Menstruation: Difference between revisions

m clean up using AWB |

m →Onset and frequency: Removed duplicate information. |

||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

==Onset and frequency== |

==Onset and frequency== |

||

[[File:Lining of Uterine Wall.jpg|thumb|Diagram illustrating how the [[endometrium|uterus lining]] builds up and breaks down during the menstrual cycle.]] |

[[File:Lining of Uterine Wall.jpg|thumb|Diagram illustrating how the [[endometrium|uterus lining]] builds up and breaks down during the menstrual cycle.]] |

||

The first menstrual period occurs after the onset of pubertal growth, and is called [[menarche]]. The average age of menarche is 12 to 15.<ref name=Jones2011/><ref>{{Cite journal | last1 = Karapanou | first1 = O. | last2 = Papadimitriou | first2 = A. | title = Determinants of menarche. | journal = Reprod Biol Endocrinol | volume = 8 | issue = | page = 115 | month = | year = 2010 | doi = 10.1186/1477-7827-8-115 | PMID = 20920296 }}</ref> However, it may start as early as eight.<ref name=Women2014Men/> The average age of the first period is generally later in the [[developing world]], and earlier in the [[developed world]].<ref name=Diaz2006 |

The first menstrual period occurs after the onset of pubertal growth, and is called [[menarche]]. The average age of menarche is 12 to 15.<ref name=Jones2011/><ref>{{Cite journal | last1 = Karapanou | first1 = O. | last2 = Papadimitriou | first2 = A. | title = Determinants of menarche. | journal = Reprod Biol Endocrinol | volume = 8 | issue = | page = 115 | month = | year = 2010 | doi = 10.1186/1477-7827-8-115 | PMID = 20920296 }}</ref> However, it may start as early as eight.<ref name=Women2014Men/> The average age of the first period is generally later in the [[developing world]], and earlier in the [[developed world]].<ref name=Diaz2006/> The average age of menarche has changed little in the United States since the 1950s.<ref name=Diaz2006/> |

||

Menstruation is the most visible phase of the menstrual cycle and its beginning is used as the marker between cycles. The first day of menstrual bleeding is the date used for the last menstrual period (LMP). The typical length of time between the first day of one period and the first day of the next is 21 to 45 days in young women, and 21 to 31 days in adults (an average of 28 days).<ref name=Women2014Men/><ref name=Diaz2006/> |

Menstruation is the most visible phase of the menstrual cycle and its beginning is used as the marker between cycles. The first day of menstrual bleeding is the date used for the last menstrual period (LMP). The typical length of time between the first day of one period and the first day of the next is 21 to 45 days in young women, and 21 to 31 days in adults (an average of 28 days).<ref name=Women2014Men/><ref name=Diaz2006/> |

||

Revision as of 02:18, 13 June 2016

Menstruation, also known as a period or monthly,[1] is the regular discharge of blood and mucosal tissue from the inner lining of the uterus through the vagina.[2] Up to 80% of women report having some symptoms prior to menstruation.[3] Common signs and symptoms include acne, tender breasts, bloating, feeling tired, irritability, and mood changes.[4] These may interfere with normal life, therefore qualifying as premenstrual syndrome, in 20 to 30% of women. In 3 to 8%, symptoms are severe.[3]

The first period usually begins between twelve and fifteen years of age, a point in time known as menarche.[1] However, periods may occasionally start as young as eight years old and still be considered normal.[2] The average age of the first period is generally later in the developing world, and earlier in the developed world. The typical length of time between the first day of one period and the first day of the next is 21 to 45 days in young women, and 21 to 31 days in adults (an average of 28 days).[2][5] Menstruation stops occurring after menopause, which usually occurs between 45 and 55 years of age.[6] Bleeding usually lasts around 2 to 7 days.[2]

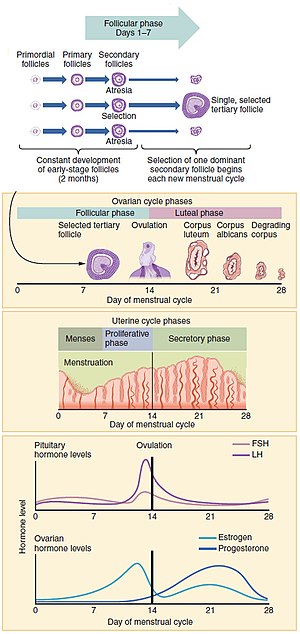

The menstrual cycle occurs due to the rise and fall of hormones. This cycle results in the thickening of the lining of the uterus, and the growth of an egg, (which is required for pregnancy). The egg is released from an ovary around day fourteen in the cycle; the thickened lining of the uterus provides nutrients to an embryo after implantation. If pregnancy does not occur, the lining is released in what is known as menstruation.[2]

A number of problems with menstruation may occur. A lack of periods, known as amenorrhea, is when periods do not occur by age 15 or have not occurred in 90 days. Periods also stop during pregnancy and typically do not resume during the initial months of breastfeeding. Other problems include painful periods and abnormal bleeding such as bleeding between periods or heavy bleeding.[2] Menstruation in other animals occurs in primates, such as apes and monkeys, as well as bats and the elephant shrew.[7][8]

Onset and frequency

The first menstrual period occurs after the onset of pubertal growth, and is called menarche. The average age of menarche is 12 to 15.[1][9] However, it may start as early as eight.[2] The average age of the first period is generally later in the developing world, and earlier in the developed world.[5] The average age of menarche has changed little in the United States since the 1950s.[5]

Menstruation is the most visible phase of the menstrual cycle and its beginning is used as the marker between cycles. The first day of menstrual bleeding is the date used for the last menstrual period (LMP). The typical length of time between the first day of one period and the first day of the next is 21 to 45 days in young women, and 21 to 31 days in adults (an average of 28 days).[2][5]

Perimenopause is when fertility in a female declines, and menstruation occurs less regularly in the years leading up to the final menstrual period, when a female stops menstruating completely and is no longer fertile. The medical definition of menopause is one year without a period and typically occurs between 45 and 55 in Western countries.[6][10]: p. 381

During pregnancy and for some time after childbirth, menstruation does not occur; this state is known as amenorrhoea. If menstruation has not resumed, fertility is low during lactation. The average length of postpartum amenorrhoea is longer when certain breastfeeding practices are followed; this may be done intentionally as birth control.

Health effects

In most women, various physical changes are brought about by fluctuations in hormone levels during the menstrual cycle. This includes muscle contractions of the uterus (menstrual cramping) that can precede or accompany menstruation. Some may notice water retention, changes in sex drive, fatigue, breast tenderness, or nausea. Breast swelling and discomfort may be caused by water retention during menstruation.[11] Usually, such sensations are mild, and some females notice very few physical changes associated with menstruation. A healthy diet, reduced consumption of salt, caffeine and alcohol, and regular exercise may be effective for women in controlling some symptoms.[12] Severe symptoms that disrupt daily activities and functioning may be diagnosed as premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Symptoms before menstruation are known as premenstrual molimina.

Cramps

Many women experience painful cramps, also known as dysmenorrhea, during menstruation.[citation needed] Pain results from ischemia and muscle contractions. Spiral arteries in the secretory endometrium constrict, resulting in ischemia to the secretory endometrium. This allows the uterine lining to slough off. The myometrium contracts spasmodically in order to push the menstrual fluid through the cervix and out of the vagina. The contractions are mediated by a release of prostaglandins.

Painful menstrual cramps that result from an excess of prostaglandin release are referred to as primary dysmenorrhea. Primary dysmenorrhea usually begins within a year or two of menarche, typically with the onset of ovulatory cycles.[13] Treatments that target the mechanism of pain include non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and hormonal contraceptives. NSAIDs inhibit prostaglandin production. With long-term treatment, hormonal birth control reduces the amount of uterine fluid/tissue expelled from the uterus. Thus resulting in shorter, less painful menstruation.[14] These drugs are typically more effective than treatments that do not target the source of the pain (e.g. acetaminophen).[15] Risk factors for primary dysmenorrhea include: early age at menarche, long or heavy menstrual periods, smoking, and a family history of dysmenorrhea.[13] Regular physical activity may limit the severity of uterine cramps.[13]

For many women, primary dysmenorrhea gradually subsides in late second generation. Pregnancy has also been demonstrated to lessen the severity of dysmenorrhea, when menstruation resumes. However, dysmenorrhea can continue until menopause. 5–15% of women with dysmenorrhea experience symptoms severe enough to interfere with daily activities.[13]

Secondary dysmenorrhea is the diagnosis given when menstruation pain is a secondary cause to another disorder. Conditions causing secondary dysmenorrhea include endometriosis, uterine fibroids, and uterine adenomyosis. Rarely, congenital malformations, intrauterine devices, certain cancers, and pelvic infections cause secondary dysmenorrhea.[13] Symptoms include pain spreading to hips, lower back and thighs, nausea, and frequent diarrhea or constipation.[16] If the pain occurs between menstrual periods, lasts longer than the first few days of the period, or is not adequately relieved by the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or hormonal contraceptives, women should be evaluated for secondary causes of dysmenorrhea.[10]: p. 379

When severe pelvic pain and bleeding suddenly occur or worsen during a cycle, the woman or girl should be evaluated for ectopic pregnancy and spontaneous abortion. This evaluation begins with a pregnancy test and should be done as soon as unusual pain begins, because ectopic pregnancies can be life‑threatening.[17]

In some cases, stronger physical and emotional or psychological sensations may interfere with normal activities, and include menstrual pain (dysmenorrhea), migraine headaches, and depression. Dysmenorrhea, or severe uterine pain, is particularly common for young females (one study found that 67.2% of girls aged 13–19 have it).[18]

The medications in the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) class are commonly used to relieve menstrual cramps. Some herbs are also claimed to help.

Mood and behavior

Some women experience emotional disturbances starting one or two weeks before their period, and stopping soon after the period has started.[4] Symptoms may include mental tension, irritability, mood swings, and crying spells. Problems with concentration and memory may occur.[4] There may also be depression or anxiety.[4]

This is part of premenstrual syndrome (PMS) and is estimated to occur in 20 to 30% of women. In 3 to 8% it is severe.[3]

More severe symptoms of anxiety or depression may be signs of premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD). Rarely, in individuals who are susceptible, menstruation may be a trigger for menstrual psychosis.

Bleeding

The average volume of menstrual fluid during a monthly menstrual period is 35 milliliters (2.4 tablespoons of menstrual fluid) with 10–80 milliliters (1–6 tablespoons of menstrual fluid) considered typical. Menstrual fluid is the correct name for the flow, although many people prefer to refer to it as menstrual blood. Menstrual fluid contains some blood, as well as cervical mucus, vaginal secretions, and endometrial tissue. Menstrual fluid is reddish-brown, a slightly darker color than venous blood.[10]: p. 381

Unless a woman has a bloodborne illness, menstrual fluid is harmless. No toxins are released in menstrual flow, as this is a lining that must be pure and clean enough to have nurtured a baby. Menstrual fluid is no more dangerous than regular blood.

About half of menstrual fluid is blood. This blood contains sodium, calcium, phosphate, iron, and chloride, the extent of which depends on the woman. As well as blood, the fluid consists of cervical mucus, vaginal secretions, and endometrial tissue. Vaginal fluids in menses mainly contribute water, common electrolytes, organ moieties, and at least 14 proteins, including glycoproteins.[19]

Many mature females notice blood clots during menstruation. These appear as clumps of blood that may look like tissue. If there are questions (for example, was there a miscarriage?), examination under a microscope can confirm if it was endometrial tissue or pregnancy tissue (products of conception) that was shed.[20] Sometimes menstrual clots or shed endometrial tissue is incorrectly thought to indicate an early-term miscarriage of an embryo. An enzyme called plasmin – contained in the endometrium – tends to inhibit the blood from clotting.

The amount of iron lost in menstrual fluid is relatively small for most women.[21] In one study, premenopausal women who exhibited symptoms of iron deficiency were given endoscopies. 86% of them actually had gastrointestinal disease and were at risk of being misdiagnosed simply because they were menstruating.[22] Heavy menstrual bleeding, occurring monthly, can result in anemia.

Menstrual disorders

There is a wide spectrum of differences in how women experience menstruation. There are several ways that someone's menstrual cycle can differ from the norm, any of which should be discussed with a doctor to identify the underlying cause:

| Symptom | See article |

|---|---|

| Infrequent periods | Oligomenorrhea |

| Short or extremely light periods | Hypomenorrhea |

| Too-frequent periods (defined as more frequently than every 21 days) | Polymenorrhea |

| Extremely heavy or long periods (one guideline is soaking a sanitary napkin or tampon every hour or so, or menstruating for longer than 7 days) | Hypermenorrhea |

| Extremely painful periods | Dysmenorrhea |

| Breakthrough bleeding (also called spotting) between periods; normal in many females | Metrorrhagia |

| Absent periods | Amenorrhea |

There is a movement among gynecologists to discard the terms noted above, which although they are widely used, do not have precise definitions. Many now argue to describe menstruation in simple terminology, including:

- Cycle regularity (irregular, regular, or absent)

- Frequency of menstruation (frequent, normal, or infrequent)

- Duration of menstrual flow (prolonged, normal, or shortened)

- Volume of menstrual flow (heavy, normal, or light)[23]

Dysfunctional uterine bleeding is a hormonally caused bleeding abnormality. Dysfunctional uterine bleeding typically occurs in premenopausal women who do not ovulate normally (i.e. are anovulatory). All these bleeding abnormalities need medical attention; they may indicate hormone imbalances, uterine fibroids, or other problems. As pregnant women may bleed, a pregnancy test forms part of the evaluation of abnormal bleeding.

Women who had undergone female genital mutilation (particularly type III- infibulation) a practice common in parts of Africa, may experience menstrual problems, such as slow and painful menstruation, that is caused by the near-complete sealing off of the vagina.[24]

Premature or delayed menarche should be investigated if menarche begins before 9 years, if menarche has not begun by age 15, if there is no breast development by age 13, or if there is no period by 3 years after the onset of breast development.[5]

Ovulation suppression

Birth control

Since the late 1960s, many women have chosen to control the frequency of menstruation with hormonal birth control pills. They are most often combined hormone pills containing estrogen and are taken in 28 day cycles, 21 hormonal pills with either a 7-day break from pills, or 7 placebo pills during which the woman menstruates. Hormonal birth control acts by using low doses of hormones to prevent ovulation, and thus prevent pregnancy in sexually active women. But by using placebo pills for a 7-day span during the month, a regular bleeding period is still experienced.

Injections such as depo-provera became available in the 1960s. Progestogen implants such as Norplant in the 1980s and extended cycle combined oral contraceptive pills in the early 2000s.

Using synthetic hormones, it is possible for a woman to completely eliminate menstrual periods.[25] When using progestogen implants, menstruation may be reduced to 3 or 4 menstrual periods per year. By taking progestogen-only contraceptive pills (sometimes called the 'mini-pill') continuously without a 7-day span of using placebo pills, menstrual periods do not occur. Some women do this simply for convenience in the short-term,[26] while others prefer to eliminate periods altogether when possible.

Some women use hormonal contraception in this way to eliminate their periods for months or years at a time, a practice called menstrual suppression. When the first birth control pill was being developed, the researchers were aware that they could use the contraceptive to space menstrual periods up to 90 days apart, but they settled on a 28-day cycle that would mimic a natural menstrual cycle and produce monthly periods. The intention behind this decision was the hope of the inventor, John Rock, to win approval for his invention from the Roman Catholic Church. That attempt failed, but the 28-day cycle remained the standard when the pill became available to the public.[27] There is debate among medical researchers about the potential long-term impacts of these practices upon female health. Some researchers point to the fact that historically, females have had far fewer menstrual periods throughout their lifetimes, a result of shorter life expectancies, as well as a greater length of time spent pregnant or breast-feeding, which reduced the number of periods experienced by females.[28] These researchers believe that the higher number of menstrual periods by females in modern societies may have a negative impact upon their health. On the other hand, some researchers believe there is a greater potential for negative impacts from exposing females perhaps unnecessarily to regular low doses of synthetic hormones over their reproductive years.[29]

Breastfeeding

Breastfeeding causes negative feedback to occur on pulse secretion of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) and luteinizing hormone (LH). Depending on the strength of the negative feedback, breastfeeding women may experience complete suppression of follicular development, follicular development but no ovulation, or normal menstrual cycles may resume.[30] Suppression of ovulation is more likely when suckling occurs more frequently.[31] The production of prolactin in response to suckling is important to maintaining lactational amenorrhea.[32] On average, women who are fully breastfeeding whose infants suckle frequently experience a return of menstruation at fourteen and a half months postpartum. There is a wide range of response among individual breastfeeding women, however, with some experiencing return of menstruation at two months and others remaining amenorrheic for up to 42 months postpartum.[33]

Menstrual management

Menstruation is managed by menstruating women to avoid damage to clothing or to accord with norms of public life. Menstrual management practices range from medical suppression of menstruation, through wearing special garments or other items, washing or avoidance of washing, disposal and laundry of stained materials, to separation of menstruators to particular places or activities.

Menstrual products (also called "feminine hygiene" products) are made to absorb or catch menstrual blood. A number of different products are available - some are disposable, some are reusable. Where women can afford it, items used to absorb or catch menses are usually commercially manufactured products. In developing countries, many women may not afford these products and use materials found in the environment or other improvised materials.

Disposable items

- Sanitary napkins (Sanitary towels) or pads – Somewhat rectangular pieces of material worn in the underwear to absorb menstrual flow, often with "wings", pieces that fold around the undergarment and/or an adhesive backing to hold the pad in place. Disposable pads may contain wood pulp or gel products, usually with a plastic lining and bleached. Some sanitary napkins, particularly older styles, are held in place by a belt-like apparatus, instead of adhesive or wings.

- Tampons – Disposable cylinders of treated rayon/cotton blends or all-cotton fleece, usually bleached, that are inserted into the vagina to absorb menstrual flow.

- Padettes – Disposable wads of treated rayon/cotton blend fleece that are placed within the inner labia to absorb menstrual flow.

- Disposable menstrual cups – A firm, flexible cup-shaped device worn inside the vagina to catch menstrual flow. Disposable cups are made of soft plastic.

Reusable items

- Reusable cloth pads – Pads that are made of cotton (often organic), terrycloth, or flannel, and may be handsewn (from material or reused old clothes and towels) or storebought.

- Menstrual cups – A firm, flexible bell-shaped device worn inside the vagina for about half a day or overnight to catch menstrual flow. They are emptied into the toilet or sink when full, washed and re-inserted (washing hands with soap before doing so is crucial). Menstrual cups are usually made of silicone and can last 5 years or longer. At the end of the period, they are sterilised, usually by boiling in water.

- Sea sponges – Natural sponges, worn internally like a tampon to absorb menstrual flow.

- Padded panties – Reusable cloth (usually cotton) underwear with extra absorbent layers sewn in to absorb flow.

- Blanket, towel – (also known as a draw sheet) – large reusable piece of cloth, most often used at night, placed between legs to absorb menstrual flow.

Non-commercial materials

Absorption materials that may be used by women who cannot afford anything else include: sand, ash, small hole in earth,[34] cloth - new or re-used, whole leaf, leaf fibre (such as water hyacinth, banana, papyrus, cotton fibre), paper (toilet paper, re-used newspaper, pulped and dried paper),[35] animal pelt e.g. goat skin,[34] double layer of underwear, skirt or sari.[36]

Society and culture

Traditions and taboos

Many religions have menstruation-related traditions, for example the laws of Niddah in Judaism. These may ban certain actions during menstruation (such as sexual intercourse in some movements of Judaism and Islam), or rituals performed at the end of each menses (such as the mikvah in Judaism and the ghusl in Islam). Some traditional societies sequester women in residences called "menstrual huts" that are reserved for that exclusive purpose.

In Hinduism, it is also frowned upon to go to a temple and do pooja (i.e., pray) or do pooja at religious events if you are menstruating. Saraswati, the Hindu goddess of knowledge, is associated with menstruation; the literal translation of her name is "flow – woman". Metaformic Theory, as proposed by cultural theorist Judy Grahn and others, places menstruation as a central organizing idea in the creation of culture[citation needed] and the formation of humans' earliest rituals.

Although most Christian denominations do not follow any specific or prescribed rites for menstruation, the Western civilization, which has been predominantly Christian, has a history of menstrual taboos, with menstruating women having been believed to be dangerous.[37][38]

Anthropologists, Lock and Nguyen (2010), have noted that the heavy medicalization of the reproductive life-stages of women in the West, mimic power structures that are deemed, in other cultural practices, to function as a form of "social control".[39] Medicalization of the stages of women's lives, such as birth and menstruation, has enlivened a feminist perspective that investigates the social implications of biomedicine’s practice. "[C]ultural analysis of reproduction…attempts to show how women…exhibit resistance and create dominant alternative meanings about the body and reproduction to those dominant among the medical profession."[39]

In some parts of South Asia, women are isolated during menstruation. In 2005, in Nepal, the Supreme Court abolished the practice of keeping women in cow-sheds during menstruation.[40]

Sexual activity

Sexual intercourse during menstruation does not cause damage in and of itself, but the woman's body is more vulnerable during this time. Vaginal pH is higher and less acidic than normal,[41] the cervix is lower in its position, the cervical opening is more dilated, and the uterine endometrial lining is absent, thus allowing organisms direct access to the blood stream through the numerous blood vessels that nourish the uterus. All these conditions increase the chance of infection during menstruation.[citation needed]

Other aspects

Male menstruation is a term used colloquially for a type of bleeding in the urine or faeces of males, reported in some tropical countries. It is actually caused by parasite infestation of the urinary tract or intestines by Schistosoma haematobium, and cases of it are actually schistosomiasis, formerly known as bilharziasis.

Evolution

All female placental mammals have a uterine lining that builds up when the animal is fertile, but it is dismantled when the animal is infertile. Most female mammals have an estrous cycle, yet only primates (including humans), several species of bats, and elephant shrews have a menstrual cycle.[42] Some anthropologists have questioned the energy cost of rebuilding the endometrium every fertility cycle. However, anthropologist Beverly Strassmann has proposed that the energy savings of not having to continuously maintain the uterine lining more than offsets energy cost of having to rebuild the lining in the next fertility cycle, even in species such as humans where much of the lining is lost through bleeding (overt menstruation) rather than reabsorbed (covert menstruation).[43][44]

Many have questioned the evolution of overt menstruation in humans and related species, speculating on what advantage there could be to losing blood associated with dismantling the endometrium, rather than absorbing it, as most mammals do. Humans do, in fact, reabsorb about two-thirds of the endometrium each cycle. Strassmann asserts that overt menstruation occurs not because it is beneficial in itself. Rather, the fetal development of these species requires a more developed endometrium, one which is too thick to reabsorb completely. Strassman correlates species that have overt menstruation to those that have a large uterus relative to the adult female body size.[43]

Beginning in 1971, some research suggested that menstrual cycles of cohabiting human females became synchronized. A few anthropologists hypothesized that in hunter-gatherer societies, males would go on hunting journeys whilst the females of the tribe were menstruating, speculating that the females would not have been as receptive to sexual relations while menstruating.[45][46] However, there is currently significant dispute as to whether menstrual synchrony exists.[47]

See also

References

- ^ a b c Women's Gynecologic Health. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. 2011. p. 94. ISBN 9780763756376.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Menstruation and the menstrual cycle fact sheet". Office of Women's Health. 23 December 2014. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- ^ a b c Biggs, WS; Demuth, RH (15 October 2011). "Premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder". American family physician. 84 (8): 918–24. PMID 22010771.

- ^ a b c d "Premenstrual syndrome (PMS) fact sheet". Office on Women's Health. 23 December 2014. Retrieved 23 June 2015.

- ^ a b c d e American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on, Adolescence; American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Adolescent Health, Care; Diaz, A; Laufer, MR; Breech, LL (November 2006). "Menstruation in girls and adolescents: using the menstrual cycle as a vital sign". Pediatrics. 118 (5): 2245–50. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-2481. PMID 17079600.

- ^ a b "Menopause: Overview". http://www.nichd.nih.gov. 28 June 2013. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

{{cite web}}: External link in|website= - ^ Kristin H. Lopez (2013). Human Reproductive Biology. Academic Press. p. 53. ISBN 9780123821850.

- ^ Martin RD (2007). "The evolution of human reproduction: a primatological perspective". Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. Suppl 45: 59–84. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20734. PMID 18046752.

- ^ Karapanou, O.; Papadimitriou, A. (2010). "Determinants of menarche". Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 8: 115. doi:10.1186/1477-7827-8-115. PMID 20920296.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c Ziporyn, Karen J. Carlson, Stephanie A. Eisenstat, Terra (2004). The new Harvard guide to women's health. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01343-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Price WA, Giannini AJ (1983). "Binge eating during menstruation". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 44 (11): 431. PMID 6580290.

- ^ "Water retention: Relieve this premenstrual symptom". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 20 September 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Dysmenorrhea: Menstrual Abnormalities: Merck Manual Professional

- ^ Menstrual Reduction With Extended Use of Combination Oral Co... : Obstetrics & Gynecology

- ^ Marjoribanks, J; Proctor, M; Farquhar, C; Derks, RS (20 January 2010). "Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for dysmenorrhoea". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews (1): CD001751. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001751.pub2. PMID 20091521.

- ^ "Period makeovers: Fixes for heavy bleeding, cramps, PMS - CNN.com". CNN. 25 September 2007.

- ^ Medscape: Medscape Access

- ^ Sharma P, Malhotra C, Taneja DK, Saha R (2008). "Problems related to menstruation amongst adolescent girls". Indian J Pediatr. 75 (2): 125–9. doi:10.1007/s12098-008-0018-5. PMID 18334791.

- ^ Farage, Miranda (22 March 2013). The Vulva: Anatomy, Physiology, and Pathology. CRC Press. pp. 155–158.

- ^ "Menstrual blood problems: Clots, color and thickness". WebMD. Retrieved 20 September 2011.

- ^ Clancy, Kate (27 July 2011). "Iron-deficiency is not something you get just for being a lady". SciAm.

{{cite web}}: External link in|author= - ^ Kepczyk T, Cremins JE, Long BD, Bachinski MB, Smith LR, McNally PR (January 1999). "A prospective, multidisciplinary evaluation of premenopausal women with iron-deficiency anemia". Am. J. Gastroenterol. 94 (1): 109–15. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.00780.x. PMID 9934740.

- ^ Fraser IS, Critchley HO, Munro MG, Broder M (2007). "Can we achieve international agreement on terminologies and definitions used to describe abnormalities of menstrual bleeding?". Hum Reprod. 22 (3): 635–43. doi:10.1093/humrep/del478. PMID 17204526.

- ^ http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/fgm/health_consequences_fgm/en/

- ^ "Delaying your period with birth control pills". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 20 September 2011.

- ^ "How can I delay my period while on holiday?". National Health Service, United Kingdom. Retrieved 20 September 2011.

- ^ "Do you really need to have a period every month?". Discovery Health. Retrieved 20 September 2011.

- ^ Amy Lind; Stephanie Brzuzy (2007). Battleground: Women, Gender, and Sexuality: Volume 2: M–Z. Greenwood. p. 348. ISBN 978-0-313-34039-0.

- ^ Kam, Katherine. "Eliminate periods with birth control?". WebMD. Retrieved 20 September 2011.

- ^ McNeilly AS (2001). "Lactational control of reproduction". Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 13 (7–8): 583–90. doi:10.1071/RD01056. PMID 11999309.

- ^ Kippley, John; Sheila Kippley (1996). The Art of Natural Family Planning (4th ed.). Cincinnati, OH: The Couple to Couple League. p. 347. ISBN 0-926412-13-2.

- ^ Stallings JF, Worthman CM, Panter-Brick C, Coates RJ (February 1996). "Prolactin response to suckling and maintenance of postpartum amenorrhea among intensively breastfeeding Nepali women". Endocr. Res. 22 (1): 1–28. doi:10.3109/07435809609030495. PMID 8690004.

- ^ "Breastfeeding: Does It Really Space Babies?". The Couple to Couple League International. Internet Archive. 17 January 2008. Archived from the original on 17 January 2008. Retrieved 21 September 2008., which cites:

- Kippley SK, Kippley JF (November–December 1972). "The relation between breastfeeding and amenorrhea". Journal of obstetric, gynecologic, and neonatal nursing. 1 (4): 15–21. doi:10.1111/j.1552-6909.1972.tb00558.x. PMID 4485271.

- Sheila Kippley (November–December 1986 and January–February 1987). "Breastfeeding survey results similar to 1971 study". The CCL News. 13 (3): 10.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) and 13(4): 5.

- ^ a b Tamiru, S., Mamo, K., Acidria, P., Mushi, R., Satya Ali, C., Ndebele, L. (2015) Towards a sustainable solution for school menstrual hygiene management: cases of Ethiopia, Uganda, South-Sudan, Tanzania, and Zimbabwe. Waterlines, Vol. 34, No.1

- ^ House, S., Mahon, T., Cavill, S. (2012). Menstrual hygiene matters - A resource for improving menstrual hygiene around the world. WaterAid, UK

- ^ Chin, L. (2014) Period of shame - The Effects of Menstrual Hygiene Management on Rural Women and Girls' Quality of Life in Savannakhet, Laos [Master's thesis] LUMID International Master programme in applied International Development and Management http://lup.lub.lu.se/student-papers/record/4442938 [accessed 10 August 2015]

- ^ http://ispub.com/IJWH/5/2/8213

- ^ http://ebooks.adelaide.edu.au/f/frazer/james/golden/chapter60.html

- ^ a b Lock, M. & Nguyen, V.-K., 2010. An Anthropology of Biomedicine. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

- ^ Sushil Sharma, "Women hail menstruation ruling", BBC News, 15 September 2005.

- ^ Ann Intern Med. 1982 Jun; 96(6 Pt 2):921–3. "Vaginal physiology during menstruation."

- ^ "Why do women menstruate?". ScienceBlogs. 2011. Retrieved 15 January 2013.

- ^ a b Strassmann BI (1996). "The evolution of endometrial cycles and menstruation". The Quarterly Review of Biology. 71 (2): 181–220. doi:10.1086/419369. PMID 8693059.

- ^ Kathleen O'Grady (2000). "Is Menstruation Obsolete?". The Canadian Women's Health Network. Retrieved 21 January 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Desmond Morris (1997). "The Human Sexes". Cambridge University Press.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Chris Knight (1991). Blood relations: menstruation and the origins of culture. New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-06308-3.

- ^ Adams, Cecil (20 December 2002). "Does menstrual synchrony really exist?". The Straight Dope. The Chicago Reader. Retrieved 10 January 2007.

Further reading

- Howie, Gillian; Shail, Andrew (2005). Menstruation: A Cultural History. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 1-4039-3935-7. Retrieved 9 November 2013.

- Knight, Chris (1995). Blood Relations: Menstruation and the Origins of Culture. New Haven and London: Yale University. ISBN 0-300-04911-0. Retrieved 9 November 2013.

External links