Yerba mate: Difference between revisions

| Line 124: | Line 124: | ||

* [[Black drink]] |

* [[Black drink]] |

||

* [[Club-Mate]] |

* [[Club-Mate]] |

||

* [[Matte Leão]] |

|||

* ''[[Ilex guayusa]]'' – another caffeine-containing holly, also known as ''guayusa'', is an Amazonian tree of the holly genus, native to the Ecuadorian Amazon rainforest. |

* ''[[Ilex guayusa]]'' – another caffeine-containing holly, also known as ''guayusa'', is an Amazonian tree of the holly genus, native to the Ecuadorian Amazon rainforest. |

||

* [[Ku Ding tea]] – ''Ilex kudingcha'' |

* [[Ku Ding tea]] – ''Ilex kudingcha'' |

||

Revision as of 19:33, 27 April 2013

| Yerba mate, erva mate, mate, or maté | |

|---|---|

| |

| Ilex paraguariensis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| (unranked): | |

| (unranked): | |

| (unranked): | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | I. paraguariensis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Ilex paraguariensis | |

Mate plant, or Yerba mate (Spanish: [ˈʝeɾβa ˈmate]; also spelled in English as maté, from the Spanish: yerba mate, Portuguese: erva-mate [ˈɛʁvɐ ˈmatʃi]), binomial name Ilex paraguariensis, is a species of holly (family Aquifoliaceae), well known as the source of the mate beverage. Though the plant is called yerba in Spanish ("herb" in English), it is a tree and not an herbaceous plant. It is native to subtropical South America in northeastern Argentina, Bolivia, southern Brazil, Uruguay and Paraguay.[1] It was first used and cultivated by the Guaraní people, and also in some Tupí communities in southern Brazil, prior to the European colonization. It was scientifically classified by the Swiss botanist Moses Bertoni, who settled in Paraguay in 1895.

The mate plant, Ilex paraguariensis, is a shrub when young and a tree when adult, growing up to 15 meters tall. The leaves are evergreen, 7–11 cm long and 3–5.5 cm wide, with a serrated margin. The flowers are small, greenish-white, with four petals. The fruit is a red drupe 4–6 mm in diameter. The leaves are often called yerba (Spanish) or erva (Portuguese), both of which mean "herb". They contain caffeine and related compounds and are harvested commercially.

Cultivation

The plant is grown and processed mainly in South America, more specifically in northern Argentina (Corrientes, Misiones), Paraguay, Uruguay and southern Brazil (Rio Grande do Sul, Santa Catarina, Paraná and Mato Grosso do Sul). Cultivators are known as yerbateros (Spanish) or ervamateiros (Brazilian Portuguese).

When the mate is harvested, the branches are dried sometimes with a wood fire, imparting a smoky flavor. Then the leaves and sometimes the twigs are broken up.[citation needed]

The plant Ilex paraguariensis can vary in strength of the flavor, caffeine levels and other nutrients depending on whether it is a male or female plant. Female plants tend to be milder in flavor, and lower in caffeine. They are also relatively scarce in the areas where mate is planted and cultivated, not wild-harvested, compared to the male plants.[2]

According to FAO, Brazil is the biggest producer of mate in the world with 434,727 MT (53%), followed by Argentina with 300,000 MT (37%) and Paraguay with 76,663 MT (10%).[3]

Use as a beverage

The infusion, called mate in Spanish-speaking countries or chimarrão in south Brazil, is prepared by steeping dry leaves (and twigs) of the mate plant in hot water, rather than in boiling water. Drinking mate with friends from a shared hollow gourd (also called a guampa, porongo or mate in Spanish, or cabaça or cuia in Portuguese, or zucca in Italian) with a metal straw (a bombilla in Spanish, bomba in Portuguese) is a common social practice in Uruguay, Argentina and southern Brazil among people of all ages; the beverage is most popular in Uruguay, where people are seen walking on the street carrying the "mate" and "termo" in their arms and where you can find hot water stations to refill the "termo" while on the road, Paraguay, Peru and Chile, eastern Bolivia and other states of Brazil, and has been cultivated in Syria, Lebanon and Jordan.[citation needed] Uruguay is the largest consumer of mate per capita.[citation needed]

The flavor of brewed mate is strongly vegetal, herbal, and grassy, reminiscent of some varieties of green tea. Some consider the flavor to be very agreeable, but it is generally bitter if steeped in boiling water. Flavored mate is also sold, in which the mate leaves are blended with another herb (such as peppermint) or citrus rind.[citation needed]

In Paraguay, Brazil and Argentina, a toasted version of mate, known as mate cocido (Paraguay), chá mate (Brazil) or just mate, is sold in teabag and loose form, and served, sweetened, in specialized shops or on the street, either hot or iced with fruit juice or milk. The same is sold in Uruguay, Argentina and Paraguay in tea bags to be drunk as a tea. In Argentina and southern Brazil, this is commonly drunk for breakfast or in the café for afternoon tea, often with a selection of sweet pastries. It is made by heating mate in water and straining it as it cools.[4]

An iced, sweetened version of toasted mate is sold as an uncarbonated soft drink, with or without fruit flavoring.[5] In Brazil, this cold version of chá mate is specially popular in South and Southeast regions, and can easily be found in retail stores in the same fridge as soft-drinks.[4] The toasted variety of mate has less of a bitter flavor and more of a spicy fragrance. When shaken, it becomes creamy (since the foam formed becomes well mixed throughout the beverage and lasts for some time), known as mate batido. It is more popular in the coastal cities of Brazil, as opposed to the far southern states, where it is consumed in the traditional way (green, drunk with a silver straw from a shared gourd), and called chimarrão. In Argentina, this is called cimarrón.[citation needed]

In Paraguay, western Brazil (Mato Grosso do Sul, west of São Paulo) and the Litoral Argentino, a mate infusion is also drunk as a cold or iced beverage and called tereré or tererê (in Spanish and Portuguese, respectively), usually sucked out of a horn cup called guampa with a bombilla. It could be prepared using cold or iced water (the most common way in Paraguay) or using cold or iced fruit juice (the most common way in Argentina). The "only water" version may be too bitter, but the one prepared using fruit juice is sweetened by the juice itself. Medicinal herbs, known as yuyos, are mixed in a mortar and pestle and added to the water for taste or medicinal reasons. Tereré is consumed in Paraguay and the Litoral (northeast Argentina).[citation needed]

In the Rio de la Plata region, people often consume daily servings of mate. It is common for friends to convene to matear several times a week. In cold weather, the beverage is served hot and in warm weather the hot water is often substituted with lemonade, but not in Uruguay. Children often take mate with lemonade or milk, as well.[citation needed]

As Europeans often meet at a coffee shop, drinking mate is the impetus for gathering with friends in Argentina, southern Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay. Sharing mate is ritualistic and has its own set of rules. Usually, one person, the host or whoever brought the mate, prepares the drink and refills the gourd with water. In these three countries, the hot water can be contained in a vacuum flask, termo (appropriate for drinking mate in the outside) or garrafa térmica (Brazil), or in a pava (kettle), which only can be done at home.[citation needed]

The gourd is passed around, often in a circle, and each person finishes the gourd before giving it back to the brewer. The gourd (also called a mate) is passed in a clockwise order. Since mate can be rebrewed many times, the gourd is passed until the water runs out. When persons no longer want to take mate, they say gracias (thank you) to the brewer when returning the gourd to signify they do not want any more.[citation needed]

During the month of August, Paraguayans have a tradition of mixing mate with crushed leaves, stems, and flowers of the plant known as flor de Agosto[6] (the flower of August, plants of the Senecio genus), which contain pyrrolizidine alkaloids. Modifying mate in this fashion is potentially toxic, as these alkaloids can cause a rare condition of the liver, veno-occlusive disease, which produces liver failure due to progressive occlusion of the small venous channels in the liver.[7]

In South Africa, mate is not well known, but has been introduced to Stellenbosch by a student who sells it nationally. In the tiny hamlet of Groot Marico in the northwest province, mate was introduced to the local tourism office by the returning descendants of the Boers, who in 1902 had emigrated to Patagonia in Argentina after losing the Anglo Boer War. It is also commonly consumed in Syria and other parts of the Middle East.[citation needed]

Chemical composition and properties

Xanthines

Mate contains three xanthines: caffeine, theobromine and theophylline, the main one being caffeine. Caffeine content varies between 0.7% and 1.7% of dry weight[8] (compared with 0.4– 9.3% for tea leaves, 2.5–7.6% in guarana, and up to 3.2% for ground coffee);[9] theobromine content varies from 0.3% to 0.9%; theophylline is present in small quantities, or can be completely absent.[10] A substance previously called "mateine" is a synonym for caffeine (like theine and guaranine).[citation needed]

Preliminary limited studies of mate have shown that the mate xanthine cocktail is different from other plants containing caffeine, most significantly in its effects on muscle tissue, as opposed to those on the central nervous system, which are similar to those of other natural stimulants.[citation needed] The three xanthines present in mate have been shown to have a relaxing effect on smooth muscle tissue, and a stimulating effect on myocardial (heart) tissue.[citation needed]

Mineral content

Mate also contains elements such as potassium, magnesium and manganese.[11]

Health effects

As of 2011 there has not been any double-blind, randomized prospective clinical trial of mate drinking with respect to chronic disease.[12] Some non-blinded studies have found mate consumption to be effective in lipid lowering.[12]

Lipid metabolism

Studies in animals and humans have observed hypocholesterolemic effects of Ilex paraguariensis aqueous extracts. A single-blind controlled trial of 102 volunteers found that after 40 days of drinking 330 mL / day of mate tea (concentration 50g dry leaves / L water), people with already-healthy cholesterol levels experienced an 8.7% reduction in LDL, and hyperlipidemic individuals experienced an 8.6% reduction in LDL and a 4.4% increase in HDL, on average. Participants already on statin therapy saw a 13.1% reduction in LDL and a 6.2% increase in HDL. The authors thus concluded that drinking yerba mate infusions may reduce the risk for cardiovascular diseases.[13]

Cancer

Mate consumption is associated with oral cancer[14] esophagus cancer, cancer of the larynx,[15] and squamous cell of the head and neck.[16][17] The mechanism is believed to be due to the effect of high consumption temperature, rather than due to any innate properties of mate as a beverage.[15]

A study by the International Agency for Research on Cancer showed a limited correlation between oral cancer and the drinking of large quantities of "hot mate".[18] Smaller quantities (less than 1 liter daily) were found to increase risk only slightly, though alcohol and tobacco consumption had a synergistic effect on increasing oral, throat, and esophageal cancer. The study notes the possibility that the increased risk, rather than stemming from the mate itself, could be credited to the high (near-boiling) temperatures at which the mate is consumed in its most traditional way, the chimarrão. The cellular damage caused by thermal stress could lead the esophagus and gastric epithelium to be metaplasic, adapting to the chronic injury. Then, mutations would lead to cellular dysplasia and to cancer.[19] While the IARC study does not specify a specific temperature range for "hot mate", it lists general (not "hot") mate drinking separately, but does not possess the data to assess its effect. It also does not address, in comparison, any effect of consumption temperature with regard to coffee or tea.

Obesity

Few data are available on the effects of yerba mate on weight in humans and further study may be warranted.[20]

Mechanism of action

E-NTPDase activity

Research also shows that mate preparations can alter the concentration of members of the ecto-nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase (E-NTPDase) family, resulting in an elevated level of extracellular ATP, ADP, and AMP. This was found with chronic ingestion (15 days) of an aqueous mate extract, and may lead to a novel mechanism for manipulation of vascular regenerative factors, i.e., treating heart disease.[21]

Antioxidants

In an investigation of mate antioxidant activity, there was a correlation found between content of caffeoyl-derivatives and antioxidant capacity (AOC).[22][23] Amongst a group of Ilex species, Ilex paraguariensis antioxidant activity was the highest.[22]

History

Mate was first consumed by the indigenous Guaraní and also spread in the Tupí people that lived in southern Brazil and Paraguay, and became widespread with the European colonization.[citation needed] In the Spanish colony of Paraguay in the late 16th century, both Spanish settlers and indigenous Guaranís, who had, to some extent, before the Spanish arrival, consumed it.[citation needed] Mate consumption spread in the 17th century to the River Plate and from there to Argentina, Chile, Bolivia and Peru.[citation needed] This widespread consumption turned it into Paraguay's main commodity above other wares, such as tobacco, and Indian labour was used to harvest wild stands.[citation needed]

In the mid 17th century, Jesuits managed to domesticate the plant and establish plantations in their Indian reductions in Misiones, Argentina, sparking severe competition with the Paraguayan harvesters of wild stands.[citation needed] After their expulsion in the 1770s, their plantations fell into decay, as did their domestication secrets.[citation needed] The industry continued to be of prime importance for the Paraguayan economy after independence, but development in benefit of the Paraguayan state halted after the War of the Triple Alliance (1864–1870) that devastated the country both economically and demographically.[citation needed] Some regions with mate plantations in Paraguay became Argentinean territory.[citation needed]

Brazil then became the largest producer of mate.[citation needed] In Brazilian and Argentine projects in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the plant was domesticated once again, opening the way for plantation systems.[citation needed] When Brazilian entrepreneurs turned their attention to coffee in the 1930s, Argentina, which had long been the prime consumer,[24] took over as the largest producer, resurrecting the economy in Misiones Province, where the Jesuits had once had most of their plantations. For years, the status of largest producer shifted between Brazil and Argentina.[24]

Now, Brazil is the largest producer, with 53%, followed by Argentina, 37% and Paraguay, 10%.[3]

There is a Parque Historico do Mate, funded by the State of Parana, Brazil, to educate people on the sustainable harvesting methods needed to maintain the integrity and vitality of the oldest wild forests of mate in the world.[2]

Nomenclature

The name given to the plant in Guaraní, language of the indigenous people who first cultivated and enjoyed mate, is ka'a, which has the same meaning as "herb".[citation needed] Congonha, in Portuguese, is derived from the Tupi expression, meaning something like "what keeps us alive", but a term rarely used nowadays.[citation needed] Mate is from the Quechua mati, meaning "gourd" or the cup made from a gourd.[citation needed] The word Mate is used in both, Portuguese and Spanish languages.[citation needed]

The pronunciation of yerba mate in Spanish is [ˈʝe̞rβ̞ä ˈmäte̞].[citation needed] The accent on the word is on the first syllable, not the second as might be implied by the variant spelling "maté".[citation needed] The word hierba is Spanish for "herb"; yerba is a variant spelling of it which was quite common in Argentina.[citation needed] (Nowadays in Argentina "yerba" refers exclusively to the "yerba mate" plant.[citation needed]) Yerba mate, therefore, originally translated literally as the "gourd herb", i.e. the herb one drinks from a gourd.[citation needed]

The (Brazilian) Portuguese name is either erva-mate [ˈɛʁvɐ ˈmätʃi] (also pronounced [ˈɛrvɐ ˈmäte] or [ˈɛɾvɐ ˈmätɪ] in some regions), the most used term, or rarely "congonha" [kõˈgõ ȷ̃ɐ], from Old Tupi kõ'gõi, which means "what sustains the being".[25] It is also used to prepare the drinks chimarrão (hot), tereré (cold) or chá mate (hot or cold). While the chá mate (tea) is made with the toasted leaves, the other drinks are made with green leaves, and are very popular in the south of the country. Most people colloquially address both the plant and the beverage simply by the word mate.[4]

Both the spellings "mate" and "maté" are used in English, but the latter spelling is never used in Spanish where it means "I killed" as opposed to "gourd".[citation needed] There is no variation of spellings in Spanish.[citation needed] The addition of the acute accent over the final "e" was likely added as a hypercorrection, indicating that the word and its pronunciation are distinct from the common English word "mate".[26][27][28][29][30]

Use as a health food

Mate is consumed as a health food. Packages of yerba mate are available in health food stores and are frequently stocked in the large supermarkets of Europe, Australia and the United States. By 2013, Asian interest in the drink had seen significant growth and led to significant export trade.[31]

See also

- Black drink

- Club-Mate

- Matte Leão

- Ilex guayusa – another caffeine-containing holly, also known as guayusa, is an Amazonian tree of the holly genus, native to the Ecuadorian Amazon rainforest.

- Ku Ding tea – Ilex kudingcha

- Materva (mate soft drink)

- Nativa (beverage)

- Yaupon holly – a caffeine-containing member of the Ilex genus from North America

References

Footnotes

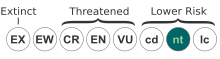

- ^ Template:IUCN2006

- ^ a b "Nativa Yerba Mate". http://www.nativayerbamate.com/harvest.html. Retrieved 2011-07-18.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ a b "FAOSTAT". http://faostat.fao.org/site/339/default.aspx. Retrieved 2011-07-18.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ a b c "Mate: o chá da hora". Retrieved 2012-09-04.

- ^ "Iced Mate Drinks". http://guayaki.com/category/7/Bottled-Yerba-Mate.html. Retrieved 2011-12-21.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ "Flor de agosto".

- ^ McGee, J; Patrick, R S; Wood, C B; Blumgart, L H (1976). "A case of veno-occlusive disease of the liver in Britain associated with herbal tea consumption". Journal of Clinical Pathology. 29 (9): 788–94. doi:10.1136/jcp.29.9.788. PMC 476180. PMID 977780.

- ^ Dellacassa, Cesio et al. Departamento de Farmacognosia, Facultad de Química, Universidad de la República, Uruguay, Noviembre: 2007[page needed]

- ^ "Activities of a Specific Chemical Query". Ars-grin.gov. Retrieved 2011-06-05.

- ^ Vázquez, A; Moyna, P (1986). "Studies on mate drinking". Journal of ethnopharmacology. 18 (3): 267–72. PMID 3821141.

- ^ Valduga, Eunice; de Freitas, Renato João Sossela; Reissmann, Carlos B.; Nakashima, Tomoe (1997). "Caracterização química da folha de Ilex paraguariensis St. Hil. (erva-mate) e de outras espécies utilizadas na adulteração do mate". Boletim do Centro de Pesquisa de Processamento de Alimentos (in Portuguese). 15 (1): 25–36.

- ^ a b Bracesco, N.; Sanchez, A.G.; Contreras, V.; Menini, T.; Gugliucci, A. (2011). "Recent advances on Ilex paraguariensis research: Minireview". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 136 (3): 378–84. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2010.06.032. PMID 20599603.

- ^ De Morais, Elayne C.; Stefanuto, Aliny; Klein, Graziela A.; Boaventura, Brunna C. B.; De Andrade, Fernanda; Wazlawik, Elisabeth; Di Pietro, Patrícia F.; Maraschin, Marcelo; Da Silva, Edson L. (2009). "Consumption of Yerba Mate (Ilex paraguariensis) Improves Serum Lipid Parameters in Healthy Dyslipidemic Subjects and Provides an Additional LDL-Cholesterol Reduction in Individuals on Statin Therapy". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 57 (18): 8316–24. doi:10.1021/jf901660g. PMID 19694438.

- ^ Dasanayake, Ananda P.; Silverman, Amanda J.; Warnakulasuriya, Saman (2010). "Maté drinking and oral and oro-pharyngeal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Oral Oncology. 46 (2): 82–6. doi:10.1016/j.oraloncology.2009.07.006. PMID 20036605.

- ^ a b Loria, Dora; Barrios, Enrique; Zanetti, Roberto (2009). "Cancer and yerba mate consumption: A review of possible associations". Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública. 25 (6): 530. doi:10.1590/S1020-49892009000600010.

- ^ Goldenberg, D; Lee, J; Koch, W; Kim, M; Trink, B; Sidransky, D; Moon, C (2004). "Habitual risk factors for head and neck cancer". Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery. 131 (6): 986–93. doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2004.02.035. PMID 15577802.

- ^ Goldenberg, David; Golz, Avishay; Joachims, Henry Zvi (2003). "The beverage maté: A risk factor for cancer of the head and neck". Head & Neck. 25 (7): 595–601. doi:10.1002/hed.10288.

- ^ International Agency for Research on Cancer (1991). "Summary of Final Evaluations". Coffee, Tea, Mate, Methylxanthines and Methylglyoxal. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. World Health Organization. p. 461. ISBN 978-92-832-1251-5.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Sewram, Vikash; De Stefani, Eduardo; Brennan, Paul; Boffetta, Paolo (2003). "Maté Consumption and the Risk of Squamous Cell Esophageal Cancer in Uruguay". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 12 (6): 508–13. PMID 12814995.

- ^ Pittler, M. H.; Schmidt, K.; Ernst, E. (2005). "Adverse events of herbal food supplements for body weight reduction: Systematic review". Obesity Reviews. 6 (2): 93–111. doi:10.1111/j.1467-789X.2005.00169.x. PMID 15836459.

- ^ Görgen, Milena; Turatti, Kátia; Medeiros, Afonso R.; Buffon, Andréia; Bonan, Carla D.; Sarkis, João J.F.; Pereira, Grace S. (2005). "Aqueous extract of Ilex paraguariensis decreases nucleotide hydrolysis in rat blood serum". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 97 (1): 73–7. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2004.10.015. PMID 15652278.

- ^ a b Filip, Rosana; Lotito, Silvina B.; Ferraro, Graciela; Fraga, Cesar G. (2000). "Antioxidant activity of Ilex paraguariensis and related species". Nutrition Research. 20 (10): 1437–46. doi:10.1016/S0271-5317(00)80024-X.

- ^ Xu, Guang-Hua; Kim, Young-Hee; Choo, Soo-Jin; Ryoo, In-Ja; Yoo, Jae-Kuk; Ahn, Jong-Seog; Yoo, Ick-Dong (2009). "Chemical constituents from the leaves of Ilex paraguariensis inhibit human neutrophil elastase". Archives of Pharmacal Research. 32 (9): 1215–20. doi:10.1007/s12272-009-1905-7. PMID 19784576.

- ^ a b "History of Mate". Establecimiento Las Marías. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- ^ FERREIRA, A. B. H. Novo Dicionário da Língua Portuguesa. Segunda edição. Rio de Janeiro: Nova Fronteira, 1986. p.453

- ^ Webster's Third New International Dictionary of the English Language Unabridged, 2002, shows the main entry for the word as ma·té or ma·te. The explanatory material for main entries on page 14a, headed 1.71, says "When a main entry is followed by the word or and another spelling or form, the two spellings or forms are equal variants. Their order is usually alphabetical, and the first is no more to be preferred than the second..."

- ^ The New Oxford American Dictionary

- ^ The Oxford English Dictionary

- ^ "American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language". Dictionary.reference.com. Retrieved 2011-06-05.

- ^ "Merriam-Webster's Online Dictionary". M-w.com. 2010-08-13. Retrieved 2011-06-05.

- ^ "La yerba mate sigue ganando adeptos en países asiáticos". Territorio Digital (Argentina). 24 January 2013. Retrieved 24 January 2013.

Bibliography

- López, Adalberto. The Economics of Yerba Mate in Seventeenth-Century South America in Agricultural History. Agricultural History Society 1974.