Effective field theory: Difference between revisions

Puzl bustr (talk | contribs) →The renormalization group: More precise subsection wikilink given as parent article is very long |

|||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

==The renormalization group== |

==The renormalization group== |

||

Presently, effective field theories are discussed in the context of the [[renormalization group]] (RG) where the process of ''integrating out'' short distance degrees of freedom is made systematic. Although this method is not sufficiently concrete to allow the actual construction of effective field theories, the gross understanding of their usefulness becomes clear through a RG analysis. This method also lends credence to the main technique of constructing effective field theories, through the analysis of symmetries. If there is a single mass scale '''M''' in the ''microscopic'' theory, then the effective field theory can be seen as an expansion in '''1/M'''. The construction of an effective field theory accurate to some power of '''1/M''' requires a new set of free parameters at each order of the expansion in '''1/M'''. This technique is useful for scattering or other processes where the maximum momentum scale '''k''' satisfies the condition '''k/M≪1'''. Since effective field theories are not valid at small length scales, they need not be [[renormalizable]]. Indeed, the ever expanding number of parameters at each order in '''1/M''' required for an effective field theory means that they are generally not renormalizable in the same sense as [[quantum electrodynamics]] which requires only the renormalization of three parameters. |

Presently, effective field theories are discussed in the context of the [[renormalization group]] (RG) where the process of ''integrating out'' short distance degrees of freedom is made systematic. Although this method is not sufficiently concrete to allow the actual construction of effective field theories, the gross understanding of their usefulness becomes clear through a RG analysis. This method also lends credence to the main technique of constructing effective field theories, through the analysis of symmetries. If there is a single mass scale '''M''' in the ''microscopic'' theory, then the effective field theory can be seen as an expansion in '''1/M'''. The construction of an effective field theory accurate to some power of '''1/M''' requires a new set of free parameters at each order of the expansion in '''1/M'''. This technique is useful for scattering or other processes where the maximum momentum scale '''k''' satisfies the condition '''k/M≪1'''. Since effective field theories are not valid at small length scales, they need not be [[Renormalization#Renormalizability|renormalizable]]. Indeed, the ever expanding number of parameters at each order in '''1/M''' required for an effective field theory means that they are generally not renormalizable in the same sense as [[quantum electrodynamics]] which requires only the renormalization of three parameters. |

||

==Examples of effective field theories== |

==Examples of effective field theories== |

||

Revision as of 15:04, 29 April 2012

| Quantum field theory |

|---|

|

| History |

In physics, an effective field theory is, as any effective theory, an approximate theory, (usually a quantum field theory) that includes appropriate degrees of freedom to describe physical phenomena occurring at a chosen length scale, while ignoring substructure and degrees of freedom at shorter distances (or, equivalently, at higher energies).

The renormalization group

Presently, effective field theories are discussed in the context of the renormalization group (RG) where the process of integrating out short distance degrees of freedom is made systematic. Although this method is not sufficiently concrete to allow the actual construction of effective field theories, the gross understanding of their usefulness becomes clear through a RG analysis. This method also lends credence to the main technique of constructing effective field theories, through the analysis of symmetries. If there is a single mass scale M in the microscopic theory, then the effective field theory can be seen as an expansion in 1/M. The construction of an effective field theory accurate to some power of 1/M requires a new set of free parameters at each order of the expansion in 1/M. This technique is useful for scattering or other processes where the maximum momentum scale k satisfies the condition k/M≪1. Since effective field theories are not valid at small length scales, they need not be renormalizable. Indeed, the ever expanding number of parameters at each order in 1/M required for an effective field theory means that they are generally not renormalizable in the same sense as quantum electrodynamics which requires only the renormalization of three parameters.

Examples of effective field theories

Fermi theory of beta decay

The best-known example of an effective field theory is the Fermi theory of beta decay. This theory was developed during the early study of weak decays of nuclei when only the hadrons and leptons undergoing weak decay were known. The typical reactions studied were:

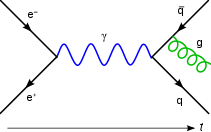

This theory posited a pointlike interaction between the four fermions involved in these reactions. The theory had great phenomenological success and was eventually understood to arise from the gauge theory of electroweak interactions, which forms a part of the standard model of particle physics. In this more fundamental theory, the interactions are mediated by a flavour-changing gauge boson, the W±. The immense success of the Fermi theory was because the W particle has mass of about 80 GeV, whereas the early experiments were all done at an energy scale of less than 10 MeV. Such a separation of scales, by over 3 orders of magnitude, has not been met in any other situation as yet.

BCS theory of superconductivity

Another famous example is the BCS theory of superconductivity. Here the underlying theory is of electrons in a metal interacting with lattice vibrations called phonons. The phonons cause attractive interactions between some electrons, causing them to form Cooper pairs. The length scale of these pairs is much larger than the wavelength of phonons, making it possible to neglect the dynamics of phonons and construct a theory in which two electrons effectively interact at a point. This theory has had remarkable success in describing and predicting the results of experiments.

Other examples

Presently, effective field theories are written for many situations.

- One major branch of nuclear physics is quantum hadrodynamics, where the interactions of hadrons are treated as a field theory, which should be derivable from the underlying theory of quantum chromodynamics. Due to the smaller separation of length scales here, this effective theory has some classificatory power, but not the spectacular success of the Fermi theory.

- In particle physics the effective field theory of QCD called chiral perturbation theory has had better success. This theory deals with the interactions of hadrons with pions or kaons, which are the Goldstone bosons of spontaneous chiral symmetry breaking. The expansion parameter is the pion energy/momentum.

- For hadrons containing one heavy quark (such as the bottom or charm), an effective field theory which expands in powers of the quark mass, called the heavy-quark effective theory (HQET), has been found useful.

- For hadrons containing two heavy quarks, an effective field theory which expands in powers of the relative velocity of the heavy quarks, called non-relativistic QCD (NRQCD), has been found useful, especially when used in conjunctions with lattice QCD.

- For hadron reactions with light energetic (collinear) particles, the interactions with low-energetic (soft) degrees of freedom are described by the soft-collinear effective theory (SCET).

- General relativity is expected to be the low energy effective field theory of a full theory of quantum gravity, such as string theory. The expansion scale is the Planck mass.

- Much of condensed matter physics consists of writing effective field theories for the particular property of matter being studied.

- Effective field theories have also been used to simplify problems in General Relativity (NRGR). In particular in calculating post-Newtonian corrections to the gravity wave signature of inspiralling finite-sized objects. [1]

See also

References and external links

- Effective Field Theory, A. Pich, Lectures at the 1997 Les Houches Summer School "Probing the Standard Model of Particle Interactions."

- Effective field theories, reduction and scientific explanation, by S. Hartmann, Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics 32B, 267-304 (2001).

- On the foundations of chiral perturbation theory, H. Leutwyler (Annals of Physics, v 235, 1994, p 165-203)

- Aspects of heavy quark theory, by I. Bigi, M. Shifman and N. Uraltsev (Annual Reviews of Nuclear and Particle Science, v 47, 1997, p 591-661)

- Effective field theory (Interactions, Symmetry Breaking and Effective Fields - from Quarks to Nuclei. an Internet Lecture by Jacek Dobaczewski)