Caning in Singapore: Difference between revisions

| Line 131: | Line 131: | ||

==Military caning== |

==Military caning== |

||

In the [[Singapore Armed Forces]] (SAF), a subordinate military court, or the officer in charge of the SAF Detention Barracks, may sentence a serviceman to a maximum of 24 strokes of the cane (10 strokes if the serviceman is below 16)<ref> |

In the [[Singapore Armed Forces]] (SAF), a subordinate military court, or the officer in charge of the SAF Detention Barracks, may sentence a serviceman to a maximum of 24 strokes of the cane (10 strokes if the serviceman is below 16)<ref>Singapore Armed Forces Act section 125(2).</ref> for committing certain military offences or for committing aggravated offences while in the Detention Barracks.<ref>Singapore Armed Forces Act section 119(1).</ref> In all cases, the caning sentence must be approved by the Armed Forces Council before it can be awarded.<ref>Singapore Armed Forces Act section 119(2).</ref> The minimum age for a serviceman to be sentenced to caning is 16 (now 16.5 ''de facto'', since entry into the SAF is restricted to those above that age).<ref>{{cite web|title=Singapore: Caning in the military forces|url=http://www.corpun.com/counsga.htm|website=World Corporal Punishment Research|accessdate=25 January 2015}}</ref> This form of caning is mainly used on recalcitrant teenage conscripts serving [[Conscription in Singapore|full-time National Service]] in the SAF.<ref>{{cite news|title=Murder charge soldiers can be court-martialled|url=http://www.corpun.com/sgar7507.htm|accessdate=25 January 2015|agency=The Straits Times|date=30 July 1975}}</ref> |

||

Military caning is less severe than its civilian counterpart, and is designed not to cause undue bleeding and leave permanent scars. The offender must be certified by a medical officer to be in a fit condition of health to undergo the punishment<ref> |

Military caning is less severe than its civilian counterpart, and is designed not to cause undue bleeding and leave permanent scars. The offender must be certified by a medical officer to be in a fit condition of health to undergo the punishment<ref>Singapore Armed Forces Act section 125(5).</ref> and shall wear "protective clothing" as prescribed.<ref>Singapore Armed Forces Act section 125(6).</ref> The punishment is administered on the buttocks, which are covered by a "protective guard" to prevent cuts.<ref name="counsga" /> The cane used is no more than 6.35 mm in diameter (about half the thickness of the prison/judicial cane).<ref>Singapore Armed Forces Act section 125(4).</ref> During the punishment, the offender is secured in a bent-over position to a trestle similar to the one used for judicial/prison canings.<ref>Singapore Armed Forces (2006). "Pride, Discipline, Honour" (book commemorating 40th anniversary of the SAF Military Police Command).</ref> |

||

==Reformatory caning== |

==Reformatory caning== |

||

Revision as of 18:21, 24 January 2015

| Part of a series on |

| Corporal punishment |

|---|

|

| By place |

| By implementation |

| By country |

| Court cases |

| Politics |

| Campaigns against corporal punishment |

Caning is a widely used form of legal corporal punishment in Singapore. It can be divided into several contexts: judicial, prison, reformatory, military, school, and domestic or private.

Of these, judicial caning, for which Singapore is best known, is the most severe. It is reserved for male convicts under the age of 50, for a wide range of offences under the Criminal Procedure Code, and is also used as a disciplinary measure in prisons. Caning is also a legal form of punishment for delinquent servicemen in the Singapore Armed Forces (SAF) and is conducted in the SAF Detention Barracks. Caning is also used as an official punishment in reform schools.

In a milder form, caning is used to punish male students in primary and secondary schools for serious misbehaviour. The government encourages this but does not allow caning for female students, who instead receive alternative forms of punishment such as detention.

A much smaller cane or other implement is also used by some parents to punish their children for misbehaving. This is allowed in Singapore but not encouraged by the government.

Judicial caning

History

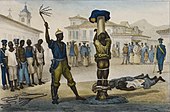

Caning, as a form of legally sanctioned corporal punishment for convicted criminals, was first introduced to Malaya and Singapore by the British Empire in the 19th century. It was formally codified under the Straits Settlements Penal Code Ordinance IV in 1871.[1]

In that era, offences punishable by caning were similar to those punishable by birching or flogging in England and Wales, and included:[1]

- Robbery

- Aggravated forms of theft

- Burglary

- Assault with the intention of sexual abuse

- A second or subsequent conviction of rape

- A second or subsequent offence relating to prostitution

- Living on or trading in prostitution.

Caning remained on the statute book after Malaya declared independence from Britain in 1957, and after Singapore ceased to be part of Malaysia in 1965. Subsequent legislation has been passed by the Parliament of Singapore over the years to increase the minimum strokes an offender receives, and the number of crimes that may be punished with caning.[1]

Legal basis

Sections 325–332 of the Criminal Procedure Code lay down the procedures governing caning. They include the following:

- A male offender between the ages of 18 and 50 who has been certified to be in a fit state of health by a medical officer is liable to be caned.

- The offender shall receive no more than 24 strokes of the cane on any one occasion, irrespective of the total number of offences committed. In other words, a man cannot be sentenced to more than 24 strokes of the cane in a single trial, but he may receive more than 24 strokes if the sentences are given out in separate trials.[2]

- If the offender is under 18, he may receive up to 10 strokes of the cane, but a lighter cane will be used in this case. Boys under 16 may be sentenced to caning only by the High Court and not by the state courts.

- An offender sentenced to death shall not be caned.

- The rattan cane used shall not exceed 1.27 cm in diameter.

Any male convict, whether sentenced to caning or not, may also be caned in prison if he breaks certain prison rules.[3]

- Exemptions

The following groups of people are not liable to be caned for committing offences that may lead to a caning sentence:[4]

- Women

- Men above the age of 50

- Men sentenced to death whose sentences have not been commuted

Offences punishable by caning

Singaporean law allows caning to be ordered for over 30 offences, including hostage-taking/kidnapping, robbery, gang robbery with murder, drug abuse, vandalism, rioting, sexual abuse (molest), and unlawful possession of weapons. Caning is also a mandatory punishment for certain offences such as rape, drug trafficking, illegal money-lending,[5] and for visiting foreigners who overstay their visa by more than 90 days (a measure designed to deter illegal immigrant workers).[6]

While most caning offences were inherited from British law, the Vandalism Act was only introduced after independence in 1966, in what has been argued[7] to be an attempt by the ruling People's Action Party (PAP) to suppress the activities of opposition political parties in the 1960s because their members and supporters vandalised public property with anti-PAP graffiti. Vandalism was originally prohibited by the Minor Offences Act, which made it punishable by a fine of up to S$50 or a week in jail, but did not permit caning.[7]

Contrary to what has sometimes been misreported, the importation of chewing gum is subject only to fines; it is not and has never been an offence punishable by caning.[8]

Statistics

In 1993, the number of caning sentences ordered by the courts was 3,244.[9]

By 2007, this figure had doubled to 6,404, of which about 95% were actually implemented.[10] Since 2007, the number of caning sentences has been experiencing a significant decline year after year, reaching just 2,318 in 2011.

Caning takes place at several establishments around Singapore, notably Changi Prison but also including Queenstown Remand Centre, where Michael P. Fay was caned in 1994. Canings are also administered in the Drug Rehabilitation Centres.

| Year | Number of sentences | Sentences carried out | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1993 | 3,244 | [9] | |

| 2006 | 5,984 | 95% | [11] |

| 2007 | 6,406 | 95% | [10] |

| 2008 | 4,078 | 98.7% | January to September only[12] |

| 2009 | 4,228 | 99.8% | January to November only[13] |

| 2010 | 3,170 | 98.7% | [14] |

| 2011 | 2,318 | 98.9% | [15] |

| 2012 | 2,500 | 88.1% | [16] |

The cane

A rattan[17] cane no more than 1.27 cm in diameter[18] is used for judicial and prison canings. It is at about twice as thick as the canes used in the school and military contexts. The cane is soaked in water overnight to prevent it from splitting and embedding splinters in the wounds.[19] The Prisons Department denies that the cane is soaked in brine, but has said that it is treated with antiseptic before use to prevent infection.[20] A lighter cane is used for juvenile offenders.[21]

Administration procedure

Caning is in practice always ordered in addition to a jail sentence and never as a punishment by itself. It is administered in an enclosed area in the prison, out of view of the public and other inmates. A medical officer and the Superintendent of Prisons are required to be present at every caning session.[22]

The offender is not told in advance when he will be caned; he is notified only on the day his sentence is to be carried out.[23] The medical officer examines him by measuring his blood pressure and other physical conditions to check whether he is medically fit for the caning. If he is certified fit, he proceeds to receive his punishment; if he is certified unfit, he is sent back to the court for his prison term to be extended. A prison officer confirms with him the number of strokes he has been sentenced to.[24]

In practice, the offender is required to strip completely naked for the caning. Once he has removed his clothes, he bends over a padded crossbar on the A-shaped wooden trestle and has his hands and feet secured tightly by leather straps to the trestle, such that he assumes a bent-over position on the trestle at an angle of close to 90° at the hip. Protective padding is tied around his lower back to protect the vulnerable kidney and lower spine area from any strokes that might land off-target.[20] The punishment is administered on his bare buttocks.[25] The caning officer takes up position beside the frame and delivers the number of strokes specified in the sentence at intervals of 10–15 seconds. He is required to exert as much strength as he can muster for each stroke.[20] The offender receives all the strokes in a single caning session – not in instalments.[26]

If during the caning, the medical officer certifies that the offender is not in a fit state of health to undergo the rest of the punishment, the caning must be stopped.[27] The offender will then be sent back to the court for the remaining number of strokes to be remitted or converted to a prison term of no more than 12 months, in addition to the original prison term he was sentenced to.[28]

Medical treatment and the effects

The immediate physical effects of caning have been exaggerated in some accounts; nevertheless, there may be significant physical damage, depending on the number of strokes inflicted. Michael P. Fay said, "The skin did rip open, there was some blood. I mean, let's not exaggerate, and let's not say a few drops or that the blood was gushing out. It was in between the two. It's like a bloody nose."[29] A report by the Singapore Bar Association stated, "The blows are applied with the full force of the jailer's arm. When the rattan hits the bare buttocks, the skin disintegrates, leaving a white line and then a flow of blood."[30] More profuse bleeding may, however, occur in the case of a larger number of strokes.

Men who have been caned before described the pain they experienced as "unbearable" and "excruciating". A recipient of 10 strokes even said, "The pain was beyond description. If there is a word stronger than excruciating, that should be the word to describe it".[31]

After the caning, the inmate is released from the trestle and receives medical treatment. Antiseptic lotion (gentian violet) is applied.[32] The wounds take between a week and a month to heal, and the marks are indelible.[33]

Notable cases

- Michael P. Fay, an American teenager whose conviction for vandalism and sentence of six strokes of the cane attracted worldwide publicity and sparked off a minor diplomatic crisis between Singapore and the United States. The Singaporean government reduced Fay's sentence from six to four strokes. Fay was caned on 5 May 1994 in Queenstown Remand Prison.

- Dickson Tan Yong Wen, a Singaporean who received three more strokes than he was sentenced to because of an administrative error. He was sentenced on 28 February 2007 to nine months in jail and five strokes of the cane for two offences involving abetting an illegal moneylender to harass a debtor. However, he received eight strokes on 29 March 2007.[34] Tan sought S$3 million from the government in compensation but was rejected. He did receive some compensation after negotiations, but the amount was kept secret.[35]

- Dave Teo, a Singaporean Full Time National Serviceman who made headlines in Singapore when he went absent without official leave (AWOL) on 2 September 2007 from an army camp with a SAR 21 assault rifle. He was arrested by the police at Cathay Cineleisure Orchard with the rifle, eight 5.56mm rounds, and a knife in his possession. Teo was sentenced in July 2008 to nine years and two months imprisonment and 18 strokes of the cane under multiple charges under the Arms Offences Act.[36]

- Oliver Fricker, a Swiss national who was sentenced on 25 June 2010 to five months imprisonment and three strokes of the cane for breaking into the SMRT Trains Changi Depot and vandalising an MRT train by spraypainting it.[37]

- Two Taiwanese nationals, Su Wei Ying and Wu Wei Chun, were sentenced in September 2010 to 21 and 24 months jail respectively, and both received 15 strokes of the cane each for loansharking offences. Another Taiwanese national, Chen Ci Fan, was sentenced in January 2011 to 46 months jail and six strokes of the cane, also in connection with loansharking.[38]

Differences between judicial caning in Singapore and in Malaysia

- Juveniles sentenced to caning: In Singapore, only the High Court may order the caning of boys under 16. In Malaysia, local courts may do so.[39]

- Age limit of 50: In Singapore, men above the age of 50 cannot be sentenced to caning. In Malaysia, however, the law was amended in 2006 such that convicted rapists above the age of 50 may still be sentenced to caning. In 2008, a 56-year-old man was sentenced to 57 years jail and 12 strokes of the cane for rape.[40]

- Terminology: In Singapore, in both legislation and press reports, the term "caning" is used to describe the punishment. In Malaysia, the term "caning" is often used informally, while the phrases "strokes of the cane" and "strokes of the rotan" are used interchangeably, but the correct official term is "whipping" in accordance with traditional British legislative terminology.[39]

- Dimensions of the cane: The cane used in Malaysia is marginally smaller than the one used in Singapore but there are no discernible differences when first-person accounts from both countries are compared. In Malaysia, a smaller cane is used for white-collar offenders. There are no reports of any such distinction being made in Singapore.[39]

- Modus operandi: The trestle used in Singapore is not the same as the A-shaped frame used in Malaysia. In Singapore, the offender bends over on the trestle with his feet together, and has protective padding secured around his lower back to protect the kidney and lower spine area from strokes that land off-target. In Malaysia, the offender stands upright at the frame with his feet apart, and has a special protective "shield" tied around his lower body to cover the lower back and upper thighs while leaving the buttocks exposed.[39][41]

Prison caning

Men serving time in prison but have not been sentenced to caning earlier (in a court of law) are still liable to be caned in prison if they violate certain prison rules.

A Superintendent of Prisons may impose corporal punishment not exceeding 12 strokes of the cane for aggravated prison offences[42] after due inquiry at a "mini-court" inside the prison, during which the prisoner is given an opportunity to hear the charge and evidence against him and present his defence.[43] The Prisons Director must approve the punishment before it can be carried out. It is administered in the same manner as judicial caning.

Inmates of Drug Rehabilitation Centres may be caned in the same way.

In 2008, the procedure was revised to introduce a review of each prison caning sentence by an independent external panel.[44]

Military caning

In the Singapore Armed Forces (SAF), a subordinate military court, or the officer in charge of the SAF Detention Barracks, may sentence a serviceman to a maximum of 24 strokes of the cane (10 strokes if the serviceman is below 16)[45] for committing certain military offences or for committing aggravated offences while in the Detention Barracks.[46] In all cases, the caning sentence must be approved by the Armed Forces Council before it can be awarded.[47] The minimum age for a serviceman to be sentenced to caning is 16 (now 16.5 de facto, since entry into the SAF is restricted to those above that age).[48] This form of caning is mainly used on recalcitrant teenage conscripts serving full-time National Service in the SAF.[49]

Military caning is less severe than its civilian counterpart, and is designed not to cause undue bleeding and leave permanent scars. The offender must be certified by a medical officer to be in a fit condition of health to undergo the punishment[50] and shall wear "protective clothing" as prescribed.[51] The punishment is administered on the buttocks, which are covered by a "protective guard" to prevent cuts.[52] The cane used is no more than 6.35 mm in diameter (about half the thickness of the prison/judicial cane).[53] During the punishment, the offender is secured in a bent-over position to a trestle similar to the one used for judicial/prison canings.[54]

Reformatory caning

Caning is used as a form of legal corporal punishment in reformatories, such as the Singapore Boys' Home and Singapore Girls' Home, which house juvenile delinquents up to the age of 16.[55][56]

The Managers of these institutions are given the authority to impose caning on delinquents who have committed offences similar to those punishable by caning in ordinary secondary schools. A maximum of up to 10 strokes of the cane may be inflicted.[55][56] The type of cane used must be approved by the Director before use,[55][56] but no details are provided on the dimensions of the cane, and it is assumed that the cane is similar to the one used in secondary schools. The punishment is administered in private.[55][56] Boys may be caned on the palm of the hand or on the buttocks over clothing.[55][56] Girls may be caned on the palm of the hand only,[55][56] and this is the only form of official corporal punishment in Singapore that may be applied to females.

School caning

Caning is also used as a form of corporal punishment in primary and, especially, secondary schools, and rarely in one or two post-secondary colleges, to maintain strict discipline in school. This is applicable only to male students; it is illegal to cane girls.[57] The punishment is administered formally along traditional British lines, typically in the form of a predetermined number of vigorous cuts across the seat of the student's trousers as he bends over a desk or chair.

The Ministry of Education encourages schools to punish boys by caning for serious offences such as fighting, smoking, cheating, gangsterism, vandalism, defiance and truancy.[58] Students may also be caned for repeated cases of more minor offences, such as being late repeatedly in a term. The punishment may be administered only by the Principal or Vice-Principal, or by a specially designated and trained Discipline Master. At most schools, caning comes after detention but before suspension in the hierarchy of penalties.[59] Some schools use a demerit points system, whereby students receive a mandatory caning after accumulating a certain number of demerit points for a wide range of offences.[59]

Under government regulations, the punishment should not exceed a maximum of six strokes, and can only be administered on the palm of the hand or on the buttocks over clothing, using a light rattan cane.[57] The majority of the canings range from one to three very hard strokes, applied to the seat of the boy's trousers or shorts.[59] Canings on the hand are rarely implemented, but one notable exception is Saint Andrew's Secondary School, where students may be caned on the palm for less serious offences.[60]

Canings in schools may be classified as:

- Private caning (this is the most frequent kind): The student is caned in the school office, in the presence of the Principal/Vice-Principal and another member of the staff.

- Class caning: The student is caned in front of his class.

- Public caning: The student is caned in front of an assembly of the whole school population, to serve as a warning to potential offenders as well as to shame the student. This punishment is usually reserved for serious offences like fighting, smoking or vandalism.

- Others: There can be intermediate levels between a "class caning" and a "public caning". Some schools give these special names, such as "a cohort caning" (in front of all classes of the offending pupil's year) and "a consortium caning" (in front of all the lower secondary, or all the upper secondary, or certain streams of classes within certain year levels).

School caning is a solemn and formal ceremony. Before the caning, the Principal/Discipline Master usually explains the student's offence to the audience. Next, a protective item (a book or a file) is tucked into the boy's trouser waistband to protect the lower back from strokes that land off-target.[59] He is directed to bend over a table or a chair, with his buttocks pushed slightly up and back. In this position, the boy is caned across the seat of his trousers or shorts according to the number of strokes prescribed. He normally experiences superficial bruises and weals for some days after the punishment.[59]

Certain schools have special practices for caning, such as making the student change into physical education (PE) attire (because PE shorts are apparently thinner than the uniform trousers/shorts) for the punishment. Some schools require the student to read out a public apology before receiving his strokes.

Boys of any age from 6 to 19 may be caned, but the majority of canings are of secondary school students aged 14–16 inclusive.[59] The Ministry of Education recommends that the student receive counselling before or after his caning.

Routine school canings are naturally not normally publicised, so cases only get reported in the press in rare special cases.[61][62][63][64][65][66]

Parental caning

Caning is used as a form of punishment in the home for children (both boys and girls) and is usually meted out by their parents, the most common offences being disobedience and lying.[67] This form of punishment is legal in Singapore, but not particularly encouraged by the authorities, and parents are likely to be charged with child abuse if the child is injured.

The Singapore domestic cane (for children, not to be confused with judicial cane) is a thin, rattan cane (~65 cm) with a plastic hook at the end, which comes in a variety of colours. They are available in grocery shops in neighbourhoods, and are used for the purpose of disciplining children and adolescents at home. Each cane costs about 50 Singapore cents, with best sales during times when students prepare for examinations.[68]

Sometimes parents use other implements such as the handle of a feather-duster (made of rattan), rulers or even clothes hangers. The misbehaving child is usually caned on the thighs, calves, buttocks or palms. This type of caning usually leaves the child with cane marks that will fade within days.

According to a survey conducted by The Sunday Times in January 2009, out of the 100 parents surveyed, 57 said that caning was an acceptable form of punishment and they had used it on their children.[69]

Objections to corporal punishment

Amnesty International has condemned the practice of judicial caning in Singapore as "cruel, inhuman or degrading punishment".[70] It is also regarded by some international observers as a violation of Article 1 in the United Nations Convention Against Torture. However, Singapore is not signatory to the Convention.[71] Human Rights Watch also objects to the practice of caning.[citation needed]

In arts and media

Media

- Behind Bars (Chinese: 铁狱雷霆; pinyin: Tiě Yù Léi Tíng; Iron Prison and Thunder), a 1991 Singaporean television series produced by the Singapore Broadcasting Corporation in collaboration with Changi Prison. The drama portrays the lives of prison officers and convicts in prison. There is a brief scene about judicial caning in one of the episodes.

- One More Chance (Chinese: 3个好人; pinyin: Sān Gè Hǎo Rén; Three Good Men),[72] a 2005 Singaporean film by Jack Neo which portrays the lives of three convicts in prison. It also reflects the social stigma towards ex-offenders. A judicial caning scene is featured in the film in which one of the three convicts (played by Henry Thia) receives his caning sentence of six strokes. The scene is not featured explicitly and only the audio is heard in place of visual images.

- I Not Stupid Too (Chinese: 小孩不笨2; pinyin: Xiǎohái Bù Bèn Èr; The Children Are Not Stupid Part II),[73] a 2006 Singaporean film by Jack Neo which reflects the lives of three ordinary Singaporean youngsters in school and their relationships with their families. One of the main characters, Tom Yeo (played by Shawn Lee), is publicly caned in school for hitting his teacher. The caning scene is graphically portrayed, with the young man bending over a desk on stage in the school hall to receive three very hard strokes across the seat of his trousers in front of the assembled student body. This faithfully reproduced the procedure used in real life at the school where the scene was filmed, Presbyterian High School. However, it should be noted that a protective item is placed to protect his spine in case of strokes that land off-target. The public caning issue sparked off a debate in which it became apparent that some members of the Singaporean public did not realise that corporal punishment is widely used in secondary schools.

- The Homecoming (Chinese: 十三鞭; pinyin: Shí Sān Biān; Thirteen Strokes),[74] a 2007 Singaporean television series produced by MediaCorp. In the drama, four men were convicted of arson in their youth and sentenced to imprisonment and three strokes of caning each. One of them (played by Rayson Tan) received one more stroke than either of his three friends, supposedly for being the mastermind. Several years later when he becomes a successful lawyer, he sets off to find out who betrayed him and takes his revenge. The caning scene is featured briefly in flashbacks.

- Don't Stop Believin' featured Junliang (played by Xu Bin) being accused of molesting Jessie. He was then caned three strokes by his father, who is also the school's discipline master, Zhong Guo An (played by Brandon Wong), until Jessie came to the assembly hall shouting that he is innocent.

- Ilo Ilo, a 2013 Singaporean family film directed by Anthony Chen. In one scene, the main character Jiale (played by boy actor Koh Jia Ler) receives a public caning in school for fighting with his classmate.

Literature

- The Caning of Michael Fay: The Inside Story by a Singaporean (1994),[75][76] a documentary book by Gopal Baratham published in the wake of the controversial caning of Michael P. Fay. It concentrates on the personal aspects, the punishment and the sociology of caning in Singapore. The book includes some descriptions of caning and photographs of its results, as well as two personal interviews with men who had been caned before.

See also

References

- ^ a b c "Judicial Caning in Singapore, Malaysia and Brunei #The History of Caning in Singapore, Malaysia and Brunei". World Corporal Punishment Research. September 2012. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- ^ Thomas, Sujin (12 December 2008). "24-stroke caning cap to be formalised". The Straits Times. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ^ Prisons Act section 71.

- ^ Criminal Procedure Code section 325(1).

- ^ "Singapore: Judicial and prison caning: Table of offences for which caning is available". World Corporal Punishment Research. 2011. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ^ Immigration Act section 15(3b).

- ^ a b Rajah, Jothie (April 2012). Authoritarian Rule of Law: Legislation, Discourse and Legitimacy in Singapore. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107634169.

- ^ Control of Manufacture Act sections 8–9.

- ^ a b "Singapore Human Rights Practices, 1994". Electronic Research Collections. U.S. Department of State. February 1995. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ^ a b "Singapore". U.S. Department of State. Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor. 11 March 2008. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ^ "Singapore". U.S. Department of State. Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor. 6 March 2007. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ^ "2008 Human Rights Report: Singapore". U.S. Department of State. Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor. 25 February 2009. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ^ "2009 Human Rights Report: Singapore". U.S. Department of State. Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor. 11 March 2010. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ^ "2010 Human Rights Report: Singapore". U.S. Department of State. Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor. 8 April 2011. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ^ "2011 Human Rights Report: Singapore". U.S. Department of State. Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor. 24 May 2012. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ^ "Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 2012: Singapore". U.S. Department of State. Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ^ Prisons Regulations section 139(1).

- ^ Criminal Procedure Code section 329(3).

- ^ Raman, P.M. (13 September 1974). "Branding the Bad Hats for Life". The Straits Times. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- ^ a b c "Judicial Caning in Singapore, Malaysia and Brunei #Procedure in Detail". World Corporal Punishment Research. September 2012. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ^ Criminal Procedure Code section 329(4).

- ^ Prisons Regulations section 98(1).

- ^ "'No advance notice' for caning". The Straits Times. 4 May 1994. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- ^ John, Arul; Chan, Crystal (1 July 2007). "Prisoners given chance to confirm sentence beforehand". The New Paper. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ^ Prisons Regulations section 139(2).

- ^ Criminal Procedure Code section 330(1).

- ^ Criminal Procedure Code section 331(2).

- ^ Criminal Procedure Code section 332.

- ^ "Fay describes caning, seeing resulting scars". Los Angeles Times. Reuters. 26 June 1994. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- ^ "Judicial Caning in Singapore, Malaysia and Brunei #The Immediate Physical Effects". World Corporal Punishment Research. September 2012. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ^ "Judicial Caning in Singapore, Malaysia and Brunei #Descriptions of the Experience by Men Who Have Been Caned". World Corporal Punishment Research. September 2012. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ^ "Judicial Caning in Singapore, Malaysia and Brunei #Medical Treatment". World Corporal Punishment Research. September 2012. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ^ "Judicial Caning in Singapore, Malaysia and Brunei #After Effects: The Healing of the Wounds". World Corporal Punishment Research. September 2012. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ^ "3 extra strokes for prisoner: Govt regrets error". The Straits Times. 1 July 2007. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ^ Vijayan, K.C. (20 August 2008). "Caning error: Ex-inmate accepts mediated settlement". The Straits Times. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ^ "Judge tells soldier who took rifle out of camp: 'My heart hurts for you'". The Straits Times. 8 July 2008. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ^ Chong, Elena (8 July 2008). "Swiss vandal gets 5 months, 3 strokes". The Straits Times. Retrieved 26 June 2010.

- ^ "Another Taiwanese loansharking offender ordered to be jailed, caned". Today, Singapore. 13 January 2011. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ^ a b c d "Judicial Caning in Singapore, Malaysia and Brunei #Some Differences Between Singapore and Malaysia". World Corporal Punishment Research. September 2012. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ^ "57 years jail and 12 strokes for raping relative". The Star. 30 April 2008. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- ^ "Judicial Caning in Singapore, Malaysia and Brunei #Apparatus Used". World Corporal Punishment Research. September 2012. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ^ Prisons Act section 71.

- ^ Prisons Act section 75.

- ^ Teh, Joo Lin (15 September 2008). "New check on punishing prisoners". The Straits Times. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ^ Singapore Armed Forces Act section 125(2).

- ^ Singapore Armed Forces Act section 119(1).

- ^ Singapore Armed Forces Act section 119(2).

- ^ "Singapore: Caning in the military forces". World Corporal Punishment Research. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ^ "Murder charge soldiers can be court-martialled". The Straits Times. 30 July 1975. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ^ Singapore Armed Forces Act section 125(5).

- ^ Singapore Armed Forces Act section 125(6).

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

counsgawas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Singapore Armed Forces Act section 125(4).

- ^ Singapore Armed Forces (2006). "Pride, Discipline, Honour" (book commemorating 40th anniversary of the SAF Military Police Command).

- ^ a b c d e f Children and Young Persons (Remand Home) Regulations

- ^ a b c d e f Children and Young Persons (Licensing of Homes) Regulations 2011

- ^ a b Section 88, Education (Schools) Regulations.

- ^ Speech by Mr Tharman Shanmugaratnam, Acting Minister for Education, 14 May 2004.

- ^ a b c d e f "Corporal punishment in Singapore schools". World Corporal Punishment Research. January 2012. Retrieved 2012-01-31.

- ^ http://www.saintandrewsschool.info/user_upload/department/Discipline_Rule_Book_2012.pdf

- ^ Liew Hanqing; Tan, Pearly; Tan, Audrey (3 May 2009). "New students warned to avoid bully group". The New Paper. Singapore.

- ^ "Students distressed by public canings just days before exams". AsiaOne.com. Singapore. 13 October 2009.

- ^ Bharwani, Veena (29 January 2008). "2 students caught taking 'upskirt' pics of teacher". MyPaper. Singapore.

- ^ Liaw Wy-Cin (23 April 2007). "'Gangster school' fights back with lots of heart". The Straits Times. Singapore.

- ^ Tan, Valarie (26 January 2006). "Schools left to decide on students' discipline: Education Ministry". Channel News Asia. Singapore.

- ^ Jessica Lim and Tracy Sua (14 April 2006). "Schoolboy punched, jaw fractured". The Straits Times. Singapore.

- ^ Mathi, Braema; Andrianie, Siti (11 April 1999). "Spare your child the rod? No.". The Sunday Times (Singapore).

- ^ Mathi, Braema; Andrianie, Siti (11 April 1999). "Kids say: What works for them". The Sunday Times (Singapore).

- ^ Sudderuddin, Shuli (13 September 2009). "To cane or not to cane...". Asiaone (Singapore).

- ^ Amnesty International Report 2008: Singapore.

- ^ "Status of Ratifications, Office of the United Nations High Commission of Human Rights".

- ^ San ge hao ren at IMDb

- ^ Xiaohai bu ben 2 at IMDb

- ^ Teo, Wendy (3 April 2007). "Rayson Tan bares his bum for the first time in new Channel 8 drama, only to become...The butt of jokes". The New Paper (Singapore).

- ^ Baratham, Gopal (1994). The Caning of Michael Fay. Singapore: KRP Publications. ISBN 981-00-5747-4

- ^ Review of this book at World Corporal Punishment Research.

- ^ Asad Latif (1994). The Flogging of Singapore: The Michael Fay Affair. Singapore: Times Books International. ISBN 981-204-530-9

- ^ Review of this book at World Corporal Punishment Research.