prophets (mentioned only in E and D); the means of communication between God and humanity (J's God meets in person with Adam and Abraham, E's God communicates through dreams, P's can only be approached through the priesthood): all these and more formed the toolkit for discriminating between sources and allocating verses to them.[10]

Dating the sources

Wellhausen's starting point for dating the sources was the event described in 2 Kings 22:8–20: a "scroll of Torah" (which can be translated "instruction" or "law") is discovered in the Temple in Jerusalem by the High Priest Hilkiah in the eighteenth year of king Josiah, who had ascended the throne as a child of eight. What Josiah reads there causes him to embark on a campaign of religious reform, destroying all altars except that in the Temple, prohibiting all sacrifice except at the Temple, and insisting on the exclusive worship of Yahweh. In the 4th century Jerome had speculated that the scroll may have been Deuteronomy; de Wette in 1805 suggested that it might have been only the law-code at Deuteronomy 12–26 that Hilkiah found, and that he might have written it himself, alone or in collaboration with Josiah. The Deuteronomistic historian certainly held Josiah in high regard: 1 Kings 13 names him as one who will be sent by Yahweh to slaughter the apostate priests of Beth-el, in a prophecy allegedly made 300 years before his birth.[11]

With D anchored in history, Wellhausen proceeded to place the remaining sources around it. He accepted Karl Heinrich Graf's conclusion that the sources were written in the order J-E-D-P. This was contrary to the general opinion of scholars at the time, who saw P as the earliest of the sources, "the official guide to approved divine worship", and Wellhausen's sustained argument for a late P was the great innovation of the Prolegomena.[12] J and E he ascribed to the early monarchy, approximately 950 BCE for J and 850 BCE for E; P he placed in the early Persian post-Exilic period, around 500 BCE. His argument for these dates was based on what was seen in his day as the natural evolution of religious practice: in the pre-and early monarchic society described in Genesis and Judges and Samuel, altars were erected wherever the Patriarchs or heroes such as Joshua chose, anyone could offer the sacrifice, and portions were offered to priests as the one offering the sacrifice chose; by the late monarchy sacrifice was beginning to be centralized and controlled by the priesthood, while pan-Israelite festivals such as Passover were instituted to tie the people to the monarch in a joint celebration of national history; in post-Exilic times the temple in Jerusalem was firmly established as the only sanctuary, only the descendants of Aaron could offer sacrifices, festivals were linked to the calendar instead of to the seasons, and the schedule of priestly entitlements was strictly mandated.[13]

The four were combined by a series of Redactors (editors), first J with E to form a combined JE, then JE with D to form a JED text, and finally JED with P to form JEDP, the final Torah. Taking up a scholarly tradition stretching back to Spinoza and Hobbes, Wellhausen named Ezra, the post-Exilic leader who re-established the Jewish community in Jerusalem at the behest of the Persian emperor Artaxerxes I in 458 BCE, as the final redactor.

After Wellhausen

For much of the 20th century Wellhausen's hypothesis formed the framework within which the origins of the Pentateuch were discussed, and even the Vatican came to urge that "light derived from recent research" not be neglected by Catholic scholars, urging them especially to pay attention to "the sources written or oral" and "the forms of expression" used by the "sacred writer".[14] Some important modifications were introduced, notably by Albrecht Alt and Martin Noth, who argued for the oral transmission of ancient core beliefs—guidance out of Egypt, conquest of the Promised Land, covenants, revelation at Sinai/Horeb, etc.[15] Simultaneously, the work of the American Biblical archaeology school under William F. Albright seemed to confirm that even if Genesis and Exodus were only given their final form in the first millennium BC, they were still firmly grounded in the material reality of the second millennium.[16] The overall effect of such refinements was to aid the wider acceptance of the basic hypothesis by reassuring believers that even if the final form of the Pentateuch was late and not due to Moses himself, it was nevertheless possible to recover a credible picture of the period of Moses and of the patriarchal age. Hence, although challenged by scholars such as Umberto Cassuto, opposition to the documentary hypothesis gradually waned, and by the mid-twentieth century it was almost universally accepted.[17]

This changed when R. N. Whybray in 1987 restated almost identical arguments with far greater consequences. By that time three separate models for the composition of the Pentateuch had been proposed: the documentary (the Torah as a compilation of originally separate but complete books), the supplementary (a single original book, supplemented with later additions/deletions), and the fragmentary (many fragmentary works and editions). Whybray pointed out that of the three possible models the documentary was the most difficult to demonstrate, for while the supplemental and fragmentary models propose relatively simple, logical processes and can account for the unevenness of the final text, the process envisaged by the DH is both complex and extremely specific in its assumptions about ancient Israel and the development of its religion. Whybray went on to assert that these assumptions were illogical and contradictory, and did not offer real explanatory power: why, for example, should the authors of the separate sources avoid duplication, while the final redactor accepted it? "Thus the hypothesis can only be maintained on the assumption that, while consistency was the hallmark of the various [source] documents, inconsistency was the hallmark of the redactors!"[18]

Whybray's questions pertaining to the documentary hypothesis, however, have been largely answered[citation needed] by Joseph Blenkinsopp in recent times. At the end of the Jewish civil war when the northern and southern kingdoms were merged back together, each likely had their own versions of their ancient holy writings (although much of it may have been oral). Why would a redactor merge them together in such a way as to try to make both sides of the feud happy? Blenkinsopp asserts that the Jews during the Babylonian diaspora suddenly found themselves under Iranian rule when the Persians defeated the Babylonians. One aspect of the imperial policy was the insistence on local self-definition inscribed primarily in a codified and standardized corpus of traditional law backed by the central government and its regional representatives. Blenkinsopp suggests that the redaction may have served a political purpose for the Persians: to provide for the regional law that Judah would have been required to have. Having two or more versions of their history and laws is not very standardized. Thus we may now have the missing key as to why a redactor went about the task of trying to join together the separate versions of the feuding kingdoms.

Since Whybray there has been a proliferation of theories and models regarding the origins of the Torah, many of them radically different from Wellhausen's model. Thus, to mention some of the major figures from the last decades of the 20th century, H. H. Schmid almost completely eliminated J, allowing only a late Deuteronomical redactor.[19] With the idea of identifiable sources disappearing, the question of dating also changes its terms. Additionally, some scholars have abandoned the Documentary hypothesis entirely in favour of alternative models which see the Pentateuch as the product of a single author, or as the end-point of a process of creation by the entire community. Rolf Rendtorff and Erhard Blum saw the Pentateuch developing from the gradual accretion of small units into larger and larger works, a process which removes both J and E, and, significantly, implied a fragmentary rather than a documentary model for Old Testament origins;[20] and John Van Seters, using a different model, envisaged an ongoing process of supplementation in which later authors modified earlier compositions and changed the focus of the narratives.[21] The most radical contemporary proposal has come from Thomas L. Thompson, who suggests that the final redaction of the Torah occurred as late as the early Hasmonean monarchy.[citation needed]

The documentary hypothesis still has many supporters, especially in the United States, where William H. Propp has completed a two-volume translation and commentary on Exodus for the prestigious Anchor Bible Series from within a DH framework,[22] and Antony F. Campbell and Mark A. O’Brien have published a "Sources of the Pentateuch" presenting the Torah sorted into continuous sources following the divisions of Martin Noth. Richard Elliott Friedman's Who Wrote the Bible? (1987) and "The Bible with Sources Revealed" (2003) were in essence an extended response to Whybray, explaining, in terms based on the history of ancient Israel, how the redactors could have tolerated inconsistency, contradiction and repetition, indeed had it forced upon them by the historical setting in which they worked. Friedman's classic four-source division differed from Wellhausen in accepting Yehezkel Kaufmann's dating of P to the reign of Hezekiah;[23] this in itself is no small modification of Wellhausen, for whom a late dating of P was essential to his model of the historical development of Israelite religion. Friedman argued that J appeared a little before 722 BCE, followed by E, and a combined JE soon after that. P was written as a rebuttal of JE (c. 715–687 BCE), and D was the last to appear, at the time of Josiah (c. 622 BCE), before the Redactor, whom Friedman identifies as Ezra, collated the final Torah.

While the terminology and insights of the documentary hypothesis—notably its recognition that the Pentateuch is the work of many hands and many centuries, and that its final form belongs to the middle of the 1st millennium BC—continue to inform scholarly debate about the origins of the Pentateuch, it no longer dominates that debate as it did for the first two thirds of the 20th century. "The verities enshrined in older introductions [to the subject of the origins of the Pentateuch] have disappeared, and in their place scholars are confronted by competing theories which are discouragingly numerous, exceedingly complex, and often couched in an expository style that is (to quote John van Seter's description of one seminal work) 'not for the faint-hearted.'"[24]

See also

Notes

- ^ after Julius Wellhausen, though he did not invent it

- ^ a b A Basic Vocabulary of Biblical Studies For Beginning Students: A Work in Progress, Fred L. Horton, Kenneth G. Hoglund, and Mary F. Foskett, Wake Forest University, 2007

- ^ Wenham, Gordon. "Pentateuchal Studies Today", Themelios 22.1 (October 1996)

- ^ a b c d Harris, Stephen L., Understanding the Bible. Palo Alto: Mayfield. 1985.

- ^ Gordon Wenham. "Exploring the Old Testament: Vol. 1, the Pentateuch," p160 (2003).

- ^ For a brief overview of the Enlightenment struggle between scholarship and authority, see Richard Elliott Friedman, "Who Wrote the Bible?", pp.20–21 (hardback original 1987, paperback HarperCollins edition 1989).

- ^ Gordon Wenham, "Exploring the Old Testament: Volume 1, the Pentateuch", (2003), PP.162–163.

- ^ Richard Elliott Friedman, "Who Wrote the Bible?", pp.22–24.

- ^ Richard Elliott Friedman, "Who Wrote the Bible?", p.25., and Alexander Rofe, "Introduction to the Composition of the Pentateuch", (1999), ch.2. See also Raymond F. Surberg, "Wellhausianism Evaluated After a Century of Influence", section II, The Contribution of the Prolegomena from a Critical Viewpoint.

- ^ Richard Elliott Friedman, "The Bible with Sources Revealed", 2003; and Reading the Old Testament: Source Criticism.

- ^ Richard Elliott Friedman, "Who Wrote the Bible?" esp. p.188 ff.

- ^ Gordon Wenham, "Exploring the Old Testament", p.171.

- ^ This is a highly schematised account of a complex argument: see Gordon Wenham, "Exploring the Old Testament", pp.167–171.

- ^ "Let the interpreter then, with all care and without neglecting any light derived from recent research, endeavor to determine the peculiar character and circumstances of the sacred writer, the age in which he lived, the sources written or oral to which he had recourse and the forms of expression he employed." Encyclical Divino Afflante Spiritu, 1943.

- ^ Albecht Alt, "The God of the Fathers", 1929, and Martin Noth, "A History of Pentateuchal Traditions", 1948.

- ^ "Archaeology and the Patriarchs", an overview of archaeology and the Patriarchal period.

- ^ Gordon Wenham, "Pentateuchal Studies Today", Themelios 22.1 (October 1996)

- ^ R.N. Whybray, "The Making of the Pentateuch", 1987, quoted in Gordon Wenham, "Exploring the Old Testament", 2003, pp.173–174.

- ^ H. H. Schmid, "Der sogenannte Jahwist" ("The So-called Yahwist"), 1976.

- ^ Rolf Rendtdorff, The Problem of the Process of Transmission in the Pentateuch, Journal for the Study of the Old Testament Supplement 89, 1990.

- ^ John Van Seters, "Abraham in History and Tradition", 1975.

- ^ William H.C. Propp, "Exodus 1–18: A New Translation with Notes and Comments", Anchor Bible, 1999, and "Exodus 19–40: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary", 2006, both published by Anchor Bible.

- ^ Yehezkel Kaufmann, "The Religion of Israel, from Its Beginnings to the Babylonian Exile", 1961.

- ^ Benjamin Sommer, review of Ernest Nicholson's "The Pentateuch in the Twentieth Century: The Legacy of Julius Wellhausen", Review of Biblical Literature, 30 September 2000

Further reading

- Blenkinsopp, Joseph The Pentateuch : an introduction to the first five books of the Bible, Doubleday, NY, USA 1992. ISBN 038541207X

- Bloom, Harold and Rosenberg, David The Book of J, Random House, NY, USA 1990. ISBN 0-8021-4191-9.

- Campbell, Antony F., and O’Brien, Mark A. Sources of the Pentateuch, Fortress, Minneapolis, 1993.

- Friedman, Richard E. Who Wrote The Bible?, Harper and Row, NY, USA, 1987. ISBN 0-06-063035-3. This work does not constitute a standard reference for the documentary hypothesis, as Friedman in part describes his own theory of the origin of one of the sources. Rather, it offers an excellent introduction for the layperson.

- Friedman, Richard E. The Bible with Sources Revealed, HarperSanFrancisco, 2003. ISBN 0-06-053069-3.

- Garrett, Duane A. Rethinking Genesis: The Sources and Authorship of the First Book of the Bible, Mentor, 2003. ISBN 1-85792-576-9.

- Kaufmann, Yehezkel, The Religion of Israel, from Its Beginnings to the Babylonian Exile, University of Chicago Press, 1960. (Translated by Moishe Greenberg)

- Kugel, James L., How to Read the Bible: A Guide to Scripture, Then and Now, Free Press, 2008.

- Mendenhall, George E. The Tenth Generation: The Origins of the Biblical Tradition, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1973.

- Mendenhall, George E. Ancient Israel's Faith and History: An Introduction to the Bible in Context, Westminster John Knox Press, 2001. ISBN 0-664-22313-3

- Nicholson, Ernest Wilson. The Pentateuch in the Twentieth Century: The Legacy of Julius Wellhausen, Oxford University Press, 2003. ISBN 0198269587. This book is partially available on Google Books [1].

- Rofe, Alexander. Introduction to the Composition of the Pentateuch, Sheffield Academic Press, 1999.

- Rogerson, J. Old Testament Criticism in the Nineteenth Century: England and Germany, SPCK/Fortress, 1985.

- Shafer, Kenneth W. Searching for J, Gateway Press, Baltimore, 2003, ISBN 0-9747457-1-5, (Amazon)

- Spinoza, Benedict de A Theologico-Political Treatise Dover, New York, USA, 1951, Chapter 8.

- Tigay, Jeffrey H. "An Empirical Basis for the Documentary Hypothesis" Journal of Biblical Literature Vol.94, No.3 Sept. 1975, pages 329–342.

- Tigay, Jeffrey H., (ed.) Empirical Models for Biblical Criticism University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, PA, USA 1986. ISBN 081227976X

- Van Seters, John. Abraham in History and Tradition Yale University Press, 1975.

- Van Seters, John. In Search of History: Historiography in the Ancient World and the Origins of Biblical History Yale University Press, 1983.

- Van Seters, John. Prologue to History: The Yahwist as Historian in Genesis Westminster/John Knox, Louisville, Kentucky, 1992. ISBN 0664219675

- Van Seters, John. The Life of Moses: The Yahwist as Historian in Exodus–Numbers Louisville, Kentucky: Westminster/John Knox, 1994. ISBN 0-664-22363-X

- Wellhausen, Julius, "Prolegomena to the History of Israel", (the first English edition, with William Robertson Smith's Preface, from Project Guttenberg)

- Wenham, Gordon. "Pentateuchal Studies Today", Themelios 22.1 (October 1996): 3–13.

- Whybray, R. N. The Making of the Pentateuch: A Methodological Study JSOTSup 53. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1987.

External links

- Prolegomena to the History of Ancient Israel by Julius Wellhausen full text at sacred-texts.com

- Documentary Hypothesis (University of Maryland). Explanation of the DH, based on the Anchor Bible Dictionary entry on source criticism.

- Development of the Documentary Hypothesis (University of Maryland). A brief overview of the history of the DH, concentrating on the work of major scholars.

- Redaction Theory (documents hypothesis)

- Smith, Colin: "A Critical Assessment of the Graf-Wellhausen Documentary Hypothesis", June 2002. Retrieved from the Alpha and Omega Ministries website on 26 July 2006.

- Review of Bloom's "Book of J" with overview of current trends in biblical scholarship and DH

- The Documentary Hypothesis on the identity of the Pentateuch's authors on Religioustolerance.org, with the first ten chapters of Genesis color-coded by source

- JEDP vs Mosaic Authorship comparing JEDP criticism with Mosaic authorship defense

- A teaching guide for Bible education based on the documentary hypothesis

- " Does Anyone Still Believe the 'Documentary Hypothesis'?" Critique of JEDP by conservative Christians