Visitor pattern: Difference between revisions

m Moved class diagrams to Structure section. |

Because this pattern was first described in Smalltalk, this edit adds an Smalltalk example. |

||

| Line 265: | Line 265: | ||

} |

} |

||

} |

} |

||

</syntaxhighlight> |

|||

== Smalltalk example == |

|||

<!-- There must be an Smalltalk example because it was Dan Ingalls who first described double dispatch in Smalltalk: |

|||

Daniel H. H. Ingalls. A Simple Technique for Handling Multiple Polymorphism. In Proceedings of OOPSLA '86, Object–Oriented Programming Systems, Languages and Applications, pages 347–349, November 1986. Printed as SIGPLAN Notices, 21(11). |

|||

--> |

|||

In this case, it is the object's responsibility to know how to print itself on a stream. |

|||

<syntaxhighlight lang="smalltalk"> |

|||

Object subclass: #Expression |

|||

instanceVariableNames: '' |

|||

classVariableNames: '' |

|||

package: 'Wikipedia'. |

|||

Expression subclass: #Literal |

|||

instanceVariableNames: 'value' |

|||

classVariableNames: '' |

|||

package: 'Wikipedia'. |

|||

Literal class>>with: aValue |

|||

^ self new |

|||

value: aValue; |

|||

yourself. |

|||

Literal>>value: aValue |

|||

value := aValue |

|||

Literal>>printOn: aStream |

|||

aStream nextPutAll: value asString |

|||

Expression subclass: #Addition |

|||

instanceVariableNames: 'left right' |

|||

classVariableNames: '' |

|||

package: 'Wikipedia' |

|||

Addition class>>left: a right: b |

|||

^ self new |

|||

left: a; |

|||

right: b; |

|||

yourself |

|||

Addition>>left: anExpression |

|||

left := anExpression |

|||

Addition>>right: anExpression |

|||

right := anExpression |

|||

Addition>>printOn: aStream |

|||

aStream nextPut: $(. |

|||

left printOn: aStream. |

|||

aStream nextPut: $+. |

|||

right printOn: aStream. |

|||

aStream nextPut: $) |

|||

WriteStream subclass: #ExpressionPrinter |

|||

instanceVariableNames: '' |

|||

classVariableNames: '' |

|||

package: 'Wikipedia' |

|||

Object subclass: #Program |

|||

instanceVariableNames: '' |

|||

classVariableNames: '' |

|||

package: 'Wikipedia' |

|||

Program>>main |

|||

| expression | |

|||

expression := Addition |

|||

left: (Addition |

|||

left: (Literal with: 1) |

|||

right: (Literal with: 2)) |

|||

right: (Literal with: 3). |

|||

expression printOn: Transcript. |

|||

Transcript flush |

|||

</syntaxhighlight> |

</syntaxhighlight> |

||

Revision as of 04:49, 19 November 2017

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2014) |

In object-oriented programming and software engineering, the visitor design pattern is a way of separating an algorithm from an object structure on which it operates. A practical result of this separation is the ability to add new operations to existent object structures without modifying the structures. It is one way to follow the open/closed principle.

In essence, the visitor allows adding new virtual functions to a family of classes, without modifying the classes. Instead, a visitor class is created that implements all of the appropriate specializations of the virtual function. The visitor takes the instance reference as input, and implements the goal through double dispatch.

Overview

The Visitor [1] design pattern is one of the twenty-three well-known GoF design patterns that describe how to solve recurring design problems to design flexible and reusable object-oriented software, that is, objects that are easier to implement, change, test, and reuse.

What problems can the Visitor design pattern solve? [2]

- It should be possible to define a new operation for (some) classes of an object structure without changing the classes.

When new operations are needed frequently and the object structure consists of many unrelated classes, it's inflexible to add new subclasses each time a new operation is required because "[..] distributing all these operations across the various node classes leads to a system that's hard to understand, maintain, and change." [1]

What solution does the Visitor design pattern describe?

- Define a separate (visitor) object that implements an operation to be performed on elements of an object structure.

- Clients traverse the object structure and call a dispatching operation accept(visitor) on an element — that "dispatches" (delegates) the request to the "accepted visitor object". The visitor object then performs the operation on the element ("visits the element").

This makes it possible to create new operations independently from the classes of an object structure by adding new visitor objects.

See also the UML class and sequence diagram below.

Definition

The Gang of Four defines the Visitor as:

Represent an operation to be performed on elements of an object structure. Visitor lets you define a new operation without changing the classes of the elements on which it operates.

The nature of the Visitor makes it an ideal pattern to plug into public APIs thus allowing its clients to perform operations on a class using a "visiting" class without having to modify the source.[3]

Uses

Moving operations into visitor classes is beneficial when

- many unrelated operations on an object structure are required,

- the classes that make up the object structure are known and not expected to change,

- new operations need to be added frequently,

- an algorithm involves several classes of the object structure, but it is desired to manage it in one single location,

- an algorithm needs to work across several independent class hierarchies.

A drawback to this pattern, however, is that it makes extensions to the class hierarchy more difficult, as new classes typically require a new visit method to be added to each visitor.

Use Case Example

Consider the design of a 2D computer-aided design (CAD) system. At its core there are several types to represent basic geometric shapes like circles, lines, and arcs. The entities are ordered into layers, and at the top of the type hierarchy is the drawing, which is simply a list of layers, plus some added properties.

A fundamental operation on this type hierarchy is saving a drawing to the system's native file format. At first glance it may seem acceptable to add local save methods to all types in the hierarchy. But it is also useful to be able to save drawings to other file formats. Adding ever more methods for saving into many different file formats soon clutters the relatively pure original geometric data structure.

A naive way to solve this would be to maintain separate functions for each file format. Such a save function would take a drawing as input, traverse it, and encode into that specific file format. As this is done for each added different format, duplication between the functions accumulates. For example, saving a circle shape in a raster format requires very similar code no matter what specific raster form is used, and is different from other primitive shapes. The case for other primitive shapes like lines and polygons is similar. Thus, the code becomes a large outer loop traversing through the objects, with a large decision tree inside the loop querying the type of the object. Another problem with this approach is that it is very easy to miss a shape in one or more savers, or a new primitive shape is introduced, but the save routine is implemented only for one file type and not others, leading to code extension and maintenance problems.

Instead, the Visitor pattern can be applied. It encodes a logical operation on the whole hierarchy into one class containing one method per type. In the CAD example, each save function would be implemented as a separate Visitor subclass. This would remove all duplication of type checks and traversal steps. It would also make the compiler complain if a shape is omitted.

Another motive is to reuse iteration code. For example, iterating over a directory structure could be implemented with a visitor pattern. This would allow creating file searches, file backups, directory removal, etc., by implementing a visitor for each function while reusing the iteration code.

Structure

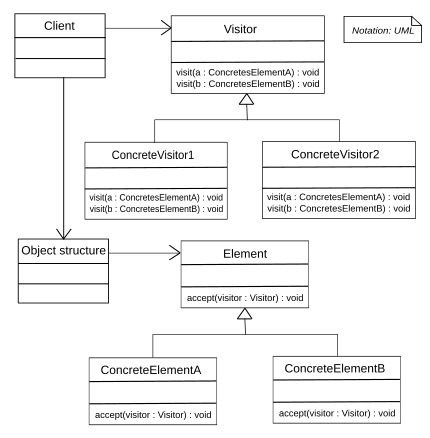

UML class and sequence diagram

In the above UML class diagram, the ElementA class doesn't implement a new operation directly.

Instead, ElementA implements a dispatching operation accept(visitor) that "dispatches" (delegates) a request to the "accepted visitor object" (visitor.visitElementA(this)). The Visitor1 class implements the operation (visitElementA(e:Element)).

ElementB then implements accept(visitor) by dispatching to visitor.visitElementB(this). The Visitor1 class implements the operation (visitElementB(e:Element)).

The UML sequence diagram

shows the run-time interactions: The Client object traverses the elements of an object structure (ElementA,ElementB) and calls accept(visitor) on each element.

First, the Client calls accept(visitor) on

ElementA, which calls visitElementA(this) on the accepted visitor object.

The element itself (this) is passed to the visitor so that

it can "visit" ElementA (call operationA()).

Thereafter, the Client calls accept(visitor) on

ElementB, which calls visitElementB(this) on the visitor that "visits" ElementB (calls operationB()).

Class diagram

Details

The visitor pattern requires a programming language that supports single dispatch, as common object-oriented languages (such as C++, Java, Smalltalk, Objective-C, Swift, JavaScript, and Python) do. Under this condition, consider two objects, each of some class type; one is termed the element, and the other is visitor.

The visitor declares a visit method, which takes the element as an argument, for each class of element. Concrete visitors are derived from the visitor class and implement these visit methods, each of which implements part of the algorithm operating on the object structure. The state of the algorithm is maintained locally by the concrete visitor class.

The element declares an accept method to accept a visitor, taking the visitor as an argument. Concrete elements, derived from the element class, implement the accept method. In its simplest form, this is no more than a call to the visitor’s visit method. Composite elements, which maintain a list of child objects, typically iterate over these, calling each child’s accept method.

The client creates the object structure, directly or indirectly, and instantiates the concrete visitors. When an operation is to be performed which is implemented using the Visitor pattern, it calls the accept method of the top-level element(s).

When the accept method is called in the program, its implementation is chosen based on both the dynamic type of the element and the static type of the visitor. When the associated visit method is called, its implementation is chosen based on both the dynamic type of the visitor and the static type of the element, as known from within the implementation of the accept method, which is the same as the dynamic type of the element. (As a bonus, if the visitor can't handle an argument of the given element's type, then the compiler will catch the error.)

Thus, the implementation of the visit method is chosen based on both the dynamic type of the element and the dynamic type of the visitor. This effectively implements double dispatch. For languages whose object systems support multiple dispatch, not only single dispatch, such as Common Lisp or C# via the Dynamic Language Runtime (DLR), implementation of the visitor pattern is greatly simplified (a.k.a. Dynamic Visitor) by allowing use of simple function overloading to cover all the cases being visited. A dynamic visitor, provided it operates on public data only, conforms to the open/closed principle (since it does not modify extant structures) and to the single responsibility principle (since it implements the Visitor pattern in a separate component).

In this way, one algorithm can be written to traverse a graph of elements, and many different kinds of operations can be performed during that traversal by supplying different kinds of visitors to interact with the elements based on the dynamic types of both the elements and the visitors.

C# example

This example shows how to print a tree representing a numeric expression involving literals and their addition. The same example is presented using both classic and Dynamic Language Runtime implementations.

Classic visitor

A classic visitor where the Print operations for each type are implemented in one ExpressionPrinter class as a number of overloads of the Visit method.

namespace Wikipedia

{

using System;

using System.Text;

interface IExpressionVisitor

{

void Visit(Literal literal);

void Visit(Addition addition);

}

interface IExpression

{

void Accept(IExpressionVisitor visitor);

}

class Literal : IExpression

{

internal double Value { get; set; }

public Literal(double value)

{

this.Value = value;

}

public void Accept(IExpressionVisitor visitor)

{

visitor.Visit(this);

}

}

class Addition : IExpression

{

internal IExpression Left { get; set; }

internal IExpression Right { get; set; }

public Addition(IExpression left, IExpression right)

{

this.Left = left;

this.Right = right;

}

public void Accept(IExpressionVisitor visitor)

{

visitor.Visit(this);

}

}

class ExpressionPrinter : IExpressionVisitor

{

StringBuilder sb;

public ExpressionPrinter(StringBuilder sb)

{

this.sb = sb;

}

public void Visit(Literal literal)

{

sb.Append(literal.Value);

}

public void Visit(Addition addition)

{

sb.Append("(");

addition.Left.Accept(this);

sb.Append("+");

addition.Right.Accept(this);

sb.Append(")");

}

}

public class Program

{

public static void Main(string[] args)

{

// emulate 1+2+3

var e = new Addition(

new Addition(

new Literal(1),

new Literal(2)

),

new Literal(3)

);

var sb = new StringBuilder();

var expressionPrinter = new ExpressionPrinter(sb);

e.Accept(expressionPrinter);

Console.WriteLine(sb);

}

}

}

Dynamic Visitor

This example declares a separate ExpressionPrinter class that takes care of the printing. Note that the expression classes have to expose their members to make this possible.

namespace Wikipedia

{

using System;

using System.Text;

abstract class Expression

{

}

class Literal : Expression

{

public double Value { get; }

public Literal(double value)

{

this.Value = value;

}

}

class Addition : Expression

{

public Expression Left { get; }

public Expression Right { get; }

public Addition(Expression left, Expression right)

{

Left = left;

Right = right;

}

}

class ExpressionPrinter

{

public static void Print(Literal literal, StringBuilder sb)

{

sb.Append(literal.Value);

}

public static void Print(Addition addition, StringBuilder sb)

{

sb.Append("(");

Print((dynamic) addition.Left, sb);

sb.Append("+");

Print((dynamic) addition.Right, sb);

sb.Append(")");

}

}

class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

// emulate 1+2+3

var e = new Addition(

new Addition(

new Literal(1),

new Literal(2)

),

new Literal(3)

);

var sb = new StringBuilder();

ExpressionPrinter.Print((dynamic) e, sb);

Console.WriteLine(sb);

}

}

}

Smalltalk example

In this case, it is the object's responsibility to know how to print itself on a stream.

Object subclass: #Expression

instanceVariableNames: ''

classVariableNames: ''

package: 'Wikipedia'.

Expression subclass: #Literal

instanceVariableNames: 'value'

classVariableNames: ''

package: 'Wikipedia'.

Literal class>>with: aValue

^ self new

value: aValue;

yourself.

Literal>>value: aValue

value := aValue

Literal>>printOn: aStream

aStream nextPutAll: value asString

Expression subclass: #Addition

instanceVariableNames: 'left right'

classVariableNames: ''

package: 'Wikipedia'

Addition class>>left: a right: b

^ self new

left: a;

right: b;

yourself

Addition>>left: anExpression

left := anExpression

Addition>>right: anExpression

right := anExpression

Addition>>printOn: aStream

aStream nextPut: $(.

left printOn: aStream.

aStream nextPut: $+.

right printOn: aStream.

aStream nextPut: $)

WriteStream subclass: #ExpressionPrinter

instanceVariableNames: ''

classVariableNames: ''

package: 'Wikipedia'

Object subclass: #Program

instanceVariableNames: ''

classVariableNames: ''

package: 'Wikipedia'

Program>>main

| expression |

expression := Addition

left: (Addition

left: (Literal with: 1)

right: (Literal with: 2))

right: (Literal with: 3).

expression printOn: Transcript.

Transcript flush

C++ example

Sources

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

class AbstractDispatcher; // Forward declare AbstractDispatcher

class File { // Parent class for the elements (ArchivedFile, SplitFile and ExtractedFile)

public:

// This function accepts an object of any class derived from AbstractDispatcher and must be implemented in all derived classes

virtual void accept(AbstractDispatcher &dispatcher) = 0;

};

// Forward declare specific elements (files) to be dispatched

class ArchivedFile;

class SplitFile;

class ExtractedFile;

class AbstractDispatcher { // Declares the interface for the dispatcher

public:

// Declare overloads for each kind of a file to dispatch

virtual void dispatch(ArchivedFile &file) = 0;

virtual void dispatch(SplitFile &file) = 0;

virtual void dispatch(ExtractedFile &file) = 0;

};

class ArchivedFile: public File { // Specific element class #1

public:

// Resolved at runtime, it calls the dispatcher's overloaded function, corresponding to ArchivedFile.

void accept(AbstractDispatcher &dispatcher) override {

dispatcher.dispatch(*this);

}

};

class SplitFile: public File { // Specific element class #2

public:

// Resolved at runtime, it calls the dispatcher's overloaded function, corresponding to SplitFile.

void accept(AbstractDispatcher &dispatcher) override {

dispatcher.dispatch(*this);

}

};

class ExtractedFile: public File { // Specific element class #3

public:

// Resolved at runtime, it calls the dispatcher's overloaded function, corresponding to ExtractedFile.

void accept(AbstractDispatcher &dispatcher) override {

dispatcher.dispatch(*this);

}

};

class Dispatcher: public AbstractDispatcher { // Implements dispatching of all kind of elements (files)

public:

void dispatch(ArchivedFile &file) override {

std::cout << "dispatching ArchivedFile" << std::endl;

}

void dispatch(SplitFile &file) override {

std::cout << "dispatching SplitFile" << std::endl;

}

void dispatch(ExtractedFile &file) override {

std::cout << "dispatching ExtractedFile" << std::endl;

}

};

int main() {

ArchivedFile archivedFile;

SplitFile splitFile;

ExtractedFile extractedFile;

std::vector<File*> files;

files.push_back(&archivedFile);

files.push_back(&splitFile);

files.push_back(&extractedFile);

Dispatcher dispatcher;

for (File* file : files) {

file->accept(dispatcher);

}

}

Output

dispatching ArchivedFile dispatching SplitFile dispatching ExtractedFile

Java example

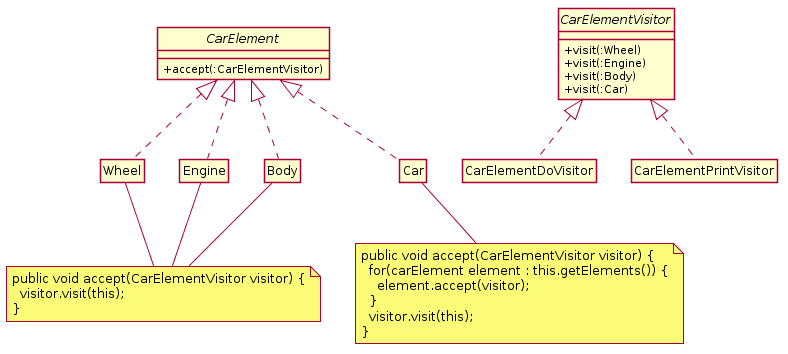

The following example is in the language Java, and shows how the contents of a tree of nodes (in this case describing the components of a car) can be printed. Instead of creating print methods for each node subclass (Wheel, Engine, Body, and Car), one visitor class (CarElementPrintVisitor) performs the required printing action. Because different node subclasses require slightly different actions to print properly, CarElementPrintVisitor dispatches actions based on the class of the argument passed to its visit method. CarElementDoVisitor, which is analogous to a save operation for a different file format, does likewise.

Diagram

Sources

interface CarElement {

void accept(CarElementVisitor visitor);

}

interface CarElementVisitor {

void visit(Body body);

void visit(Car car);

void visit(Engine engine);

void visit(Wheel wheel);

}

class Car implements CarElement {

CarElement[] elements;

public Car() {

this.elements = new CarElement[] {

new Wheel("front left"), new Wheel("front right"),

new Wheel("back left"), new Wheel("back right"),

new Body(), new Engine()

};

}

public void accept(final CarElementVisitor visitor) {

for (CarElement elem : elements) {

elem.accept(visitor);

}

visitor.visit(this);

}

}

class Body implements CarElement {

public void accept(final CarElementVisitor visitor) {

visitor.visit(this);

}

}

class Engine implements CarElement {

public void accept(final CarElementVisitor visitor) {

visitor.visit(this);

}

}

class Wheel implements CarElement {

private String name;

public Wheel(final String name) {

this.name = name;

}

public String getName() {

return name;

}

public void accept(final CarElementVisitor visitor) {

/*

* accept(CarElementVisitor) in Wheel implements

* accept(CarElementVisitor) in CarElement, so the call

* to accept is bound at run time. This can be considered

* the *first* dispatch. However, the decision to call

* visit(Wheel) (as opposed to visit(Engine) etc.) can be

* made during compile time since 'this' is known at compile

* time to be a Wheel. Moreover, each implementation of

* CarElementVisitor implements the visit(Wheel), which is

* another decision that is made at run time. This can be

* considered the *second* dispatch.

*/

visitor.visit(this);

}

}

class CarElementDoVisitor implements CarElementVisitor {

public void visit(final Body body) {

System.out.println("Moving my body");

}

public void visit(final Car car) {

System.out.println("Starting my car");

}

public void visit(final Wheel wheel) {

System.out.println("Kicking my " + wheel.getName() + " wheel");

}

public void visit(final Engine engine) {

System.out.println("Starting my engine");

}

}

class CarElementPrintVisitor implements CarElementVisitor {

public void visit(final Body body) {

System.out.println("Visiting body");

}

public void visit(final Car car) {

System.out.println("Visiting car");

}

public void visit(final Engine engine) {

System.out.println("Visiting engine");

}

public void visit(final Wheel wheel) {

System.out.println("Visiting " + wheel.getName() + " wheel");

}

}

public class VisitorDemo {

public static void main(final String[] args) {

final Car car = new Car();

car.accept(new CarElementPrintVisitor());

car.accept(new CarElementDoVisitor());

}

}

A more flexible approach to this pattern is to create a wrapper class implementing the interface defining the accept method. The wrapper contains a reference pointing to the ICarElement that could be initialized through the constructor. This approach avoids having to implement an interface on each element. See article Java Tip 98 article below

Output

Visiting front left wheel Visiting front right wheel Visiting back left wheel Visiting back right wheel Visiting body Visiting engine Visiting car Kicking my front left wheel Kicking my front right wheel Kicking my back left wheel Kicking my back right wheel Moving my body Starting my engine Starting my car

Common Lisp example

Sources

(defclass auto ()

((elements :initarg :elements)))

(defclass auto-part ()

((name :initarg :name :initform "<unnamed-car-part>")))

(defmethod print-object ((p auto-part) stream)

(print-object (slot-value p 'name) stream))

(defclass wheel (auto-part) ())

(defclass body (auto-part) ())

(defclass engine (auto-part) ())

(defgeneric traverse (function object other-object))

(defmethod traverse (function (a auto) other-object)

(with-slots (elements) a

(dolist (e elements)

(funcall function e other-object))))

;; do-something visitations

;; catch all

(defmethod do-something (object other-object)

(format t "don't know how ~s and ~s should interact~%" object other-object))

;; visitation involving wheel and integer

(defmethod do-something ((object wheel) (other-object integer))

(format t "kicking wheel ~s ~s times~%" object other-object))

;; visitation involving wheel and symbol

(defmethod do-something ((object wheel) (other-object symbol))

(format t "kicking wheel ~s symbolically using symbol ~s~%" object other-object))

(defmethod do-something ((object engine) (other-object integer))

(format t "starting engine ~s ~s times~%" object other-object))

(defmethod do-something ((object engine) (other-object symbol))

(format t "starting engine ~s symbolically using symbol ~s~%" object other-object))

(let ((a (make-instance 'auto

:elements `(,(make-instance 'wheel :name "front-left-wheel")

,(make-instance 'wheel :name "front-right-wheel")

,(make-instance 'wheel :name "rear-left-wheel")

,(make-instance 'wheel :name "rear-right-wheel")

,(make-instance 'body :name "body")

,(make-instance 'engine :name "engine")))))

;; traverse to print elements

;; stream *standard-output* plays the role of other-object here

(traverse #'print a *standard-output*)

(terpri) ;; print newline

;; traverse with arbitrary context from other object

(traverse #'do-something a 42)

;; traverse with arbitrary context from other object

(traverse #'do-something a 'abc))

Output

"front-left-wheel" "front-right-wheel" "rear-right-wheel" "rear-right-wheel" "body" "engine" kicking wheel "front-left-wheel" 42 times kicking wheel "front-right-wheel" 42 times kicking wheel "rear-right-wheel" 42 times kicking wheel "rear-right-wheel" 42 times don't know how "body" and 42 should interact starting engine "engine" 42 times kicking wheel "front-left-wheel" symbolically using symbol ABC kicking wheel "front-right-wheel" symbolically using symbol ABC kicking wheel "rear-right-wheel" symbolically using symbol ABC kicking wheel "rear-right-wheel" symbolically using symbol ABC don't know how "body" and ABC should interact starting engine "engine" symbolically using symbol ABC

Notes

The other-object parameter is superfluous in traverse. The reason is that it is possible to use an anonymous function that calls the desired target method with a lexically captured object:

(defmethod traverse (function (a auto)) ;; other-object removed

(with-slots (elements) a

(dolist (e elements)

(funcall function e)))) ;; from here too

;; ...

;; alternative way to print-traverse

(traverse (lambda (o) (print o *standard-output*)) a)

;; alternative way to do-something with

;; elements of a and integer 42

(traverse (lambda (o) (do-something o 42)) a)

Now, the multiple dispatch occurs in the call issued from the body of the anonymous function, and so traverse is just a mapping function that distributes a function application over the elements of an object. Thus all traces of the Visitor Pattern disappear, except for the mapping function, in which there is no evidence of two objects being involved. All knowledge of there being two objects and a dispatch on their types is in the lambda function.

Python example

Sources

"""

Visitor pattern example.

"""

from abc import ABCMeta, abstractmethod

NOT_IMPLEMENTED = "You should implement this."

class CarElement:

__metaclass__ = ABCMeta

@abstractmethod

def accept(self, visitor):

raise NotImplementedError(NOT_IMPLEMENTED)

class CarElementVisitor:

__metaclass__ = ABCMeta

@abstractmethod

def visit(self, element):

raise NotImplementedError(NOT_IMPLEMENTED)

class Body(CarElement):

def accept(self, visitor):

visitor.visit(self)

class Engine(CarElement):

def accept(self, visitor):

visitor.visit(self)

class Wheel(CarElement):

def __init__(self, name):

self.name = name

def accept(self, visitor):

visitor.visit(self)

class Car(CarElement):

def __init__(self):

self.elements = [

Wheel("front left"), Wheel("front right"),

Wheel("back left"), Wheel("back right"),

Body(), Engine()

]

def accept(self, visitor):

for element in self.elements:

element.accept(visitor)

visitor.visit(self)

class CarElementDoVisitor(CarElementVisitor):

element_type = None

def visit(self, element):

self.element_type = type(element)

if self.element_type == Body:

print("Moving my body.")

elif self.element_type == Car:

print("Starting my car.")

elif self.element_type == Wheel:

print("Kicking my {} wheel.".format(element.name))

elif self.element_type == Engine:

print("Starting my engine.")

else:

raise NotImplementedError(

"Not implemented for type {}.".format(self.element_type)

)

class CarElementPrintVisitor(CarElementVisitor):

element_type = None

def visit(self, element):

self.element_type = type(element)

if self.element_type == Body:

print("Visiting body.")

elif self.element_type == Car:

print("Visiting car.")

elif self.element_type == Wheel:

print("Visiting {} wheel.".format(element.name))

elif self.element_type == Engine:

print("Visiting engine.")

else:

raise NotImplementedError(

"Not implemented for type {}.".format(self.element_type)

)

car = Car()

car.accept(CarElementPrintVisitor())

car.accept(CarElementDoVisitor())

Output

Visiting front left wheel.

Visiting front right wheel.

Visiting back left wheel.

Visiting back right wheel.

Visiting body.

Visiting engine.

Visiting car.

Kicking my front left wheel.

Kicking my front right wheel.

Kicking my back left wheel.

Kicking my back right wheel.

Moving my body.

Starting my engine.

Starting my car.Related design patterns

- Iterator pattern – defines a traversal principle like the visitor pattern, without making a type differentiation within the traversed objects

See also

References

- ^ a b Erich Gamma, Richard Helm, Ralph Johnson, John Vlissides (1994). Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software. Addison Wesley. pp. 331ff. ISBN 0-201-63361-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "The Visitor design pattern - Problem, Solution, and Applicability". w3sDesign.com. Retrieved 2017-08-12.

- ^ Visitor pattern real-world example

- ^ "The Visitor design pattern - Structure and Collaboration". w3sDesign.com. Retrieved 2017-08-12.

External links

- The Visitor Family of Design Patterns at the Wayback Machine (archived October 22, 2015). Additional archives: April 12, 2004, March 5, 2002. A rough chapter from The Principles, Patterns, and Practices of Agile Software Development, Robert C. Martin, Prentice Hall

- Visitor pattern in UML and in LePUS3 (a Design Description Language)

- Article "Componentization: the Visitor Example by Bertrand Meyer and Karine Arnout, Computer (IEEE), vol. 39, no. 7, July 2006, pages 23-30.

- Article A Type-theoretic Reconstruction of the Visitor Pattern

- Article "The Essence of the Visitor Pattern" by Jens Palsberg and C. Barry Jay. 1997 IEEE-CS COMPSAC paper showing that accept() methods are unnecessary when reflection is available; introduces term 'Walkabout' for the technique.

- Article "A Time for Reflection" by Bruce Wallace – subtitled "Java 1.2's reflection capabilities eliminate burdensome accept() methods from your Visitor pattern"

- Visitor Patterns as a universal model of terminating computation.

- Visitor Pattern using reflection(java).

- PerfectJPattern Open Source Project, Provides a context-free and type-safe implementation of the Visitor Pattern in Java based on Delegates.

- Visitor Design Pattern

- Article Java Tip 98: Reflect on the Visitor design pattern