Circumcision and HIV: Difference between revisions

(null edit) - meant to link to: WP:No original research |

Preconscious (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 139: | Line 139: | ||

==Mechanism of action== |

==Mechanism of action== |

||

Experimental evidence supports the theory that [[Langerhans cell]]s (part of the human immune system) in foreskin |

Experimental evidence supports the theory that [[Langerhans cell]]s (part of the human immune system) in foreskin may be a protective factor.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Weiss HA, Dickson KE, Agot K, Hankins CA |title=Male circumcision for HIV prevention: current research and programmatic issues |journal=AIDS |year=2010 |volume=24 Suppl 4 |pages=S61–9 |pmid=21042054 |doi=10.1097/01.aids.0000390708.66136.f4 |url=http://journals.lww.com/aidsonline/Fulltext/2010/10004/Male_circumcision_for_HIV_prevention__current.7.aspx|type= Randomized controlled trial}}</ref> |

||

A research group of Youichi Ogawa et alii <ref>Ogawa, Youichi/Kawamura, Tatsuyoshi/ Kimura, Tetsuya/Ito, Masahiko/ Blauveit, Andrew/ Shimada, Shinji 2009: Gram-positive bacteria enhance HIV-1 susceptibility in Langerhans cells, but not in dendritic cells, via Toll-like receptor activation. In: Blood, 21.5.2009, Vol. 113, Nr. 21, 5157-5166.</ref> confirmed the findings of de Witte et alii, that [[langerin]] protects [[Langerhans cells] from being infected by HIV and other [[STD]]. <ref>Lot de Witte et alii: "Langerin is a natural barrier to HIV-1 transmission by Langerhans cells" http://www.nature.com/nm/journal/v13/n3/abs/nm1541.html</ref> "This study also showed that langerin was involved in capture of HIV and subsequent internalization within Birbeck granules, where it was degraded." However, Oguwa et alii found, "when LCs were exposed to high viral concentrations of HIV, there was significant infection of LCs by R5 virus, followed by viral transmission to T cells." Oguwa et alii also observed, that [[anaerobic bacteria]] do not "enhance HIV susceptibility in LCs". However they conclude, that Gram-positive bacteria components "directly augmented HIV infections in LCs by activating [[TLR2]]. |

|||

==History== |

==History== |

||

Revision as of 08:44, 30 July 2014

This article needs to be updated. (January 2014) |

Epidemiological studies have been conducted to investigate the relationship between male circumcision and HIV infection.[1][2] The WHO and the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) stated that male circumcision is an efficacious intervention for HIV prevention but should be carried out by well trained medical professionals and under conditions of informed consent (parents consent for their infant boys).[3][4][5] The CDC states that circumcision reduces the risk that a man will acquire HIV and other STDs from an infected female partner. [6]

A meta-analysis of data from fifteen observational studies of men who have sex with men found "insufficient evidence that male circumcision protects against HIV infection or other STIs."[7]

Men who have sex with men (MSM)

A 2008 meta-analysis of 53,567 gay and bisexual men (52% circumcised) found that the rate of HIV infection was non-significantly lower among men who were circumcised compared with those who were uncircumcised.[7] For men who engaged primarily in insertive anal sex, a protective effect was observed, but it too was not statistically significant. Observational studies included in the meta-analysis that were conducted prior to the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy in 1996 demonstrated a statistically significant protective effect for circumcised MSM against HIV infection.[7]

Millett et al. (2007) found no association in three major US cities between circumcision and HIV infection among Latino and black men who have sex with men (MSM) . They conclude as follows: "In these cross-sectional data, there was no evidence that being circumcised was protective against HIV infection among black MSM or Latino MSM."[8]

Recommendations

In 2007 the World Health Organization (WHO) held a meeting in Montreux, Switzerland to review the evidence that had accumulated around male circumcision and HIV.[9] The WHO and UNAIDS issued joint recommendations concerning male circumcision and HIV/AIDS.[5] These recommendations are:

- Male circumcision should now be recognized as an efficacious intervention for HIV prevention.

- Promoting male circumcision should be recognized as an additional, important strategy for the prevention of heterosexually acquired HIV infection in men.[4]

Kim Dickson, coordinator of the working group that authored the report, commented:

- Male circumcision "would have greatest impact" in countries where the HIV infection rate among heterosexual males is greater than 15 percent and fewer than 20 percent of males are circumcised.

- WHO further recommends that the procedure must be done by a trained physician.

- Protection is incomplete and men must continue to use condoms and have fewer partners.

- Newly circumcised men should abstain from sex for at least six weeks.[10]

The World Health Organization (WHO) said: "Although these results demonstrate that male circumcision reduces the risk of men becoming infected with HIV, the UN agencies emphasize that it does not provide complete protection against HIV infection. Circumcised men can still become infected with the virus and, if HIV-positive, can infect their sexual partners. Male circumcision should never replace other known effective prevention methods and should always be considered as part of a comprehensive prevention package, which includes correct and consistent use of male or female condoms, reduction in the number of sexual partners, delaying the onset of sexual relations, and HIV testing and counselling."[11]

Others have also expressed concern that some may mistakenly believe they will be fully protected against HIV through circumcision and see circumcision as a safe alternative to other forms of protection, such as condoms.[12][13]

Risk

If proper hygienic procedures are not adhered to, the circumcision operation itself can spread HIV. Brewer et al. (2007)[14] report, "[circumcised] male and female virgins were substantially more likely to be HIV infected than uncircumcised virgins. Among adolescents, regardless of sexual experience, circumcision was just as strongly associated with prevalent HIV infection. However, uncircumcised adults were more likely to be HIV positive than circumcised adults." They concluded: "HIV transmission may occur through circumcision-related blood exposures in eastern and southern Africa."

An interim analysis from the Rakai Health Sciences Program in Uganda suggested that newly circumcised HIV positive men may be more likely to spread HIV to their female partners if they have sexual intercourse before the wound is fully healed. “Because the total number of men who resumed sex before certified wound healing is so small, the finding of increased transmission after surgery may have occurred by chance alone. However, we need to err on the side of caution to protect women in the context of any future male circumcision programme,” said Maria Wawer, the study's principal investigator.[15]

Kalichman et al. (2007) argue that any protective effects circumcision could offer would be partially offset by increased HIV risk behavior, or “risk compensation" including reduction in condom use or increased numbers of sex partners. They note that circumcised men in the South African trial had 18% more sexual contacts than uncircumcised men at follow-up. They also said that because participants were given ongoing risk-reduction counseling and free condoms, it "reduced the utility of these trials for estimating the potential behavioral impact of male circumcision when implemented in a natural setting." They also criticised current models for failing to account for increased HIV risk behaviour. Increased HIV risk behaviour would mean more women would be infected which would consequently increase the risk of men. It would also mean that non-HIV STI's, which have been associated with increased HIV risk, would increase.[16]

The relative risk of HIV infection is 0.42 (95% CI 0.31-0.57),[17] 0.44 (0.33-0.60)[18] and 0.43 (0.32-0.59).[19] (rate of HIV infection in circumcised divided by rate in uncircumcised men). Weiss et al. report that meta-analysis of "as-treated" figures from RCTs reveals a stronger protective effect (0.35; 95% CI 0.24-0.54) than if "intention-to-treat" figures are used.[17] Byakika-Tusiime also estimated a summary relative risk of 0.39 (0.27-0.56) for observational studies, and 0.42 (0.33-0.53) overall (including both observational and RCT data).[19] Weiss et al. report that the estimated relative risk using RCT data was "identical" to that found in observational studies (0.42).[17] Byakika-Tusiime states that available evidence satisfies six of Hill's criteria, and concludes that the results of her analysis "provide unequivocal evidence that circumcision plays a causal role in reducing the risk of HIV infection among men."[19] Mills et al. conclude that circumcision is an "effective strategy for reducing new male HIV infections", but caution that consistently safe sexual practices will be required to maintain the protective effect at the population level.[18] Weiss et al. conclude that the evidence from the trials is conclusive, but that challenges to implementation remain, and will need to be faced.[17]

Mechanism of action

Experimental evidence supports the theory that Langerhans cells (part of the human immune system) in foreskin may be a protective factor.[20] A research group of Youichi Ogawa et alii [21] confirmed the findings of de Witte et alii, that langerin protects [[Langerhans cells] from being infected by HIV and other STD. [22] "This study also showed that langerin was involved in capture of HIV and subsequent internalization within Birbeck granules, where it was degraded." However, Oguwa et alii found, "when LCs were exposed to high viral concentrations of HIV, there was significant infection of LCs by R5 virus, followed by viral transmission to T cells." Oguwa et alii also observed, that anaerobic bacteria do not "enhance HIV susceptibility in LCs". However they conclude, that Gram-positive bacteria components "directly augmented HIV infections in LCs by activating TLR2.

History

Hypotheses and early work

Valiere Alcena has said that a 1986 letter he wrote to the New York State Journal of Medicine was the first time low rates of circumcision in Africa had been linked to the high rate of HIV infection there.[23][24] Aaron J. Fink, a noted advocate of circumcision, also proposed that circumcision could have a preventative role[25]—later that year the New England Journal of Medicine published his letter, "A possible explanation for heterosexual male infection with AIDS".[26][27] Alcena later said that Fink had taken his ideas and got the credit for them.[23]

By 2000, over 40 epidemiological studies had been conducted to investigate the relationship between circumcision and HIV infection.[28] A meta-analysis conducted by researchers at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine examined 27 studies of circumcision and HIV in sub-Saharan Africa and concluded that these showed circumcision to be "associated with a significantly reduced risk of HIV infection" that could form part of a useful public health strategy.[29]

A 2003 systematic review from the Cochrane Collaboration was more cautious. This review of 35 observational studies concluded that while there was an association between circumcision and HIV prevention, the evidence was insufficient to support changes to public health policy.[30] A 2005 review of 37 observational studies expressed reservations about solidity of the conclusion that could be drawn because of possible confounding factors. The authors said that instead three randomized controlled trials then underway in Africa would provide "essential evidence" about the effects of circumcision on preventing HIV.[31]

African trials

Three randomized controlled trials were commissioned as a means to reduce the effect of any confounding factors.[30] Trials took place in South Africa,[26] Kenya[32] and Uganda.[33] Africa has a higher rate of adult HIV infection than anywhere else in the world—a 1989 study had found uncircumcised men there 8.2 times more likely to have HIV.[34]

The first trial to publish, in 2005, was that from South Africa, named ANRS-1265 or the "Orange Farm trial".[9] After 17 months, 20 men had contracted HIV in the circumcised group and 49 in the control group—a finding which led to cessation of the trial on ethical grounds. The trial report concluded that circumcision offered protection against HIV infection "equivalent to what a vaccine of high efficacy would have achieved".[26] Publication sparked an increased interest in the use of circumcision for aids prevention in international health agencies.[9]

The other two African trials were also halted on ethical grounds, again because those in the circumcised group had a lower rate of HIV contraction than the control group.[32] A 2008 meta-analysis of the results of all three trials found that the risk in circumcised males was 0.44 times that in uncircumcised males, and reported that 72 circumcisions would need to be performed to prevent one HIV infection. The authors also stated that using circumcision as a means to reduce HIV infection would, on a national level, require consistently safe sexual practices to maintain the protective benefit.[35]

Society and culture

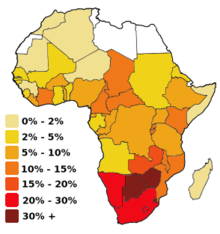

The prevalence of circumcision varies across Africa.[36][37] Studies were conducted to assess the acceptability of promoting circumcision; in 2007, country consultations and planning to scale up male circumcision programmes took place in Botswana, Kenya, Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, Rwanda, South Africa, Swaziland, Uganda, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe.[38]

The UNAIDS/WHO/SACEMA Expert Group on Modelling the Impact and Cost of Male Circumcision for HIV Prevention found "large benefits" of circumcision in settings with high HIV prevalence and low circumcision prevalence. The Group estimated "one HIV infection being averted for every five to 15 male circumcisions performed, and costs to avert one HIV infection ranging from US$150 to US$900 using a 10-y time horizon".[39] McAllister et al. estimated that consistent condom use is 95 times more cost effective than circumcision at reducing the rate of HIV in sub-Saharan Africa;[40] the World Health Organisation states that circumcision is "highly cost-effective" in comparison to other HIV interventions when data from the South African trial are used, but less cost-effective when data from the Ugandan trial are used.[3]

Van Howe et al. criticise the drive to promote circumcision in Africa, asking "Why are circumcision proponents expending so much time and energy promoting mass circumcision to North Americans when their supposed aim is to prevent HIV in Africa? The circumcision rate is declining in the US, especially on the west coast; the two North American national paediatric organisations have elected not to endorse the practice, and the practice’s legality has been questioned in both the medical and legal literature. ‘Playing the HIV card’ misdirects the fear understandably generated in North Americans by the HIV/AIDS pandemic into a concrete action: the perpetuation of the outdated practice of neonatal circumcision."[41]

See also

References

- ^ Krieger JN (May 2011). "Male circumcision and HIV infection risk". World Journal of Urology (Review). 30 (1): 3–13. doi:10.1007/s00345-011-0696-x. PMID 21590467.

- ^ Siegfried N, Muller M, Deeks JJ, Volmink J (2009). Siegfried, Nandi (ed.). "Male circumcision for prevention of heterosexual acquisition of HIV in men". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Review) (2): CD003362. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003362.pub2. PMID 19370585.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Male circumcision: Global trends and determinants of prevalence, safety and acceptability" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2007. Retrieved 2009-03-04.

- ^ a b "New Data on Male Circumcision and HIV Prevention: Policy and Programme Implications" (PDF). World Health Organization. March 28, 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-13.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b "WHO and UNAIDS announce recommendations from expert consultation on male circumcision for HIV prevention". World Health Organisation. March 2007.

- ^ "Male Circumcision". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2013.

- ^ a b c Millett GA, Flores SA, Marks G, Reed JB, Herbst JH (October 2008). "Circumcision status and risk of HIV and sexually transmitted infections among men who have sex with men: a meta-analysis". JAMA (Meta-analysis). 300 (14): 1674–84. doi:10.1001/jama.300.14.1674. PMID 18840841.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ [non-primary source needed]Millett, G.A. (December 2007). "Circumcision status and HIV infection among Black and Latino men who have sex with men in 3 US cities". Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (Research article). 46 (5): 643–50. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e31815b834d. PMID 18043319. Retrieved 2007-07-09.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Taljaard D, Chimbwete C (2009). HIV and Circumcision. Springer. pp. 323–. ISBN 978-1-4419-0306-8.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ "WHO hails circumcision as vital in HIV fight". New Scientist. March 28, 2007. Retrieved 2008-09-18.

- ^ "WHO and UNAIDS Secretariat welcome corroborating findings of trials assessing impact of male circumcision on HIV risk". World Health Organization. February 23, 2007. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- ^ "Male circumcision reduces the risk of becoming infected with HIV, but does not provide complete protection". World Health Organization. December 13, 2006. Retrieved 2006-07-20.

- ^ "Circumcision 'reduces HIV risk'". BBC News. October 25, 2005.

- ^ [non-primary source needed]Brewer, Devon; Potterat, JJ; Roberts Jr, JM; Brody, S (February 2007). "Male and Female Circumcision Associated with Prevalent HIV Infection in Virgins and Adolescents in Kenya, Lesotho, and Tanzania". Annals of Epidemiology (Research article). 17 (3): 217–26. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2006.10.010. PMID 17320788.

- ^ Virginia Differding (March 12, 2007). "Women may be at heightened risk of HIV infection immediately after male partner is circumcised". Aidsmap News. Retrieved 2007-03-14.

- ^ Kalichman, S; Eaton L; Pinkerton S (March 27, 2007). "Circumcision for HIV Prevention: Failure to Fully Account for Behavioral Risk Compensation". PLOS Medicine (Letter). 4 (3): e138. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0040138. PMC 1831748. PMID 17388676. Retrieved 2008-10-08.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c d Weiss HA, Halperin D, Bailey RC, Hayes RJ, Schmid G, Hankins CA (March 2008). "Male circumcision for HIV prevention: from evidence to action?" (PDF). AIDS (Editorial, review). 22 (5): 567–74. doi:10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f3f406. PMID 18316997.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Mills E, Cooper C, Anema A, Guyatt G (July 2008). "Male circumcision for the prevention of heterosexually acquired HIV infection: a meta-analysis of randomized trials involving 11,050 men". HIV Med. 9 (6): 332–5. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1293.2008.00596.x. PMID 18705758.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Byakika-Tusiime J (September 2008). "Circumcision and HIV Infection: Assessment of Causality". AIDS Behav (Meta-analysis). 12 (6): 835–41. doi:10.1007/s10461-008-9453-6. PMID 18800244.

- ^ Weiss HA, Dickson KE, Agot K, Hankins CA (2010). "Male circumcision for HIV prevention: current research and programmatic issues". AIDS (Randomized controlled trial). 24 Suppl 4: S61–9. doi:10.1097/01.aids.0000390708.66136.f4. PMID 21042054.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ogawa, Youichi/Kawamura, Tatsuyoshi/ Kimura, Tetsuya/Ito, Masahiko/ Blauveit, Andrew/ Shimada, Shinji 2009: Gram-positive bacteria enhance HIV-1 susceptibility in Langerhans cells, but not in dendritic cells, via Toll-like receptor activation. In: Blood, 21.5.2009, Vol. 113, Nr. 21, 5157-5166.

- ^ Lot de Witte et alii: "Langerin is a natural barrier to HIV-1 transmission by Langerhans cells" http://www.nature.com/nm/journal/v13/n3/abs/nm1541.html

- ^ a b Alcena, V (19 October 2006). "AIDS in Third World countries". PLOS Medicine (Comment).

- ^ Alcena, V (August 1986). "AIDS in Third World countries". New York State Journal of Medicine (Letter). 86 (8): 446.

- ^ Lindsey, R (1 February 1988). "Circumcision Under Criticism As Unnecessary to Newborn". New York Times.

- ^ a b c Auvert B, Taljaard D, Lagarde E, Sobngwi-Tambekou J, Sitta R, Puren A (November 2005). "Randomized, controlled intervention trial of male circumcision for reduction of HIV infection risk: the ANRS 1265 Trial". PLoS Med. (Randomized controlled trial). 2 (11): e298. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0020298. PMC 1262556. PMID 16231970.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Fink AJ (October 1986). "A possible explanation for heterosexual male infection with AIDS". N. Engl. J. Med. (Letter). 315 (18): 1167. doi:10.1056/nejm198610303151818. PMID 3762636.

- ^ Szabo R, Short RV (June 2000). "How does male circumcision protect against HIV infection?". BMJ (Review). 320 (7249): 1592–4. doi:10.1136/bmj.320.7249.1592. PMC 1127372. PMID 10845974.

- ^ Weiss HA, Quigley MA, Hayes RJ (October 2000). "Male circumcision and risk of HIV infection in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis" (PDF). AIDS (Meta-analysis). 14 (15): 2361–70. doi:10.1097/00002030-200010200-00018. PMID 11089625.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Siegfried N, Muller M, Volmink J; et al. (2003). Siegfried, Nandi (ed.). "Male circumcision for prevention of heterosexual acquisition of HIV in men". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (Review) (3): CD003362. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003362. PMID 12917962.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Siegfried N, Muller M, Deeks J; et al. (March 2005). "HIV and male circumcision--a systematic review with assessment of the quality of studies". The Lancet infectious diseases (Review). 5 (3): 165–73. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(05)01309-5. PMID 15766651.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Bailey RC, Moses S, Parker CB; et al. (February 2007). "Male circumcision for HIV prevention in young men in Kisumu, Kenya: a randomised controlled trial". Lancet (Randomized controlled trial). 369 (9562): 643–56. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60312-2. PMID 17321310.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gray RH, Kigozi G, Serwadda D; et al. (February 2007). "Male circumcision for HIV prevention in men in Rakai, Uganda: a randomised trial". Lancet (Randomized controlled trial). 369 (9562): 657–66. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60313-4. PMID 17321311.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cameron DW, Simonsen JN, D'Costa LJ; et al. (August 1989). "Female to male transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1: risk factors for seroconversion in men". Lancet (Prospective Study). 2 (8660): 403–7. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(89)90589-8. PMID 2569597.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mills E, Cooper C, Anema A, Guyatt G (July 2008). "Male circumcision for the prevention of heterosexually acquired HIV infection: a meta-analysis of randomized trials involving 11,050 men". HIV Med. (Meta-analysis). 9 (6): 332–5. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1293.2008.00596.x. PMID 18705758.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Marck, Jeff (1997). "Aspects of male circumcision in subequatorial African culture history" (PDF). Health Transition Review (Review). 7 (Supplement): 337–60. PMID 10173099. Retrieved 2008-10-16.

- ^ "Male circumcision: global trends and determinants of prevalence, safety and acceptability" (PDF). Who/Unaids. 2007. Retrieved 2008-10-16.

- ^ "Towards Universal access: Scaling up priority HIV/AIDS interventions in the health sector" (PDF). Who/Unaids/Unicef: 75. 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-16.

- ^ UNAIDS/WHO/SACEMA Expert Group on Modelling the Impact and Cost of Male Circumcision for HIV Prevention (2009). "Male Circumcision for HIV Prevention in High HIV Prevalence Settings: What Can Mathematical Modelling Contribute to Informed Decision Making?". PLoS Med (Review). 6 (9): e1000109. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000109. PMC 2731851. PMID 19901974.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Mcallister RG, Travis JW, Bollinger D, Rutiser C, Sundar V (Fall 2008). "The cost to circumcise Africa". International Journal of Men's Health. 7 (3). Men's Studies Press: 307–316. doi:10.3149/jmh.0703.307. ISSN 1532-6306.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: year (link)(Online ISSN: 1933-0278) - ^ Van Howe, Robert (November 2005). "HIV infection and circumcision: cutting through the hyperbole". Journal of the royal society for the promotion of health (Review). 125 (6): 259–65. doi:10.1177/146642400512500607. PMID 16353456.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link)

Further reading

- Akiyama K, Kawamura M, Ogata T, Tanaka E (December 1987). "Retinal vascular loss in idiopathic central serous chorioretinopathy with bullous retinal detachment". Ophthalmology (Review). 94 (12): 1605–9. doi:10.1016/s0161-6420(87)33243-9. PMID 3431830.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Chang LW, Serwadda D, Quinn TC, Wawer MJ, Gray RH, Reynolds SJ (January 2013). "Combination implementation for HIV prevention: moving from clinical trial evidence to population-level effects". Lancet Infect Dis (Review). 13 (1): 65–76. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70273-6. PMC 3792852. PMID 23257232.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Darby R, Van Howe R (October 2011). "Not a surgical vaccine: there is no case for boosting infant male circumcision to combat heterosexual transmission of HIV in Australia". Aust N Z J Public Health (Review). 35 (5): 459–65. doi:10.1111/j.1753-6405.2011.00761.x. PMID 21973253.

- Morris BJ, Bailey RC, Klausner JD; et al. (2012). "Review: a critical evaluation of arguments opposing male circumcision for HIV prevention in developed countries". AIDS Care (Review). 24 (12): 1565–75. doi:10.1080/09540121.2012.661836. PMC 3663581. PMID 22452415.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Morris BJ, Bailey RC, Klausner JD; et al. (2012). "Review: a critical evaluation of arguments opposing male circumcision for HIV prevention in developed countries". AIDS Care (Review). 24 (12): 1565–75. doi:10.1080/09540121.2012.661836. PMC 3663581. PMID 22452415.

- Reed JB, Njeuhmeli E, Thomas AG; et al. (August 2012). "Voluntary medical male circumcision: an HIV prevention priority for PEPFAR". J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. (Review). 60 Suppl 3: S88–95. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e31825cac4e. PMC 3663585. PMID 22797745.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ryan CA, Conly SR, Stanton DL, Hasen NS (August 2012). "Prevention of sexually transmitted HIV infections through the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief: a history of achievements and lessons learned". J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. (Review). 60 Suppl 3: S70–7. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e31825e3149. PMID 22797743.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Uthman OA, Popoola TA, Uthman MM, Aremu O (2010). Van Baal, Pieter H. M (ed.). "Economic evaluations of adult male circumcision for prevention of heterosexual acquisition of HIV in men in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review". PLoS ONE (Review). 5 (3): e9628. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0009628. PMC 2835757. PMID 20224784.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - World Health Organization

- "Voluntary medical male circumcision for HIV prevention". World Health Organization. July 2012. Retrieved January 11, 2014.

- "Global health sector strategy on HIV/AIDS 2011-2015" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2011. Retrieved January 11, 2014.

- "Guideline on the use of devices for adult male circumcision for HIV prevention". World Health Organization. October 2013. Retrieved January 11, 2014.

External links

- "Male circumcision for HIV prevention". World Health Organization. Retrieved January 11, 2014.