Coelacanth: Difference between revisions

m Dating maintenance tags: {{Pn}} |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

| image_caption = A preserved specimen of ''Latimeria chalumnae'' in the [[Naturhistorisches Museum|Natural History Museum]], Vienna, Austria (length: 170 cm – weight: 60 kg). This specimen was caught on 18 October 1974, next to Salimani/Selimani (Grand Comoro, Comoro Islands) {{Coord|11|48|40.7|S|43|16|3.3|E}}. |

| image_caption = A preserved specimen of ''Latimeria chalumnae'' in the [[Naturhistorisches Museum|Natural History Museum]], Vienna, Austria (length: 170 cm – weight: 60 kg). This specimen was caught on 18 October 1974, next to Salimani/Selimani (Grand Comoro, Comoro Islands) {{Coord|11|48|40.7|S|43|16|3.3|E}}. |

||

| image_width = 250px |

| image_width = 250px |

||

| status = |

| status = CR |

||

| status_system = |

| status_system = IUCN3.1 |

||

| status_ref = <ref> http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/11375/0 </ref> |

|||

| regnum = [[Animalia]] |

| regnum = [[Animalia]] |

||

| phylum = [[Chordate|Chordata]] |

| phylum = [[Chordate|Chordata]] |

||

Revision as of 16:58, 18 April 2013

| Coelacanth Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| A preserved specimen of Latimeria chalumnae in the Natural History Museum, Vienna, Austria (length: 170 cm – weight: 60 kg). This specimen was caught on 18 October 1974, next to Salimani/Selimani (Grand Comoro, Comoro Islands) 11°48′40.7″S 43°16′3.3″E / 11.811306°S 43.267583°E. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Subclass: | |

| Order: | Coelacanthiformes L. S. Berg, 1937

|

| Species | |

|

West Indian Ocean coelacanth (Latimeria chalumnae) | |

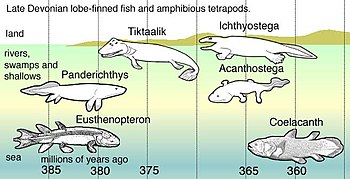

Coelacanth (/[invalid input: 'icon']ˈsiːləkænθ/) is a rare order of fish that includes two extant species: West Indian Ocean coelacanth (Latimeria chalumnae) and the Indonesian coelacanth (Latimeria menadoensis). They follow the oldest known living lineage of Sarcopterygii (lobe-finned fish and tetrapods), which means they are more closely related to lungfish, reptiles and mammals than to the common ray-finned fishes. They are found along the coastlines of the Indian Ocean and Indonesia.[2][3] Since there are only two species of coelacanth and both are threatened, it is the most endangered order of animals in the world. The West Indian Ocean coelacanth is a critically endangered species.

Coelacanths belong to the subclass Actinistia, a group of lobed-finned fish that are related to lungfish and certain extinct Devonian fish such as osteolepiforms, porolepiforms, rhizodonts, and Panderichthys.[4] Coelacanths were thought to have gone extinct in the Late Cretaceous, but were rediscovered in 1938 off the coast of South Africa.[5] Traditionally, the coelacanth was considered a “living fossil” due to its apparent lack of significant evolution over the past millions of years;[4] and the coelacanth was thought to have evolved into roughly its current form approximately 400 million years ago.[6] However, several recent studies have shown that coelacanth body shapes are much more diverse than is generally said.[7][8][9] In addition, it was shown recently that studies concluding that a slow rate of molecular evolution is linked to morphological conservatism in coelacanths are biased by the a priori hypothesis that these species are ‘living fossils’.[10]

Etymology

"Coelacanth" is an adaptation of Modern Latin Cœlacanthus "hollow spine", from Greek κοῖλ-ος koilos "hollow" + ἄκανθ-α akantha "spine", referring to the hollow caudal fin rays of the first fossil specimen described and named by Louis Agassiz in 1839.[4]

Discovery

The coelacanths, which are related to lungfishes and tetrapods, were believed to have been extinct since the end of the Cretaceous period. More closely related to tetrapods than even the ray-finned fish, coelacanths were considered to be transitional species between fish and tetrapods. The first Latimeria specimen was found off the east coast of South Africa, off the Chalumna River (now Tyolomnqa) in 1938.[11] Museum curator Marjorie Courtenay-Latimer discovered the fish among the catch of a local angler, Captain Hendrick Goosen, on December 23, 1938.[11] A local chemistry professor, JLB Smith, confirmed the fish's importance with a famous cable: "MOST IMPORTANT PRESERVE SKELETON AND GILLS = FISH DESCRIBED".[11]

The discovery of a species still living, when they were believed to have gone extinct 65 million years previously, makes the coelacanth the best-known example of a Lazarus taxon, an evolutionary line that seems to have disappeared from the fossil record only to reappear much later. Since 1938, Latimeria chalumnae have been found in the Comoros, Kenya, Tanzania, Mozambique, Madagascar, and in iSimangaliso Wetland Park, Kwazulu-Natal in South Africa.[citation needed]

The second extant species, L. menadoensis, was described from Manado, North Sulawesi, Indonesia in 1999 by Pouyaud et al.[12] based on a specimen discovered by Mark V. Erdmann in 1998[13] and deposited at the Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI). Only a photograph of the first specimen of this species was made at a local market by Erdmann and his wife Arnaz Mehta before it was bought by a shopper.[citation needed]

The coelacanth has no real commercial value, apart from being coveted by museums and private collectors. As a food fish the coelacanth is almost worthless, as its tissues exude oils that give the flesh a foul flavour.[14] The continued survival of the coelacanth may be threatened by commercial deep-sea trawling.[15]

Physical description

Coelacanths are a part of the clade Sarcopterygii, or the lobe-finned fishes. Externally, there are several characteristics that distinguish the coelacanth from other lobe-finned fish. They possess a three-lobed caudal fin, also called a trilobate fin or a diphycercal tail. A secondary tail that goes along and extends past the primary tail separates the upper and lower halves of the coelacanth. Cosmoid scales act as thick armor that protects the exterior of the coelacanth. There also are several internal traits that aid in differentiating coelacanths from other lobe-finned fish. At the back of the skull, the coelacanth possesses a hinge, the intracranial joint, which allows it to open its mouth extremely wide. Coelacanths also retain a notochord, a hollow, pressurized tube which is replaced by the vertebral column early in embryonic development in most other vertebrates. The heart of the coelacanth is shaped differently than most modern fish; the heart's chambers are arranged in a straight tube. The coelacanth braincase is 98.5% filled with fat; only 1.5% of the braincase contains brain tissue. The cheeks of the coelacanths are unique because the opercular bone is very small and holds a large soft-tissue opercular flap. The coelacanth also possesses a unique rostral organ within the ethmoid region of the braincase.[4][16] Also unique to extant coelacanths is the presence of a "fatty lung" or a fat-filled single-lobed vestigial lung.[17]

General description

Latimeria chalumnae and L. menadoensis are the only two known living coelacanth species.[4][18] The word coelacanth literally means, “hollow spine,” because of its unique hollow spine fins.[16] Coelacanths are large, plump, lobe-finned fish that grow up to 1.8 meters. They are nocturnal piscivorous drift-hunters.[19] The body is covered in cosmoid scales that act as armor. Coelacanths have 8 fins – 2 dorsal fins, 2 pectoral fins, 2 pelvic fins, 1 anal fin, and 1 caudal fin. The tail is very nearly equally proportioned and is split by a terminal tuft of fin rays that make up the caudal lobe of the tail. The eyes of the coelacanth are very large, while the mouth is very small. The eye is acclimatized to seeing in poor light by having rods that absorb mostly low wavelengths. The vision of coelacanths has evolved to a mainly blue-shifted color capacity.[20] Pseudomaxillary folds surround the mouth, which replace the maxilla, a structure that is absent in coelacanths. There are two nostrils along with four other external openings that appear between the premaxilla and lateral rostral bones. The nasal sacs resemble those of many other fish and do not contain an internal nostril. The rostral organ of the coelacanth is contained within the ethmoid region of the braincase. It has three unguarded openings into the environment. The rostral organ is used as a part of the coelacanth's laterosensory system.[4] The coelacanth's auditory reception is mediated by its inner ear. The inner ear of the coelacanth is very similar to that of tetrapods because it is classified as being a basilar papilla.[21]

Locomotion of the coelacanths is unique to their kind. To move around, coelacanths most commonly take advantage of up or downwellings of the current and drift. They use their paired fins to stabilize their movement through the water. While on the ocean floor, they do not use their paired fins for any kind of movement. Coelacanths can create thrust for quick starts by using their caudal fins. Due to the high number of fins it possesses, the coelacanth has high maneuverability and can orient its body in almost any direction in the water. They have been seen doing headstands and swimming belly up. It is thought that their rostral organ helps give the coelacanth electroperception, which aids in their movement around obstacles.[19]

Taxonomy

The following is a classification of known coelacanth genera and families:[4][9][18][22][23][24][25]

- Order Coelacanthiformes

- Family Whiteiidae (Triassic)

- Family Rebellatricidae (Triassic)

- Family Coelacanthidae

- Suborder Latimerioidei

- Family Mawsoniidae (Triassic and Jurassic)

- Family Latimeriidae L. S. Berg, 1940

- Holophagus

- Latimeria J. L. B. Smith, 1939

- Latimeria chalumnae J. L. B. Smith, 1939 (West Indian Ocean coelacanth)

- Latimeria menadoensis Pouyaud, Wirjoatmodjo, Rachmatika, Tjakrawidjaja, Hadiaty & Hadie, 1999 (Indonesian coelacanth)

- Libys

- Macropoma

- Macropomoides

- Megacoelacanthus

- Swenzia

- Undina

Fossil record

According to genetic analysis of current species, the divergence of coelacanths, lungfish,and tetrapods is thought to have occurred 390 million years ago.[6] Coelacanths were thought to have undergone extinction 65 million years ago during the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event. The first recorded coelacanth fossil was found in Australia and was of a coelacanth jaw that dated back 360 million years, named Eoachtinistia foreyi. The most recent species of coelacanth in the fossil record is the Macropoma. Macropoma, a sister species to Latimeria chalumnae, is separated by 80 million years. The fossil record of the coelacanth is unique because coelacanth fossils were found 100 years before the first live specimen was identified. In 1938, Courtenay-Latimer rediscovered the first live specimen, L. chalumnae, which was caught off of the coast of East London, South Africa. In 1997, a marine biologist was on a honeymoon and discovered the second live species, Latimeria menadoensis in an Indonesian market. In July 1998, the first live specimen of Latimeria menadoensis was caught in Indonesia. Approximately 80 species of coelacanth have been described, including the two extant species. Before the discovery of a live coelacanth specimen, the coelacanth time range was thought to have spanned from the Middle Devonian to the Upper Cretaceous period. Although fossils found during that time were claimed to demonstrate a similar morphology,[3][4] recent studies pointed out that coelacanth morphological conservatism is a belief that is not based on data.[7][8][9][10]

The following cladogram is based on multiple sources.[9][23][24][25]

Timeline of genera

Geographical distribution

The current coelacanth range remains primarily around the eastern African coast, although the Latimeria menadoensis was discovered off the coast of Indonesia. Coelacanths have been found in the waters of Kenya, Tanzania, Mozambique, South Africa, Madagascar, Comoros, and Indonesia.[3] Most Latimeria chalumnae specimens that have been caught have been captured around the islands of Grande Comore and Anjouan in the Comoros Archipelago, Indian Ocean. Though there have been cases of L. chalumnae being caught elsewhere, amino acid sequencing has shown there is no big difference between these exceptions and the ones found around Comore and Anjouan. Even though these few may be considered strays, there have been several reports of coelacanths being caught off of the coast of Madagascar. This leads scientists to believe that the endemic range of Latimeria chalumnae coelacanths stretches down the eastern coast of Africa from the Comoros Islands, past the western coast of Madagascar, to the South African coastline.[4] The geographical range of the Indonesia coelacanth, Latimeria menadoensis, is believed to be off the coast of Manado Tua Island, Sulawesi, Indonesia in the Celebes Sea.[2] The key components that keep coelacanths in these areas are food and temperature restrictions.[26]

Ecology

During the daytime, coelacanths rest in caves anywhere from 100–500 meters deep while others migrate to deeper waters.[3][4] By resting in cooler waters (below 120 meters) during the daytime, coelacanths reduce metabolic costs. By drifting toward reefs and feeding at night, they save vital energy.[26] Staying in caves during the day also saves energy because they do not have to waste energy fighting the currents.[27]

Because coelacanths hide in caves during the daytime, the Anjouan island and Grande Comore provide ideal habitats for them. The steeply eroded underwater volcanic slopes covered in sand also house an obscure system of caves and crevices, allowing the coelacanths a place to stay during the daylight hours. These crevices support a large benthic fish population that can sustain coelacanth populations.[26][27]

Coelacanths are nocturnal piscivores who feed mainly on benthic fish populations.[26][27] By floating along the lava cliffs, presumably, they feed on whatever fish they encounter.

Coelacanths are fairly peaceful creatures when dealing with other coelacanths. They remain calm, even while in a crowded cave. They do avoid body contact, however, withdrawing immediately if contact is made with another coelacanth. When approached by foreign, potential predators (e.g. a submersible), they react with panic flight reactions. Coelacanths are most likely prey to large deep-water predators. Shark bite marks have been seen on coelacanths and sharks are very common in areas inhabited by coelacanths.[27] Electrophoresis testing of 14 coelacanth enzymes has shown that there is little genetic diversity between coelacanth populations. Among the fish that have been caught, there have been about equal numbers of males and females.[4] Population estimates range from 210 individuals per population, all the way to 500 individuals per population.[4][28] Because coelacanths have individual color markings, scientists think that coelacanths are able to recognize other coelacanths via electric communication.[27]

Life history

Coelacanths are ovoviviparous, meaning that the mother retains the eggs within her body while the embryos develop within them, with a gestation period of more than a year. Typically, the females are larger than the males, and their scales and folds of skin around the cloaca differ. The male coelacanth does not have distinct copulatory organs, just a cloaca. The cloaca has a urogential papilla that is surrounded by erectile caruncles. It is hypothesized that the cloaca turns itself inside out to serve as a copulatory organ.[4][5] The eggs of the coelacanth are very large and have only a thin layer of membrane protecting them. The embryos hatch within the mother and eventually the mother gives live birth. Young coelacanths look very similar to adult coelacanths. The main differences include an external yolk sac, larger eyes relative to their body size, and a more pronounced downward slope of the body. The yolk sac of the juvenile coelacanth is broad and comes out from below the pelvic fins. The scales and the fins of the juvenile coelacanth are completely matured. The young coelacanth does lack odontodes, which it gains during maturation.[5]

Conservation

Because little is known about the coelacanth, the conservation status is difficult to characterize. According to Fricke et al. (1995), there should be some stress put on the importance of conserving this species. From 1988 to 1994, Fricke counted some 60 individuals on each dive. In 1995 that number dropped to 40. Even though this could be a result of natural population fluctuation, it also could be a result of overfishing. Coelacanths usually are caught when local fishermen are fishing for oilfish. Fishermen will sometimes snag a coelacanth instead of an oilfish because they traditionally fish at nighttime when the oilfish (and coelacanths) are feeding. Before scientists became interested in coelacanths, they were thrown back into the water if caught. Now that there is an interest in them, fishermen trade them in to scientists or other officials once they have been caught. Before the 1980s, this was a problem for coelacanth populations. In the 1980s, international aid gave fiberglass boats to the local fishermen, which resulted in fishing out of coelacanth territories into more fish-productive waters. Since then, most of the motors on the boats have broken down so the local fishermen are now back in the coelacanth territory, putting the species at risk again.[4][29]

Different methods to minimize the number of coelacanths caught include moving fishers away from the shore, using different laxatives and malarial salves to reduce the quantity of oilfish needed, using coelacanth models to simulate live specimens, and increasing awareness of the need to protect the species. In 1987 the Coelacanth Conservation Council was established to help protect and encourage population growth of coelacanths.[4]

In 2002, the South African Coelacanth Conservation and Genome Resource Programme was launched to help further the studies and conservation of the coelacanth. The South African Coelacanth Conservation and Genome Resource Programme focuses on biodiversity conservation, evolutionary biology, capacity building, and public understanding. The South African government committed to spending R10 million on the program.[30][31]

Human consumption

Coelacanths are considered a poor source of food for humans and likely most other fish-eating animals. Coelacanth flesh has high amounts of oil, urea, wax esters, and other compounds that are difficult to digest and can cause diarrhea. Where the coelacanth is more common, local fishermen avoid it because of its potential to sicken consumers.[32]

References

- ^ http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/11375/0

- ^ a b Holder, Mark T.; Erdmann, Mark V.; Wilcox, Thomas P.; Caldwell, Roy L.; Hillis, David M. (1999). "Two Living Species of Coelacanths?". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 96 (22): 12616–20. Bibcode:1999PNAS...9612616H. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.22.12616. JSTOR 49396. PMC 23015. PMID 10535971.

- ^ a b c d Butler, Carolyn. "Living Fossil Fish." National Geographic Mar. 2011: 86–93. Print.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Forey, Peter L (1998). History of the Coelacanth Fishes. London: Chapman & Hall. ISBN 978-0-412-78480-4.[page needed]

- ^ a b c Lavett Smith, C.; Rand, Charles S.; Schaeffer, Bobb; Atz, James W. (1975). "Latimeria, the Living Coelacanth, is Ovoviviparous". Science. 190 (4219): 1105–6. Bibcode:1975Sci...190.1105L. doi:10.1126/science.190.4219.1105.

- ^ a b Johanson, Z.; Long, J. A; Talent, J. A; Janvier, P.; Warren, J. W (2006). "Oldest coelacanth, from the Early Devonian of Australia". Biology Letters. 2 (3): 443–6. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2006.0470. PMC 1686207. PMID 17148426.

- ^ a b Friedman, Matt; Coates, Michael I.; Anderson, Philip (2007). "First discovery of a primitive coelacanth fin fills a major gap in the evolution of lobed fins and limbs". Evolution & Development. 9 (4): 329–37. doi:10.1111/j.1525-142X.2007.00169.x. PMID 17651357.

- ^ a b Friedman, Matt; Coates, Michael I. (2006). "A newly recognized fossil coelacanth highlights the early morphological diversification of the clade". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 273 (1583): 245–50. doi:10.1098/rspb.2005.3316. JSTOR 25223279. PMC 1560029. PMID 16555794.

- ^ a b c d Wendruff, Andrew J.; Wilson, Mark V. H. (2012). "A fork-tailed coelacanth,Rebellatrix divaricerca, gen. Et sp. Nov. (Actinistia, Rebellatricidae, fam. Nov.), from the Lower Triassic of Western Canada". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 32 (3): 499–511. doi:10.1080/02724634.2012.657317.

- ^ a b Casane, Didier; Laurenti, Patrick (2013). "Why coelacanths are not 'living fossils'". BioEssays. 35 (4): 332–8. doi:10.1002/bies.201200145. PMID 23382020.

- ^ a b c "'Discovery' of the Coelacanth".

- ^ Pouyaud, Laurent; Wirjoatmodjo, Soetikno; Rachmatika, Ike; Tjakrawidjaja, Agus; Hadiaty, Renny; Hadie, Wartono (1999). "Une nouvelle espèce de cœlacanthe. Preuves génétiques et morphologiques". Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences (in French). 322 (4): 261–7. Bibcode:1999CRASG.322..261P. doi:10.1016/S0764-4469(99)80061-4. PMID 10216801.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Erdmann, Mark V.; Caldwell, Roy L.; Moosa, M. Kasim (1998). "Indonesian 'king of the sea' discovered". Nature. 395 (6700): 335. Bibcode:1998Natur.395..335E. doi:10.1038/26376.

- ^ Piper, Ross (2007). Extraordinary Animals: An Encyclopedia of Curious and Unusual Animals. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-33922-6.[page needed]

- ^ Gilmore, Inigo (7 January 2006). "Dinosaur fish pushed to the brink by deep-sea trawlers". The Observer.

- ^ a b "The Coelacanth – a Morphological Mixed Bag". ReefQuest Centre for Shark Research.

- ^ Brito, Paulo M.; Meunier, François J.; Clément, Gael; Geffard-Kuriyama, Didier (2010). "The histological structure of the calcified lung of the fossil coelacanth Axelrodichthys araripensis (Actinistia: Mawsoniidae)". Palaeontology. 53 (6): 1281–90. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2010.01015.x.

- ^ a b Nelson, Joseph S. (2006). Fishes of the World. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-75644-6.[page needed]

- ^ a b Fricke, Hans; Reinicke, Olaf; Hofer, Heribert; Nachtigall, Werner (1987). "Locomotion of the coelacanth Latimeria chalumnae in its natural environment". Nature. 329 (6137): 331–3. Bibcode:1987Natur.329..331F. doi:10.1038/329331a0.

- ^ Yokoyama, Shozo; Zhang, Huan; Radlwimmer, F. Bernhard; Blow, Nathan S. (1999). "Adaptive Evolution of Color Vision of the Comoran Coelacanth (Latimeria chalumnae)". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 96 (11): 6279–84. Bibcode:1999pnas...96.6279y. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.11.6279. JSTOR 47861. PMC 26872. PMID 10339578.

- ^ Fritzsch, B. (1987). "Inner ear of the coelacanth fish Latimeria has tetrapod affinities". Nature. 327 (6118): 153–4. Bibcode:1987Natur.327..153F. doi:10.1038/327153a0. PMID 22567677.

- ^ Nelson, Joseph S. (2006). Fishes of the World. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 601. ISBN 0-471-25031-7.

- ^ a b Gallo, V., M.S.S. de Carvalho, & H.R.S. Santos (2010). "New occurrence of †Mawsoniidae (Sarcopterygii, Actinistia) in the Morro do Chaves Formation, Lower Cretaceous of the Sergipe-Alagoas Basin, Northeastern Brazil". Boletim do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi. 5 (2): 195–205.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Long, J. A. (1995). The rise of fishes: 500 million years of evolution. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- ^ a b Cloutier, R. & Ahlberg, P. E. (1996). Morphology, characters, and the interrelationships of basal sarcopterygians. pp. 445–479.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Fricke, H., and R. Plante. "Habitat Requirements of the Living Coelacanth Latimeria Chalumnae at Grande Comore, Indian Ocean." Naturwissenschaften 75 (1988): 149–51. Print.

- ^ a b c d e Fricke, Hans, Jürgen Schauer, Karen Hissmann, Lutz Kasang, and Raphael Plante. "CoelacanthLatimeria Chalumnae Aggregates in Caves: First Observations on Their Resting Habitat and Social Behavior." Environmental Biology of Fishes 30.3 (1991): 281–86. Print.

- ^ Hissman, Karen, Hans Fricke, and Jürgen Schauer. "Population Monitoring of the Coelacanth." Conservation Biology 12.4 (1998): 759–65. Print.

- ^ Fricke, H., Hissmann, K., Schauer, J. and Plante, R. (1995) Yet more danger for coelacanths. Nature, London.

- ^ Limson, Janice. "South Africa Announces Plans for Coelacanth Programme." Science in Africa, Africa's First On-Line Science Magazine, Home Page. 2002. Web. 05 Apr. 2011.

- ^ "South African Coelacanth Conservation and Genome Resour..." African Conservation Foundation. Web. 5 Apr. 2011.

- ^ "Know any good recipes for endangered prehistoric fish?" from The Straight Dope

- Sepkoski, Jack (2002). "A compendium of fossil marine animal genera". Bulletins of American Paleontology. 364: p.560. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help)

External links

- Anatomy of the coelacanth by PBS (Adobe Flash required)

- Dinofish.com (requires a frame-capable browser)

- Few pictures SPIEGEL ONLINE

- The African coelacanth genome provides insights into tetrapod evolutionnature.com; 18 April 2013

- 'Living fossil' coelacanth genome sequencedBBC News Science & Environment; 17 April 2013

- IUCN Red List critically endangered species

- Ill-formatted IPAc-en transclusions

- Use dmy dates from October 2010

- Coelacanthiformes

- Latimeriidae

- Living fossils

- Live-bearing fish

- Ovoviviparous fish

- Fauna of Comoros

- Fish of Indonesia

- Fauna of Kenya

- Fauna of Mozambique

- Fish of South Africa

- Fauna of Tanzania

- Lazarus taxa