Tohono Oʼodham: Difference between revisions

→Notable Tohono O'odham: lopez |

|||

| Line 65: | Line 65: | ||

In the visual arts, Michael Chiago and the late Leonard Chana have gained widespread recognition for their paintings and drawings of traditional O'odham activities and scenes. Chiago has exhibited at the [[Heard Museum]] and has contributed cover art to ''[[Arizona Highways]]'' magazine and [[University of Arizona]] Press books. Chana illustrated books by Tucson writer Byrd Baylor and created murals for Tohono O'odham Nation buildings. |

In the visual arts, Michael Chiago and the late Leonard Chana have gained widespread recognition for their paintings and drawings of traditional O'odham activities and scenes. Chiago has exhibited at the [[Heard Museum]] and has contributed cover art to ''[[Arizona Highways]]'' magazine and [[University of Arizona]] Press books. Chana illustrated books by Tucson writer Byrd Baylor and created murals for Tohono O'odham Nation buildings. |

||

At the [[National Museum for the American Indian]] (NMAI), the Tohono O'odham were represented in the founding exhibition |

In 2004, the [[Heard Museum]] awarded Danny Lopez its first heritage award, recognizing his lifelong work sustaining the desert people's way of life. At the [[National Museum for the American Indian]] (NMAI), the Tohono O'odham were represented in the founding exhibition and Mr. Lopez blessed the exhibit. |

||

===West Valley Resort=== |

===West Valley Resort=== |

||

Revision as of 18:48, 19 June 2013

Carlos Rios, a Tohono O'Odham headman, photograph by Edward Curtis before 1907 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| United States (Arizona) Mexico (Sonora) | |

| Languages | |

| O'odham, English, Spanish | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity, Traditional | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| other Piman peoples |

The Tohono O'odham are a group of Native American people who reside primarily in the Sonoran Desert of the southeastern Arizona and northwest Mexico. "Tohono O'odham" means "Desert People."

Although they were previously known as the Papago, they have largely rejected this name (meaning literally "tepary-bean eater"), which was applied to them by conquistadores, who had heard them called this by other Piman bands, who are very competitive with the Tohono O'odham. The term Papago derives from Ba:bawĭkoʼa, meaning "eating tepary beans", which was pronounced Papago by the Spanish.

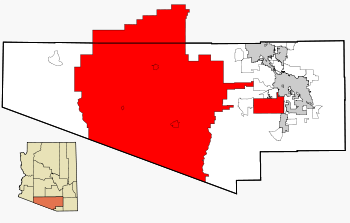

The Tohono O'odham Nation, or Tohono O'odham Indian Reservation, is located in southern Arizona, encompassing portions of Pima County, Pinal County, and Maricopa County.

Administration

A United States reservation residing on a portion of its people's original Sonoran desert lands, the Tohono O'odham Nation within the United States is organized into eleven districts. The land lies in three counties of the state of Arizona: Pima County, Pinal County, and Maricopa County. The main reservation is located between Tucson and Ajo, Arizona, with its administrative center in the town of Sells. A few of the districts are not contiguous with the main reservation: The San Xavier District southwest of Tucson, the San Lucy District near the city of Gila Bend, and the Florence Village near the city of Florence.

The reservation's land area is 11,534.012 square kilometres (4,453.307 sq mi), the third-largest Indian reservation area in the United States (after the Navajo and the Uintah and Ouray). The 2000 census reported 10,787 people living on reservation land. The tribe's enrollment office tallies a population of 25,000, with 20,000 living on its Arizona reservation lands.

The Nation is governed by a council and chairperson, who are elected by eligible adult members of the Nation under a complex formula intended to ensure that the rights of small O'odham communities are protected as well as the interests of the larger communities and families. The present chairman is Ned Norris, Jr. since 2007.

The Nation provides affordable housing through the Tohono O'Odham Ki:Ki Association.

Culture

The Tohono O'odham share linguistic and cultural roots with the closely related Akimel O'odham (People of the River), whose lands lie just south of Phoenix, along the lower Gila River. The Sobaipuri are ancestors to both the Tohono O'odham and the Akimel O'odham who resided along the major rivers of southern Arizona. Ancient pictographs adorn a rock wall that juts up out of the desert near the Baboquivari Mountains.

Debates surround the origins of the O'odham. Claims that the O'odham moved north as recently as 300 years ago compete with claims that the Hohokam, who left the Casa Grande Ruins, are their ancestors. Recent research on the Sobaipuri, now extinct relatives of the O'odham, shows that they were present in sizable numbers in the southern Arizona river valleys in the fifteenth century.

Historically, the O'odham-speaking peoples were at odds with Apaches from the late seventeenth until the beginning of the twentieth centuries when conflict with European settlers caused both the O'odham and the Apaches to reconsider their common interests. It is noteworthy that the O'odham word for the Apache 'enemy' is ob. Still there is considerable evidence that suggests that the O'odham and Apache were friendly and engaged in exchange of goods and marriage partners before the late seventeenth century. O'odham history, however, suggest the constant raids between the two tribes caused the intermarriages, resulting in a mixed tribe of two enemies. Many women and children were taken as slaves between the two tribes, one way a woman could survive in the tribe she was taken into, would be to intermarry and learn the ways and customs of her captors, thus resulting in intermarriage and children of mixed tribal descent.[citation needed]

O'odham musical and dance activities lack "grand ritual paraphernalia that call for attention" and grand ceremonies such as Pow-wows. Instead, they wear muted white clay. O'odham songs are accompanied by hard wood rasps and drumming on overturned baskets, both of which lack resonance and are "swallowed by the desert floor". Dancing features skipping and shuffling quietly in bare feet on dry dirt, the dust raised being believed to rise to atmosphere and assist in forming rain clouds.[2]

The San Xavier District is the location of a major tourist attraction near Tucson, Mission San Xavier del Bac, the "White Dove of the Desert," founded in 1700 by the Jesuit missionary and explorer Eusebio Kino, with the current church building constructed by the Tohono O'odham and Franciscan priests during a period extending from 783 to 1797. It is one of many missions built in the southwest by the Spanish on their then-northern frontier.

The beauty of the mission often leads tourists to presume that the desert people embraced the Catholicism of the Spanish conquistadors. In fact, Tohono O'odham villages had resisted change for hundreds of years. During the 1660s and in 1750s, two major rebellions rivaled in scale the 1680 Pueblo Rebellion. Armed resistance prevented increased Spanish incursions on the lands of Pimería Alta. The Spanish retreated to what they called "Pimería Baja." As a result, much of the desert people's traditions remained largely intact for generations.

It was not until Americans of Anglo-European ancestry began moving into the Arizona territory that traditional ways consistently were oppressed. Indian boarding schools, the cotton industry, and U.S. Federal Indian policy worked hand-in-glove to promote assimilation of these tribe members into the American mainstream. The structure of the current tribal government, established in the 1930s, is a direct result of commercial, missionary, and federal collaboration. The goal was to make the Indians into "real" Americans, yet the boarding schools offered only so much training as was considered necessary for the Indians to work as migrant workers or housekeepers.[3] "Assimilation" was the official policy, but full participation was not the goal. Boarding school students were supposed to function within the segregated society of the United States as economic laborers, not leaders.[4]

Despite a hundred years of being told to and made to change, the Tohono O'odham have retained their traditions into the twenty-first century, and their language is still spoken. Recent decades, however, increasingly have eroded O'odham traditions in the face of the surrounding environment of American mass culture.

The present

Economy

Now numbering more than 25,000 enrolled members, the Tohono O'odham Nation gains most of its income from its three Desert Diamond casinos. This source of income is just over a decade old. It has paid for the tribe's first fire department, but the casinos cannot cover the numerous basic needs of tribal members. Housing, emergency services, medical, and educational needs require expensive infrastructure, including transportation, personnel, education, and technology. The physical isolation of the Nation has always been a handicap to its economic development.

At intervals of approximately two years, the tribal government makes a distribution of excess casino earnings to the adult tribal membership. In the past, this distribution has been $2,000 per adult. In addition, there is a one-time monetary distribution derived from the United States government in satisfaction of treaty obligations with the tribe to each Tohono O'odham upon reaching 18 years of age. This one-time distribution (called "the Thou" from the fact that at one point it was one thousand dollars) presently is $2,000.

Fire fighting

Following the Esperanza Fire (Cabazon, 2006) that resulted in the deaths of five Forest Service employees, several wildland firefighters began to try to locate the family members and written records of former Tribal Member Frank Rios who was killed in a wildfire in October 1967 in the same area, so that his story can be told and remembered, and that his family can be properly honored for their service and their loss. The intent of those firefighters is to make sure his name is shown on the National Fallen Firefighters Memorial, the California Fallen Firefighters Memorial, and that a statue be given to the family on behalf of all wildland firefighters.

Health

Since the 1960s, obesity, and with it, type 2 diabetes have become commonplace among tribal members. Half to three-quarters of all adults are diagnosed with the disease, and about a third of the tribe's adults require regular medical treatment. Federal medical programs have not provided solutions for these problems within the population, and some tribal members have turned to traditional foods and traditional games to control the obesity that often leads to diabetes. Research by Gary Paul Nabhan and others shows that traditional foods regulate blood sugar. A local nonprofit, TOCA, has started a cafe that serves traditional foods.

photograph by Edward Curtis circa 1905

Cultural revitalization

The cultural resources of the Tohono O'odham are threatened—particularly the language—but are stronger than those of many other aboriginal groups in the United States.

Every February, annually, the Sells Rodeo and Parade is held in the capital of the Nation. The rodeo has been an annual event for 73 years. February 2012 was the 74th year the Nation has held the Event.

In the visual arts, Michael Chiago and the late Leonard Chana have gained widespread recognition for their paintings and drawings of traditional O'odham activities and scenes. Chiago has exhibited at the Heard Museum and has contributed cover art to Arizona Highways magazine and University of Arizona Press books. Chana illustrated books by Tucson writer Byrd Baylor and created murals for Tohono O'odham Nation buildings.

In 2004, the Heard Museum awarded Danny Lopez its first heritage award, recognizing his lifelong work sustaining the desert people's way of life. At the National Museum for the American Indian (NMAI), the Tohono O'odham were represented in the founding exhibition and Mr. Lopez blessed the exhibit.

West Valley Resort

In 1960, the Army Corps of Engineers completed construction of the Painted Rock Dam on the Gila River. Flood waters impounded by the dam periodically inundated approximately 10,000 acres (40 km2) of the Tohono O'odham's Gila Bend Reservation. The area lost by the tribe contained a 750-acre (3.0 km2) farm and several communities. Residents were relocated to a 40-acre (160,000 m2) parcel called San Lucy Village, Arizona.[5] In 1986, the federal government and the Nation approved a settlement in which the Nation agreed to give up its legal claims in exchange for $30,000,000 and the right to add replacement land to its Reservation. Public Law 99-503 specifies that the tribe may purchase up to 10,000 acres (40 km2) unincorporated land in Pima, Pinal, or Maricopa counties which the federal government will place into trust, thereby making it legally part of the reservation.[5][6] In 2009, the tribe announced that it had purchased approximately 135 acres (0.55 km2) near Glendale, Arizona, and was planning to construct a shopping center, resort, and casino. The city of Glendale and the Gila River Indian Community opposed the project for various reasons, arguing that it would harm residential neighborhoods and compete with tax-paying businesses.[7] In March 2011, a federal judge dismissed many of the city's claims, including an argument that Public Law 99-503 infringed on the State of Arizona's Sovereignty.[8] Nevertheless, the Resort continues to face multiple legal challenges, including a measure passed by the Arizona Legislature which will allow the city of Glendale to incorporate land owned by the tribe, thereby making the land ineligible for inclusion within the reservation.

Border issues

Most of the 25,000 Tohono O'odham today live in southern Arizona, but there also is a population of several thousand in northern Sonora, Mexico. Unlike aboriginal groups along the U.S.-Canada border, the Tohono O'odham were not given dual citizenship when a border was drawn across their lands in 1853 by the Gadsden Purchase. Even so, members of the nation moved freely across the current international boundary for decades – with the blessing of the U.S. government – to work, participate in religious ceremonies, keep medical appointments in Sells, and visit relatives. Even today, many tribal members make an annual pilgrimage to Magdalena, Sonora, during St. Francis festivities. (Interestingly, the St. Francis festivities in Magdalena are held in the beginning of October (the anniversary of the death of St. Francis of Assisi), and not at the time of St. Francis Xavier, who was a Jesuit). Since the mid-1980s, however, stricter border enforcement has restricted this movement, and tribal members born in Mexico or who have insufficient documentation to prove U.S. birth or residency, have found themselves trapped in a remote corner of Mexico, with no access to the tribal centers only tens of miles away. Since 2001, bills have repeatedly been introduced in Congress to solve the "one people-two country" problem by granting U.S. citizenship to all enrolled members of the Tohono O'odham, but have so far been unsuccessful.[9][10] Reasons that have been advanced in opposition to granting U.S. citizenship to all enrolled members of the Nation include the fact that, for a large part, births on the reservation have been informally recorded and the records are susceptible to easy alteration or falsification.

The proximity of the U.S.-Mexico border incurs further costs to the tribal government and breeds many social problems.

Many of the thousands of people crossing the Sonoran desert to work in U.S. agriculture or to smuggle controlled substances seek emergency assistance from the Tohono O'odham police when they become dehydrated or get stranded. On the ground, border patrol emergency rescue and tribal EMTs coordinate and communicate. The tribe and the state of Arizona pay a large proportion of the bills for border-related law enforcement and emergency services. The former governor of Arizona, Janet Napolitano, (now Secretary of Homeland Security) and Tohono O'odham government leaders have requested repeatedly that the federal government repay the state and the tribe for the costs of border-related emergencies. Tribe Chairman Ned Norris Jr. has complained about the lack of reimbursement for border enforcement.[11]

Kitt Peak

The Tohono O'odham Nation is also the location of the Quinlan and Baboquivari Mountains, which include Kitt Peak and the Kitt Peak National Observatory, and telescopes as well as Baboquivari Peak. The observatory sites are under lease from the Tohono O'odham Nation. The lease was approved by the council in the 1950s, for a one-time payment of $25,000 plus $10 per acre per year.[3] In 2005, the Tohono O'odham Nation brought suit against the National Science Foundation to stop further construction of gamma ray detectors in the Gardens of the Sacred Tohono O'odham Spirit I'itoi, which are just below the summit.

Tohono O'odham Indian Reservation

The Tohono O'odham Indian Reservation, at 32°09′01″N 112°02′41″W / 32.15028°N 112.04472°W, generally is divided into four geographical parts with a total land area of 11,534.012 square kilometres (4,453.307 sq mi) and a 2000 census population of 10,787 persons. The telephone area code for the Tohono O'odham Reservation is 520.

- The main reservation, formerly known as the Papago Indian Reservation, lies in central Pima, southwestern Pinal, and southeastern Maricopa counties, and has a land area of 11,243.098 square kilometres (4,340.984 sq mi) and a 2000 census population of 8,376 persons. The land area is 97.48 percent of the reservation's total, and the population is 77.65 percent of the reservation's total.

- The San Xavier Reservation, at 32°03′00″N 111°05′02″W / 32.05000°N 111.08389°W, is located in Pima County, in the southwestern part of the Tucson metropolitan area. It has a land area of 288.895 square kilometres (111.543 sq mi) and a resident population of 2,053 persons.

- The San Lucy District comprises seven small non-contiguous parcels of land in, and northwest of, the town of Gila Bend in southwestern Maricopa County. Their total land area is 1.915 square kilometres (473 acres), with a total population of 304 persons.

- The Florence Village District is located just southwest of the town of Florence in central Pinal County. It is a single parcel of land with an area of 0.1045 square kilometres (25.8 acres) and a population of 54 persons.

Communities

- Chuichu

- Pisinemo

- Santa Rosa (Kaij Mek)

- Sells

- Topawa

- Kaka

- Kohatk

- Tat Momoli

- Why (part)

Notable Tohono O'odham

- Annie Antone, contemporary, pictorial basketweaver

- Jason David Frank, actor and martial artist

- Terrol Dew Johnson, basketweaver and native food and health advocate

- Augustine Lopez, Tohono O'odham nation chairman

- Ponka-We Victors, Kansas state legislator

- Ofelia Zepeda, linguist and writer

See also

- O'odham language

- Akimel O'odham (River people)

- Hia C-ed O'odham (Sand people)

- List of dwellings of Pueblo peoples

- Chicken scratch

- Shadow Wolves

- Sobaipuri

Sources

- Desert Indian Woman by Frances Manuel and Deborah Neff, University of Arizona Press, Tucson, 2001.

- "In the wake of the wheel: introduction of the wagon to the Papago Indians of southern Arizona." by Wesley Bliss. Pp. 23–33 in Human Problems in Technological Change, edited by E.H. Spicer. New York: Russell Sage Foundation Publications.

- The Tohono O'odham and Pimeria Alta by Allan J. McIntyre, Arcadia Publishing, 2008.

- A Syndetic Approach to Identification of the Historic Mission Site of San Cayetano Del Tumacácori, by Deni J. Seymour, 2007a, in International Journal of Historical Archaeology, 11(3):269–296.

- Delicate Diplomacy on a Restless Frontier: Seventeenth-Century Sobaipuri Social And Economic Relations in Northwestern New Spain, Part I, by Deni J. Seymour, 2007b, in New Mexico Historical Review, 82(4).

- Delicate Diplomacy on a Restless Frontier: Seventeenth-Century Sobaipuri Social And Economic Relations in Northwestern New Spain, Part II, Deni J. Seymour, 2008, in New Mexico Historical Review, 83(2).

- Tohono O'odham Reservation and Off-Reservation Trust Land, Arizona United States Census Bureau.

- Papago Park: A History of Hole-in-the-Rock from 1848 to 1995, Pueblo Grande Museum Occasional Papers No. 1, by Jason H. Gart, 1997

References

- ^ American Indian, Alaska Native Tables from the Statistical Abstract of the United States: 2004–2005

- ^ Zepeda, Ofelia (1995). Ocean Power: Poems from the Desert, p.89. ISBN 0-8165-1541-7.

- ^ Banks, Dennis & Yuri Morita (1993).Seinaru Tamashii: Gendai American Indian Shidousha no Hansei, Japan, Asahi Bunko.

- ^ by official internet site of "the American Indian Heritage Support Center"

- ^ a b ISSUE BRIEF: THE UNITED STATES’ OBLIGATION TO REPLACE DAMAGED RESERVATION LAND

- ^ Monica Alonzo, Wanna Bet? The Tohono O'odham Want to Build a Casino in the West Valley – Now It's Up to the Feds to Make It Happen or Break Another Promise to the Tribe, Phoenix New Times, Apr. 29 2010, available at http://www.phoenixnewtimes.com/2010-04-29/news/wanna-bet-the-tohono-o-odham-want-to-build-a-casino-in-the-west-valley-now-it-s-up-to-the-feds-to-make-it-happen-or-break-another-promise-to-the-tribe/

- ^ City of Glendale Official Website, http://www.glendaleaz.com/indianreservation/

- ^ O'odham closer to casino by Glendale, Arizona Daily Star, Mar 4. 2011, available at http://azstarnet.com/news/local/article_9c4bec3e-a9f6-5030-ac06-753464ee0507.html

- ^ Duarte, Carmen. "Nation Divided." Arizona Daily Star 30 May 14 February 2001 2007 [1]

- ^ Grijalva, Raul M.. United States. Subcommittee on Immigration, Border Security, and Claims. H.R.731. Washington, D.C.: GPO, 2003. [2]

- ^ McCombs, Brady (2007-08-19). "O'odham leader vows no border fence". Arizona Daily Star. Retrieved 2011-04-11.

External links

- Official Website of the Tohono O'odham Nation

- Tohono O'odham / ITCA (Inter Tribal Council of Arizona)

- Tohono O'odham Community Action (TOCA)

- TOCA's Desert Rain Cafe

- How To Speak Tohono O'odham – Video

- Tohono O'odham utilities

- O'odham Solidarity Project

- Online Tohono O'odham bibliography

- Tohono O'odham, Papago in Sonora, Mexico