Instructional design: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Ringring91 (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 69: | Line 69: | ||

Some educators believe that Gagné's taxonomy of learning outcomes and principles of instruction oversimplify the learning process by over prescribing.<ref>Haines, D. (1996). Gagné. [On-Line]. Available: http://education.indiana.edu/~educp540/haines1.html</ref> While it is true that using the theory solely in any educational setting would never work, using them as part of a complete instructional package can assist many educators in becoming more organized and staying focused on the instructional goals.<ref>Dowling, L. J. (2001). Robert Gagné and the Conditions of Learning. Walden University.</ref> |

Some educators believe that Gagné's taxonomy of learning outcomes and principles of instruction oversimplify the learning process by over prescribing.<ref>Haines, D. (1996). Gagné. [On-Line]. Available: http://education.indiana.edu/~educp540/haines1.html</ref> While it is true that using the theory solely in any educational setting would never work, using them as part of a complete instructional package can assist many educators in becoming more organized and staying focused on the instructional goals.<ref>Dowling, L. J. (2001). Robert Gagné and the Conditions of Learning. Walden University.</ref> |

||

==== Gagné's Influence on Education Today ==== |

|||

Gagné's continuing influence on education has been best developed in The Legacy of Robert M. Gagné (Richey, 2000).<ref> Richey, R. C. (2000). The legacy of Robert M. Gagne. Syracuse, NY: ERIC Clearinghouse on Information & Technology. |

|||

Gagné (1966) defines curriculum as . . . |

|||

. . . a sequence of content units arranged in such a way that the learning of each unit may be accomplished as a single act, provided the capabilities described by specified prior units (in the sequence) have already been mastered by the learner. (p. 188)<ref> Richey, R. C. (2000). The legacy of Robert M. Gagne. Syracuse, NY: ERIC Clearinghouse on Information & Technology. |

|||

His definition of curriculum has been the basis of many important initiatives in schools and other educational environments (p.188).<ref> Richey, R. C. (2000). The legacy of Robert M. Gagne. Syracuse, NY: ERIC Clearinghouse on Information & Technology. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Gagné had expressed and established an interest in applying theory to practice with particular interest in applications for teaching, training and learning. Increasing the effectiveness and efficiency of practice was of particular concern (p.185).<ref> Richey, R. C. (2000). The legacy of Robert M. Gagne. Syracuse, NY: ERIC Clearinghouse on Information & Technology. His ongoing attention to practice while developing theory continues to have an impact on education and training (p.188). |

|||

==Learning design== |

==Learning design== |

||

Revision as of 20:01, 12 April 2012

The examples and perspective in this article may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (August 2010) |

Instructional Design (also called Instructional Systems Design (ISD)) is the practice of creating "instructional experiences which make the acquisition of knowledge and skill more efficient, effective, and appealing."[1] The process consists broadly of determining the current state and needs of the learner, defining the end goal of instruction, and creating some "intervention" to assist in the transition. Ideally the process is informed by pedagogically (process of teaching) and andragogically (adult learning) tested theories of learning and may take place in student-only, teacher-led or community-based settings. The outcome of this instruction may be directly observable and scientifically measured or completely hidden and assumed. There are many instructional design models but many are based on the ADDIE model with the five phases: 1) analysis, 2) design, 3) development, 4) implementation, and 5) evaluation. As a field, instructional design is historically and traditionally rooted in cognitive and behavioral psychology, though recently Constructivism (learning theory) has influenced thinking in the field.[2][3] [4]

History

Much of the foundations of the field of instructional design was laid in World War II, when the U.S. military faced the need to rapidly train large numbers of people to perform complex technical tasks, from field-stripping a carbine to navigating across the ocean to building a bomber—see "Training Within Industry (TWI)". Drawing on the research and theories of B.F. Skinner on operant conditioning, training programs focused on observable behaviors. Tasks were broken down into subtasks, and each subtask treated as a separate learning goal. Training was designed to reward correct performance and remediate incorrect performance. Mastery was assumed to be possible for every learner, given enough repetition and feedback. After the war, the success of the wartime training model was replicated in business and industrial training, and to a lesser extent in the primary and secondary classroom. The approach is still common in the U.S. military.[5]

In 1956, a committee led by Benjamin Bloom published an influential taxonomy of what he termed the three domains of learning: Cognitive (what one knows or thinks), Psychomotor (what one does, physically) and Affective (what one feels, or what attitudes one has). These taxonomies still influence the design of instruction.[6]

During the latter half of the 20th century, learning theories began to be influenced by the growth of digital computers.

In the 1970s, many instructional design theorists began to adopt an information-processing-based approach to the design of instruction. David Merrill for instance developed Component Display Theory (CDT), which concentrates on the means of presenting instructional materials (presentation techniques).[7]

Later in the 1980s and throughout the 1990s cognitive load theory began to find empirical support for a variety of presentation techniques.[8]

Cognitive load theory and the design of instruction

Cognitive load theory developed out of several empirical studies of learners, as they interacted with instructional materials.[9] Sweller and his associates began to measure the effects of working memory load, and found that the format of instructional materials has a direct effect on the performance of the learners using those materials.[10][11][12]

While the media debates of the 1990s focused on the influences of media on learning, cognitive load effects were being documented in several journals. Rather than attempting to substantiate the use of media, these cognitive load learning effects provided an empirical basis for the use of instructional strategies. Mayer asked the instructional design community to reassess the media debate, to refocus their attention on what was most important: learning.[13]

By the mid- to late-1990s, Sweller and his associates had discovered several learning effects related to cognitive load and the design of instruction (e.g. the split attention effect, redundancy effect, and the worked-example effect). Later, other researchers like Richard Mayer began to attribute learning effects to cognitive load.[13] Mayer and his associates soon developed a Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning.[14][15][16]

In the past decade, cognitive load theory has begun to be internationally accepted[17] and begun to revolutionize how practitioners of instructional design view instruction. Recently, human performance experts have even taken notice of cognitive load theory, and have begun to promote this theory base as the science of instruction, with instructional designers as the practitioners of this field.[18] Finally Clark, Nguyen and Sweller[19] published a textbook describing how Instructional Designers can promote efficient learning using evidence-based guidelines of cognitive load theory.

Instructional Designers use various instructional strategies to reduce cognitive load. For example, they think that the onscreen text should not be more than 150 words or the text should be presented in small meaningful chunks.[citation needed] The designers also use auditory and visual methods to communicate information to the learner.

Gagné's Theory of Instruction

Gagné's instructional theory is widely used in the design of instruction by instructional designers in many settings, and its continuing influence in the field of educational technology can be seen in the more than 130 times that Gagné has been cited in prominent journals in the field during the period from 1985 through 1990. [20] Synthesizing ideas from behaviorism and cognitivism, he provides a clear template, which is easy to follow for designing instructional events. Instructional designers who follow Gagné's theory will likely have tightly focused, efficient instruction.[21]

Overview of Gagne’s instructional theory

A taxonomy of Learning Outcomes

Robert Gagné [23]classified the types of learning outcomes. A good way to identify the types of learning is to ask how learning might be demonstrated:

- Cognitive Domain

- Intellectual skills - concepts are demonstrated by labeling or classifying things

- Intellectual skills - rules are applied and principles are demonstrated

- Intellectual skills - problem solving allows generating solutions or procedures

- Cognitive strategies - are used for learning

- Verbal information - is stated

- Affective Domain

- Attitudes - are demonstrated by preferring options

- Psychomotor Domain

- Motor skills - enable physical performance

Conditions for Learning

Gagné, & Driscoll [24], developed the following conditions of learning with standard verbs to correspond to the learning outcomes:

- Verbal Information: state, recite, tell, declare

- Intellectual Skills

- Discrimination: discriminate, distinguish, differentiate

- Concrete Concept: identify, name, specify, label

- Defined Concept: classify, categorize, type, sort (by definition)

- Rule: demonstrate, show, solve (using one rule)

- Higher Order Rule: generate, develop, solve (using two or more rules)

- Cognitive Strategy: adopt, create, originate

- Attitude: choose, prefer, elect, favor

- Motor Skill: execute, perform, carry out

The Nine Events of Instruction

According to Gagné, learning is a step-by-step process. Each step must be accomplished before the next in order for learning to take place.

- Gaining attention: To ensure reception of coming instruction, the teacher gives the learners a stimulus. Before the learners can start to process any new information, the instructor must gain the attention of the learners. This might entail using abrupt changes in the instruction.

- Informing learners of objectives: The teacher tells the learner what they will be able to do because of the instruction. The teacher communicates the desired outcome to the group.

- Stimulating recall of prior learning: The teacher asks for recall of existing relevant knowledge.

- Presenting the stimulus: The teacher gives emphasis to distinctive features.

- Providing learning guidance: The teacher helps the students in understanding (semantic encoding) by providing organization and relevance.

- Eliciting performance: The teacher asks the learners to respond, demonstrating learning.

- Providing feedback: The teacher gives informative feedback on the learners' performance.

- Assessing performance: The teacher requires more learner performance, and gives feedback, to reinforce learning.

- Enhancing retention and transfer: The teacher provides varied practice to generalize the capability.

Some educators believe that Gagné's taxonomy of learning outcomes and principles of instruction oversimplify the learning process by over prescribing.[25] While it is true that using the theory solely in any educational setting would never work, using them as part of a complete instructional package can assist many educators in becoming more organized and staying focused on the instructional goals.[26]

Gagné's Influence on Education Today

Gagné's continuing influence on education has been best developed in The Legacy of Robert M. Gagné (Richey, 2000).Cite error: A <ref> tag is missing the closing </ref> (see the help page). with the idea that "designers and instructors need to choose for themselves the best mixture of behaviourist and constructivist learning experiences for their online courses".[27] But the concept of learning design is probably as old as the concept of teaching. Learning design might be defined as "the description of the teaching-learning process that takes place in a unit of learning (eg, a course, a lesson or any other designed learning event)".[28]

As summarized by Britain,[29] learning design may be associated with:

- The concept of learning design

- The implementation of the concept made by learning design specifications like PALO, IMS Learning Design,[30] LDL, SLD 2.0, etc...

- The technical realisations around the implementation of the concept like TELOS, RELOAD LD-Author, etc...

Instructional design models

ADDIE process

Perhaps the most common model used for creating instructional materials is the ADDIE Model. This acronym stands for the 5 phases contained in the model.

Brief History of ADDIE’s Development – The ADDIE model was initially developed by FSU to explain “the processes involved in the formulation of an instructional systems development (ISD) program for military interservice training that will adequately train individuals to do a particular job and which can also be applied to any interservice curriculum development activity.”[31] The model contained 19 essential steps that were grouped under its five original phases (Analyze, Design, Develop, Implement, and [Evaluation and] Control)[32], whose completion was expected before movement to the next phase could occur. Over the years, the steps were revised and eventually the model itself became more dynamic and interactive than its original hierarchical rendition, until its most popular version appeared in the mid-80s, as we understand it today.

The five phases are listed and explained below:

Analyze – The first phase of content development begins with Analysis. Analysis refers to the gathering of information about one’s audience, the tasks to be completed, and the project’s overall goals. The instructional designer then classifies the information to make the content more applicable and successful.

Design – The second phase is the Design phase. In this phase, instructional designers begin to create their project. Information gathered from the analysis phase, in conjunction with the theories and models of instructional design, is meant to explain how the learning will be acquired. For example, the design phase begins with writing a learning objective. Tasks are then identified and broken down to be more manageable for the designer. The final step determines the kind of activities required for the audience in order to meet the goals identified in the Analyze phase.

Develop – The third phase, development, relates to the creation of the activities being implemented. This stage is where the blueprints in the design phase are assembled.

Implement – After the content is developed, it is then implemented. This stage allows the instructional designer to test all materials to identify if they are functional and appropriate for the intended audience.

Evaluate – The final phase, evaluate, ensures the materials achieved the desired goals. The evaluation phase consists two parts: formative and summative assessment. Due to the ADDIE model being iterative, each stage of the process incorporates formative assessment. While, the summative assessments contain tests created for the content being implemented. This final phase is vital for the instructional design team because it provides data used to alter and enhance the design[33].

Connecting all phases of the model are external and reciprocal revision opportunities. Aside from the internal Evaluation phase, revisions should and can be made throughout the entire process.

Most of the current instructional design models are variations of the ADDIE process.[34] Dick,W.O,.Carey, L.,&Carey, J.O.(2004)Systematic Design of Instruction. Boston,MA:Allyn&Bacon.

Rapid prototyping

Sometimes utilized adaptation to the ADDIE model is in a practice known as rapid prototyping.

Proponents suggest that through an iterative process the verification of the design documents saves time and money by catching problems while they are still easy to fix. This approach is not novel to the design of instruction, but appears in many design-related domains including software design, architecture, transportation planning, product development, message design, user experience design, etc.[34][35][36] In fact, some proponents of design prototyping assert that a sophisticated understanding of a problem is incomplete without creating and evaluating some type of prototype, regardless of the analysis rigor that may have been applied up front.[37] In other words, up-front analysis is rarely sufficient to allow one to confidently select an instructional model. For this reason many traditional methods of instructional design are beginning to be seen as incomplete, naive, and even counter-productive.[38]

However, some consider rapid prototyping to be a somewhat simplistic type of model. As this argument goes, at the heart of Instructional Design is the analysis phase. After you thoroughly conduct the analysis—you can then choose a model based on your findings. That is the area where most people get snagged—they simply do not do a thorough-enough analysis. (Part of Article By Chris Bressi on LinkedIn)

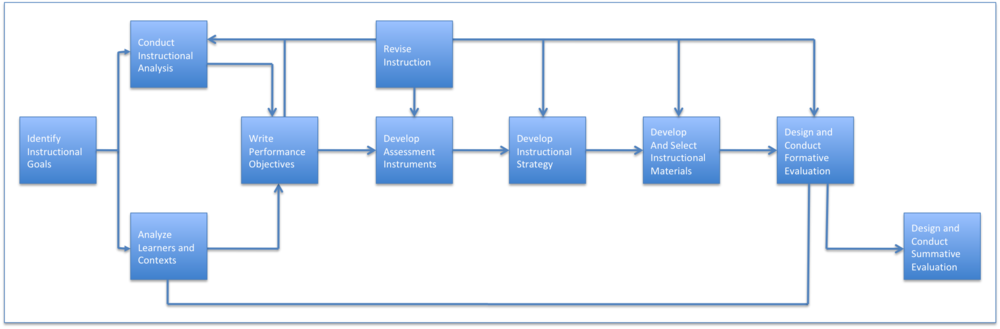

Dick and Carey

Another well-known instructional design model is The Dick and Carey Systems Approach Model.[39] The model was originally published in 1978 by Walter Dick and Lou Carey in their book entitled The Systematic Design of Instruction.

Dick and Carey made a significant contribution to the instructional design field by championing a systems view of instruction as opposed to viewing instruction as a sum of isolated parts. The model addresses instruction as an entire system, focusing on the interrelationship between context, content, learning and instruction. According to Dick and Carey, "Components such as the instructor, learners, materials, instructional activities, delivery system, and learning and performance environments interact with each other and work together to bring about the desired student learning outcomes".[39] The components of the Systems Approach Model, also known as the Dick and Carey Model, are as follows:

- Identify Instructional Goal(s): goal statement describes a skill, knowledge or attitude(SKA) that a learner will be expected to acquire

- Conduct Instructional Analysis: Identify what a learner must recall and identify what learner must be able to do to perform particular task

- Analyze Learners and Contexts: Identify general characteristics of the target audience including prior skills, prior experience, and basic demographics; identify characteristics directly related to the skill to be taught; and perform analysis of the performance and learning settings.

- Write Performance Objectives: Objectives consists of a description of the behavior, the condition and criteria. The component of an objective that describes the criteria that will be used to judge the learner's performance.

- Develop Assessment Instruments: Purpose of entry behavior testing, purpose of pretesting, purpose of posttesting, purpose of practive items/practive problems

- Develop Instructional Strategy: Pre-instructional activities, content presentation, Learner participation, assessment

- Develop and Select Instructional Materials

- Design and Conduct Formative Evaluation of Instruction: Designer try to identify areas of the instructional materials that are in need of improvement.

- Revise Instruction: To identify poor test items and to identify poor instruction

- Design and Conduct Summative Evaluation

With this model, components are executed iteratively and in parallel rather than linearly.[39]

Instructional Development Learning System (IDLS)

Another instructional design model is the Instructional Development Learning System (IDLS).[40] The model was originally published in 1970 by Peter J. Esseff, PhD and Mary Sullivan Esseff, PhD in their book entitled IDLS—Pro Trainer 1: How to Design, Develop, and Validate Instructional Materials.[41]

Peter (1968) & Mary (1972) Esseff both received their doctorates in Educational Technology from the Catholic University of America under the mentorship of Dr. Gabriel Ofiesh, a Founding Father of the Military Model mentioned above. Esseff and Esseff contributed synthesized existing theories to develop their approach to systematic design, "Instructional Development Learning System" (IDLS).

Also see: Managing Learning in High Performance Organizations, by Ruth Stiehl and Barbara Bessey, from The Learning Organization, Corvallis, Oregon. ISBN 0-9637457-0-0.

The components of the IDLS Model are:

- Design a Task Analysis

- Develop Criterion Tests and Performance Measures

- Develop Interactive Instructional Materials

- Validate the Interactive Instructional Materials

Motivational Design

Motivation is defined as an internal drive that activates behavior and gives it direction. The term motivation theory is concerned with the process that describe why and how human behavior is activated and directed.

Motivation Concepts Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation

- Instrinsic: defined as the doing of an activity for its inherent satisfactions rather than for some separable consequence. When intrinsically motivated a person is moved to act for the fun or challenge entailed rather than because of external rewards.[42] Intrinsic motivation reflects the desire to do something because it is enjoyable. If we are intrinsically motivated, we would not be worried about external rewards such as praise.

- Examples: Writing short stories because you enjoy writing them, reading a book because you are curious about the topic, and playing chess because you enjoy effortful thinking

- Extrinsic: reflects the desire to do something because of external rewards such as awards, money and praise. People who are extrinsically motivated may not enjoy certain activities. They may only wish to engage in certain activities because they wish to receive some external reward.[43]

- Examples: The writer who only writes poems to be submitted to poetry contests, a person who dislikes sales but accepts a sales position because he/she desires to earn an above average salary, and a person selecting a major in college based on salary and prestige, rather than personal interest.

John Keller

John Keller has devoted his career to researching and understanding motivation in instructional systems. These decades of work constitute a major contribution to the instructional design field. First, by applying motivation theories systematically to design theory. Second, in developing a unique problem-solving process he calls the ARCS Motivation.

The ARCS Model of Motivational Design

The ARCS Model of Motivational Design was created by John Keller while he was researching was to supplement the learning process with motivation. The model is based on Tolman's and Lewin's expectany-value theory, which presumes that people are motivated to learn if there is value in the knowledge presented (i.e. it fulfills personal needs) and if there is an optimistic expectation for success[44]. The model consists of four main areas : Attention, relevance, Confidence, and Satisfaction.

Attention and relevance according to John Keller's ARCS motivational theory are essential to learning. The first 2 of 4 key components for motivating learners, attention and relevance can be considered the backbone of the ARCS theory, the latter components relying upon the former.

Attention: The attention mentioned in this theory refers to the interest displayed by learners in taking in the concepts/ideas being taught. This component is split into three categories: perceptual arousal, using surprise or uncertain situations; inquiry arousal, offering challenging questions and/or problems to answer/solve; and variability, using a variety of resources and mathods of teaching. Within each of these categorie, John Keller has provided further sub-divisions of types of stimuli to grab attention, which include:

- Perceptual Arousal

- Concreteness- Use specific, relatable examples

- Incongruity and Conflict- Stimulate interest by providing the opposite point of view

- Humor- Use humor to lighten up the subject

- Inquiry Arousal

- Participation- Provide role-play or hands on experience

- Inquiry- Ask questions that get students to do critical thinking or brainstorming

- Variability- Incorporate a variety of teaching methods (video, reading, lecture)

Grabbing attention is the most important part of the model because it initiates the motivation for the learners. Once learners are interested in a topic, they are willing to invest their time, pay attention, and find out more.

Relevance: Relevance, according to Keller, must be established by using language and examples that the learners are familiar with. The three major strategies John Keller presents are goal oriented, motive matching, and familiarity. Like the Attention category, John Keller divided the three major strategies in to subcategories, which provide examples of how to make a lesson plan relevant to the learner:

- Goal Orientation:

- Present Worth- Describe how the knowledge will help the learners today.

- Future Usefulness- Describe how the knowledge will help in the future (getting into college, finding a job, getting a promotion).

- Motive Matching

- Needs Matching- Assess your group and decide whether the learners are learning because of achievement, risk taking, power, or affiliation.

- Choice- Give the learners a choice in what method works best for them when learning something new.

- Familiarity

- Modeling- The concept of "be what you want them to do." Also, bring in role models (people who have used the knowledge that you are presenting to improve their lives).

- Experience- Draws on learner's existing knowledge/skills and shows them how they can use their previous knowledge to learn more.

Learners will throw concepts to the wayside if their attention cannot be grabbed and sustained and if relevance is not conveyed.

Confidence: The confidence aspect of the ARCS model focuses on establishing positive expectations for achieving success among learners. The confidence level of learners is often correlated with motivation and the amount of effort put forth in reaching a performance objective. For this reason, it’s important that learning design provides students with a method for estimating their probability of success. This can be achieved in the form of a syllabus and grading policy, rubrics, or a time estimate to complete tasks. Additionally, confidence is built when positive reinforcement for personal achievements is given through timely, relevant feedback.

John Keller offers learning designers the following confidence building strategies:

- Performance Requirements - Learners should be provided with learning standards and evaluative criteria upfront to establish positive expectations for achieving success. If learners can independently and accurately estimate the amount of effort and time required to achieve success, they are more likely to put forth the required effort. Conversely, if learners are unaware or feel that the learning requirements are out of reach, motivation normally decreases.

- Success Opportunities – Being successful in one learning situation can help to build confidence in subsequent endeavors. Learners should be given the opportunity to achieve success through multiple, varied, and challenging experiences that build upon one another.

- Personal Control- Confidence is increased if a learner attributes their success to personal ability or effort, rather than external factors such as lack of challenge or luck.

Satisfaction: Finally, learners must obtain some type of satisfaction or reward from a learning experience. This satisfaction can be from a sense of achievement, praise from a higher-up, or mere entertainment. Feedback and reinforcement are important elements and when learners appreciate the results, they will be motivated to learn. Satisfaction is based upon motivation, which can be intrinsic or extrinsic. John Keller suggests three main strategies to promote satisfaction:

- Intrinsic Reinforcement – encourage and support intrinsic enjoyment of the learning experience. Example: The teacher invites former students to provide testimonials on how learning these skills helped them with subsequent homework and class projects.

- Extrinsic Rewards – provide positive reinforcement and motivational feedback. Example: The teacher awards certificates to students as they master the complete set of skills.

- Equity – maintain consistent standards and consequences for success. Example: After the term project has been completed, the teacher provides evaluative feedback using the criteria described in class.

To keep learners satisfied, instruction should be designed to allow them to use their newly-learned skills as soon as possible in as authentic a setting as possible.

Other models

Some other useful models of instructional design include: the Smith/Ragan Model[45], the Morrison/Ross/Kemp Model[46] and the OAR Model of instructional design in higher education[47], as well as, Wiggins' theory of backward design.

Learning theories also play an important role in the design of instructional materials. Theories such as behaviorism, constructivism, social learning and cognitivism help shape and define the outcome of instructional materials.

Influential researchers and theorists

This article may contain unverified or indiscriminate information in embedded lists. (December 2010) |

Alphabetic by last name

- Bloom, Benjamin – Taxonomies of the cognitive, affective, and psychomotor domains – 1955

- Bonk, Curtis – Blended learning – 2000s

- Bransford, John D. – How People Learn: Bridging Research and Practice – 1999

- Bruner, Jerome – Constructivism

- Carey, L. – "The Systematic Design of Instruction"

- Clark, Richard – Clark-Kosma "Media vs Methods debate", "Guidance" debate.

- Clark, Ruth – Efficiency in Learning: Evidence-Based Guidelines to Manage Cognitive Load / Guided Instruction / Cognitive Load Theory

- Dick, W. – "The Systematic Design of Instruction"

- Gagné, Robert M. – Nine Events of Instruction (Gagné and Merrill Video Seminar)

- Hannum, Wallace H., Professor, UNC-Chapel Hill – numerous articles and books; search via Google and Google Scholar

- Heinich, Robert – Instructional Media and the new technologies of instruction 3rd ed. – Educational Technology – 1989

- Jonassen, David – problem-solving strategies – 1990s

- Langdon, Danny G – The Instructional Designs Library: 40 Instructional Designs, Educational Tech. Publications

- Mager, Robert F. – ABCD model for instructional objectives – 1962

- Merrill, M. David – Component Display Theory / Knowledge Objects / First Principles of Instruction

- Papert, Seymour – Constructionism, LOGO – 1970s

- Piaget, Jean – Cognitive development – 1960s

- Piskurich, George – Rapid Instructional Design – 2006

- Simonson, Michael – Instructional Systems and Design via Distance Education – 1980s

- Schank, Roger – Constructivist simulations – 1990s

- Sweller, John – Cognitive load, Worked-example effect, Split-attention effect

- Reigeluth, Charles – Elaboration Theory, "Green Books" I, II, and III – 1999–2010

- Skinner, B.F. – Radical Behaviorism, Programed Instruction

- Vygotsky, Lev – Learning as a social activity – 1930s

See also

- ADDIE Model

- educational assessment

- confidence-based learning

- educational animation

- educational psychology

- educational technology

- e-learning

- electronic portfolio

- evaluation

- First Principles of Instruction

- human–computer interaction

- instructional technology

- instructional theory

- interaction design

- learning object

- learning science

- m-learning

- multimedia learning

- online education

- instructional design coordinator

- storyboarding

- training

- interdisciplinary teaching

- rapid prototyping

- lesson study

- Understanding by Design

References

- ^ Merrill, M. D., Drake, L., Lacy, M. J., Pratt, J., & ID2_Research_Group. (1996). Reclaiming instructional design. Educational Technology, 36(5), 5-7. http://mdavidmerrill.com/Papers/Reclaiming.PDF

- ^ Cognition and instruction: Their historic meeting within educational psychology. Mayer, Richard E. Journal of Educational Psychology, Vol 84(4), Dec 1992, 405-412. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.84.4.405 http://psycnet.apa.org/journals/edu/84/4/405/

- ^ Duffy, T. M., & Cunningham, D. J. (1996). Constructivism: Implications for the design and delivery of instruction. In D. Jonassen (Ed.), Handbook of Research for Educational Communications and Technology (pp. 170-198). New York: Simon & Schuster Macmillan

- ^ Duffy, T. M. , & Jonassen, D. H. (1992). Constructivism: New implications for instructional technology. In T. Duffy & D. Jonassen (Eds.), Constructivism and the technology of instruction (pp. 1-16). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- ^ MIL-HDBK-29612/2A Instructional Systems Development/Systems Approach to Training and Education [dead link]

- ^ Bloom's Taxonomy

- ^ Instructional Design Theories. Instructionaldesign.org. Retrieved on 2011-10-07.

- ^ Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. – Educational Psychologist – 38(1):1 – Citation. Leaonline.com (2010-06-08). Retrieved on 2011-10-07.

- ^ Sweller, J. (1988). "Cognitive load during problem solving: Effects on learning". Cognitive Science. 12 (1): 257–285. doi:10.1016/0364-0213(88)90023-7.

- ^ Chandler, P. & Sweller, J. (1991). "Cognitive Load Theory and the Format of Instruction". Cognition and Instruction. 8 (4): 293–332. doi:10.1207/s1532690xci0804_2.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sweller, J., & Cooper, G.A. (1985). "The use of worked examples as a substitute for problem solving in learning algebra". Cognition and Instruction. 2 (1): 59–89. doi:10.1207/s1532690xci0201_3.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cooper, G., & Sweller, J. (1987). "Effects of schema acquisition and rule automation on mathematical problem-solving transfer". Journal of Educational Psychology. 79 (4): 347–362. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.79.4.347.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Mayer, R.E. (1997). "Multimedia Learning: Are We Asking the Right Questions?". Educational Psychologist. 32 (41): 1–19. doi:10.1207/s15326985ep3201_1.

- ^ Mayer, R.E. (2001). Multimedia Learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-78239-2.

- ^ Mayer, R.E., Bove, W. Bryman, A. Mars, R. & Tapangco, L. (1996). "When Less Is More: Meaningful Learning From Visual and Verbal Summaries of Science Textbook Lessons". Journal of Educational Psychology. 88 (1): 64–73. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.88.1.64.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mayer, R.E., Steinhoff, K., Bower, G. and Mars, R. (1995). "A generative theory of textbook design: Using annotated illustrations to foster meaningful learning of science text". Educational Technology Research and Development. 43 (1): 31–41. doi:10.1007/BF02300480.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Paas, F., Renkl, A. & Sweller, J. (2004). "Cognitive Load Theory: Instructional Implications of the Interaction between Information Structures and Cognitive Architecture". Instructional Science. 32: 1–8. doi:10.1023/B:TRUC.0000021806.17516.d0.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Clark, R.C., Mayer, R.E. (2002). e-Learning and the Science of Instruction: Proven Guidelines for Consumers and Designers of Multimedia Learning. San Francisco: Pfeiffer. ISBN 0-7879-6051-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Clark, R.C., Nguyen, F., and Sweller, J. (2006). Efficiency in Learning: Evidence-Based Guidelines to Manage Cognitive Load. San Francisco: Pfeiffer. ISBN 0-7879-7728-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Anglin, G. J., & Towers, R. L. (1992). Reference citations in selected instructional design and technology journals, 1985-1990. Educational Technology Research and DEevelopment, 40, 40-46.

- ^ Perry, J. D. (2001). Learning and cognition. [On-Line]. Available: http://education.indiana.edu/~p540/webcourse/gagne.html

- ^ Driscoll, Marcy P. 2004. Psychology of Learning and Instruction, 3rd Edition. Allyn & Bacon.

- ^ Gagné, R. M. (1985). The conditions of learning (4th ed.). New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

- ^ Gagné, R. M., & Driscoll, M. P. (1988). Essentials of learning for instruction. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- ^ Haines, D. (1996). Gagné. [On-Line]. Available: http://education.indiana.edu/~educp540/haines1.html

- ^ Dowling, L. J. (2001). Robert Gagné and the Conditions of Learning. Walden University.

- ^ Carr-Chellman A. and Duchastel P., "The ideal online course," British Journal of Educational Technology, 31(3), 229–241, July 2000.

- ^ Koper R., "Current Research in Learning Design," Educational Technology & Society, 9 (1), 13–22, 2006.

- ^ Britain S., "A Review of Learning Design: Concept, Specifications and Tools" A report for the JISC E-learning Pedagogy Programme, May 2004.

- ^ IMS Learning Design webpage. Imsglobal.org. Retrieved on 2011-10-07.

- ^ Branson, R. K., Rayner, G. T., Cox, J. L., Furman, J. P., King, F. J., Hannum, W. H. (1975). Interservice procedures for instructional systems development. (5 vols.) (TRADOC Pam 350-30 NAVEDTRA 106A). Ft. Monroe, VA: U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command, August 1975. (NTIS No. ADA 019 486 through ADA 019 490).

- ^ Branson, R. K., Rayner, G. T., Cox, J. L., Furman, J. P., King, F. J., Hannum, W. H. (1975). Interservice procedures for instructional systems development. (5 vols.) (TRADOC Pam 350-30 NAVEDTRA 106A). Ft. Monroe, VA: U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command, August 1975. (NTIS No. ADA 019 486 through ADA 019 490).

- ^ Branson, R. K., Rayner, G. T., Cox, J. L., Furman, J. P., King, F. J., Hannum, W. H. (1975). Interservice procedures for instructional systems development. (5 vols.) (TRADOC Pam 350-30 NAVEDTRA 106A). Ft. Monroe, VA: U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command, August 1975. (NTIS No. ADA 019 486 through ADA 019 490).

- ^ a b Piskurich, G.M. (2006). Rapid Instructional Design: Learning ID fast and right.

- ^ Saettler, P. (1990). The evolution of American educational technology.

- ^ Stolovitch, H.D., & Keeps, E. (1999). Handbook of human performance technology.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kelley, T., & Littman, J. (2005). The ten faces of innovation: IDEO's strategies for beating the devil's advocate & driving creativity throughout your organization. New York: Doubleday.

- ^ Hokanson, B., & Miller, C. (2009). Role-based design: A contemporary framework for innovation and creativity in instructional design. Educational Technology, 49(2), 21–28.

- ^ a b c Dick, Walter, Lou Carey, and James O. Carey (2005) [1978]. The Systematic Design of Instruction (6th ed.). Allyn & Bacon. pp. 1–12. ISBN 0-205-41274-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Esseff, Peter J. and Esseff, Mary Sullivan (1998) [1970]. Instructional Development Learning System (IDLS) (8th ed.). ESF Press. pp. 1–12. ISBN 1-58283-037-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ ESF, Inc. – Train-the-Trainer – ESF ProTrainer Materials – 813.814.1192. Esf-protrainer.com (2007-11-06). Retrieved on 2011-10-07.

- ^ R. Ryan. [www.idealibrary.com "Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations"]. Contemporary Educational Psychology. Retrieved April 1, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Brad Bell. [www.psychologyandsociety.com/motivation.html "Intrinsic Motivation and Extrinsic Motivation with Examples of Each Types of Motivation"]. Blue Fox Communications. Retrieved April 1, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Ely, Donald (1983). Development and Use of the ARCS Model of Motivational Design. Libraries Unlimited. pp. 225–245.

- ^ Smith, P. L. & Ragan, T. J. (2004). Instructional design (3rd Ed.). Danvers, MA: John Wiley & Sons.

- ^ Morrison, G. R., Ross, S. M., & Kemp, J. E. (2001). Designing effective instruction, 3rd ed. New York: John Wiley.

- ^ Joeckel, G., Jeon, T., Gardner, J. (2010). Instructional Challenges In Higher Education: Online Courses Delivered Through A Learning Management System By Subject Matter Experts. In Song, H. (Ed.) Distance Learning Technology, Current Instruction, and the Future of Education: Applications of Today, Practices of Tomorrow. (link to article)

External links

- Instructional Design – An overview of Instructional Design

- ISD Handbook

- Edutech wiki: Instructional design model [1]

- Debby Kalk, Real World Instructional Design Interview