German Americans: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

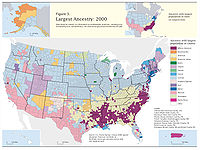

[[Image:Census-2000-Data-Top-US-Ancestries-by-County.jpg|thumb|200px|German Americans are common in the US. Light blue indicates counties that are predominately German ancestry.]] |

[[Image:Census-2000-Data-Top-US-Ancestries-by-County.jpg|thumb|200px|German Americans are common in the US. Light blue indicates counties that are predominately German ancestry.]] |

||

Revision as of 04:53, 5 March 2006

German Americans are citizens of the United States of German ancestry. Around 8 million German immigrants have entered the United States since its inception, with the majority arriving between 1840 and 1920. German immigrants arrived for a wide variety of reasons. Some came seeking religious or political freedom, others for economic opportunities greater than those in Germany, and others simply for the chance to start afresh in the New World. California and Pennsylvania have the largest German populations, with over 6 million Germans residing in the two states alone.

Numbering over 47 million, German Americans are the largest self-reported ethnic group in the United States.

First German Americans

German immigrants made up a substantial population of colonial Pennsylvania, where they often came into political conflict with the Quakers. The first German settlement in Pennsylvania was founded in 1683, although some Germans were already in America in other colonies at that time. Eventually, Germans would constitute about one-third of the population of Pennsylvania at the time of the Revolution.

A large German colony in Virginia called Germanna was located near Culpeper and was founded by two waves of colonists in 1714 and 1717. Many of these colonists were essentially hijacked to Virginia in questionable circumstances relating to Lt. Governor Alexander Spotswood, having intended to go to Pennsylvania. Many Germanna descendants took part in the Revolution and later were on the forefront of migration west to Kentucky and beyond.

In the 1790 U.S. census, the first taken by the new country, Germans are estimated to have constituted nearly 9% of the white population in the United States.

German Americans throughout the country

Germans trickled in to major US cities in response to the Industrial Revolution, and the demand for cheap immigrant labor made the US an attractive destination for immigration. Following the revolutions in German states in 1848, a wave of immigrant refugees flooded the United States and became known as Forty-Eighters. Heavy German immigration to the United States occurred between 1848 and World War I, during which time nearly 6 million Germans immigrated to the U.S. The Germans became widespread throughout the Northern half of the country, especially the Midwestern states. By 1900, the cities of Cleveland, Milwaukee, Hoboken and Cincinnati all had populations which were over 40% German. The Over-the-Rhine neighborhood in Cincinnati was one of the largest German American cultural centers. In Richmond, Virginia, German Americans were at least 30% of the population.

Present population

German Americans are the largest self-reported ethnic group in the United States today.

According to the 2000 U.S. census, 47 million Americans are of German ancestry. German Americans represent 16% of the total U.S. population and 24% of the non-Hispanic white population. Only 1.5 million of these speak German.

Of the four major U.S. regions, German was the most-reported ancestry in the Midwest, second in the West, and third in the Northeast and South regions. German was the top reported ancestry in 23 states, and it was one of the top five reported ancestries in every state except Maine and Rhode Island.

Diversity

The immigrants were as diverse as Germany itself, except that very few aristocrats or upper middle class businessmen came. For example, consider Texas, with about 20,000 Germans in the 1850s (from Handbook of Texas Online):

The Germans who settled Texas were diverse in many ways. They included peasant farmers and intellectuals; Protestants, Catholics, Jews, and atheists; Prussians, Saxons, Hessians, and Alsatians; abolitionists and slaveowners; farmers and townsfolk; frugal, honest folk and ax murderers. They differed in dialect, customs, and physical features. A majority had been farmers in Germany, and most came seeking economic opportunities. A few dissident intellectuals fleeing the 1848 revolutions sought political freedom, but few, save perhaps the Wends, came for religious freedom. The German settlements in Texas reflected their diversity. Even in the confined area of the Hill Country, each valley offered a different kind of German. The Llano valley had stern, teetotaling German Methodists, who renounced dancing and fraternal organizations; the Pedernales valley had fun-loving, hardworking Lutherans and Catholics who enjoyed drinking and dancing; and the Guadalupe valley had atheist Germans descended from intellectual political refugees. The scattered German ethnic islands were also diverse. These small enclaves included Lindsay in Cooke County, largely Westphalian Catholic; Waka in Ochiltree County, Midwestern Mennonite; Hurnville in Clay County, Russian German Baptist; and Lockett in Wilbarger County, Wendish Lutheran.

Religious affiliations

Immigrants from Germany in the 1800s brought many different religions with them. The largest numbers were generally Catholic or Lutheran, although the Lutherans were themselves split several ways. The more conservative groups comprised the Lutheran Church - Missouri Synod, based in Illinois, Wisconsin and Missouri, and the Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod. Other Lutherans formed a complex checkerboard of synods which in 1988 merged, along with Scandanavian synods, into the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America. Others were Reformed theological background, descendants of the 'evangelisch' or German "Evangelical Church" in Germany. Many immigrants joined quite different churches from those in Germany, especially the Methodist church.

Before 1800 communities of Amish, Mennonites and Hutterite had formed and are still in existence today. Some still speak dialects of German, including Pennsylvania German. Others immigrants were secular, rejecting formal religion. Many middle class Jewish immigrants became peddlers and storekeepers in small towns.

German American communities

Today, most German Americans have assimilated to the point that they no longer have readily identifiable ethnic communities, though there are still many metropolitan areas where German is the most reported ethnicity, such as Detroit, Chicago, Kansas City, Cleveland, Indianapolis, Minneapolis-St. Paul, St. Louis, Cincinnati, Louisville, Richmond, Virginia, and Milwaukee. The following list shows specifically German neighborhoods and areas that are now largely extinct. (It focuses on urban areas and does not include the rural areas extending from western New Jersey and Upstate New York to the Great Plains that were, or still are, heavily German.)

- Irvington, New Jersey

- Hoboken, New Jersey

- Over-the-Rhine, Cincinnati, Ohio

- Yorkville, Manhattan

- Woodhaven, Queens

- Ridgewood, Queens

- College Point, Queens

- Glendale, Queens

- Bushwick, Brooklyn

- Gerritsen Beach, Brooklyn

- Williamsburg, Brooklyn

- Lindenhurst, New York

- Rahway, New Jersey

- Lincoln Square, Chicago

- Foggy Bottom, Washington

Assimilation and World War I

After two or three generations in America the Germans assimilated to American customs--some of which they heavily influenced--and switched their language to English. As one scholar concludes, "The overwhelming evidence ... indicates that the German-American school was a bilingual one much (perhaps a whole generation or more) earlier than 1917, and that the majority of the pupils may have been English-dominant bilinguals from the early 1880's on." [1] By 1914 the older members were attending German language church services while the younger members were attending English services (in Lutheran, Evangelical and Catholic churches). In German parochial schools the children spoke English among themselves, though some of their classes were in German. In 1917-18, nearly all German language instruction ended, as did most (but not all) German language church services.

During World War I, German Americans, especially those born abroad, were sometimes accused of being too sympathetic to the German Empire. Theodore Roosevelt denounced "hyphenated Americanism" and insisted that dual loyalties were impossible in wartime. A small minority came out for Germany, including H. L. Mencken, who believed the German authoritarian system was superior to American democracy. Likewise Harvard psychology professor Hugo Munsterberg dropped his efforts to mediate between America and Germany and threw his efforts behind the German cause. See his obituary. Several thousand vocal opponents of the war were imprisoned.[2] Thousands were forced to buy war bonds to show their loyalty. One man was killed in Illinois. Some Germans during this time "Americanized" their names (e.g. Schmidt to Smith) and limited their use of the German language in public places. In Chicago Frederick Stock temporarily stepped down as conductor of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra until he finalized his naturalization papers. Berlioz replaced Wagner on programs. In Cincinnati, reaction to anti-German sentiment during World War I, caused the Public Library of Cincinnati to withdraw all German books from its shelves. [3] German-named streets were renamed [4]. Nebraska banned instruction in any language except English but the U.S. Supreme Court ruled the ban illegal in 1923 (Meyer v. Nebraska), by which time the nativist mood had largely subsided.

World War II

114,000 Germans came to the United States between 1931 and 1940, many of whom were anti-Nazis fleeing government oppression. [5] About 25,000 people became paying members of the pro-Nazi German American Bund during the years before the war. [6] German Americans who had been born overseas were the subject of some suspicion and discrimination during the war, although prejudice and sheer numbers meant they suffered less than Japanese Americans. The Alien Registration Act of 1940 required 300,000 German born U.S. resident aliens to register with the federal government and restricted their travel and property ownership rights. [7] [8] Under the still active Alien Enemy Act of 1798 the United States government interned nearly 11,000 German Americans between 1940 and 1948. Some of these were United States citizens. Civil rights violations occurred. 500 were arrested without warrant. Others were held without charge for months or interrogated without benefit of legal counsel. Convictions were not eligible for appeal. An unknown number of "voluntary internees" joined their spouses and parents in the camps and were not permitted to leave. [9] [10] [11] [12]

President Franklin D. Roosevelt kept his promise to German Americans that they would not be hounded as in 1917-1918. Roosevelt made a deliberate effort to name prominent German Americans to top war jobs, including General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Admiral Chester Nimitz, General Carl Spaatz, and Republican leader Wendell Willkie. German Americans who had fluent German language skills were an important asset to wartime intelligence, serving as translators and even as spies for the United States. [13] The war evoked complex reactions among German Americans, most of whom severed relationships with relatives in Europe and downplayed their ethnic heritage to blend with prevailing American culture. [14]

German American influence

Germans have contributed to a vast number of areas in American culture and technology. Baron von Steuben, a former Prussian officer, led the reorganization of the U.S. Army during the War for Independence and helped make the victory against British troops possible. The Steinway & Sons piano manufacturing firm was founded by immigrant Heinrich Engelhard Steinweg in 1853. German settlers brought the Christmas tree custom to the United States. The Studebakers built large numbers of wagons used during the Western migration; Studebaker later became an important early automobile manufacturer. Carl Schurz, a refugee from the unsuccessful first German democratic revolution of 1848 (see also German Confederation), served as U.S. Secretary of the Interior.

Due to the tragic developments in Germany leading from World War I and World War II, many researchers of German origin left Germany due to economic problems or as a result of racial, religious, and political persecution. Probably the most famous of them was Albert Einstein, known for his Theory of Relativity.

After World War II, Wernher von Braun, and most of the leading engineers from the former German rocket base Peenemünde, were brought to the U.S. They contributed to the development of U.S. military rockets, as well as of rockets for the NASA space program.

The influence of German cuisine is seen in the cuisine of the United States throughout the country. Frankfurters, hamburgers, bratwurst, sauerkraut, strudel are common dishes; some of these, like frankfurters and hamburgers, actually bear the names of German cities. Germans were important in the beer and wine industries. German bakers introduced the pretzel. The revival of microbreweries is partly due to instruction from German beer masters. See also Lager Beer Riot. The influence of German cuisine has faded--ther last German restaurant in downtown Chicago closed in 2005. There are remnants left in the rural Midwest/ Cincinnati, Ohio is known for its German American festival Zinzinnati, held annually. It is among the largest German American festivals in the U.S. Also Oktoberfest celebrations are held throughout the country.

German American presidents

There have been two presidents of the United States of America who were of German ancestry. One was Dwight Eisenhower (this surname was originally spelled Eisenhauer in Germany), the other was Herbert Hoover (original family name Huber).

References

- Colman J. Barry, The Catholic Church and German Americans. (1953)

- Angus Baxter, In Search of Your German Roots. The Complete Guide to Tracing Your Ancestors in the Germanic Areas of Europe. Fourth Edition (2001)

- Thomas Cochran, The Pabst Brewing Company: The History of an American Business (1948)

- Carol K. Coburn, Life at Four Corners: Religion, Gender, and Education in a German-Lutheran Community, 1868-1945 (1992).

- Kathleen Neils Conzen, Germans in Minnesota (2003)

- Dobbert, Guido .A. "German-Americans between New and Old Fatherland, 1870-1914". American Quarterly 19 ( 1967): 663-80. In JSTOR

- Ellis, M. and P. Panayi. "German Minorities in World War I: A Comparative Study of Britain and the USA." Ethnic and Racial Studies 17 ( April 1994): 238-59.

- Albert Bernhardt Faust. The German Element in the United States with Special Reference to Its Political, Moral, Social, and Educational Influence 2 vol (1909)

- Jon Gjerde, The Minds of the West: Ethnocultural Evolution in the Rural Middle West, 1830-1917 (1997)

- Gleason, Philip. The Conservative Reformers: American Catholics and the Social Order. (1968)

- Iverson, Noel. Germania, U.S.A.: Social Change in New Ulm, Minnesota. (1966), emphasizes Turners

- Jensen, Richard. The Winning of the Midwest, Social and Political Conflict 1888-1896" (1971), focus on voting behavior of Germans, prohibition issue, language issue and school issue

- Johnson, Hildegard B. "The Location of German Immigrants in the Middle West". Annals of the Association of American Geographers 41 (1951): 1-41. in JSTOR

- Jordon, Terry G. German Seed in Texas Soil: Immigrant Farmers in Nineteenth-century Texas. (1966)

- Kazal, Russell A. Becoming Old Stock: The Paradox of German-American Identity (2004) ethnicity and assimilation in 20c Philadelphia

- Kazal, Russell A. "Revisiting Assimilation: The Rise, Fall, and Reappraisal of a Concept." American Historical Review 100 (1995): 437-71. in JSTOR

- Luebke, Frederick C. Bonds of Loyalty: German Americans During World War I. (1974)

- Luebke, Frederick C. ed. Ethnic Voters and the Election of Lincoln (1971)

- Luebke, Frederick. Immigrants and Politics: the Germans of Nebraska, 1880-1900. (1969)

- O'Connor, Richard. German-Americans: an Informal History. (1968), popular

- Henry A. Pochmann, and Arthur R. Schultz; German Culture in America, 1600-1900: Philosophical and Literary Influences (1957)

- Roeber, A. G. Palatines, Liberty, and Property: German Lutherans in Colonial British America (1998)

- Thernstrom, Stephan ed. Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups (1973)

- Tischauser, Leslie V. The Burden of Ethnicity The German Question in Chicago, 1914-1941 1990.

- Tolzmann, Don H., ed. German Americans in the World Wars, vols. 1 and 2. Munich, Germany: K.G. Saur, 1995.

- Don Heinrich Tolzmann, The German-American Experience (2000)

- Carl Frederick Wittke, The German-Language Press in America (1957)

- Carl Wittke, Refugees of Revolution: The German Forty-Eighters in America (1952)

- Carl Wittke, We Who Built America: The Saga of the Immigrant (1939), ch 6, 9

- Wood, Ralph, ed. The Pennsylvania Germans. (1942)

- Catholic Encyclopedia article

See also

- Ethnic German

- German in the United States

- German-American relations

- History of Germany

- Immigration to the United States

- List of famous German Americans

- German-Brazilian