Basilica: Difference between revisions

GPinkerton (talk | contribs) restoring baseless removals |

GPinkerton (talk | contribs) Changing short description from "Building used as a place of Christian worship, or a type of large building in classical architecture" to "Form of large public building in classical architecture and type of church" (Shortdesc helper) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{short description| |

{{short description|Form of large public building in classical architecture and type of church}} |

||

{{About|a form of building|the designation "basilica" in canon law|Basilicas in Roman Catholicism| the Byzantine code of law|Basilika|the genus of moth|Basilica (moth)| the herb|Basil}} |

{{About|a form of building|the designation "basilica" in canon law|Basilicas in Roman Catholicism| the Byzantine code of law|Basilika|the genus of moth|Basilica (moth)| the herb|Basil}} |

||

[[File:BasilicaSemproniaReconstruction.jpg|thumb|Digital reconstruction of the 2nd century BC [[Basilica Sempronia]], in the [[Forum Romanum]].]] |

[[File:BasilicaSemproniaReconstruction.jpg|thumb|Digital reconstruction of the 2nd century BC [[Basilica Sempronia]], in the [[Forum Romanum]].]] |

||

Revision as of 07:38, 9 May 2020

The Latin word basilica refers to large public buildings with multiple functions in Ancient Roman architecture, typically built alongside the town's forum. The basilica was in the Latin West equivalent to the Stoa in the Greek East. It also refers to the typical architectural form of basilicas.

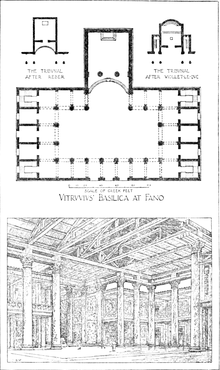

Originally, the word was used to refer to an ancient Roman public building, where courts were held, as well as serving other official and public functions. Basilicas are typically rectangular buildings with a central nave flanked by two or more longitudinal aisles, with the roof at two levels, being higher in the centre over the nave to admit a clerestory and lower over the side-aisles. An apse at one end, or less frequently at both ends or on the side, usually contained the raised tribunal occupied by the Roman magistrates.

The basilica was centrally located in every Roman town, usually adjacent to the main forum. Subsequently, the basilica was not built near a forum but adjacent to a palace and was known as a "palace basilica".

Secondly, as the Roman Empire adopted Christianity, the major church buildings were typically constructed with this basic architectural plan and thus it became popular throughout Europe. It continues to be used in an architectural sense to describe rectangular buildings with a central nave and aisles, and usually a raised platform at the opposite end from the door. In Europe and the Americas the basilica remained the most common architectural style for churches of all Christian denominations, though this building plan has become less dominant in new buildings since the latter 20th century.

Terminology

The Latin word basilica Ancient Greek: βασιλική στοά, romanized: basilikè stoá, lit. 'royal stoa'. In Rome the word was at first used to describe an ancient Roman public building where courts were held, as well as serving other official and public functions. To a large extent these were the town halls of ancient Roman life. The basilica was centrally located in every Roman town, usually adjacent to the main forum. These buildings, an example of which is the Basilica Ulpia, were rectangular, and often had a central nave and aisles, usually with a slightly raised platform and an apse at each of the two ends, adorned with a statue perhaps of the emperor, while the entrances were from the long sides.[1][2]

By extension the name was applied to Christian churches which adopted the same basic plan and it continues to be used as an architectural term to describe such buildings, which form the majority of church buildings in Western Christianity, though the basilican building plan became less dominant in new buildings from the later 20th century.

Architecture

The Roman basilica was a large public building where business or legal matters could be transacted. The first basilicas had no religious function at all. As early as the time of Augustus, a public basilica for transacting business had been part of any settlement that considered itself a city, used in the same way as the covered market houses of late medieval northern Europe, where the meeting room, for lack of urban space, was set above the arcades, however. Although their form was variable, basilicas often contained interior colonnades that divided the space, giving aisles or arcaded spaces on one or both sides, with an apse at one end (or less often at each end), where the magistrates sat, often on a slightly raised dais. The central aisle tended to be wide and was higher than the flanking aisles, so that light could penetrate through the clerestory windows.

The oldest known basilica, the Basilica Porcia, was built in Rome in 184 BC by Cato the Elder during the time he was Censor. Other early examples include the basilica at Pompeii (late 2nd century BC).

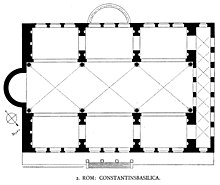

Probably the most splendid Roman basilica (see below) is the one begun for traditional purposes during the reign of the pagan emperor Maxentius and finished by Constantine I after AD 313.

Basilicas in the Roman Forum

- Basilica Porcia: first basilica built in Rome (184 BC), erected on the personal initiative and financing of the censor Marcus Porcius Cato (Cato the Elder) as an official building for the tribunes of the plebs

- Basilica Aemilia, built by the censor Aemilius Lepidus in 179 BC

- Basilica Sempronia, built by the censor Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus in 169 BC

- Basilica Opimia, erected probably by the consul Lucius Opimius in 121 BC, at the same time that he restored the temple of Concord (Platner, Ashby 1929)

- Basilica Julia, initially dedicated in 46 BC by Julius Caesar and completed by Augustus 27 BC to AD 14

- Basilica Argentaria, erected under Trajan, emperor from AD 98 to 117

- Basilica of Maxentius and Constantine (built between AD 308 and 312)

Palace basilicas

In the Roman Imperial period (after about 27 BC), a basilica for large audiences also became a feature in palaces. In the 3rd century of the Christian era, the governing elite appeared less frequently in the forums.

They now tended to dominate their cities from opulent palaces and country villas, set a little apart from traditional centers of public life. Rather than retreats from public life, however, these residences were the forum made private.(Peter Brown, in Paul Veyne, 1987)

Seated in the tribune of his basilica, the great man would meet his dependent clientes early every morning.

Constantine's basilica at Trier, the Aula Palatina (AD 306), is still standing. A private basilica excavated at Bulla Regia (Tunisia), in the "House of the Hunt", dates from the first half of the 5th century. Its reception or audience hall is a long rectangular nave-like space, flanked by dependent rooms that mostly also open into one another, ending in a semi-circular apse, with matching transept spaces. Clustered columns emphasised the "crossing" of the two axes.

Christian adoption of the basilica form

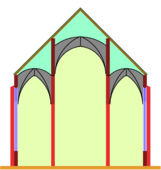

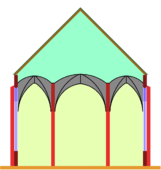

Variations: Where the roofs have a low slope, the triforium gallery may have own windows or may be missing

The remains of a large subterranean Neopythagorean basilica dating from the 1st century of the Christian era were found near the Porta Maggiore in Rome in 1915. The ground-plan of Christian basilicas in the 4th century was similar to that of this Neopythagorean basilica, which had three naves and an apse.

In the 4th century, once the Imperial authorities had decriminalised Christianity with the 313 Edict of Milan, and with the activities of Constantine the Great and his mother Helena, Christians were prepared to build larger and more handsome edifices for worship than the furtive meeting-places (such as the Cenacle, cave-churches, house churches such as that of the martyrs John and Paul) they had been using. Architectural formulas for temples were unsuitable due to their pagan associations, and because pagan cult ceremonies and sacrifices occurred outdoors under the open sky in the sight of the gods, with the temple, housing the cult figures and the treasury, as a backdrop. The usable model at hand, when Constantine wanted to memorialise his imperial piety, was the familiar conventional architecture of the basilicas.[3]

There were several variations of the basic plan of the secular basilica, always some kind of rectangular hall, but the one usually followed for churches had a central nave with one aisle at each side and an apse at one end opposite to the main door at the other end. In (and often also in front of) the apse was a raised platform, where the altar was placed, and from where the clergy officiated. In secular building this plan was more typically used for the smaller audience halls of the emperors, governors, and the very rich than for the great public basilicas functioning as law courts and other public purposes.[4] Constantine built a basilica of this type in his palace complex at Trier, later very easily adopted for use as a church. It is a long rectangle two storeys high, with ranks of arch-headed windows one above the other, without aisles (there was no mercantile exchange in this imperial basilica) and, at the far end beyond a huge arch, the apse in which Constantine held state.

Comparison of profiles of churches

-

Basilical structure: The central nave extends to one or two storeys more than the lateral aisles, and it has upper windows.

-

Pseudobasilica (i. e. false basilica): The central nave extends to an additional storey, but it has no upper windows.

-

Stepped hall: The vaults of the central nave begin a bit higher than those of the lateral aisles, but there is no additional storey.

-

Hall church: All vaults are almost on the same level.

Development

Putting an altar instead of the throne, as was done at Trier, made a church. Basilicas of this type were built in western Europe, Greece, Syria, Egypt, and Palestine, that is, at any early centre of Christianity. Good early examples of the architectural basilica include the Church of the Nativity at Bethlehem (6th century), the church of St Elias at Thessalonica (5th century), and the two great basilicas at Ravenna.

The first basilicas with transepts were built under the orders of Emperor Constantine, both in Rome and in his "New Rome", Constantinople:

- "Around 380, Gregory Nazianzen, describing the Constantinian Church of the Holy Apostles at Constantinople, was the first to point out its resemblance to a cross. Because the cult of the cross was spreading at about the same time, this comparison met with stunning success." (Yvon Thébert, in Veyne, 1987)

Thus, a Christian symbolic theme was applied quite naturally to a form borrowed from civil semi-public precedents. The first great Imperially sponsored Christian basilica is that of St John Lateran, which was given to the Bishop of Rome by Constantine right before or around the Edict of Milan in 313 and was consecrated in the year 324. In the later 4th century, other Christian basilicas were built in Rome: Santa Sabina, and St Paul's Outside the Walls (4th century), and later St Clement (6th century).

A Christian basilica of the 4th or 5th century stood behind its entirely enclosed forecourt ringed with a colonnade or arcade, like the stoa or peristyle that was its ancestor or like the cloister that was its descendant. This forecourt was entered from outside through a range of buildings along the public street. This was the architectural ground-plan of St. Peter's Basilica in Rome, until in the 15th century it was demolished to make way for a modern church built to a new plan.

In most basilicas, the central nave is taller than the aisles, forming a row of windows called a clerestory. Some basilicas in the Caucasus, particularly those of Armenia and Georgia, have a central nave only slightly higher than the two aisles and a single pitched roof covering all three. The result is a much darker interior. This plan is known as the "oriental basilica", or "pseudobasilica" in central Europe. A peculiar type of basilica, known as three-church basilica, was developed in early medieval Georgia, characterized by the central nave which is completely separated from the aisles with solid walls.[5]

Gradually, in the Early Middle Ages there emerged the massive Romanesque churches, which still kept the fundamental plan of the basilica.

In the United States the style was copied with variances. An American church built imitating the architecture of an Early Christian basilica, St. Mary's (German) Church in Pennsylvania, was demolished in 1997.

-

Old St Peter's, Rome, as the 4th-century basilica had developed by the mid-15th century, in a 19th-century reconstruction

-

Nave of the Saint Sofia Church - second oldest church in the Bulgarian capital Sofia, dating to the 4th-6th century.

-

St. Sebald's in Nuremberg has a basilical nave and a hall choir

-

Palma Cathedral on Mallorca in Spain has windows on three levels, one above the aisles, one above the file of chapels and one in the chapels.

-

A rare American church built imitating the architecture of an Early Christian basilica, St. Mary's (German) Church in Pennsylvania, now demolished.

Basilicas in Eastern Orthodoxy

In the Eastern Orthodox Church, in general, the basilica is a mere architectural description of churches built in the ancient style. It bears no significance with regard to precedence or importance of the particular building or clerics associated with it. Eastern basilicas may be single-naved, or have the nave flanked by one or two pairs of lower aisles; it may have a dome in the middle: in this case, it is called a "domed basilica".

In Romania, the word for church both as a building and as an institution is biserică, derived from the term basilica.

The style influenced the construction of early wooden churches.

Basilicas in Roman Catholicism

In the Roman Catholic Church the term basilica refers to an official designation of a certain kind of church in the Roman Catholic Church: a large and important place of worship that has been given special ceremonial rights by the Pope. They need not architecturally be basilicas. Basilicas in this sense are divided into classes, the major ("greater") basilicas and the minor basilicas. Churches designated as papal basilicas, in particular, possess a papal throne and a papal high altar, at which no one may celebrate Mass without the pope's permission.[6]

See also

- Architecture of cathedrals and great churches

- Duomo

- List of basilicas

- Roman architecture

- Roman Catholic Marian churches

References and sources

- References

- ^ The Oxford Dictionary of Christian Art and Architecture (2013 ISBN 978-0-19968027-6), p. 117

- ^ "The Institute for Sacred Architecture - Articles - The Eschatological Dimension of Church Architecture". www.sacredarchitecture.org.

- ^ "Basilica Plan Churches". Cartage.org.lb. Archived from the original on 12 January 2012. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- ^ Syndicus, 40

- ^ Loosley Leeming, Emma (2018). Architecture and Asceticism: Cultural Interaction between Syria and Georgia in Late Antiquity. Texts and Studies in Eastern Christianity, Volume: 13. Brill. pp. 115–121. ISBN 978-90-04-37531-4.

- ^ Gietmann, G.; Thurston, Herbert (1913). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Unknown parameter|last-author-amp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help)

- Sources

- Krautheimer, Richard (1992). Early Christian and Byzantine architecture. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-05294-4.

- Architecture of the basilica

- Syndicus, Eduard, Early Christian Art, Burns & Oates, London, 1962

- Basilica Porcia

- W. Thayer, "Basilicas of Ancient Rome": from Samuel Ball Platner (as completed and revised by Thomas Ashby), 1929. A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome (London: Oxford University Press)

- Paul Veyne, ed. A History of Private Life I: From Pagan Rome to Byzantium, 1987

- Heritage Foundation of Newfoundland and Labrador

- Gietmann, G.; Thurston, Herbert (1913). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Unknown parameter|last-author-amp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help)

External links

Media related to Basilicas at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Basilicas at Wikimedia Commons- List of All Major, Patriarchal and Minor Basilicas & statistics by Giga-Catholic Information