Ball lightning: Difference between revisions

Tagging 2 dead links using Checklinks & Adding access dates |

→Direct measurements of natural ball lightning: mention location of experiment |

||

| Line 121: | Line 121: | ||

== Direct measurements of natural ball lightning == |

== Direct measurements of natural ball lightning == |

||

[[File:Ball lightning spectrum.svg|thumb|upright=1.4|alt=Emission spectrum of ball lighning|The emission spectrum (intensity vs. wavelength) of a natural ball lightning]] |

[[File:Ball lightning spectrum.svg|thumb|upright=1.4|alt=Emission spectrum of ball lighning|The emission spectrum (intensity vs. wavelength) of a natural ball lightning]] |

||

In January 2014, scientists from [[Northwest Normal University]] in [[Lanzhou]], [[China]], published the results of recordings made in July 2012 of the optical spectrum of what was thought to be natural ball lightning made during the study of ordinary cloud–ground [[ |

In January 2014, scientists from [[Northwest Normal University]] in [[Lanzhou]], [[China]], published the results of recordings made in July 2012 of the optical spectrum of what was thought to be natural ball lightning made during the study of ordinary cloud–ground lightning on China's [[Qinghai Plateau]].<ref name="BLspectrum"/><ref name="BLspectrumvideo">{{cite web|url=http://physics.aps.org/articles/v7/5|title=Focus: First Spectrum of Ball Lightning|last1=Ball|first1=Philip|authorlink1=Philip Ball|date=17 January 2014|work=Focus|publisher=[[American Physical Society]]|accessdate=19 January 2014|doi=10.1103/Physics.7.5}}</ref> At a distance of {{convert|900|m|ft|abbr=on}}, a total of 1.64 seconds of digital video of the ball lightning and its spectrum was made, from the formation of the ball lightning after the ordinary lightning struck the ground, up to the optical decay of the phenomenon. Additional video was recorded by a high-speed (3000 frames/sec) camera, which captured only the last 0.78 seconds of the event, due to its limited recording capacity. They detected [[emission line]]s of neutral atomic [[silicon]], [[calcium]], [[iron]], [[nitrogen]] and [[oxygen]]—in contrast with mainly ionized nitrogen emission lines in the spectrum of the parent lightning. The ball lightning traveled horizontally across the video frame at an average speed equivalent of 8.6{{nbsp}}m/s. |

||

Oscillations in the light intensity and in the oxygen and nitrogen emission at a frequency of 100 [[Hz]], possibly caused by the electric field of the 50 Hz high-voltage power transmission line in the vicinity, were observed. From the spectrum, the temperature of the ball lightning was assessed as being lower than the temperature of the parent lightning (<15,000–30,000 [[Kelvin|K]]). The observed data are consistent with vaporization of soil as well as with ball lightning's sensitivity to [[electric field]]s.<ref name="BLspectrum"/><ref name="BLspectrumvideo"/> |

Oscillations in the light intensity and in the oxygen and nitrogen emission at a frequency of 100 [[Hz]], possibly caused by the electric field of the 50 Hz high-voltage power transmission line in the vicinity, were observed. From the spectrum, the temperature of the ball lightning was assessed as being lower than the temperature of the parent lightning (<15,000–30,000 [[Kelvin|K]]). The observed data are consistent with vaporization of soil as well as with ball lightning's sensitivity to [[electric field]]s.<ref name="BLspectrum"/><ref name="BLspectrumvideo"/> |

||

Revision as of 23:28, 22 January 2014

Ball lightning is an unexplained atmospheric electrical phenomenon. The term refers to reports of luminous, usually spherical objects, which vary from pea-sized to several meters in diameter. It is usually associated with thunderstorms, but lasts considerably longer than the split-second flash of a lightning bolt. Many early reports say that the ball eventually explodes, sometimes with fatal consequences, leaving behind the odor of sulfur.[1][2]

Until the 1960s, most scientists argued that ball lightning was not a real phenomenon, despite numerous sightings throughout the world.[3] Laboratory experiments can produce effects that are visually similar to reports of ball lightning, but whether these are related to the natural phenomenon remains unclear.

Scientific data on natural ball lightning are scarce, owing to its infrequency and unpredictability. The presumption of its existence is based on reported public sightings, and has therefore produced somewhat inconsistent findings. Given inconsistencies and lack of reliable data, the true nature of ball lightning is still unknown.[4] The first ever optical spectrum of what appears to have been a ball lightning event was published in January 2014 and included a video at high frame rate and spectrograph data.[5][6]

Historical accounts

It has been suggested that ball lightning could be the source of the legends that describe luminous balls, such as the Mapuche Anchimayen of mythology (of southern Argentina and Chile).

In a 1960 study, 5% of the population of the Earth reported having witnessed ball lightning.[7][8] Another study analyzed reports of 10,000 cases.[7][9]

M. l'abbé de Tressan, in Mythology compared with history: or, the fables of the ancients elucidated from historical records:

... during a storm which endangered the ship Argo, fires were seen to play round the heads of the Tyndarides, and the instant after the storm ceased. From that time, those fires which frequently appear on the surface of the ocean were called the fire of Castor and Pollux. When two were seen at the same time, it announced the return of calm; when only one, it was the presage of a dreadful storm. This species of fire is frequently seen by sailors, and is a species of ignis fatuus. (page 417)

This account, however, shares more commonalities with the St. Elmo's fire phenomenon.

Wells, Somerset

It was reported In John Stowe's Annals that in December 1596 during a church sermon at Wells in Somerset, England;

There entered in at the west window of the church a dark unproportioned thing about the bigness of a football, and went along the wall on the pulpit side; and suddenly it seemed to break with no less sound than if a hundred cannons had been discharged at once; and therewithal came a most violent storm and tempest of lightning and thunder as if the church had been full of fire.

No-one was killed, though many (including the preacher) were thrown to the ground. Many were "marked in their garments with figures of crosses and stars." Some of the stonework broke down, and the wires and irons in the clock melted, but none of the woodwork was burned.[10]

The Great Thunderstorm of Widecombe-in-the-Moor

Another early description was reported during the Great Thunderstorm at a church in Widecombe-in-the-Moor, Devon, in England, on 21 October 1638. Four people died and approximately 60 were injured when, during a severe storm, an 8-foot (2.4 m) ball of fire was described as striking and entering the church, having nearly destroyed it. Large stones from the church walls were hurled into the ground and through large wooden beams. The ball of fire allegedly smashed the pews and many windows, and filled the church with a foul sulfurous odour and dark, thick smoke.

The ball of fire reportedly divided into two segments, one exiting through a window by smashing it open, the other disappearing somewhere inside the church. The explanation at the time, because of the fire and sulfur smell, was that the ball of fire was "the devil" or the "flames of hell". Later, some blamed the entire incident on two people who had been playing cards in the pew during the sermon, thereby incurring God's wrath.[1]

The Catherine and Mary

In December 1726 a number of British newspapers printed an extract of a letter from John Howell of the sloop Catherine and Mary:

As we were coming thro’ the Gulf of Florida on the 29th of August, a large ball of fire fell from the Element and split our mast in Ten Thousand Pieces, if it were possible; split our Main Beam, also Three Planks of the Side, Under Water, and Three of the Deck; killed one man, another had his Hand carried of [sic], and had it not been for the violent rains, our Sails would have been of a Blast of Fire.[11][12]

The Montague

One particularly large example was reported "on the authority of Dr. Gregory" in 1749:

Admiral Chambers on board the Montague, 4 November 1749, was taking an observation just before noon...he observed a large ball of blue fire about three miles distant from them. They immediately lowered their topsails, but it came up so fast upon them, that, before they could raise the main tack, they observed the ball rise almost perpendicularly, and not above forty or fifty yards from the main chains when it went off with an explosion, as great as if a hundred cannons had been discharged at the same time, leaving behind it a strong sulphurous smell. By this explosion the main top-mast was shattered into pieces and the main mast went down to the keel.

Five men were knocked down and one of them much bruised. Just before the explosion, the ball seemed to be the size of a large mill-stone.[2]

Georg Richmann

A 1753 report depicts ball lightning as being lethal when Professor Georg Richmann of Saint Petersburg, Russia, created a kite-flying apparatus similar to Benjamin Franklin's proposal a year earlier. Richmann was attending a meeting of the Academy of Sciences when he heard thunder and ran home with his engraver to capture the event for posterity. While the experiment was under way, ball lightning appeared and travelled down the string, struck Richmann's forehead and killed him. The ball left a red spot on Richmann's forehead, his shoes were blown open, and his clothing was singed. His engraver was knocked unconscious. The door frame of the room was split and the door was torn from its hinges.[13]

HMS Warren Hastings

An English journal reported that during an 1809 storm, three "balls of fire" appeared and "attacked" the British ship HMS Warren Hastings. The crew watched one ball descend, killing a man on deck and setting the main mast on fire. A crewman went out to retrieve the fallen body and was struck by a second ball, which knocked him back and left him with mild burns. A third man was killed by contact with the third ball. Crew members reported a persistent, sickening sulfur smell afterward.[14][15]

Ebenezer Cobham Brewer

Ebenezer Cobham Brewer, in his 1864 US edition of A Guide to the Scientific Knowledge of Things Familiar, discussed "globular lightning". He describes it as slow-moving balls of fire or explosive gas that sometimes fall to the earth or run along the ground during a thunderstorm. He said that the balls sometimes split into smaller balls and may explode "like a cannon".[16]

Wilfrid de Fonvielle

In his book Thunder and Lighting,[17] translated into English in 1875, French science writer Wilfrid de Fonvielle wrote that there had been about 150 reports of globular lightning:

Globular lighting seems to be particularly attracted to metals; thus it will seek the railings of balconies, or else water or gas pipes etc, It has no peculiar tint of its own but will appear of any colour as the case may be ... at Coethen in the Duchy of Anhalt it appeared green. M. Colon, Vice-President of the Geological Society of Paris, saw a ball of lightning descend slowly from the sky along the bark of a poplar tree; as soon as it touched the earth it bounced up again, and disappeared without exploding. On 10th of September 1845 a ball of lightning entered the kitchen of a house in the village of Salagnac in the valley of Correze. This ball rolled across without doing any harm to two women and a young man who were here; but on getting into an adjoining stable it exploded and killed a pig which happened to be shut up there, and which, knowing nothing about the wonders of thunder and lightning, dared to smell it in the most rude and unbecoming manner.

The motion of such balls is far from being very rapid – they have even been observed occasionally to pause in their course, but they are not the less destructive for all that. A ball of lightning which entered the church of Stralsund, on exploding, projected a number of balls which exploded in their turn like shells.[18]

Tsar Nicholas II

Tsar Nicholas II, the last Emperor of Russia, reported witnessing what he called "a fiery ball" while in the company of his grandfather, Tsar Alexander II: "Once my parents were away," recounted the Tsar, "and I was at the all-night vigil with my grandfather in the small church in Alexandria. During the service there was a powerful thunderstorm, streaks of lightning flashed one after the other, and it seemed as if the peals of thunder would shake even the church and the whole world to its foundations. Suddenly it became quite dark, a blast of wind from the open door blew out the flame of the candles which were lit in front of the iconostasis, there was a long clap of thunder, louder than before, and I suddenly saw a fiery ball flying from the window straight towards the head of the Emperor. The ball (it was of lightning) whirled around the floor, then passed the chandelier and flew out through the door into the park. My heart froze, I glanced at my grandfather – his face was completely calm. He crossed himself just as calmly as he had when the fiery ball had flown near us, and I felt that it was unseemly and not courageous to be frightened as I was. I felt that one had only to look at what was happening and believe in the mercy of God, as he, my grandfather, did. After the ball had passed through the whole church, and suddenly gone out through the door, I again looked at my grandfather. A faint smile was on his face, and he nodded his head at me. My panic disappeared, and from that time I had no more fear of storms."[19]

Aleister Crowley

British occultist Aleister Crowley reported witnessing what he referred to as "globular electricity" during a thunderstorm on Lake Pasquaney[20] in New Hampshire in 1916. He was sheltered in a small cottage when he "noticed, with what I can only describe as calm amazement, that a dazzling globe of electric fire, apparently between six and twelve inches (15–30 cm) in diameter, was stationary about six inches below and to the right of my right knee. As I looked at it, it exploded with a sharp report quite impossible to confuse with the continuous turmoil of the lightning, thunder and hail, or that of the lashed water and smashed wood which was creating a pandemonium outside the cottage. I felt a very slight shock in the middle of my right hand, which was closer to the globe than any other part of my body."[21]

R.C. Jennison

Jennison, of the Electronics Laboratory at the University of Kent, described his own observation of ball lightning:

I was seated near the front of the passenger cabin of an all-metal airliner (Eastern Airlines Flight EA 539) on a late night flight from New York to Washington. The aircraft encountered an electrical storm during which it was enveloped in a sudden bright and loud electrical discharge (0005 h EST, March 19, 1963). Some seconds after this a glowing sphere a little more than 20 cm in diameter emerged from the pilot's cabin and passed down the aisle of the aircraft approximately 50 cm from me, maintaining the same height and course for the whole distance over which it could be observed.[22]

Other accounts

- On 30 April 1877, a ball of lightning entered the Golden Temple at Amritsar, India, and exited through a side door. Several people observed the ball, and the incident is inscribed on the front wall of Darshani Deodhi.[23]

- On 22 November 1894, an unusually prolonged instance of natural ball lightning occurred in Golden, Colorado, which suggests it could be artificially induced from the atmosphere. The Golden Globe newspaper reported, "A beautiful yet strange phenomenon was seen in this city on last Monday night. The wind was high and the air seemed to be full of electricity. In front of, above and around the new Hall of Engineering of the School of Mines, balls of fire played tag for half an hour, to the wonder and amazement of all who saw the display. In this building is situated the dynamos and electrical apparatus of perhaps the finest electrical plant of its size in the state. There was probably a visiting delegation from the clouds, to the captives of the dynamos on last Monday night, and they certainly had a fine visit and a roystering game of romp."[24]

- In July 1907 the Cape Naturaliste Lighthouse in Western Australia was hit by ball lightning. Lighthouse keeper Patrick Baird was in the tower at the time and was knocked unconscious. His daughter Ethel recorded the event.[25]

- An early fictional reference to ball lightning appears in a children's book set in the 19th century by Laura Ingalls Wilder.[26] The books are considered historical fiction, but the author always insisted they were descriptive of actual events in her life. In Wilder's description, three separate balls of lightning appear during a winter blizzard near a cast iron stove in the family's kitchen. They are described as appearing near the stovepipe, then rolling across the floor, only to disappear as the mother (Caroline Ingalls) chases them with a willow-branch broom.[27]

- Pilots in World War II described an unusual phenomenon for which ball lightning has been suggested as an explanation. The pilots saw small balls of light moving in strange trajectories, which came to be referred to as foo fighters.

- Submariners in WWII gave the most frequent and consistent accounts of small ball lightning in the confined submarine atmosphere. There are repeated accounts of inadvertent production of floating explosive balls when the battery banks were switched in or out, especially if mis-switched or when the highly inductive electrical motors were mis-connected or disconnected. An attempt later to duplicate those balls with a surplus submarine battery resulted in several failures and an explosion.[28]

- On 6 August 1944, a ball of lightning went through a closed window in Uppsala, Sweden, leaving a circular hole about 5 cm in diameter. The incident was witnessed by residents in the area, and was recorded by a lightning strike tracking system[29] on the Division for Electricity and Lightning Research at Uppsala University.[30]

- In 1954 Domokos Tar, a physicist, observed a lightning strike during a heavy thunderstorm.[31][32] A single bush was flattened in the wind. Some seconds later a speedy rotating ring (cylinder) appeared in the shape of a wreath. The ring was about 5 m away from the lightning impact point. The ring's plane was perpendicular to the ground and in full view of the observer. The outer/inner diameters were about 60/30 cm. The ring rotated quickly about 80 cm above the ground. It was composed of wet leaves and dirt and rotated counter clockwise. After seconds the ring became self-illuminated turning increasingly red, then orange, yellow and finally white. The ring (cylinder) at the outside was similar to a sparkler.[33] In spite of the rain, many electrical high voltage discharges could be seen.[34] After some seconds, the ring suddenly disappeared and simultaneously the ball lightning appeared in the middle. Initially the ball had only one tail and it rotated in the same direction as the ring. It was homogenous and showed no transparency. In the first moment the ball hovered motionless, but then began to move forward on the same line with a constant speed of about 1 m/s. It was stable and travelled at the same height in spite of the heavy rain and strong wind. After moving about 10 m it suddenly disappeared without any noise.

- On 10 July 2011, during a powerful thunderstorm, a ball of light with a two-metre tail went through a window to the control room of local emergency services in Liberec, Czech Republic. The ball bounced from window to the ceiling, then to the floor and back to the ceiling, where it rolled along it for two or three metres. Then it dropped to the floor and disappeared. The staff present in the control room were frightened, smelled electricity and burned cables and thought something was burning. The computers froze (not crashed) and all communications equipment was knocked out for the night until restored by technicians. Aside from damages caused by disrupting equipment, only one computer monitor was destroyed.[35]

Characteristics

Descriptions of ball lightning vary widely. It has been described as moving up and down, sideways or in unpredictable trajectories, hovering and moving with or against the wind; attracted to,[36] unaffected by, or repelled from buildings, people, cars and other objects. Some accounts describe it as moving through solid masses of wood or metal without effect, while others describe it as destructive and melting or burning those substances. Its appearance has also been linked to power lines[37] as well as during thunderstorms and also calm weather. Ball lightning has been described as transparent, translucent, multicolored, evenly lit, radiating flames, filaments or sparks, with shapes that vary between spheres, ovals, tear-drops, rods, or disks.[38]

Ball lightning is often erroneously identified as St. Elmo's fire. They are separate and distinct phenomena.[39]

The balls have been reported to disperse in many different ways, such as suddenly vanishing, gradually dissipating, absorption into an object, "popping," exploding loudly, or even exploding with force, which is sometimes reported as damaging. Accounts also vary on their alleged danger to humans, from lethal to harmless.

A review of the available literature published in 1972[40] identified the properties of a “typical” ball lightning, whilst cautioning against over-reliance on eye-witness accounts:

- They frequently appear almost simultaneously with cloud-to-ground lightning discharge

- They are generally spherical or pear-shaped with fuzzy edges

- Their diameters range from 1–100 cm, most commonly 10–20 cm

- Their brightness corresponds to roughly that of a domestic lamp, so they can be seen clearly in daylight

- A wide range of colours has been observed, red, orange, and yellow being the most common.

- The lifetime of each event is from 1 second to over a minute with the brightness remaining fairly constant during that time

- They tend to move, most often in a horizontal direction at a few metres per second, but may also move vertically, remain stationary or wander erratically.

- Many are described as having rotational motion

- It is rare that observers report the sensation of heat, although in some cases the disappearance of the ball is accompanied by the liberation of heat

- Some display an affinity for metal objects and may move along conductors such as wires or metal fences

- Some appear within buildings passing through closed doors and windows

- Some have appeared within metal aircraft and have entered and left without causing damage

- The disappearance of a ball is generally rapid and may be either silent or explosive

- Odors resembling ozone, burning sulfur, or nitrogen oxides are often reported

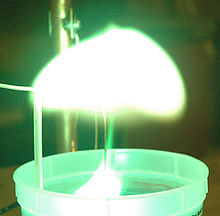

Direct measurements of natural ball lightning

In January 2014, scientists from Northwest Normal University in Lanzhou, China, published the results of recordings made in July 2012 of the optical spectrum of what was thought to be natural ball lightning made during the study of ordinary cloud–ground lightning on China's Qinghai Plateau.[5][41] At a distance of 900 m (3,000 ft), a total of 1.64 seconds of digital video of the ball lightning and its spectrum was made, from the formation of the ball lightning after the ordinary lightning struck the ground, up to the optical decay of the phenomenon. Additional video was recorded by a high-speed (3000 frames/sec) camera, which captured only the last 0.78 seconds of the event, due to its limited recording capacity. They detected emission lines of neutral atomic silicon, calcium, iron, nitrogen and oxygen—in contrast with mainly ionized nitrogen emission lines in the spectrum of the parent lightning. The ball lightning traveled horizontally across the video frame at an average speed equivalent of 8.6 m/s.

Oscillations in the light intensity and in the oxygen and nitrogen emission at a frequency of 100 Hz, possibly caused by the electric field of the 50 Hz high-voltage power transmission line in the vicinity, were observed. From the spectrum, the temperature of the ball lightning was assessed as being lower than the temperature of the parent lightning (<15,000–30,000 K). The observed data are consistent with vaporization of soil as well as with ball lightning's sensitivity to electric fields.[5][41]

Laboratory experiments

Scientists have long attempted to produce ball lightning in laboratory experiments. While some experiments have produced effects that are visually similar to reports of natural ball lightning, it has not yet been determined whether there is any relation.

Nikola Tesla reportedly could artificially produce 1.5" (3.8 cm) balls and conducted some demonstrations of his ability,[42] but he was truly interested in higher voltages and powers, and remote transmission of power, so the balls he made were just a curiosity.[43]

The International Committee on Ball Lightning (ICBL) holds regular symposia on the subject. A related group uses the generic name "Unconventional Plasmas".[44] The next ICBL symposium was tentatively scheduled for July 2012 in San Marcos, Texas but was cancelled due to a lack of submitted abstracts.[45]

Wave-guided microwaves

Ohtsuki and Ofuruton[46][47] described producing “plasma fireballs” by microwave interference within an air-filled cylindrical cavity fed by a rectangular waveguide using a 2.45-GHz, 5-kW (maximum power) microwave oscillator.

Water discharge experiments

Some scientific groups, including the Max Planck Institute, have reportedly produced a ball lightning-type effect by discharging a high-voltage capacitor in a tank of water.[48][49]

Home microwave oven experiments

Many modern experiments involve using a microwave oven to produce small rising glowing balls, often referred to as plasma balls. Generally, the experiments are conducted by placing a lit or recently extinguished match or other small object in a microwave oven. The burnt portion of the object flares up into a large ball of fire, while "plasma balls" float near the oven chamber ceiling. Some experiments describe covering the match with an inverted glass jar, which contains both the flame and the balls so that they don't damage the chamber walls.[50] (a glass jar, however, eventually explodes rather than simply cause charred paint or melting metal, as happens to the inside of a microwave.) Experiments by Eli Jerby and Vladimir Dikhtyar in Israel revealed that microwave plasma balls are made up of nanoparticles with an average radius of 25 nm. The Israeli team demonstrated the phenomenon with copper, salts, water and carbon.[51]

Silicon experiments

Experiments in 2007 involved shocking silicon wafers with electricity, which vaporizes the silicon and induces oxidation in the vapors. The visual effect can be described as small glowing, sparkling orbs that roll around a surface. Two Brazilian scientists, Antonio Pavão and Gerson Paiva of the Federal University of Pernambuco[52] have reportedly consistently made small long-lasting balls using this method.[53][54] These experiments stemmed from the theory that ball lightning is actually oxidized silicon vapors (see vaporized silicon hypothesis, below).

Possible scientific explanations

There is at present no widely accepted explanation for ball lightning. Several theories have been advanced since it was brought into the scientific realm by the English physician and electrical researcher William Snow Harris in 1843,[55] and French Academy scientist François Arago in 1855.[56]

Electrically charged solid-core model

In this model ball lightning is assumed to have a solid, positively charged core. According to this underlying assumption, the core is surrounded by a thin electron layer with a charge nearly equal in magnitude to that of the core. A vacuum exists between the core and the electron layer containing an intense electromagnetic (EM) field, which is reflected and guided by the electron layer. The microwave EM field applies a ponderomotive force (radiation pressure) to the electrons preventing them from falling into the core.[57][58]

Microwave cavity hypothesis

Pyotr Kapitsa proposed that ball lightning is a glow discharge driven by microwave radiation that is guided to the ball along lines of ionized air from lightning clouds where it is produced. The ball serves as a resonant microwave cavity, automatically adjusting its radius to the wavelength of the microwave radiation so that resonance is maintained.[59][60]

The Handel Maser-Soliton theory of ball lightning hypothesizes that the energy source generating the ball lightning is a large (several cubic kilometers) atmospheric maser. The ball lightning appears as a plasma caviton at the antinodal plane of the microwave radiation from the maser.[61]

Soliton hypothesis

Julio Rubenstein, David Finkelstein, and James R. Powell proposed that ball lightning is a detached St. Elmo's fire (1964–1970). St. Elmo's fire arises when a sharp conductor, such as a ship's mast, amplifies the atmospheric electric field to breakdown. For a globe the amplification factor is 3. A free ball of ionized air can amplify the ambient field this much by its own conductivity. When this maintains the ionization, the ball is then a soliton in the flow of atmospheric electricity.

Powell's kinetic theory calculation found that the ball size is set by the second Townsend coefficient (the mean free path of conduction electrons) near breakdown. Wandering glow discharges are found to occur within certain industrial microwave ovens and continue to glow for several seconds after power is shut off. Arcs drawn from high-power low-voltage microwave generators also are found to exhibit after-glow. Powell measured their spectra, and found that the after-glow comes mostly from metastable NO ions, which are long-lived at low temperatures. It occurred in air and in nitrous oxide, which possess such metastable ions, and not in atmospheres of argon, carbon dioxide, or helium, which do not.

Vaporized silicon hypothesis

This hypothesis suggests that ball lightning consists of vaporized silicon burning through oxidation. Lightning striking Earth's soil could vaporize the silica contained within it, and somehow separate the oxygen from the silicon dioxide, turning it into pure silicon vapor. As it cools, the silicon could condense into a floating aerosol, bound by its charge, glowing due to the heat of silicon recombining with oxygen. An experimental investigation of this effect, published in 2007, reported producing "luminous balls with lifetime in the order of seconds" by evaporating pure silicon with an electric arc.[62][63][64] Videos and spectographs of this experiment have been made available.[65][66] This hypothesis got significant supportive data in 2014, when the first ever recorded spectra of natural ball lightning were published.[5][41] The theorized forms of silicon storage in soil include nanoparticles of Si, SiO, and SiC.[67]

Hydrodynamic vortex ring antisymmetry

Physicist Domokos Tar suggested the following theory for ball lightning formation based on his ball lightning observation.[31][68] Lightning strikes perpendicular to the ground, and thunder follows immediately at supersonic speed in the form of shock waves[69] that form an invisible aerodynamic turbulence ring horizontal to the ground. Around the ring, over and under pressure systems rotate the vortex around a circular axis in the cross section of the torus. At the same time, the ring expands concentrically parallel to the ground at low speed.

In an open space, the vortex fades and finally disappears. If the vortex's expansion is obstructed, and symmetry is broken, the vortex breaks into cyclical form. Still invisible, and due to the central and surface tension-forces, it shrinks to an intermediate state of a cylinder, and finally into a ball. The resulting transformation subsequently becomes visible once the energy is concentrated into the final spherical stage.

The ball lightning has the same rotational axis as the rotating cylinder. As the vortex has a much smaller vector of energy compared to the overall energy of the reactant sonic shock wave, its vector is likely fractional to the overall reaction. The vortex, during contraction, gives the majority of its energy to form the ball lightning, achieving nominal energy loss.

In some observations, the ball lightning appeared to have an extremely high energy concentration[68] but this phenomenon hasn't been adequately verified. The present theory concerns only the low energy lightning ball form, with centripetal forces and surface tension. The visibility of the ball lightning can be associated with electroluminescence, a direct result of the triboelectric effect from materials within the area of the reaction. Static discharge from the cylindrical stage imply the existence of contact electrification within the object. The direction of the discharges indicate the cylinder's rotation, and resulting rotational axis of the ball lightning in accordance to the law of laminar flow. If the ball came from the channel, it would have rotate in the opposite direction.

One theory that may account for the wide spectrum of observational evidence is the idea of combustion inside the low-velocity region of spherical vortex breakdown of a natural vortex[vague] (e.g., the 'Hill's spherical vortex').[70]

Nanobattery hypothesis

Oleg Meshcheryakov suggests that ball lightning is made of composite nano or submicrometre particles—each particle constituting a battery. A surface discharge shorts these batteries, causing a current that forms the ball. His model is described as an aerosol model that explains all the observable properties and processes of ball lightning.[71][72][73][74]

Black hole hypothesis

Another hypothesis is that some ball lightning is the passage of microscopic primordial black holes through the Earth's atmosphere. This possibility was mentioned parenthetically by Leo Vuyk in 1992 in a patent application and a second patent application in 1996 by Leendert Vuyk. The first detailed scientific analysis was published by Mario Rabinowitz in Astrophysics and Space Science journal in 1999.[75] It was inspired by M. Fitzgerald’s account of ball lightning on 6 August 1868, in Ireland that lasted 20 minutes and left a 6-metre square hole, a 90-metre long trench, a second trench 25 meters long, and a small cave in the peat bog. Pace VanDevender, a plasma physicist at Sandia National Laboratories in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and his team found depressions consistent with Fitzgerald’s report and inferred that the evidence is inconsistent with thermal (chemical or nuclear) and electrostatic effects. An electromagnetically levitated, compact mass of over 20,000 kg would produce the reported effects but requires a density of more than 2000 times the density of gold, which implies a miniature black hole. He and his team found a second event in the peat-bog witness plate from 1982 and are trying to geolocate electromagnetic emission consistent with the hypothesis. His colleagues at the institute agreed that, implausible though the hypothesis seemed, it was worthy of their attention.[76]

Buoyant plasma hypothesis

The declassified Project Condign report concludes that buoyant charged plasma formations similar to ball lightning are formed by novel physical, electrical, and magnetic phenomena, and that these charged plasmas are capable of being transported at enormous speeds under the influence and balance of electrical charges in the atmosphere. These plasmas appear to originate due to more than one set of weather and electrically charged conditions, the scientific rationale for which is incomplete or not fully understood. One suggestion is that meteors breaking up in the atmosphere and forming charged plasmas as opposed to burning completely or impacting as meteorites could explain some instances of the phenomena, in addition to other unknown atmospheric events.[77]

Transcranial magnetic stimulation

Cooray and Cooray (2008)[78] stated that the features of hallucinations experienced by patients having epileptic seizures in the occipital lobe are similar to the observed features of ball lightning. The study also showed that the rapidly changing magnetic field of a close lightning flash is strong enough to excite the neurons in the brain. This strengthens the possibility of lightning-induced seizure in the occipital lobe of a person close to a lightning strike, establishing the connection between epileptic hallucination mimicking ball lightning and thunderstorms.

More recent research with transcranial magnetic stimulation has been shown to give the same hallucination results in the laboratory (termed magnetophosphenes), and these conditions have been shown to occur in nature near lightning strikes.[79][80] This hypothesis fails to explain observed physical damage caused by ball lightning or simultaneous observation by multiple witnesses. (At the very least, observations would differ substantially.)[citation needed]

Theoretical calculations from University of Innsbruck researchers suggest that the magnetic fields involved in certain types of lightning strikes could potentially induce visual hallucinations resembling ball lightning.[81] Such fields, which are found within close distances to a point in which multiple lightning strikes have occurred over a few seconds, can directly cause the neurons in the visual cortex to fire, resulting in magnetophosphenes (magnetically induced visual hallucinations).[82]

Spinning plasma toroid (ring)

Seward proposes that ball lightning is a spinning plasma toroid or ring. He built a lab that produces lightning level arcs, and by modifying the conditions he produced bright, small balls that mimic ball lightning and persist in atmosphere after the arc ends. Using a high speed camera he was able to show that the bright balls were spinning plasma toroids.[83]

Chen was able to derive the physics and found that there is a class of plasma toroids that remain stable with or without an external magnetic containment, a new plasma configuration unlike anything reported elsewhere.[84]

Seward published images of the results of his experiments, along with his method. Included is a report by a farmer of observing a ball lightning event forming in a kitchen and the effects it caused as it moved around the kitchen. This is the only eye witness account of ball lightning forming, then staying in one area, then ending that the author has heard of.[85]

Rydberg matter concept

Manykin et al. have suggested atmospheric Rydberg matter as an explanation of ball lightning phenomena.[86] Rydberg matter is a condensed form of highly excited atoms in many aspects similar to electron-hole droplets in semiconductors.[87][88] However, in contrast to electron-hole droplets, Rydberg matter has an extended life-time—as long as hours. This condensed excited state of matter is supported by experiments, mainly of a group led by Holmlid.[89] It is similar to a liquid or solid state of matter with extremely low (gas-like) density. Lumps of atmospheric Rydberg matter can result from condensation of highly excited atoms that form by atmospheric electrical phenomena, mainly due to linear lightning. Stimulated decay of Rydberg matter clouds can, however, take the form of an avalanche, and so appear as an explosion.

Other hypotheses

Several other hypotheses have been proposed to explain ball lightning:

- Spinning electric dipole hypothesis. A 1976 article by V. G. Endean postulated that ball lightning could be described as an electric field vector spinning in the microwave frequency region.[90]

- Electrostatic Leyden jar models. Stanley Singer discussed (1971) this type of hypothesis and suggested that the electrical recombination time would be too short for the ball lightning lifetimes often reported.[91]

- J. Pace VanDevender separates extreme ball lightning of the highly energetic violent kind, and proposes a theory of neutrinos and heavy neutrinos.[92]

- Smirnov proposed (1987) a fractal aerogel hypothesis.[93]

- V.P. Torchigin proposed (2003) considering ball lightning as a form of self-confined intense light.[94]

- M.I. Zelikin proposed (2006) an explanation (with a rigorous mathematical foundation) based on the hypothesis of plasma superconductivity.[95]

- Ph. M. Papaelias studied (1984) the antimatter meteor hypothesis as a possible explanation of ball lightning formation. He compared all properties of ball lightning to those expected by an antimatter meteor undergoing annihilation by atmospheric molecules and found almost identical properties.[96]

See also

Notes

- ^ a b J. B[rooking] R[owe], ed. (1905). The Two Widecombe Tracts, 1638[,] giving a Contemporary Account of the great Storm, reprinted with an Introduction. Exeter: James G Commin. Retrieved 29 June 2013.

- ^ a b Day, Jeremiah (January 1813). "A view of the theories which have been proposed to explain the origin of meteoric stones". The General Repository and Review. 3 (1). Cambridge, Massachusetts: William Hilliard: 156–157. Retrieved 29 June 2013.

- ^ How Stuff Works entry. Retrieved 21 Jan 2014.

- ^ Anna Salleh (20 March 2008). "Ball lightning bamboozles physicist". 35.2772;149.1292: Abc.net.au. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ a b c d Cen, Jianyong; Yuan, Ping; Xue, Simin (17 January 2014). "Observation of the Optical and Spectral Characteristics of Ball Lightning". Physical Review Letters. 112 (035001). American Physical Society. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- ^ Slezak, Michael (16 January 2014). "Natural ball lightning probed for the first time". New Scientist. Retrieved 22 January 2014.

- ^ a b Anon. "Ask the experts". Scientific American. Retrieved 4 April 2007.

- ^ McNally, J. R. (1960). "Preliminary Report on Ball Lightning". Proceedings of the Second Annual Meeting of the Division of Plasma Physics of the American Physical Society (Paper J-15 ed.). Gatlinburg. pp. 1–25.

{{cite conference}}: Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Grigoriev, A. I. (1988). Y. H. Ohtsuki (ed.). "Statistical Analysis of the Ball Lightning Properties". Science of Ball Lightning. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Co.: 88–134.

- ^ Harrison, Prof. G. B. (21 April 1976). "Letters to the editor: Ball lightning". The Times. Times Newspapers Limited.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Anon. "Foreign Affairs: Bristol 17 December". Weekly Journal or British Gazetteer. 24 December 1726.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Anon (24 December 1726). "Foreign Affairs: London 24 December". London Journal.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Clarke, Ronald W. (1983). Benjamin Franklin, A Biography. Random House. p. 87. ISBN 978-1-84212-272-3. Archived from the original on 12 January 2012.

- ^ Simons, Paul (17 February 2009). "Weather Eye Charles Darwin the meteorologist". The Times. London. Retrieved 16 April 2010.

- ^ http://www.thenational.ae/article/20090223/FRONTIERS/646186738/1036

- ^ Brewer, Ebenezer Cobham (1864). A Guide to the Scientific Knowledge of Things Familiar. pp. 13–14. Retrieved 22 January 2014.

- ^ de Fonvielle, Wilfrid (1875). "Chapter X Globular lightning". Thunder and lightning (full text). translated by T L Phipson. pp. 32–39. ISBN 978-1-142-61255-9. Retrieved 22 January 2014.

- ^ Anon (24 December 1867). "Globular lightning". The Leeds mercury. Leeds, UK.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ "Tsar-Martyr Nicholas II And His Family". Orthodox.net. Archived from the original on 17 June 2009. Retrieved 13 July 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ There is no present-day Lake Pasquaney in New Hampshire, United States. New Hampshire's Newfound Lake has a Camp Pasquaney. However, part of the lake is known as Pasquaney Bay.

- ^ Crowley, Aleister (5 December 1989). "Chp. 83". The Confessions of Aleister Crowley: An Autobiography. Penguin. ISBN 0-14-019189-5.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Jennison, R. C. (1969). Nature. 224: 895. Bibcode:1969Natur.224..895J. doi:10.1038/224895a0.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|trans_title=,|laydate=,|laysummary=,|laysource=, and|separator=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Miracle saved panth". Sikhnet.com. 21 December 2009. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

- ^ Golden Globe, 24 November 1894.

- ^ "The Cape Naturaliste Lighthouse". Lighthouses of Western Australia. Lighthouses of Australia Inc. Retrieved 13 July 2009.

- ^ Wilder, Laura Ingalls (1937). On the Banks of Plum Creek. Harper Trophy. ISBN 0-06-440005-0.

- ^ Getline, Meryl (17 October 2005). "Playing with (St. Elmo's) fire". USA Today.

- ^ "Ball lightning – and the charge sheath vortex". Peter-thomson.co.uk. Retrieved 13 July 2009.

- ^ This may be an incorrect translation of the word "blixtlokaliseringssystem" from the university article cited in the sources

- ^ Larsson, Anders (23 April 2002). "Ett fenomen som gäckar vetenskapen" (in Swedish). Uppsala University. Retrieved 19 November 2007.

- ^ a b "Fizikai Szemle 2004/10". Kfki.hu. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

- ^ Domokos Tar (2009). "Observation of Lightning Ball (Ball Lightning): A new phenomenological description of the phenomenon". Proceedings of the 9-th International Symposium on Ball Lightning, Aug. Eindhoven. 0910: 783. arXiv:0910.0783. Bibcode:2009arXiv0910.0783T.

- ^ Domokos Tar (2010). "Lightning Ball (Ball Lightning) Created by Thunder, Shock-Wave". arXiv:1007.3348 [physics.gen-ph].

- ^ Domokos Tar (2009). "New Revelation of Lightning Ball Observation and Proposal for a Nuclear Reactor Fusion Experiment". Proceedings 10th International Symposium on Ball Lightning (ISBL-08), July 7–12 Kaliningrad, Russia, pp.135–141, Eds. Vladimir L. Bychkov & Anatoly I. Nikitin. 0910: 2089. arXiv:0910.2089. Bibcode:2009arXiv0910.2089T.

- ^ 11. července 2011 16:54. "Source (in Czech)". Zpravy.idnes.cz. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "BL_Info_10". Ernmphotography.com. Retrieved 13 July 2009.

- ^ "Unusual Phenomea Reports: Ball Lightning". Amasci.com. Retrieved 13 July 2009.

- ^ Barry, James Dale: Ball lightning and bead lightning: extreme forms of atmospheric electricity, ISBN 0-306-40272-6, 1980, Plenum Press (p.35) [1]

- ^ Barry, J.D. (1980a) Ball Lightning and Bead Lightning: Extreme Forms of Atmospheric Electricity. 8–9. New York and London: Plenum Press. ISBN 0-306-40272-6

- ^ Charman, Neil (14 December 1972). "The enigma of ball Lightning". New Scientist. 56 (824). Reed Business information: 632–635. Retrieved 10 May 2010.

- ^ a b c Ball, Philip (17 January 2014). "Focus: First Spectrum of Ball Lightning". Focus. American Physical Society. doi:10.1103/Physics.7.5. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- ^ "The New Wizard of the West". Homepage.ntlworld.com. Retrieved 13 July 2009.

- ^ Tesla, Nikola (1978). Nikola Tesla – Colorado Springs Notes 1899–1900. Nolit (Beograd, Yugoslavia), 368–370. ISBN 978-0-913022-26-9

- ^ Anon (2008). "Tenth international syposium on ball lightning/ International symposium III on unconventional plasmas". ICBL. Retrieved 10 May 2010.

- ^ Template:Wayback

- ^ Ohtsuki, Y. H. (1991). "Plasma fireballs formed by microwave interference in air". Nature. 350 (6314): 139. Bibcode:1991Natur.350..139O. doi:10.1038/350139a0.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|separator=,|trans_title=,|laysummary=,|laydate=, and|laysource=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Ohtsuki, Y. H. (1991). "Plasma fireballs formed by microwave interference in air (Corrections)". Nature. 353 (6347): 868. Bibcode:1991Natur.353..868O. doi:10.1038/353868a0.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|separator=,|trans_title=,|laysummary=,|laydate=, and|laysource=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "'Ball lightning' created in German laboratory | COSMOS magazine". COSMOS magazine. 7 June 2006. Retrieved 13 July 2009.

- ^ Youichi Sakawa (12 July 2006). "Fireball Generation in a Water Discharge". Plasma and Fusion Research: Rapid Communications. Retrieved 13 July 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)[dead link] - ^ "How to make a Stable Plasmoid ( Ball Lightning ) with the GMR (Graphite Microwave Resonator) by Jean-Louis Naudin". Jlnlabs.online.fr. 22 December 2005. Archived from the original on 26 June 2009. Retrieved 13 July 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Creating the 4th state of matter with microwaves by Halina Stanley". scienceinschool.org. 13 August 2009. Archived from the original on 31 October 2009. Retrieved 6 October 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Universidade Federal de Pernambuco". Ufpe.br. Archived from the original on 21 June 2009. Retrieved 13 July 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Pesquisadores da UFPE geram, em laboratório, fenômeno atmosférico conhecido como bolas luminosas". Ufpe.br. 16 January 2007. Archived from the original on 20 December 2008. Retrieved 13 July 2009.

- ^ "Ball Lightning Mystery Solved? Electrical Phenomenon Created in Lab". News.nationalgeographic.com. 21 November 2005. Retrieved 13 July 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Snow Harris, William (2008 (originally published in 1843)). "Section I". On the nature of thunderstorms (Reprint ed.). Bastian Books. pp. 34–43. ISBN 0-554-87861-5. Retrieved 11 May 2010.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ François Arago, Meteorological Essays by , Longman, 1855

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1029/GL017i012p02277, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1029/GL017i012p02277instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.5194/angeo-28-223-2010, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.5194/angeo-28-223-2010instead. - ^ Капица, П. Л. (1955). "О природе шаровой молнии". Докл. Акад. наук СССР (in Russian). 101: 245.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Kapitsa, Peter L. (1955). "The Nature of Ball Lightning". In Donald J. Ritchie (ed.). Ball Lightning: A Collection of Soviet Research in English Translation (1961 ed.). Consultants Bureau, New York. pp. 11–16. Retrieved 22 January 2014.

- ^ Handel, Peter H. (1994). "Development of the maser-caviton ball lightning theory". J. Geophys. Res. 99: 10689. Bibcode:1994JGR....9910689H. doi:10.1029/93JD01021.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Paiva, Gerson Silva (2007). "Production of Ball-Lightning-Like Luminous Balls by Electrical Discharges in Silicon". Phys. Rev. Lett. 98 (4): 048501. Bibcode:2007PhRvL..98d8501P. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.98.048501. PMID 17358820.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Lightning balls created in the lab". New Scientist. 10 January 2007.

A more down-to-earth theory, proposed by John Abrahamson and James Dinniss at the University of Canterbury in Christchurch, New Zealand, is that ball lightning forms when lightning strikes soil, turning any silica in the soil into pure silicon vapour. As the vapour cools, the silicon condenses into a floating aerosol bound into a ball by charges that gather on its surface, and it glows with the heat of silicon recombining with oxygen.

- ^ "Ball Lightning Mystery Solved? Electrical Phenomenon Created in Lab". National Geographic News. 22 January 2007.

- ^ ftp://ftp.aip.org/epaps/phys_rev_lett/E-PRLTAO-98-047705/

- ^ Slezak, Michael. "Natural ball lightning probed for the first time". New Scientist. Retrieved 17 January 2014.

- ^ Abrahamson, John (2000). "Ball lightning caused by oxidation of nanoparticle networks from normal lightning strikes on soil". Nature. 403 (6769): 519–21. doi:10.1038/35000525.

- ^ a b "[0910.0783v1] Observation of Lightning Ball (Ball Lightning): A new phenomenological description of the phenomenon". Arxiv.org. 5 October 2009. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

- ^ "[1007.3348] Lightning Ball (Ball Lightning) Created by Thunder, Shock-Wave". Arxiv.org. 20 July 2010. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

- ^ Coleman, PF (1993). "An explanation for ball lightning?". Weather. 48: 30.

- ^ Meshcheryakov, Oleg (2007). "Ball Lightning–Aerosol Electrochemical Power Source or A Cloud of Batteries" (PDF). Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2 (3): 319. Bibcode:2007NRL.....2..319M. doi:10.1007/s11671-007-9068-2. Retrieved 27 June 2007.

- ^ "Ball lightning's frightening . . . but finally explained". EE Times. 29 August 2007.

- ^ Meshcheryakov, Oleg (1 August 2010). "How and why electrostatic charge of combustible nanoparticles can radically change the mechanism and rate of their oxidation in humid atmosphere". arXiv:1008.0162 [physics.plasm-ph].

- ^ Meshcheryakov, Oleg (2013). "Why not only electrostatic discharge but even a minimum charge on the surface of highly sensitive explosives can catalyze their gradual exothermic decomposition and how a cloud of unipolar charged explosive particles turns into ball lightning". Proceedings of the Nanotech 2013 Conference. Washington. pp. 619–622.

{{cite conference}}: Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Mario Rabinowitz (11 December 2002). "[astro-ph/0212251] Little Black Holes:Dark Matter And Ball Lightning". Astrophys.Space Sci. 262 (4). Arxiv.org: 391–410. arXiv:astro-ph/0212251. Bibcode:1998Ap&SS.262..391R. doi:10.1023/A:1001865715833.

- ^ Muir, Hazel (23 December 2006). "Blackholes in your backyard". New Scientist. 192 (2583/2584): 48–51. doi:10.1016/S0262-4079(06)61459-0.

- ^ http://www.disclosureproject.org/docs/pdf/uap_exec_summary_dec00.pdf | UAP in the UK Air Defence Region, Executive Summary, Page 7, Defence Intelligence Staff, 2000

- ^ Could some ball lightning observations be optical hallucinations caused by epileptic seizures, Cooray, G. and V. Cooray, The open access atmospheric science journal, vol. 2, pp. 101–105 (2008)

- ^ Peer; Kendl (2010). "Transcranial stimulability of phosphenes by long lightning electromagnetic pulses". Physics Letters A. 374 (29): 2932–2935. arXiv:1005.1153. Bibcode:2010PhLA..374.2932P. doi:10.1016/j.physleta.2010.05.023.

- Erratum: Physics Letters A. 347 (47): 4797–4799.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)

- Erratum: Physics Letters A. 347 (47): 4797–4799.

- ^ Ball lightning is all in the mind, say Austrian physicists, The Register, 19 May 2010

- ^ Peer; Kendl (2010). "Transcranial stimulability of phosphenes by long lightning electromagnetic pulses". Physics Letters A. 374 (29): 2932–2935. arXiv:1005.1153. Bibcode:2010PhLA..374.2932P. doi:10.1016/j.physleta.2010.05.023.

- Erratum: Physics Letters A. 347 (47): 4979–4799. 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)

- Erratum: Physics Letters A. 347 (47): 4979–4799. 2010.

- ^ Emerging Technology From the arXiv May 11, 2010 (11 May 2010). "Magnetically Induced Hallucinations Explain Ball Lightning, Say Physicists – Technology Review". Technologyreview.com. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Seward, C., Chen, C., Ware, K. “Ball Lightning Explained as a Stable Plasma Toroid.” PPPS- 2001 Pulsed Power Plasma Science Conference. June 2001.

- ^ Chen, C., Pakter, R., Seward, D. C. “Equilibrium and Stability Properties of Self-Organized Electron Spiral Toroids.” Physics of Plasmas. Vol. 8, No. 10, pp. 4441–4449. October 2001.

- ^ Seward, Clint. “Ball Lightning Explanation Leading to Clean Energy.” Amazon.com. 2011.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1117/12.675004, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1117/12.675004instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1134/1.1355396, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1134/1.1355396instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1134/S0021364010210125, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1134/S0021364010210125instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1088/0953-8984/19/27/276206, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1088/0953-8984/19/27/276206instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1038/263753a0, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1038/263753a0instead. - ^ Singer, Stanley (1971). The Nature of Ball Lightning. New York: Plenum Press.

- ^ "The IEEE, Plasma Cosmology and Extreme Ball Lightning". Thunderbolts.info. Retrieved 13 July 2009.

- ^ Smirnov 1987, Physics Reports, (Review Section of Physical Letters), 152, No. 4, pp. 177–226.

- ^ Torchigin, V.P. (2009). "Ball Lightning as an Optical Incoherent Space Spherical Soliton in Handbook of Solitons: Research, Technology and Applications editors S.P. Lang and S.H. Bedore". New York: Novapublishers: 3–54.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1007/s10958-008-9047-x, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1007/s10958-008-9047-xinstead. - ^ Papaelias, Ph. M.,(1984). PhD Thesis , Athens Greece and Proceedings of ISBL 06 Conference of Ball Lightning 2006.

Further reading

- Barry, James Dale (1980). Ball Lightning and Bead Lightning. New York: Plenum Press. ISBN 0-306-40272-6.

- Cade, Cecil Maxwell (1969). The Taming of the Thunderbolts. New York: Abelard-Schuman Limited. ISBN 0-200-71531-3.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Coleman, Peter F. (2004). Great Balls of Fire—A Unified Theory of Ball Lightning, UFOs, Tunguska and other Anomalous Lights. Christchurch, NZ: Fireshine Press. ISBN 1-4116-1276-0.

- Coleman, P.F. 2006, J.Sci.Expl., Vol. 20, No.2, 215–238.

- Golde, R. H. (1977). Lightning. Bristol: John Wright and Sons Limited. ISBN 0-12-287802-7.

- Golde, R. H. (1977). Lightning Volume 1 Physics of Lightning. Academic Press.

- Seward, Clint (2011), Ball Lightning Explanation Leading to Clean Energy, ISBN 978-1-4583-7373-1 Amazon.com

- Stenhoff, Mark (1999). Ball Lightning – An Unsolved Problem in Atmospheric Physics. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. ISBN 0-306-46150-1.

- Uman, Martin A. (1984). Lightning. Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-25237-X.

- Viemeister, Peter E. (1972). The Lightning Book. Cambridge: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-22017-2.