Frank Sturgis: Difference between revisions

Magioladitis (talk | contribs) m clean up using AWB (10003) |

Greenboite (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

Sturgis met up with Castro and his 400 rebels in the [[Sierra Maestra]] mountains. Sturgis offered to train Castro’s troops in guerrilla warfare. Castro accepted the offer, but he also had an immediate need for guns and ammunition, so Sturgis became a gunrunner. Using money from anti-Batista Cuban exiles in Miami, Sturgis purchased boatloads of weapons and ammunition from [[CIA]] weapons expert [[Samuel Cummings]]' [[International Armament Corporation]] in [[Alexandria, Virginia]]. Sturgis explained later that he chose to throw in with Castro rather than Prio because Fidel was a soldier, a man of action, whereas Prio was a politician, more a man of words.<ref>Jim Hunt and Bob Risch, ''Warrior'' (New York: A Forge Book, May 2011), p. 39.</ref> In March 1958, Sturgis opened a training camp in the Sierra Maestra mountains, where he taught [[Che Guevara]] and other [[26th of July Movement]] rebel soldiers guerrilla warfare.<ref>Jim Hunt and Bob Risch, ''Warrior'' (New York: A Forge Book, May 2011), p. 43.</ref> When the revolution ended in January 1959, Castro appointed Sturgis gambling czar and director of security and intelligence for the air force, in addition to his position as a captain in the 26th of July Brigade.<ref>Jim Hunt and Bob Risch, ''Warrior'' (New York: A Forge Book, May 2011), p. 57.</ref> |

Sturgis met up with Castro and his 400 rebels in the [[Sierra Maestra]] mountains. Sturgis offered to train Castro’s troops in guerrilla warfare. Castro accepted the offer, but he also had an immediate need for guns and ammunition, so Sturgis became a gunrunner. Using money from anti-Batista Cuban exiles in Miami, Sturgis purchased boatloads of weapons and ammunition from [[CIA]] weapons expert [[Samuel Cummings]]' [[International Armament Corporation]] in [[Alexandria, Virginia]]. Sturgis explained later that he chose to throw in with Castro rather than Prio because Fidel was a soldier, a man of action, whereas Prio was a politician, more a man of words.<ref>Jim Hunt and Bob Risch, ''Warrior'' (New York: A Forge Book, May 2011), p. 39.</ref> In March 1958, Sturgis opened a training camp in the Sierra Maestra mountains, where he taught [[Che Guevara]] and other [[26th of July Movement]] rebel soldiers guerrilla warfare.<ref>Jim Hunt and Bob Risch, ''Warrior'' (New York: A Forge Book, May 2011), p. 43.</ref> When the revolution ended in January 1959, Castro appointed Sturgis gambling czar and director of security and intelligence for the air force, in addition to his position as a captain in the 26th of July Brigade.<ref>Jim Hunt and Bob Risch, ''Warrior'' (New York: A Forge Book, May 2011), p. 57.</ref> |

||

It is believed{{By whom|date=January 2013}} that during this time Sturgis worked as a [[Mercenary|soldier of fortune]] or a contract agent for the [[Central Intelligence Agency]].{{citation needed|date=June 2013}} The 1975 [[United States President's Commission on CIA activities within the United States|Rockefeller Commission]] report, however, found that "Frank Sturgis was not an employee or agent of the [[CIA]] either in 1963 or at any other time."<ref>[http://mcadams.posc.mu.edu/hunt_sturgis.htm Report to the President by the Commission on CIA Activities Within the United States] Chapter 19</ref> |

It is believed{{By whom|date=January 2013}} that during this time Sturgis worked as a [[Mercenary|soldier of fortune]] or a contract agent for the [[Central Intelligence Agency]].{{citation needed|date=June 2013}} The 1975 [[United States President's Commission on CIA activities within the United States|Rockefeller Commission]] report, however, found that "Frank Sturgis was not an employee or agent of the [[CIA]] either in 1963 or at any other time."<ref>[http://mcadams.posc.mu.edu/hunt_sturgis.htm Report to the President by the Commission on CIA Activities Within the United States] Chapter 19</ref> Rather it appears that Sturgis was a contract hire of the CIA. |

||

==Watergate burglary 1972== |

==Watergate burglary 1972== |

||

Revision as of 06:20, 25 March 2014

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2009) |

Frank Anthony Sturgis | |

|---|---|

| Born | Frank Angelo Fiorini 9 December 1924 |

| Died | 4 December 1993 |

| Occupation(s) | military, spies |

| Watergate scandal |

|---|

|

| Events |

| People |

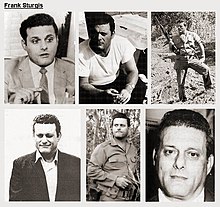

Frank Anthony Sturgis (December 9, 1924 – December 4, 1993), born Frank Angelo Fiorini, was one of the five Watergate burglars.[1] He served in several branches of the United States military, aided Fidel Castro in the Cuban revolution of 1958, and worked as an undercover operative.

Early life and military service

When still a child, his family moved to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. On October 5, 1942, in his senior year of high school, 17-year-old Frank Angelo Fiorini joined the United States Marine Corps and served under Col. "Red Mike" Merritt A. Edson in the First Marine Raider Battalion in the Pacific Theater during the Second World War.[2] Honorably discharged as a corporal in 1945, he joined the Norfolk police force on June 5, 1946. He soon discovered a corrupt payoff system and brought it to the attention of his superiors, who told him to overlook the illegal activities. On October 5, 1946 he had a confrontation with his sergeant and resigned the same day. For the next 18 months, he managed the Havana-Madrid tavern in Norfolk that catered to foreigners, mostly Cuban merchant seamen.

On November 9, 1947, Fiorini joined the United States Naval Reserve at the Norfolk Naval Air Station and learned to fly while still working at the tavern. He was honorably discharged on August 30, 1948 and joined the United States Army the next day. He was sent immediately to West Berlin, where the USSR had closed the land routes during the Berlin Blockade, and he became a member of General Lucius Clay's honor guard. Two weeks after the USSR reopened the land routes on May 11, 1949, Fiorini was honorably discharged. As a Marine Raider, Fiorini had worked behind enemy lines gathering intelligence, and during his Army tenure in Berlin and Heidelberg, he had a top secret clearance and worked in an intelligence unit whose primary target was the Soviet Union. Fiorini started to believe Russia was a threat, and he became a lifelong militant. Returning to Norfolk in 1952, he took a job managing the Cafe Society tavern, then partnered with its owner, Milton Bass, to co-purchase and manage The Top Hat Nightclub in Virginia Beach.[3]

Fiorini attended the Virginia Polytechnic Institute before becoming the manager of the Whitehorse Tavern in Norfolk, Virginia.[4] While in Norfolk, Virginia he attended a few classes at Old Dominion University before joining the Norfolk Police Department.[citation needed]

Intelligence activities 1952-1962

On September 23, 1952, Frank Fiorini filed a petition in the Circuit Court of the City of Norfolk, Virginia, to change his name to Frank Anthony Sturgis, adopting the surname of his stepfather Ralph Sturgis, whom his mother had married in 1937. His new name resembled that of Hank Sturgis, the fictional hero of E. Howard Hunt's 1949 novel, Bimini Run, whose life parallels Frank Sturgis' life from 1942 to 1949 in certain salient respects.[5]

Moves to Cuba, joins Castro forces

Sturgis moved to Miami in 1957, where the Cuban wife of his uncle Angelo Vona introduced him to former Cuban president Carlos Prio, who joined with other Cubans opposing dictator Fulgencio Batista to plot their return to power. They were sending money to Mexico to support Fidel Castro. Prio asked Sturgis to go to Cuba to join up with Castro and to report back to the exiled powers in Miami.[6]

Sturgis met up with Castro and his 400 rebels in the Sierra Maestra mountains. Sturgis offered to train Castro’s troops in guerrilla warfare. Castro accepted the offer, but he also had an immediate need for guns and ammunition, so Sturgis became a gunrunner. Using money from anti-Batista Cuban exiles in Miami, Sturgis purchased boatloads of weapons and ammunition from CIA weapons expert Samuel Cummings' International Armament Corporation in Alexandria, Virginia. Sturgis explained later that he chose to throw in with Castro rather than Prio because Fidel was a soldier, a man of action, whereas Prio was a politician, more a man of words.[7] In March 1958, Sturgis opened a training camp in the Sierra Maestra mountains, where he taught Che Guevara and other 26th of July Movement rebel soldiers guerrilla warfare.[8] When the revolution ended in January 1959, Castro appointed Sturgis gambling czar and director of security and intelligence for the air force, in addition to his position as a captain in the 26th of July Brigade.[9]

It is believed[by whom?] that during this time Sturgis worked as a soldier of fortune or a contract agent for the Central Intelligence Agency.[citation needed] The 1975 Rockefeller Commission report, however, found that "Frank Sturgis was not an employee or agent of the CIA either in 1963 or at any other time."[10] Rather it appears that Sturgis was a contract hire of the CIA.

Watergate burglary 1972

On June 17, 1972, Sturgis, Virgilio González, Eugenio Martínez, Bernard Barker and James W. McCord, Jr. were arrested while installing electronic listening devices in the national Democratic Party campaign offices located at the Watergate office complex in Washington. The phone number of Hunt was found in address books of the burglars. Reporters were able to link the break-in to the White House. The burglars had made an earlier successful entry to the same location several weeks earlier, but returned to fix a malfunctioning device and to photograph more documents. Bob Woodward, a reporter working for the Washington Post was told by a source (Deep Throat) who was employed by the government that senior aides of President Richard Nixon had paid the burglars to obtain information about his political opponents.

Prison and later investigations

In January 1973, Sturgis, Hunt, Gonzalez, Martinez, Barker, G. Gordon Liddy and James W. McCord were convicted of conspiracy, burglary and wiretapping. While in prison, Sturgis gave an interview to Andrew St. George. Sturgis told St. George: "I will never leave this jail alive if what we discussed about Watergate does not remain a secret between us. If you attempt to publish what I've told you, I am a dead man."

St. George's article was published in True magazine in August 1974. Sturgis claims that the Watergate burglars had been instructed to find a particular document in the Democratic Party offices. This was a "secret memorandum from the Castro government" that included details of CIA covert actions. Sturgis said "that the Castro government suspected the CIA did not tell the whole truth about this operations even to American political leaders".

In an interview with New York Daily News reporter Paul Meskil on June 20, 1975, Sturgis stated, “I was a spy. I was involved in assassination plots and conspiracies to overthrow several foreign governments including Cuba, Panama, Guatemala, the Dominican Republic, and Haiti. I smuggled arms and men into Cuba for Castro and against Castro. I broke into intelligence files. I stole and photographed secret documents. That’s what spies do.”

JFK conspiracy allegations

Early allegations: Sturgis as one of the "three tramps"

The Dallas Morning News, the Dallas Times Herald, and the Fort Worth Star-Telegram photographed three transients under police escort near the Texas School Book Depository shortly after the assassination of Kennedy.[11] The men later became known as the "three tramps".[12] According to Vincent Bugliosi, allegations that these men were involved in a conspiracy originated from theorist Richard E. Sprague who compiled the photographs in 1966 and 1967, and subsequently turned them over to Jim Garrison during his investigation of Clay Shaw.[12] Appearing before a nationwide audience on the December 31, 1968 episode of The Tonight Show, Garrison held up a photo of the three and suggested they were involved in the assassination.[12] Later, in 1974, assassination researchers Alan J. Weberman and Michael Canfield compared photographs of the men to people they believed to be suspects involved in a conspiracy and said that two of the men were Watergate burglars Hunt and Sturgis.[13] Comedian and civil rights activist Dick Gregory helped bring national media attention to the allegations against Hunt and Sturgis in 1975 after obtaining the comparison photographs from Weberman and Canfield.[13] Immediately after obtaining the photographs, Gregory held a press conference that received considerable coverage and his charges were reported in Rolling Stone and Newsweek.[13][14][15]

The Rockefeller Commission reported in 1975 that they investigated the allegation that Hunt and Sturgis, on behalf of the CIA, participated in the assassination of Kennedy.[16] The final report of that commission stated that witnesses who testified that the "derelicts" bore a resemblance to Hunt or Sturgis "were not shown to have any qualification in photo identification beyond that possessed by an average layman".[17] Their report also stated that FBI Agent Lyndal L. Shaneyfelt, "a nationally-recognized expert in photoidentification and photoanalysis" with the FBI photographic laboratory, had concluded from photo comparison that none of the men were Hunt or Sturgis.[18] In 1979, the House Select Committee on Assassinations reported that forensic anthropologists had again analyzed and compared the photographs of the "tramps" with those of Hunt and Sturgis, as well as with photographs of Thomas Vallee, Daniel Carswell, and Fred Lee Chrisman.[19] According to the Committee, only Chrisman resembled any of the tramps but determined that he was not to be in Dealey Plaza on the day of the assassination.[19] In 1992, journalist Mary La Fontaine discovered the November 22, 1963 arrest records that the Dallas Police Department had released in 1989, which named the three men as Gus W. Abrams, Harold Doyle, and John F. Gedney.[20] According to the arrest reports, the three men were "taken off a boxcar in the railroad yards right after President Kennedy was shot", detained as "investigative prisoners", described as unemployed and passing through Dallas, then released four days later.[20]

Posthumous allegations: Hunt's "deathbed confession"

After the death of Hunt in 2007, Howard St. John Hunt and David Hunt stated that their father had recorded several claims about himself and others being involved in a conspiracy to assassinate John F. Kennedy.[21][22] In the April 5, 2007 issue of Rolling Stone, Howard St. John Hunt detailed a number of individuals purported to be implicated by his father including Sturgis, as well as Lyndon B. Johnson, Cord Meyer, David Sánchez Morales, David Atlee Phillips, Lucien Sarti, and William Harvey.[22][23] The two sons alleged that their father cut the information from his memoirs, "American Spy: My Secret History in the CIA, Watergate and Beyond", to avoid possibly perjury charges.[21] According to Hunt's widow and other children, the two sons took advantage of Hunt's loss of lucidity by coaching and exploiting him for financial gain.[21] The Los Angeles Times said they examined the materials offered by the sons to support the story and found them to be "inconclusive".[21]

Later life

In 1979, Sturgis traveled to Angola to help rebels fighting the communist government, which was supported by Cuba and the Soviet Union, and to teach guerrilla warfare. In 1981 he went to Honduras to train the US backed Contras who were fighting Nicaragua's Sandinista government, which was supported by Cuba and the Soviet Union; the Army of El Salvador; and the Honduras death squads. He made a second trip to Angola and trained rebels in the Angolan bush for Holden Roberto. He interacted with Venezuelan terrorist Carlos the Jackal. In 1989 he visited Yassir Arafat in Tunis. Arafat shared elements of his peace plan, and Sturgis was debriefed by the CIA on his return.[24]

In an obituary published December 5, 1993, the New York Times quoted Sturgis' lawyer, Ellis Rubin, as saying that Sturgis died of cancer a week after he was admitted to a veterans hospital in Miami, five days shy of his 69th birthday. It was reported that doctors diagnosed lung cancer that had spread to his kidneys, and that he was survived by a wife, Jan, and a daughter.[1] The Marine Corps performed a twenty-one gun salute and "Taps" at his funeral. Since Sturgis was a war veteran, the Veterans Administration was supposed to provide a headstone, but never did, Sturgis was buried in an unmarked grave in a cemetery south of Miami.[25]

Notes

- ^ a b "Frank A. Sturgis, Is Dead at 68; A Burglar in the Watergate Affair". The New York Times. New York. December 5, 1993. Retrieved December 31, 2012.

- ^ Jim Hunt and Bob Risch, Warrior (New York: A Forge Book, May 2011), p. 25-26.

- ^ Jim Hunt and Bob Risch, Warrior (New York: A Forge Book, May 2011), p. 30-44.

- ^ http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/JFKsturgis.htm

- ^ Chapter 19 of the Rockefeller Commission report denied the suggestion that Sturgis took his present name from the Hunt character, or that the name change was associated in any way with Sturgis' knowing Hunt before 1971 or 1972.

- ^ Jim Hunt and Bob Risch, Warrior (New York: A Forge Book, May 2011), p. 38.

- ^ Jim Hunt and Bob Risch, Warrior (New York: A Forge Book, May 2011), p. 39.

- ^ Jim Hunt and Bob Risch, Warrior (New York: A Forge Book, May 2011), p. 43.

- ^ Jim Hunt and Bob Risch, Warrior (New York: A Forge Book, May 2011), p. 57.

- ^ Report to the President by the Commission on CIA Activities Within the United States Chapter 19

- ^ Bugliosi, Vincent (2007). Reclaiming History: The Assassination of President John F. Kennedy. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. p. 930. ISBN 0-393-04525-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ a b c Bugliosi 2007, p. 930.

- ^ a b c Bugliosi 2007, p. 931.

- ^ Weberman, Alan J; Canfield, Michael (1992) [1975]. Coup D'Etat in America: The CIA and the Assassination of John F. Kennedy (Revised ed.). San Francisco: Quick American Archives. p. 7. ISBN 9780932551108.

- ^ Dallas: new questions and answers, Newsweek, 28 April 1975, p.37-8

- ^ "Chapter 19: Allegations Concerning the Assassination of President Kennedy". Report to the President by Commission on CIA Activities in the United States. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office. June 1975. p. 251.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Report to the President by Commission on CIA Activities in the United States, Chapter 19 1975, p. 256.

- ^ Report to the President by Commission on CIA Activities in the United States, Chapter 19 1975, p. 257.

- ^ a b "I.B. Scientific acoustical evidence establishes a high probability that two gunmen fired at President John F. Kennedy. Other scientific evidence does not preclude the possibility of two gunmen firing at the President. Scientific evidence negates some specific conspiracy allegations". Report of the Select Committee on Assassinations of the U.S. House of Representatives. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office. 1979. pp. 91–92.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Bugliosi 2007, p. 933.

- ^ a b c d Williams, Carol J. (March 20, 2007). "Watergate plotter may have a last tale". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles. Retrieved December 30, 2012.

- ^ a b Hedegaard, Erik (April 5, 2007). "The Last Confessions of E. Howard Hunt". Rolling Stone.

- ^ McAdams, John (2011). "Too Much Evidence of Conspiracy". JFK Assassination Logic: How to Think About Claims of Conspiracy. Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books. p. 189. ISBN 9781597974899. Retrieved December 30, 2012.

- ^ Jim Hunt and Bob Risch, Warrior (New York: A Forge Book, May 2011), p. 313-314.

- ^ Jim Hunt and Bob Risch, Warrior (New York: A Forge Book, May 2011), p. 277.

Bibliography

- Escalante, Fabian. 1995. The Secret War: CIA Covert Operations Against Cuba, 1959-62 ISBN 1-875284-86-9

- Schlesinger, Arthur M. 1978. Robert Kennedy and His Times. ISBN 978-0-233-97085-1

- Waldron, Lamar, with Thom Hartmann. 2009. Legacy of Secrecy.

External links

- Sturgis Spartacus Biography

- "Frank Sturgis". Find a Grave. Retrieved March 14, 2010.

- 1924 births

- 1993 deaths

- American military personnel of World War II

- American spies

- Cancer deaths in Florida

- Cold War spies

- Deaths from lung cancer

- Opposition to Fidel Castro

- People associated with the John F. Kennedy assassination

- People from Miami, Florida

- People from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

- People of the Central Intelligence Agency

- United States Army soldiers

- United States Marines

- Watergate break-in team members