2 Pallas: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 216.36.2.237 (talk) to last version by AstroSteve |

|||

| Line 337: | Line 337: | ||

{{Link GA|es}} |

{{Link GA|es}} |

||

{{Link GA|it}} |

|||

[[als:(2) Pallas]] |

[[als:(2) Pallas]] |

||

[[ar:2 باللاس]] |

[[ar:2 باللاس]] |

||

Revision as of 12:07, 8 October 2011

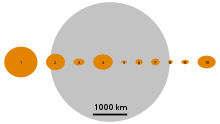

An ultraviolet image of Pallas showing flattened shape taken by the Hubble Telescope. | |

| Discovery | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | Heinrich Wilhelm Olbers |

| Discovery date | March 28, 1802 |

| Designations | |

| Pronunciation | /ˈpæləs/ [note 1] |

Named after | Pallas Athena |

| Pallas family | |

| Adjectives | Palladian[1] |

| Symbol | |

| Orbital characteristics[1][2] | |

| Epoch August 22, 2008 (JD 2454700.5) | |

| Aphelion | 3.412 AU (510.468 Gm) |

| Perihelion | 2.132 AU (319.005 Gm) |

| 2.772 AU (414.737 Gm) | |

| Eccentricity | 0.231 |

| 4.62 a (1686.044 d) | |

Average orbital speed | 17.65 km/s |

| 306.605° | |

| Inclination | 34.838° to Ecliptic 34.21° to Invariable plane[3] |

| 173.134° | |

| 310.274° | |

| Proper orbital elements[4] | |

Proper semi-major axis | 2.7709176 AU |

Proper eccentricity | 0.2812580 |

Proper inclination | 33.1988686° |

Proper mean motion | 78.041654 deg / yr |

Proper orbital period | 4.61292 yr (1684.869 d) |

Precession of perihelion | -1.335344 arcsec / yr |

Precession of the ascending node | −46.393342 arcsec / yr |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Dimensions | 582×556×500±18 km[5] 544 km (mean)[2] |

| Mass | (2.11±0.26)×1020 kg[6] |

Mean density | ~2.8 g/cm³[5] |

| ~0.18 m/s² | |

| ~0.32 km/s | |

| 0.325 55 d (7.8132 h)[7] | |

| likely 78 ± 13°[8] | |

| Albedo | 0.159 (geometric)[9] |

| Temperature | ~164 K max: ~265 K (-8 °C) |

Spectral type | B-type asteroid[10] |

| 6.4[11] to 10.6 | |

| 4.13[9] | |

| 0.59"[12] to 0.17" | |

Pallas, formally designated 2 Pallas, is the second asteroid to have been discovered, and one of the largest. It is estimated to constitute 7% of the mass of the asteroid belt,[13] and its diameter of 530–565 km is comparable to, or slightly larger than, that of 4 Vesta. It is however 20% less massive than Vesta,[6] placing it third among the asteroids. It is possibly the largest irregularly shaped body in the Solar System (that is, the largest body not rounded under its own gravity)[not verified in body], and a remnant protoplanet.

When Pallas was discovered by astronomer Heinrich Wilhelm Matthäus Olbers on March 28, 1802, it was counted as a planet, as were other asteroids in the early 19th century. The discovery of many more asteroids after 1845 eventually led to their re-classification.

The Palladian surface appears to be a silicate material; the surface spectrum and estimated density resemble carbonaceous chondrite meteorites. The Palladian orbit, at 34.8°, is unusually highly inclined to the plane of the asteroid belt, and the orbital eccentricity is nearly as large as that of Pluto, making Pallas relatively inaccessible to spacecraft.[14][15]

Name

2 Pallas is named after Pallas Athena, an alternate name for the goddess Athena.[16][17] In some mythologies Athena killed Pallas, then adopted her friend's name out of mourning.[18] (There are several male characters of the same name in Greek mythology, but the first asteroids were invariably given female names.)[19]

The stony-iron Pallasite meteorites are not connected to the Pallas asteroid, being instead named after the German naturalist Peter Simon Pallas. The chemical element palladium, on the other hand, was named after the asteroid, which had been discovered just before the element.[20]

As with other asteroids, the astronomical symbol for Pallas is a disk with its discovery number, ②. However, it also has an older, more iconic symbol, ⚴ (![]() or sometimes

or sometimes ![]() ).[21]

).[21]

History of observation

In 1801, the astronomer Giuseppe Piazzi discovered an object which he initially believed to be a comet. Shortly thereafter he announced his observations of this object, noting that the slow, uniform motion was uncharacteristic of a comet, suggesting it was a different type of object. This was lost from sight for several months, but was recovered later in the year by the Baron von Zach and Heinrich W. M. Olbers after a preliminary orbit was computed by Friedrich Gauss. This object came to be named Ceres, and was the first asteroid to be discovered.[22][23]

A few months later, Olbers was again attempting to locate Ceres when he noticed another moving object in the vicinity. This was the asteroid Pallas, coincidentally passing near Ceres at the time. The discovery of this object created interest in the astronomy community. Before this point it had been speculated by astronomers that there should be a planet in the gap between Mars and Jupiter. Now, unexpectedly, a second such body had been found.[24] When Pallas was discovered some estimates of its size were as high as 3,380 km in diameter.[25] Even as recently as 1979, Pallas was estimated to be 673 km in diameter (26% greater than the currently accepted value).[26]

The orbit of Pallas was determined by Gauss, who found the period of 4.6 years was similar to the period for Ceres. However, Pallas had a relatively high orbital inclination to the plane of the ecliptic.[24]

In 1917, the Japanese astronomer Kiyotsugu Hirayama began to study asteroid motions. By plotting the mean orbital motion, inclination and eccentricity of a set of asteroids, he discovered several distinct groupings. In a later paper he reported a group of three asteroids associated with Pallas, which became named the Pallas family after the largest member of the group.[28] Since 1994 more than 10 members of this family have been identified, and these have semi-major axes between 2.50–2.82 AU and inclinations of 33–38°.[29] The validity of this grouping was confirmed in 2002 by a comparison of their spectra.[30]

Pallas has been observed occulting a star several times, including the best observed of all asteroid occultation events on May 29, 1983, when careful occultation timing measurements were taken by 140 observers. These resulted in the first accurate measurements of its diameter.[31][32] During the occultation of May 29, 1979 the discovery of a possible tiny satellite with a diameter of about 1 km was reported. However, it could not be confirmed. In 1980, speckle interferometry was reported as indicating a much larger satellite with a diameter of 175 km, but the existence of the satellite was later refuted.[33]

Radio signals from spacecraft in orbit around Mars and/or on its surface have been used to estimate the mass of Pallas from the tiny perturbations induced by it onto the motion of Mars.[34]

The Dawn Mission team was granted viewing time on the Hubble Space Telescope in September 2007 for a once-in-twenty-year opportunity to view the asteroid at closest approach, to obtain comparative data for Ceres and Vesta.[5][35]

Characteristics

Both Vesta and Pallas have assumed the title of second-largest asteroid from time to time.[36] However, while Pallas is similar to 4 Vesta in volume,[37] it is significantly less massive. The mass of Pallas is only 22% of Ceres,[13] and about 0.3% that of the Moon.

Pallas is farther from the Earth with a much lower albedo than Vesta, and consequently appears dimmer. Indeed, the much smaller 7 Iris marginally exceeds Pallas in mean opposition magnitude.[38] Pallas' mean opposition magnitude is +8.0, which is well within the range of 10×50 binoculars, but unlike Ceres and Vesta, it will require more powerful optical aid to view at small elongations, when its magnitude can drop as low as +10.6. During rare perihelic oppositions, Pallas can reach a magnitude of +6.4, right on the edge of naked-eye visibility.[11] During late February 2014, Pallas will shine at magnitude 6.96.[12]

Pallas has unusual dynamic parameters for such a large body. Its orbit is highly inclined and somewhat eccentric, despite being at the same distance from the Sun as the central part of the asteroid belt. Furthermore, its axial tilt is very high, either 78±13° or 65±12° (based on ambiguous lightcurve data, the pole points towards either ecliptic coordinates (β, λ) = (−12°, 35°) or (43°, 193°) with a 10° uncertainty;[8] data from the Hubble Space Telescope obtained in 2007 as well as the observations by the Keck telescope in 2003–2005 favour the first solution.[5][39]) This means that, every Palladian summer and winter, large parts of the surface are in constant sunlight or constant darkness for a time of the order of an Earth year.

Based on spectroscopic observations, the primary component of the Palladian surface material is a silicate that is low in iron and water. Minerals of this type include olivine and pyroxene, which are found in CM chondrules.[40] The surface composition of Pallas is very similar to the Renazzo carbonaceous chondrite (CR) meteorites, which are even lower in hydrous minerals than the CM type.[41] The Renazzo meteorite was discovered in Italy in 1824 and is one of the most primitive meteorites known.[42]

Very little is known of Palladian surface features. Hubble images from 2007 show pixel-to-pixel variation (pixel resolution is ~70 km), but Pallas' 12% albedo placed such features at the lower end of detectability. There is little variability between lightcurves obtained through visible-light and infrared filters, but significant deviations in the ultraviolet, suggesting large surface or compositional features near 285° (75° west longitude). Rotation appears to be prograde.[5]

Pallas is believed to have undergone at least some degree of thermal alteration and partial differentiation,[5] which suggests that it was a protoplanet. During the planetary formation stage of the Solar System, objects grew in size through an accretion process to approximately this size. Many of these objects were incorporated into larger bodies, which became the planets, while others were destroyed in collisions with other protoplanets. Pallas and Vesta are likely survivors from this early stage of planetary formation.[43]

Pallas was among the "candidate planets" in an early draft of the IAU's 2006 definition of planet, but does not qualify in the final definition because it has not "cleared the neighborhood" around its orbit.[44][45] In the future, it is possible that Pallas may be classified as a dwarf planet, if it is found to have a surface shaped by hydrostatic equilibrium.

Near resonances

Pallas is in a near-1:1 mean-motion orbital resonance with Ceres.[46] Pallas also has a near-18:7 resonance (6500-year period) and an approximate 5:2 resonance (83-year period) with Jupiter.[47]

Transits of planets from Pallas

From Pallas, Mercury, Venus, Mars, and the Earth can occasionally appear to transit, or pass in front of, the Sun. The Earth last did so in 1968 and 1998, and will next transit in 2224. Mercury did in October 2009. The last and next by Venus are in 1677 and 2123, and for Mars they are in 1597 and 2759.[48]

Exploration

Pallas has not been visited by spacecraft, but if the Dawn probe is successful in studying 4 Vesta and 1 Ceres, and if sufficient fuel remains, it is possible its mission may be extended to include a flyby of Pallas as Pallas crosses the ecliptic in 2018. However, due to the high orbital inclination of Pallas, it will not be possible for Dawn to enter orbit.[36][49]

See also

Notes

- ^ In US dictionary transcription, Template:USdict. Or as [Παλλάς] Error: {{Lang-xx}}: text has italic markup (help).

References

- ^ OED

- ^ a b "JPL Small-Body Database Browser: 2 Pallas". Retrieved 2009-09-12.

- ^ "The MeanPlane (Invariable plane) of the Solar System passing through the barycenter". 2009-04-03. Archived from the original on 2009-05-14. Retrieved 2009-04-10.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) (produced with Solex 10 written by Aldo Vitagliano; see also Invariable plane). Retrieved 2009-04-25. - ^ "AstDyS-2 Pallas Synthetic Proper Orbital Elements". Department of Mathematics, University of Pisa, Italy. Retrieved 2011-10-01.

- ^ a b c d e f

Schmidt, B. E.; et al. (2008). "Hubble takes a look at Pallas: Shape, size, and surface" (PDF). 39th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (Lunar and Planetary Science XXXIX). Held March 10–14, 2008, in League City, Texas. 1391: 2502. Retrieved 2008-08-24.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ a b

Baer, James (2008). "Astrometric masses of 21 asteroids, and an integrated asteroid ephemeris" (PDF). Celestial Mechanics and Dynamical Astronomy. 100 (2008). Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2007: 27–42. Bibcode:2008CeMDA.100...27B. doi:10.1007/s10569-007-9103-8. Retrieved 2008-11-11.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^

Harris, A. W. (2006). "Asteroid Lightcurve Derived Data. EAR-A-5-DDR-Derived-Lightcurve-V8.0". NASA Planetary Data System. Archived from the original on 2007-01-28. Retrieved 2007-03-15.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Torppa, J.; et al. (2003). "Shapes and rotational properties of thirty asteroids from photometric data". Icarus. 164 (2): 346–383. Bibcode:2003Icar..164..346T. doi:10.1016/S0019-1035(03)00146-5.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ a b

Tedesco, E. F. (2004). "IRAS Minor Planet Survey. IRAS-A-FPA-3-RDR-IMPS-V6.0". NASA Planetary Data System. Archived from the original on 2007-03-11. Retrieved 2007-03-15.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^

Neese, C. (2005). "Asteroid Taxonomy. EAR-A-5-DDR-Taxonomy-V5.0". NASA Planetary Data System. Archived from the original on 2007-03-10. Retrieved 2007-03-15.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b

Menzel, Donald H.; Pasachoff, Jay M. (1983). A Field Guide to the Stars and Planets (2nd ed.). Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin. p. 391. ISBN 0-395-34835-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Calculated with JPL Horizons for 2014-Feb-24

- ^ a b Pitjeva, E. V. (2005). "High-Precision Ephemerides of Planets—EPM and Determination of Some Astronomical Constants" (PDF). Solar System Research. 39 (3): 176. Bibcode:2005SoSyR..39..176P. doi:10.1007/s11208-005-0033-2.

- ^ Pallasite meteorites are named for an involved scientist who characterised them, not for this asteroid and they do not necessarily share origin with Pallas. Anonymous (2007-11-05). "Pre-Dawn: The French-Soviet VESTA mission". Space Files. Retrieved 2008-06-28.

- ^ Anonymous. "Space Topics: Asteroids and Comets, Notable Comets". The Planetary Society. Retrieved 2008-06-28.

- ^ James, Andrew (September 1, 2006). "Pallas: 2006–2015". Southern Astronomical Delights. Retrieved 2007-03-29.

- ^ "Athena". 1911 Edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica. Encyclopaedia Britannica (Tim Starling). Retrieved 2008-08-16.

- ^ Dietrich, Thomas (2005). The Origin of Culture and Civilization: The Cosmological Philosophy of the Ancient Worldview Regarding Myth, Astrology, Science, and Religion. Turnkey Press. p. 178. ISBN 0-9764981-6-2.

- ^ Since Pallas is already a Greek name, the asteroid has the same name in Greek, unlike 1 Ceres, 3 Juno, and 4 Vesta. All other languages, with one exception, use Pallas or national variants of that name: Italian Pallade, Russian Pallada, Spanish Palas, Arabic Bālās. The one exception is Chinese, in which Pallas is called the 'wisdom-god(dess) star' (智神星 zhìshénxīng). This is in contrast to the goddess Pallas, where Chinese uses the Greek name (帕拉斯 pàlāsī).

- ^ "Palladium". Los Alamos National Laboratory. Retrieved 2007-03-28.

- ^ Unicode value U+26B4

- ^ Hoskin, Michael (1992-06-26). "Bode's Law and the Discovery of Ceres". Observatorio Astronomico di Palermo "Giuseppe S. Vaiana". Retrieved 2007-07-05.

- ^ Forbes, Eric G. (1971). "Gauss and the Discovery of Ceres". Journal for the History of Astronomy. 2: 195–199. Bibcode:1971JHA.....2..195F.

- ^ a b "Astronomical Serendipity". NASA JPL. Retrieved 2007-03-15.

- ^ Hilton, James L. (2007-11-16). "When did asteroids become minor planets?". U.S. Naval Observatory. Retrieved 2011-09-09.

- ^ Hilton, James L. "Asteroid Masses and Densities" (PDF). U.S. Naval Observatory. Retrieved 2008-09-07.

- ^ O. Gingerich (2006). "The Path to Defining Planets" (PDF). Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics and IAU EC Planet Definition Committee chair. Retrieved 2007-03-13.

- ^ Kozai, Yoshihide (November 29-December 3, 1993). "Kiyotsugu Hirayama and His Families of Asteroids (invited)". Proceedings of the International Conference. Sagamihara, Japan: Astronomical Society of the Pacific. Retrieved 2007-01-08.

{{cite conference}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Faure, Gérard (May 20, 2004). "Description of the System of Asteroids". Astrosurf.com. Archived from the original on 2007-02-02. Retrieved 2007-03-15.

- ^ Foglia, S.; Masi, G. (1999). "New clusters for highly inclined main-belt asteroids". The Minor Planet Bulletin. 31: 100–102. Retrieved 2007-03-15.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

Drummond, J. D.; Cocke, W. J. (1989). "Triaxial ellipsoid dimensions and rotational pole of 2 Pallas from two stellar occultations". Icarus. 78 (2): 323–329. Bibcode:1989Icar...78..323D. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(89)90180-2.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dunham, D. W.; et al. (1990). "The size and shape of (2) Pallas from the 1983 occultation of 1 Vulpeculae". Astronomical Journal. 99: 1636–1662. Bibcode:1990AJ.....99.1636D. doi:10.1086/115446.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Johnston, William Robert (March 5, 2007). "Other Reports of Asteroid/TNO Companions". Johnson's Archive. Retrieved 2007-03-14.

- ^ Pitjeva, E. V. (2004). "Estimations of masses of the largest asteroids and the main asteroid belt from ranging to planets, Mars orbiters and landers". 35th COSPAR Scientific Assembly. Held 18–25 July 2004, in Paris, France. p. 2014.

{{cite conference}}: Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Staff (October 24, 2007). "Hubble Images of Asteroids Help Astronomers Prepare for Spacecraft Visit". JPL/NASA. Retrieved 2007-10-27.

- ^ a b "Notable Asteroids". The Planetary Society. 2007. Retrieved 2007-03-17.

- ^ The volume of Pallas is indistinguishable from that of Vesta given the uncertainties of current measurements.

- ^ Odeh, Moh'd. "The Brightest Asteroids". Jordanian Astronomical Society. Retrieved 2007-07-16.

- ^

Carry, B.; et al. (2007). "Asteroid 2 Pallas Physical Properties from Near-Infrared High-Angular Resolution Imagery" (PDF). Retrieved 2009-06-22.

{{cite web}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^

Feierberg, M. A.; Larson, H. P.; Lebofsky, L. A. (1982). "The 3 Micron Spectrum of Asteroid 2 Pallas". Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society. 14: 719. Bibcode:1982BAAS...14..719F.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

Sato, Kimiyasu; Miyamoto, Masamichi; Zolensky, Michael E. (1997). "Absorption bands near 3 m in diffuse reflectance spectra of carbonaceous chondrites: Comparison with asteroids". Meteoritics. 32 (4): 503–507. Bibcode:1997M&PS...32..503S. doi:10.1111/j.1945-5100.1997.tb01295.x.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Earliest Meteorites Provide New Piece in Planetary Formation Puzzle". Particle Physics and Astronomy Research Council. September 20, 2005. Retrieved 2006-05-24.

- ^

McCord, T. B.; McFadden, L. A.; Russell, C. T.; Sotin, C.; Thomas, P. C. (2006). "Ceres, Vesta, and Pallas: Protoplanets, Not Asteroids". Transactions of the American Geophysical Union. 87 (10): 105. Bibcode:1998RPPh...61...77K. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/61/2/001.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "IAU 2006 General Assembly: Result of the IAU Resolution votes". IAU. Retrieved 2008-08-16.

- ^ Rincon, Paul (August 16, 2006). "Planets plan boosts tally to 12". BBC News. Retrieved 2007-03-17.

- ^ Goffin, E. (2001). "New determination of the mass of Pallas". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 365 (3): 627–630. Bibcode:2001A&A...365..627G. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20000023.

- ^ Taylor, D. B. (1982). "The secular motion of Pallas". Royal Astronomical Society. 199: 255–265. Bibcode:1982MNRAS.199..255T.

- ^ "Solex by Aldo Vitagliano". Archived from the original on 2009-04-29. Retrieved 2009-03-19.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) (numbers generated by Solex) - ^

Perozzi, Ettore (2001). "Basic targeting strategies for rendezvous and flyby missions to the near-Earth asteroids". Planetary and Space Science. 49 (1): 3–22. Bibcode:2001P&SS...49....3P. doi:10.1016/S0032-0633(00)00124-0.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

External links

- Computer-generated shape of Pallas (Gable, 2009)

- Mona Gable. "Study of first high-resolution images of Pallas confirms asteroid is actually a protoplanet". University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). Retrieved October 20, 2009.

- Jonathan Amos (2009-10-11). "Pallas is 'Peter Pan' space rock". BBC. Retrieved August 19, 2010.

- "2 Pallas". JPL Small-Body Database Browser. Retrieved 2007-03-29.

- Dunn, Tony (2006). "Ceres, Pallas Vesta and Hygeia". GravitySimulator.com. Retrieved 2007-03-15.

- Hilton, James L. (April 1, 1999). "U.S. Naval Observatory Ephemerides of the Largest Asteroids". U.S. Naval Observatory. Retrieved 2007-03-14.

- Tedesco, Edward F.; Noah, Paul V.; Noah, Meg; Price, Stephan D. (2002). "The Supplemental IRAS Minor Planet Survey". The Astronomical Journal. 123 (2): 1056–1085. Bibcode:2002AJ....123.1056T. doi:10.1086/338320.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Yeomans, Donald K. "Horizons system". NASA JPL. Retrieved 2007-03-20.—Horizons can be used to obtain a current ephemeris.