Sculpture in the Indian subcontinent: Difference between revisions

TanmayaPanda (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

TanmayaPanda (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

File:NatarajaMET.JPG|Hindu, [[Chola]] period, 1000 |

File:NatarajaMET.JPG|Hindu, [[Chola]] period, 1000 |

||

image:WLA lacma Celestial Nymph ca 1450 Rajasthan.jpg|Marble Sculpture of female [[yakshi]] in typical curving pose, c. 1450, [[Rajasthan]] |

image:WLA lacma Celestial Nymph ca 1450 Rajasthan.jpg|Marble Sculpture of female [[yakshi]] in typical curving pose, c. 1450, [[Rajasthan]] |

||

File:Sculpture of Alasa Kanya at Vaital Deul, Bhubaneswar.jpg | [[Baitala Deula]] , [[Odisha]] . |

|||

File:Elephanta tourists.jpg|The Colossal [[trimurti]] at the [[Elephanta Caves]] |

File:Elephanta tourists.jpg|The Colossal [[trimurti]] at the [[Elephanta Caves]] |

||

File:The Hindu deity Vishnu - Indian Art - Asian Art Museum of San Francisco.jpg|Typical medieval frontal standing statue of [[Vishnu]], 950–1150 |

File:The Hindu deity Vishnu - Indian Art - Asian Art Museum of San Francisco.jpg|Typical medieval frontal standing statue of [[Vishnu]], 950–1150 |

||

File:Khajuraho8.jpg| In [[Khajuraho Group of Monuments|Khajuraho]] |

File:Khajuraho8.jpg| In [[Khajuraho Group of Monuments|Khajuraho]] |

||

File: |

File:Muktesvara deula.jpg| In 970 CE [[Muktesvara deula]], [[Odisha]] |

||

File:Ellora cave16 001.jpg| Ellora Cave |

|||

File:Natarajartemple1.jpg|[[Gopuram]] of the [[Thillai Nataraja Temple, Chidambaram]], [[Tamil Nadu]], densely packed with rows of painted statues |

File:Natarajartemple1.jpg|[[Gopuram]] of the [[Thillai Nataraja Temple, Chidambaram]], [[Tamil Nadu]], densely packed with rows of painted statues |

||

</gallery> |

</gallery> |

||

Revision as of 10:05, 15 May 2014

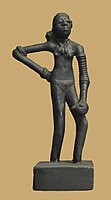

The first known sculpture in the Indian subcontinent is from the Indus Valley civilization (3300–1700 BC), found in sites at Mohenjo-daro and Harappa in modern-day Pakistan. These include the famous small bronze female dancer. However such figures in bronze and stone are rare and greatly outnumbered by pottery figurines and stone seals, often of animals or deities very finely depicted. After the collapse of the Indus Valley civilization there is little record of sculpture until the Buddhist era, apart from a hoard of copper figures of (somewhat controversially) c. 1500 BCE from Daimabad.[2] Thus the great tradition of Indian monumental sculpture in stone appears to begin relatively late, with the reign of Asoka from 270 to 232 BCE, and the Pillars of Ashoka he erected around India, carrying his edicts and topped by famous sculptures of animals, mostly lions, of which six survive.[3] Large amounts of figurative sculpture, mostly in relief, survive from Early Buddhist pilgrimage stupas, above all Sanchi; these probably developed out of a tradition using wood that also embraced Hinduism.[4]

During the 2nd to 1st century BCE in far northern India, in the Greco-Buddhist art of Gandhara from what is now southern Afghanistan and northern Pakistan, sculptures became more explicit, representing episodes of the Buddha’s life and teachings. Although India had a long sculptural tradition and a mastery of rich iconography, the Buddha was never represented in human form before this time, but only through some of his symbols. This may be because Gandharan Buddhist sculpture in modern Afghanistan displays Greek and Persian artistic influence. Artistically, the Gandharan school of sculpture is said to have contributed wavy hair, drapery covering both shoulders, shoes and sandals, acanthus leaf decorations, etc.

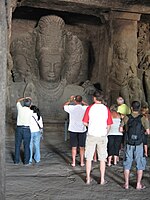

The pink sandstone Hindu, Jain and Buddhist sculptures of Mathura from the 1st to 3rd centuries CE reflected both native Indian traditions and the Western influences received through the Greco-Buddhist art of Gandhara, and effectively established the basis for subsequent Indian religious sculpture.[5] The style was developed and diffused through most of India under the Gupta Empire (c. 320-550) which remains a "classical" period for Indian sculpture, covering the earlier Ellora Caves,[6] though the Elephanta Caves are probably slightly later.[7] Later large scale sculpture remains almost exclusively religious, and generally rather conservative, often reverting to simple frontal standing poses for deities, though the attendant spirits such as apsaras and yakshi often have sensuously curving poses. Carving is often highly detailed, with an intricate backing behind the main figure in high relief. The celebrated bronzes of the Chola dynasty (c. 850–1250) from south India, many designed to be carried in processions, include the iconic form of Shiva as Nataraja,[8] with the massive granite carvings of Mahabalipuram dating from the previous Pallava dynasty.[9]

-

The "dancing girl of Mohenjo Daro", 3rd millennium BCE (replica)

-

Buddha from Sarnath, 5–6th century CE

-

Hindu, Chola period, 1000

-

Baitala Deula , Odisha .

-

The Colossal trimurti at the Elephanta Caves

-

Typical medieval frontal standing statue of Vishnu, 950–1150

-

In Khajuraho

-

In 970 CE Muktesvara deula, Odisha

-

Ellora Cave

-

Gopuram of the Thillai Nataraja Temple, Chidambaram, Tamil Nadu, densely packed with rows of painted statues

Greco-Buddhist art

Greco-Buddhist art is the artistic manifestation of Greco-Buddhism, a cultural syncretism between the Classical Greek culture and Buddhism, which developed over a period of close to 1000 years in Central Asia, between the conquests of Alexander the Great in the 4th century BCE, and the Islamic conquests of the 7th century CE. Greco-Buddhist art is characterized by the strong idealistic realism of Hellenistic art and the first representations of the Buddha in human form, which have helped define the artistic (and particularly, sculptural) canon for Buddhist art throughout the Asian continent up to the present. Though dating is uncertain, it appears that strongly Hellenistic styles lingered in the East for several centuries after they had declined around the Mediterranean, as late as the 5th century CE. Some aspects of Greek art were adopted while others did not spread beyond the Greco-Buddhist area; in particular the standing figure, often with a relaxed pose and one leg flexed, and the flying cupids or victories, who became popular across Asia as apsaras. Greek foliage decration was also influential, with Indian versions of the Corinthian capital appearing.[10]

The origins of Greco-Buddhist art are to be found in the Hellenistic Greco-Bactrian kingdom (250 BCE – 130 BCE), located in today’s Afghanistan, from which Hellenistic culture radiated into the Indian subcontinent with the establishment of the small Indo-Greek kingdom (180 BCE-10 BCE). Under the Indo-Greeks and then the Kushans, the interaction of Greek and Buddhist culture flourished in the area of Gandhara, in today’s northern Pakistan, before spreading further into India, influencing the art of Mathura, and then the Hindu art of the Gupta empire, which was to extend to the rest of South-East Asia. The influence of Greco-Buddhist art also spread northward towards Central Asia, strongly affecting the art of the Tarim Basin and the Dunhuang Caves, and ultimately the sculpted figure in China, Korea, and Japan.[11]

-

Gandhara frieze with devotees, holding plantain leaves, in purely Hellenistic style, inside Corinthian columns, 1st–2nd century CE. Buner, Swat, Pakistan. Victoria and Albert Museum

-

Coin of Demetrius I of Bactria, who reigned circa 200–180 BC and invaded Northern India

-

Buddha head from Hadda, Afghanistan, 3rd–4th centuries

-

Gandhara Poseidon (Ancient Orient Museum)

-

Taller Buddha of Bamiyan, c. 547 AD., in 1963 and in 2008 after they were dynamited and destroyed in March 2001 by the Taliban

-

Statue from a Buddhist monastery 700 AD, Afghanistan

See also

Gallery

-

Marble stone work, Jaisalmer Jain Temple, Rajasthan

-

Seated Ganesha, sandstone sculpture from Rajasthan, India, 9th century, Honolulu Academy of Arts

-

yellow sandstone Sculpture of a Standing deity,11th century CE, Rajasthan

Notes

- ^ "World Heritage List: Konark". UNESCO. Retrieved 25 October 2012.

- ^ Harle, 17–20

- ^ Harle, 22–24

- ^ Harle, 26–38

- ^ Harle, 26–38

- ^ Harle, 87; his Part 2 covers the period

- ^ Harle, 124

- ^ Harle, 301-310, 325-327

- ^ Harle, 276–284

- ^ Boardman, 370–378; Harle, 71–84

- ^ Boardman, 370–378; Sickman, 85–90; Paine, 29–30

References

- Boardman, John ed., The Oxford History of Classical Art, 1993, OUP, ISBN 0198143869

- Harle, J.C., The Art and Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent, 2nd edn. 1994, Yale University Press Pelican History of Art, ISBN 0300062176

- Paine, Robert Treat, in: Paine, R. T. & Soper A, The Art and Architecture of Japan, 3rd ed 1981, Yale University Press Pelican History of Art, ISBN 0140561080

- Sickman, Laurence, in: Sickman L & Soper A, The Art and Architecture of China, Pelican History of Art, 3rd ed 1971, Penguin (now Yale History of Art), LOC 70-125675

Further reading

- Lerner, Martin (1984). The flame and the lotus: Indian and Southeast Asian art from the Kronos collections. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 0870993747.

{{cite book}}: External link in|title= - Welch, Stuart Cary (1985). India: art and culture, 1300-1900. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 9780944142134.

{{cite book}}: External link in|title=