American black duck: Difference between revisions

m →Taxonomy and etymology: Per consensus in discussion at Talk:New York#Proposed action to resolve incorrect incoming links using AWB |

Rescuing 1 sources and tagging 0 as dead. #IABot (v1.4) |

||

| Line 65: | Line 65: | ||

{{See also|Black Duck Joint Venture}} |

{{See also|Black Duck Joint Venture}} |

||

Since 1988, the american black duck has been rated of [[least concern]] on the [[IUCN Red List]] of Endangered species.<ref name=":1">{{Cite web|url=http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/22680174/0|title=Anas rubripes (American Black Duck, Black Duck)|website=www.iucnredlist.org|access-date=2017-06-29}}</ref> This is because the range of this species is extremely large, which is not near the threshold of [[Vulnerable species|vulnerable]] species.<ref name=":1" /> In addition, the population of the american black duck is much larger, and the population decline is also not as rapid to rate this species as vulnerable.<ref name=":1" /> The black duck has long been valued as a game bird, being extremely wary and fast on the wing.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.co.in/books?id=rjM3AQAAMAAJ&pg=PA167&dq|title=Lake Umbagog National Wildlife Refuge (N.W.R.), Conservation Plan: Environmental Impact Statement|date=2007|language=en}}</ref> Habitat loss due drainage and filling of wetlands due to urbanization, global warming, and the rise of sea level, is a major reason for the declining population of the american black duck.<ref name=":2">{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.co.in/books?id=NTqpIpyE5fUC&pg=PA57&dq|title=Birder's Conservation Handbook: 100 North American Birds at Risk|last=Wells|first=Jeffrey V.|date=2010-04-18|publisher=Princeton University Press|isbn=1400831512|language=en}}</ref> Some conservationists consider the hybridization and competition with the [[mallard]] an additional source of concern, should this decline continue.<ref name=rhymer>{{cite journal|last=Rhymer|first= |

Since 1988, the american black duck has been rated of [[least concern]] on the [[IUCN Red List]] of Endangered species.<ref name=":1">{{Cite web|url=http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/22680174/0|title=Anas rubripes (American Black Duck, Black Duck)|website=www.iucnredlist.org|access-date=2017-06-29}}</ref> This is because the range of this species is extremely large, which is not near the threshold of [[Vulnerable species|vulnerable]] species.<ref name=":1" /> In addition, the population of the american black duck is much larger, and the population decline is also not as rapid to rate this species as vulnerable.<ref name=":1" /> The black duck has long been valued as a game bird, being extremely wary and fast on the wing.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.co.in/books?id=rjM3AQAAMAAJ&pg=PA167&dq|title=Lake Umbagog National Wildlife Refuge (N.W.R.), Conservation Plan: Environmental Impact Statement|date=2007|language=en}}</ref> Habitat loss due drainage and filling of wetlands due to urbanization, global warming, and the rise of sea level, is a major reason for the declining population of the american black duck.<ref name=":2">{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.co.in/books?id=NTqpIpyE5fUC&pg=PA57&dq|title=Birder's Conservation Handbook: 100 North American Birds at Risk|last=Wells|first=Jeffrey V.|date=2010-04-18|publisher=Princeton University Press|isbn=1400831512|language=en}}</ref> Some conservationists consider the hybridization and competition with the [[mallard]] an additional source of concern, should this decline continue.<ref name=rhymer>{{cite journal|last=Rhymer |first=Judith M. |year=2006 |title=Extinction by hybridization and introgression in anatine ducks |journal=Acta Zoologica Sinica |volume=52 |issue=Supplement |pages=583–585 |url=http://www.actazool.org/downloadpdf.asp?id=5145 |format=PDF |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20131203045456/http://www.actazool.org/downloadpdf.asp?id=5145 |archivedate=2013-12-03 }}</ref><ref name=simber>{{cite journal|last=Rhymer|first= Judith M. |last2= Simberloff|first2=Daniel |year=1996|title= Extinction by hybridization and introgression|journal=[[Annual Reviews|Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst.]]|volume=27|pages= 83–109|doi=10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.27.1.83}}</ref> The hybridization itself is not the major problem; [[natural selection]] will see to it that the best-adapted individuals still have the most offspring.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.co.in/books?id=asIoCAAAQBAJ&pg=PT8&dq|title=Domestic Duck|last=Ashton|first=Mike|date=2014-11-30|publisher=Crowood|isbn=9781847979704|language=en}}</ref> However, the reduced viability of female hybrids will cause some broods to fail in the long run, due to the death of the offspring before reproducing themselves.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.co.in/books?id=HHzT7a8LzkgC|title=Speciation and Biogeography of Birds|last=Newton|first=Ian|date=2003-02-25|publisher=Academic Press|isbn=9780080924991|language=en}}</ref> While this is not a problem in the plentiful mallard, it might place an additional strain on the american black duck's population. Recent research conducted for the [[Delta Waterfowl Foundation]] suggests that hybrids are a result of [[forced copulation]]s, and not a normal pairing choice by black hens.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.americanhunter.org/articles/black-ducks-in-peril/|title=Black Ducks in Peril|date=2013-03-01|work=American Hunter|accessdate=2013-03-02}}</ref> |

||

The [[United States Fish and Wildlife Service|United States Fist and Wildlife Service]] has continued to purchase and manage the habitat in many areas supporting the migratory stopover, wintering, and breeding populations of the american black duck.<ref name=":2" /> In addition, the [[Montezuma National Wildlife Refuge]] has purchased and restored over 1,000 acres of wetlands, in order to provide the stopover habitat for over 10,000 american black ducks during fall migration.<ref name=":2" /> Also, the Atlantic Coast Joint Venture has been protecting the habitat of the american black duck, through habitat restoration and land acquisition projects, mostly within their wintering and breeding areas.<ref name=":2" /> In 2003, a [[Boreal Forest Conservation Framework]] was adopted by conservation organisations, industries, and [[First Nations]], to protect the canadian boreal forests, including the american black duck's eastern canadian breeding range, where a large number of american black ducks breed.<ref name=":2" /> |

The [[United States Fish and Wildlife Service|United States Fist and Wildlife Service]] has continued to purchase and manage the habitat in many areas supporting the migratory stopover, wintering, and breeding populations of the american black duck.<ref name=":2" /> In addition, the [[Montezuma National Wildlife Refuge]] has purchased and restored over 1,000 acres of wetlands, in order to provide the stopover habitat for over 10,000 american black ducks during fall migration.<ref name=":2" /> Also, the Atlantic Coast Joint Venture has been protecting the habitat of the american black duck, through habitat restoration and land acquisition projects, mostly within their wintering and breeding areas.<ref name=":2" /> In 2003, a [[Boreal Forest Conservation Framework]] was adopted by conservation organisations, industries, and [[First Nations]], to protect the canadian boreal forests, including the american black duck's eastern canadian breeding range, where a large number of american black ducks breed.<ref name=":2" /> |

||

Revision as of 21:55, 3 July 2017

| American black duck | |

|---|---|

| |

| American black duck in flight | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Subfamily: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | A. rubripes

|

| Binomial name | |

| Anas rubripes (Brewster, 1902)

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Anas obscura Gmelin, 1789 | |

The American black duck (Anas rubripes) is a large dabbling duck. The scientific name is derived from Latin. Anas means "duck", and rubripes comes from ruber "red" and pes, "foot".[2] American black ducks are similar to mallards in size, and resemble the female mallard in coloration, although the black duck's plumage is darker. It is native to eastern North America and has shown reduction in numbers and increasing hybridization with the more common mallard as that species has spread with man-made habitat changes.

They are usually found in coastal and freshwater wetlands, including brackish marshes, estuaries, beaver ponds, shallow lakes, and wooded swamps. Although, during winter, they usually inhabit riverine areas, flooded timber, and agricultural marshes. The american black duck is a partially migratory species, and mostly winter in the east-central United States, especially coastal areas; some remain year-round in the Great Lakes region. The female lays six to fourteen greenish buff colored eggs.

The american black duck is considered to be a species of least concern by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). This is because of the extremely large range of this species, compared to the threshold for vulnerable species. In addition, the population of the american black duck is much larger, and the population decline is also not as rapid to rate this species as vulnerable.[3]

Taxonomy and etymology

The american black duck was described by the American ornithologist William Brewter as Anas obscura rubripes, for "red-legged black duck".[4] This was in his landmark article An Undescribed form of the Black Duck (Anas obscura), in The Auk's 19th volume, in 1902, to present out the differences between the two kinds of black ducks found in New England: one being comparatively small, with brownish legs and olivaceous or dusky bill, and the other being comparatively larger, with a lighter skin tone and bright red legs and a clear yellow bill.[4] The larger of the two was described as Anas obscura by the German naturalist Johann Friedrich Gmelin in 1789,[3] in the 13th edition of the Systema Naturae part 2, who based it on the "Ducky Duck" of Welsh naturalist Thomas Pennant.[4]

Pennant, in Arctic Zoology's volume 2, described it as coming "from the province of New York" and having "a long and narrow dusky bill, tinged with blue: chin white: neck pale brown, streaked downwards with dusky lines".[4] In a typical obscura, the characteristics such as greenish black, olive green, or dusky olive bill; olivaceous brown legs with at most one reddish tinge; the nape and pileum nearly uniformly dark; spotless chin and throat; fine linear and dusky markings on the neck and sides of the head, rather than blackish, do not vary with age or season.[4]

Description

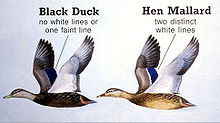

American black ducks weigh 720–1,640 g (1.59–3.62 lb), measure 54–59 cm (21–23 in) in length and 88–95 cm (35–37 in) across the wings.[5] Although they are similar to mallards in size and broadly overlap in weight, according to a manual of avian body masses, they have the highest mean body mass in the Anas genus, with 376 males averaging 1.4 kg (3.1 lb) and 176 females averaging 1.1 kg (2.4 lb).[6][7] The american black duck somewhat resembles the female mallard in coloration, although the black duck's plumage is darker.[8] The male and female black duck are generally similar in appearance, but the male's bill is yellow while the female's is a dull green, which may be flecked with black.[9][10] Also, there are dark marks on the upper mandible.[11] The head is slightly lighter brown than the dark brown body, with dark eyes, and has brown streaks on the cheek and throat and a dark streak going through the eye and crown.[8] The speculums are iridescent violet-blue with predominantly black margins.[11] The black duck has fleshy orange feet with dark web.[12] In flight, the white underwings lining can be seen in contrast to the dark brown body.[8] The behaviour and voice are the same as for the mallard drake.[13]

Distribution and habitat

The american black duck is endemic to eastern North America.[14] The range extends from northeastern Saskatchewan to Newfoundland and Labrador, in Canada.[8] In the United States, it is found in northern Illinois, Michigan, New Jersey, Ohio, Connecticut, Vermont, southern to northern South Dakota, central West Virginia, Maine, and on the Atlantic coast to North Carolina.[15][8]

The american black duck usually prefers freshwater and coastal wetlands throughout northeastern America, including brackish marshes and estuaries, and edges of backwater ponds and rivers, lined by speckled alder.[15][8] They also inhabit beaver ponds, shallow lakes with sedges and reeds, bogs in open boreal and mixed hardwood forests, and forested swamps.[15] The american black duck population of Vermont have found in glacial kettle ponds surrounded by bog mats.[15] During winter, the american black duck mostly inhabits brackish marshes bordering bays, agricultural marshes, flooded timber, agricultural fields, estuaries, and riverine areas.[15] They usually take shelter from hunting and other disturbances, by moving to brackish and fresh impoundments on conservation land.[5]

Behavior

Feeding

The american black duck is habitat generalist species and has a diverse diet.[16] They are omnivores, and feed on plant and animal matter.[17] These birds feed by dabbling in shallow water, and grazing on land.[17] Their plant diet primarily includes a wide variety of wetland grasses and sedges, seeds, stems, leaves, and roots-stalks of aquatic plants,[18] while their animal diet includes mollusks, snails, amphipods, insects, mussels, and small fishes.[17][16] They also forage on aquatic plants, such as eelgrass, pondweed, and smartweed.[19] During nesting, proportion of invertebrates increases.[18] During their breeding season, the american black ducks consume about 80% plant food and 20% animal food, which increases to 85% during winter.[17] Ducklings mostly eat water invertebrates for the first 12 days after hatching, including aquatic snowbugs, snails, mayflies, dragonflies, beetles, flies, caddisfly larvae.[17] After this, they shift to seeds and other plant food.[17]

Breeding

Their breeding habitat is alkaline marshes, acid bogs, lakes, ponds, rivers, marshes, brackish marshes, and the margins of estuaries and other aquatic environments in northern Saskatchewan, Manitoba, across Ontario and Quebec as well as the Atlantic Canadian Provinces, including the Great Lakes, and the Adirondacks in the United States.[20] This species is partially migratory and many winter in the east-central United States, especially coastal areas; some remain year-round in the Great Lakes region.[21]

American black ducks interbreed regularly and extensively with mallard ducks, to which they are closely related.[22] Some authorities even consider the black duck to be a subspecies of the mallard, instead of a separate species. Mank et al. argue that this is in error as the extent of hybridization alone is not a valid means to delimitate Anas species.[23]

In the past, it has been proposed that american black ducks and mallards were formerly separated by habitat preference, with the american black ducks’ dark plumage giving them a selective advantage in shaded forest pools in eastern North America, and the mallards’ lighter plumage giving an advantage in the brighter, more open prairie and plains lakes.[24] In recent times, according to this view, deforestation in the east, and tree planting on the plains, has broken down this habitat separation, leading to the high levels of hybridization now observed.[25] However, rates of past hybridization are unknown in this and most other avian hybrid zones, and it is merely presumed in the case of the american black duck that past hybridization rates were lower than those seen today. Also, many avian hybrid zones are known to be stable and longstanding despite the occurrence of extensive interbreeding.[22] American black ducks and local mallards are now very hard to distinguish by means of microsatellite comparisons, even if many specimens are sampled [26] Contrary to this study's claims, the question whether the american haplotypes are an original mallard lineage is far from resolved. Their statement, "[N]orthern black ducks are now no more distinct from mallards than their southern conspecifics" only holds true in regard to the molecular markers tested.[23] As birds indistinguishable according to the set of microsatellite markers still can look different, there are other genetic differences that were simply not tested in the study.[23]

It has been revealed in captivity studies, that most of the hybrids do not follow Haldane's Rule, but sometimes hybrid females die before they reach sexual maturity this underscores the case for the american black duck being a distinct species.[22][27] This duck is a rare vagrant to Great Britain and Ireland, where, over the years, several birds have settled in and bred with the local mallards.[28] The resulting hybrids can present considerable identification difficulties.[28]

Egg clutches number seven to eight oval eggs, which have smooth shells, and come in varied shades of white, cream white, and buff-green color.[29][20] A female american black duck lays six to fourteen eggs on average, with 30 days to hatching.[12] On an average, they measure 59.4 mm (2.34 in) long and 43.2 mm (1.70 in) wide, and weigh 56.6 g (0.125 lb).[20] The incubation period is of varied lengths,[20] but usually takes 25 to 26 days, with both sexes sharing duties, although the male usually defends the territory until the female reaches the middle of her incubation period.[29] It takes about 6 weeks to fledge.[29] Nest sites are well-concealed on the ground, often on uplands.[29] Once the egg hatches, the hen leads the broods to rearing areas with abundant invertebrates and vegetation.[29]

Nest predators and hazards

The apex nest predators of the american black duck include american crows, gulls, and racoons, especially in tree nests.[17] The great horned owl is also a major predator the adult species. Bullfrogs and snapping turtles are know to take away many ducklings.[17] Ducklings often catch diseases caused by protozoan blood parasites, which transmits by bites of insects such as the blackfly.[17] They are also vulnerable to lead shot poisoning, known as plumbism, due to their bottom-forage food habits.[17]

Status and conservation

Since 1988, the american black duck has been rated of least concern on the IUCN Red List of Endangered species.[3] This is because the range of this species is extremely large, which is not near the threshold of vulnerable species.[3] In addition, the population of the american black duck is much larger, and the population decline is also not as rapid to rate this species as vulnerable.[3] The black duck has long been valued as a game bird, being extremely wary and fast on the wing.[30] Habitat loss due drainage and filling of wetlands due to urbanization, global warming, and the rise of sea level, is a major reason for the declining population of the american black duck.[14] Some conservationists consider the hybridization and competition with the mallard an additional source of concern, should this decline continue.[31][32] The hybridization itself is not the major problem; natural selection will see to it that the best-adapted individuals still have the most offspring.[33] However, the reduced viability of female hybrids will cause some broods to fail in the long run, due to the death of the offspring before reproducing themselves.[34] While this is not a problem in the plentiful mallard, it might place an additional strain on the american black duck's population. Recent research conducted for the Delta Waterfowl Foundation suggests that hybrids are a result of forced copulations, and not a normal pairing choice by black hens.[35]

The United States Fist and Wildlife Service has continued to purchase and manage the habitat in many areas supporting the migratory stopover, wintering, and breeding populations of the american black duck.[14] In addition, the Montezuma National Wildlife Refuge has purchased and restored over 1,000 acres of wetlands, in order to provide the stopover habitat for over 10,000 american black ducks during fall migration.[14] Also, the Atlantic Coast Joint Venture has been protecting the habitat of the american black duck, through habitat restoration and land acquisition projects, mostly within their wintering and breeding areas.[14] In 2003, a Boreal Forest Conservation Framework was adopted by conservation organisations, industries, and First Nations, to protect the canadian boreal forests, including the american black duck's eastern canadian breeding range, where a large number of american black ducks breed.[14]

References

- ^ Template:IUCN

- ^ Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 46, 340. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ^ a b c d e "Anas rubripes (American Black Duck, Black Duck)". www.iucnredlist.org. Retrieved 2017-06-29.

- ^ a b c d e Union., American Ornithologists' (1902). "The Auk". v. 19 1902. ISSN 0004-8038.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "American Black Duck". www.allaboutbirds.org. 2011. Archived from the original on 2017-02-17. Retrieved 2017-06-29.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ CRC Handbook of Avian Body Masses by John B. Dunning Jr. (Editor). CRC Press (1992), ISBN 978-0-8493-4258-5.

- ^ CRC Handbook of Avian Body Masses, 2nd Edition by John B. Dunning Jr. (Editor). CRC Press (2008), ISBN 978-1-4200-6444-5.

- ^ a b c d e f Smith, Christopher (2000). Field Guide to Upland Birds and Waterfowl. Wilderness Adventures Press. ISBN 9781885106209.

- ^ Potter, Eloise F.; Parnell, James F.; Teulings, Robert P.; Davis, Ricky (2015-12-01). Birds of the Carolinas. UNC Press Books. ISBN 9781469625652.

- ^ Dunn, Jon Lloyd; Alderfer, Jonathan K. (2006). National Geographic Field Guide to the Birds of North America. National Geographic Books. ISBN 9780792253143.

- ^ a b Kear, Janet (2005). Ducks, Geese and Swans: Species accounts (Cairina to Mergus). Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198610090.

- ^ a b Ryan, James M. (April 2009). Adirondack Wildlife: A Field Guide. UPNE. ISBN 9781584657491.

- ^ "American Black Duck Facts and Figure". Ducks Unlimited. Archived from the original on 2016-03-25. Retrieved 2017-06-30.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ a b c d e f Wells, Jeffrey V. (2010-04-18). Birder's Conservation Handbook: 100 North American Birds at Risk. Princeton University Press. ISBN 1400831512.

- ^ a b c d e Cape Cod National Seashore (N.S.), Hunting Program: Environmental Impact Statement. 2007.

- ^ a b Maehr, David S.; II, Herbert W. Kale (2005). Florida's Birds: A Field Guide and Reference. Pineapple Press Inc. ISBN 9781561643356.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Eastman, John Andrew (1999). Birds of Lake, Pond, and Marsh: Water and Wetland Birds of Eastern North America. Stackpole Books. ISBN 9780811726818.

- ^ a b Kear, Janet (2005). Ducks, Geese and Swans: Species accounts (Cairina to Mergus). Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198610090.

- ^ Smith, Christopher (2000). Field Guide to Upland Birds and Waterfowl. Wilderness Adventures Press. ISBN 9781885106209.

- ^ a b c d Baldassarre, Guy A. (2014). Ducks, Geese, and Swans of North America. JHU Press. ISBN 9781421407517.

- ^ Jerry R., Longcore; McAuley, Daniel G.; Hepp, Gary R.; Rhymer, Judith M. (2000-01-01). "American Black Duck: Anas rubripes". Archived from the original on 2016-03-25. Retrieved 2017-06-30.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ a b c McCarthy, Eugene M. (2006). "Handbook of Avian Hybrids of the World". Oxford University Press.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c Mank, Judith E.; Carlson, John E.; Brittingham, Margaret C. (2004). "A century of hybridization: Decreasing genetic distance between American black ducks and mallards". Conservation Genetics. 5 (3): 395–403. doi:10.1023/B:COGE.0000031139.55389.b1.

- ^ Armistead, George L.; Sullivan, Brian L. (2015-12-08). Better Birding: Tips, Tools, and Concepts for the Field. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691129662.

- ^ Johnsgard, Paul A. (1967). "Sympatry Changes and Hybridization Incidence in Mallards and Black Ducks". American Midland Naturalist. 77 (1): 51–63. doi:10.2307/2423425.

- ^ Avise, John C.; Ankney, C. Davison; Nelson, William S. (1990). "Mitochondrial Gene Trees and the Evolutionary Relationship of Mallard and Black Ducks". Evolution. 44 (4): 1109–1119. doi:10.2307/2409570.

- ^ Kirby, Ronald E.; Sargeant, Glen A.; Shutler, Dave (2004). "Haldane's rule and American black duck × mallard hybridization". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 82 (11): 1827–1831. doi:10.1139/z04-169.

- ^ a b Evans, Lee G. R. (1994). Rare Birds in Britain 1800-1990. LGRE Productions Incorporated. ISBN 9781898918004.

- ^ a b c d e Schwartz, Nancy A. (2010-08-12). Wildlife Rehabilitation: Basic Life Support. Xlibris Corporation. ISBN 9781453531921.

- ^ Lake Umbagog National Wildlife Refuge (N.W.R.), Conservation Plan: Environmental Impact Statement. 2007.

- ^ Rhymer, Judith M. (2006). "Extinction by hybridization and introgression in anatine ducks". Acta Zoologica Sinica. 52 (Supplement): 583–585. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-12-03.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Rhymer, Judith M.; Simberloff, Daniel (1996). "Extinction by hybridization and introgression". Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 27: 83–109. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.27.1.83.

- ^ Ashton, Mike (2014-11-30). Domestic Duck. Crowood. ISBN 9781847979704.

- ^ Newton, Ian (2003-02-25). Speciation and Biogeography of Birds. Academic Press. ISBN 9780080924991.

- ^ "Black Ducks in Peril". American Hunter. 2013-03-01. Retrieved 2013-03-02.

External links

- American Black Duck Species Account – Cornell Lab of Ornithology

- "American Black Duck media". Internet Bird Collection.

- American Black Duck photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)

- Interactive range map of Anas rubripes at IUCN Red List maps