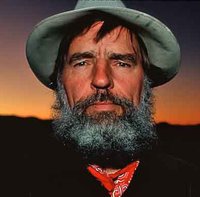

Edward Abbey

Edward Abbey | |

|---|---|

| |

| Occupation | Essayist, Novelist |

Edward Paul Abbey (January 29, 1927 – March 14, 1989) was an American author and essayist noted for his advocacy of environmental issues, criticism of public land policies, and anarchist political views. His best-known works include the novel The Monkey Wrench Gang, which has been cited as an inspiration by radical environmental groups, and the non-fiction work Desert Solitaire. Writer Larry McMurtry referred to Abbey as the "Thoreau of the American West".

Early life and education

Abbey was born in Indiana, Pennsylvania on January 29, 1927. He grew up in nearby Home, Pennsylvania, where there is a Pennsylvania state historical marker in his honor.[1] This Appalachian upbringing influenced him throughout his life, and he addressed it at various points in his writing, most extensively in The Fool's Progress and Appalachian Wilderness. [citation needed]

Abbey graduated from high school in Indiana, Pennsylvania in 1945. Eight months before his 18th birthday, when he would be faced with being drafted into the United States military, Abbey decided to explore the American southwest. He travelled by foot, bus, hitchhiking, and freight train hopping.[2] During this trip he fell in love with the desert country of the Four Corners region. Abbey wrote: "[...]crags and pinnacles of naked rock, the dark cores of ancient volcanoes, a vast and silent emptiness smoldering with heat, color, and indecipherable significance, above which floated a small number of pure, clear, hard-edged clouds. For the first time, I felt I was getting close to the West of my deepest imaginings, the place where the tangible and the mythical became the same."[3][4][5]

Upon his return, Abbey was drafted into the military, where he served two years as a military police officer in Italy, after which he was honorably discharged.[2]

When he returned to the United States, Abbey took advantage of the G.I. Bill to attend the University of New Mexico, where he received a B.A. in philosophy and English in 1951, and a Master's degree in philosophy in 1956.[2][6][7] During his time in college, Abbey supported himself by working at a variety of odd jobs, including being a newspaper reporter and bartending in Taos, New Mexico. During this time, he had few male friends, but had intimate relationships with a number of women. Shortly before getting his bachelors degree, Abbey married his first wife, Jean Schmechal (another UNM student).[8] While an undergraduate, Abbey was the editor of a student newspaper in which he published an article titled "Some Implications of Anarchy". A cover quotation of the article, "ironically attributed to Louisa May Alcott" stated "Man will never be free until the last king is strangled with the entrails of the last priest." University officials seized all of the copies of the issue, and removed Abbey from the editorship of the paper.[9] After graduating, Schmechal and Abbey traveled together to Edinburgh, Scotland[8], where Abbey spent a year at Edinburgh University as a Fulbright scholar.[6][8] During this time, Abbey and Schmechal separated and ended their marriage.[8]

Abbey's master's thesis explored anarchism and the morality of violence, asking the two questions: "To what extent is the current association between anarchism and violence warranted?" and "In so far as the association is a valid one, what arguments have the anarchists presented, explicitly or implicitly, to justify the use of violence?".[10]

After receiving his masters degree, Abbey spent 1957 at Stanford University on a Wallace Stegner Creative Writing Fellowship.[6]

Work for National Park Service

In 1956 and 1957, Abbey worked as a seasonal ranger for the United States National Park Service at Arches National Monument (now a national park), near the town of Moab, Utah. Abbey's held the position from April to September each year, during which time he maintained trails, greeted visitors, and collected campground fees. He lived in a house trailer that had been provided to him by the Park Service, as well as in a ramada that he built himself. During his stay at Arches, Abbey accumulated a large volume of notes and sketches which later formed the basis of his first non-fiction work, Desert Solitaire.[11]

In the 1960s Abbey worked as a seasonal park ranger at Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, on the border of Arizona and Mexico. [citation needed]

On October 16, 1965 Abbey married Judy Pepper, who accompanied Abbey as a seasonal park ranger in the Florida Everglades, and then as a fire lookout in Lassen Volcanic National Park.[12] Abbey and Pepper had a daughter together, named Susie. Judy was separated from Abbey for extended periods of time while she attended the University of Arizona to get her master's degree. During this time, Abbey slept with other women -- something that Judy gradually became aware of, causing their marriage to suffer.[13] Judy died of leukemia on July 11, 1970, an event that crushed Abbey, causing him to go into "bouts of depression and loneliness" for years. It was to Judy that he dedicated his book Black Sun. However, the book was not an autobiographical novel about his relationship with Judy. Rather it was a story about a woman with whom Abbey had an affair in 1963. Abbey finished the first draft of Black Sun in 1968, two years before Judy died, and it was "a bone of contention in their marriage".[14][15]

Literature

Desert Solitaire, Abbey's fourth book and first non-fiction work, was published in 1968. In it, he describes his stay in the canyonlands of southeastern Utah from 1956-1957.[16] Desert Solitaire is regarded as one of the finest nature narratives in American literature, and has been compared to Aldo Leopold's A Sand County Almanac[citation needed] and Thoreau's Walden.[17] In it, Abbey vividly describes the physical landscapes of Southern Utah and delights in his isolation as a back country park ranger, recounting adventures in the nearby canyon country and mountains. He also attacks what he terms the "industrial tourism" and resulting development in the national parks ("national parking lots"), rails against the Glen Canyon Dam, and comments on various other subjects.[citation needed]

Regarding his writing style, Abbey states: "I write in a deliberately provocative and outrageous manner because I like to startle people. I hope to wake up people. I have no desire to simply soothe or please. I would rather risk making people angry than putting them to sleep. And I try to write in a style that's entertaining as well as provocative. It's hard for me to stay serious for more than half a page at a time."[18] Abbey felt that it was the duty of all authors to "speak the truth--especially unpopular truth. Especially truth that offends the powerful, the rich, the well-established, the traditional, the mythic".[19] His abrasiveness, opposition to anthropocentrism, and outspoken writings made him the object of much controversy.[citation needed] Agrarian author Wendell Berry claimed that Abbey was regularly criticized by mainstream environmental groups because Abbey often advocated controversial positions that were very different from those which environmentalists were commonly expected to hold.[20]

It is often stated that Abbey's works played a significant role in precipitating the creation of Earth First!.[21] The Monkeywrench Gang inspired environmentalists frustrated with mainstream environmentalist groups and what they saw as unacceptable compromises. Earth First! was formed as a result in 1980, advocating eco-sabotage or "monkeywrenching." Although Abbey never officially joined the group, he became associated with many of its members, and occasionally wrote for the organization[22]

Abbey's own influences included Aldo Leopold, Henry David Thoreau, and A.B. Guthrie, Jr..[23]

Political views

Sometimes called the "desert anarchist," Abbey was known to anger people of all political stripes, including environmentalists. In his essays the narrator describes throwing beer cans out of his car, claiming the highway had already littered the landscape.[citation needed] Abbey had an FBI file opened on him in 1947, after he posted a letter while in college urging people to rid themselves of their draft cards.[24]

In autumn of 1987, the Utne Reader published a letter by Murray Bookchin which claimed that Abbey, Garrett Hardin, and the members of Earth First! were racists and eco-terrorists. Abbey was extremely offended, and demanded a public apology, stating that he was neither racist nor a supporter of terrorism. All three of those Bookchin labelled "racist" opposed illegal immigration into the United States, contending that population growth would cause further harm to the environment. Regarding the accusation of "eco-terrorism", Abbey responded that the tactics he supported were trying to defend against the terrorism he felt was committed by government and industry against living beings and the environment.[25] He devoted one chapter in his book Hayduke Lives to poking fun at left-green leader Murray Bookchin. However, he reserved his harshest criticism for the military-industrial complex, "welfare ranchers," energy companies, land developers and "Chambers of Commerce," all of which he believed were destroying the West's great landscapes.[citation needed]

Death and burial

Edward Abbey died on March 14, 1989,[26] at the age of 62, in his home in Tucson, Arizona. His death was due to complications from surgery; he suffered four days of esophageal hemorrhaging, due to esophageal varices, a recurrent problem with one group of veins.[27] Showing his sense of humor, he left a message for anyone who asked about his final words: "No comment." Abbey also left instructions on what to do with his remains: Abbey wanted his body transported in the bed of a pickup truck, and wished to be buried as soon as possible. He did not want to be embalmed or placed in a coffin. Instead, he preferred to be placed inside of an old sleeping bag, and requested that his friends disregard all state laws concerning burial. "I want my body to help fertilize the growth of a cactus or cliff rose or sagebrush or tree." said the message. For his funeral, Abbey stated "No formal speeches desired, though the deceased will not interfere if someone feels the urge. But keep it all simple and brief." He requested gunfire and bagpipe music, a cheerful and raucous wake, "[a]nd a flood of beer and booze! Lots of singing, dancing, talking, hollering, laughing, and lovemaking."[27][28]

A 2003 Outside article[specify] described how his friends honored his request:

"The last time Ed smiled was when I told him where he was going to be buried," says Doug Peacock, an environmental crusader in Edward Abbey's inner circle. On March 14, 1989, the day Abbey died from esophageal bleeding at 62, Peacock, along with his friend Jack Loeffler, his father-in-law Tom Cartwright, and his brother-in-law Steve Prescott, wrapped Abbey's body in his blue sleeping bag, packed it with dry ice, and loaded Cactus Ed into Loeffler's Chevy pickup. After stopping at a liquor store in Tucson for five cases of beer, and some whiskey to pour on the grave, they drove off into the desert. The men searched for the right spot the entire next day and finally turned down a long rutted road, drove to the end, and began digging. That night they buried Ed and toasted the life of America's prickliest and most outspoken environmentalist.

Abbey's body was buried in the Cabeza Prieta Desert in Pima County, Arizona, where "you'll never find it." The friends carved a marker on a nearby stone, reading:

PAUL

ABBEY

1927—1989

No Comment[29][30]In late March, about 200 friends of Abbey's gathered near the Saguaro National Monument near Tucson and held the wake he requested. A second, much larger wake was held in May, just outside his beloved Arches National Park, with such notables as Terry Tempest Williams and Wendell Berry speaking.[citation needed]

Abbey is survived by two daughters, Susannah and Becky; and three sons, Joshua, Aaron and Benjamin.[citation needed]

Works

Fiction

- Jonathan Troy (1954) (ISBN 1-131-40684-2)

- The Brave Cowboy (1956) (ISBN 0-8263-0448-6)

- Fire on the Mountain (1962) (ISBN 0-8263-0457-5)

- Black Sun (1971) (ISBN 0-88496-167-2)

- The Monkey Wrench Gang (1975) (ISBN 0-397-01084-2)

- Good News (1980) (ISBN 0-525-11583-8)

- The Fool's Progress (1988) (ISBN 0-8050-0921-3)

- Hayduke Lives (1989) (ISBN 0-316-00411-1)

- Earth Apples: The Poetry of Edward Abbey (1994) (ISBN 0-312-11265-3)

Non-fiction

- Desert Solitaire: A Season in the Wilderness (1968) (ISBN 0-8165-1057-1)

- Appalachian Wilderness (1970)

- Slickrock (1971) (ISBN 0-87156-051-8)

- Cactus Country (1973)

- The Journey Home (1977) (ISBN 0-525-13753-X)

- The Hidden Canyon (1977)

- Abbey's Road (1979) (ISBN 0-525-05006-X)

- Desert Images (1979)

- Down the River (with Henry Thoreau & Other Friends) (1982) (ISBN 0-525-09524-1)

- In Praise of Mountain Lions (1984)

- Beyond the Wall (1984) (ISBN 0-03-069299-7)

- One Life at a Time, Please (1988) (ISBN 0-8050-0602-8)

- A Voice Crying in the Wilderness: Notes from a Secret Journal (1989)

- Confessions of a Barbarian: Selections from the Journals of Edward Abbey, 1951–1989 (1994) (ISBN 0-316-00415-4)

Letters

- Cactus Chronicles published by Orion Magazine, Jul–Aug 2006 (no longer active,)

- Postcards from Ed (book)|Postcards from Ed: Dispatches and Salvos from an American Iconoclast (2006) (ISBN 1-57131-284-6)

Anthologies

- Slumgullion Stew: An Edward Abbey Reader (1984)

- The Best of Edward Abbey (1984)

- The Serpents of Paradise: A Reader (1995)

See also

- Ecodefense: A Field Guide To Monkeywrenching [book]

References

- Notes

- ^ Historical state marker

- ^ a b c Peterson, David (2003). Confessions of a barbarian: selections from the journals of Edward Abbey. Johnson Books. p. 1. ISBN 9781555662875.

- ^ Ronald, Ann (2000). The New West of Edward Abbey. University of Nevada Press. p. 59. ISBN 9780874173574.

- ^ Western Literature Association (1987). "Edward Abbey". A Literary history of the American West. TCU Press. p. 604. ISBN 9780875650210.

- ^ For Abbey's full account of this trip, see his essay "Hallelujah on the Bum"

- ^ a b c Ronald, Ann (2000). The New West of Edward Abbey. University of Nevada Press. p. 247. ISBN 9780874173574.

- ^ For a detailed discussion of Abbey's college years, see Bishop, James (1995). "The Anarchist Emerges". Epitaph for a desert anarchist: the life and legacy of Edward Abbey. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9780684804392.

- ^ a b c d Bishop, James (1995). Epitaph for a desert anarchist: the life and legacy of Edward Abbey. Simon & Schuster. pp. 88–89. ISBN 9780684804392.

- ^ Scheese, Don (2002). Nature writing: the pastoral impulse in America. Psychology Press. p. 108. ISBN 9780415938891.

- ^ Phillipon, Daniel J. (2005). "Toward Ecotopia: Edward Abbey and Earth First!". Conserving Words: How American Nature Writers Shaped the Environmental Movement. University of Georgia Press. pp. 225–226. ISBN 9780820327594.

- ^ Scheese, Don (1998). "Desert Solitaire: Counter-Friction to the Machine in the Garden". The ecocriticism reader: landmarks in literary ecology. University of Georgia Press. p. 305. ISBN 9780820317816.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ Loeffler, Jack (2003). Adventures with Ed: A Portrait of Abbey. University of New Mexico Press. pp. 86–87. ISBN 9780826323880.

- ^ Loeffler, Jack (2003). Adventures with Ed: A Portrait of Abbey. University of New Mexico Press. p. 92. ISBN 9780826323880.

- ^ Pozza, David M. (2006). Bedrock and paradox: the literary landscape of Edward Abbey. Peter Lang. pp. 72–73. ISBN 9780820463308.

- ^ Bishop, James (1995). Epitaph for a desert anarchist: the life and legacy of Edward Abbey. Simon & Schuster. p. 155. ISBN 9780684804392.

- ^ Pozza, David M. (2006). Bedrock and paradox: the literary landscape of Edward Abbey. Peter Lang. p. 13. ISBN 9780820463308.

- ^ Olson, Ted (2000). ""In Search of a More Human Nature": Wendell Berry's Revision of Thoreau's Experiment". In Schneider, Richard J. (ed.). Thoreau's sense of place: essays in American environmental writing. University of Iowa Press. p. 63. ISBN 9780877457084.

- ^ Trimble, Stephen, ed. (1995). "Introduction". Words from the land: encounters with natural history writing. University of Nevada Press. p. 27. ISBN 9780874172645.

- ^ Moore, Brian L. (2008). Ecology and literature: ecocentric personification from antiquity to the twenty-first century. Macmillan. p. 174. ISBN 9780230606692.

- ^ Nelson, Barney (2000). The wild and the domestic: animal representation, ecocriticism, and western American literature. University of Nevada Press. p. 92. ISBN 9780874173475.

- ^ Taylor, Bron (1995). "Resacralizing Earth: Pagan Environmentalism and the Restoration of Turtle Island". American sacred space. Indiana University Press. p. 105. ISBN 9780253210067.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ Peterson, David, ed. (2006). Postcards From Ed: Dispatches and Salvos from an American Iconoclast. (publisher?). p. [page needed].

- ^ Bishop, James (1995). Epitaph for a desert anarchist: the life and legacy of Edward Abbey. Simon & Schuster. pp. 221–222. ISBN 9780684804392.

- ^ FBI response to Freedom of Information Act request for its file on Abbey

- ^ Loeffler, Jack (2003). Adventures with Ed: A Portrait of Abbey. University of New Mexico Press. p. 260. ISBN 9780826323880.

- ^ Trimble, Stephen (1995). "Epilogue: Remembering Edward Abbey". Words from the land: encounters with natural history writing. University of Nevada Press. p. 390. ISBN 9780874172645.

- ^ a b "Edward Abbey: (1927-1989)". Environmental activists. Greenwood Publishing Group. 2001. p. 4. ISBN 9780313308840.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Quammen, David, "Bagpipes for Ed", Outside, April 1989

- ^ Kowalewski, Michael (1996). "Introduction". In Kowalewski, Michael (ed.). Reading the West: New Essays on the Literature of the American West. Cambridge University Press. p. 16. ISBN 9780521565592.

- ^ Peterson, David (1997). The nearby faraway: a personal journey through the heart of the West. Big Earth Publishing. p. 88. ISBN 9781555661878.

- Further reading

- Cahalan, James M. (2003). Edward Abbey: A Life. University of Arizona Press. ISBN 9780816522675.

- Knott, John Ray (2002). "Edward Abbey and the Romance of the Wilderness". Imagining wild America. University of Michigan. ISBN 9780472068067.

- Lane, Belden C. (2002). "Mythic Landscapes: The Desert Imagination of Edward Abbey". Landscapes of the sacred: geography and narrative in American spirituality. JHU Press. ISBN 9780801868382.

- McClintock, James I. (1994). "Edward Abbey: "An Earthiest"". Nature's kindred spirits: Aldo Leopold, Joseph Wood Krutch, Edward Abbey, Annie Dillard, and Gary Snyder. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 9780299141745.

- Meyer, Kurt A. (1987). Edward Abbey: freedom fighter, freedom writer. University of Wyoming Press.

- Payne, Daniel G. (1996). "Monkeywrenching, Environmental Extremism, and the Problematical Edward Abbey". Voices in the wilderness: American nature writing and environmental politics. UPNE. ISBN 9780874517521.

- Quigley, Peter, ed. (1998). Coyote in the maze: tracking Edward Abbey in a world of words. University of Utah Press. ISBN 9780874805635.

- Ronald, Ann (2003). "The Nevada Scene Through Edward Abbey's Eyes". Reader of the purple sage: essays on Western writers and environmental literature. University of Nevada Press. ISBN 9780874175240.

- Slovic, Scott (1992). ""Rudolf the red knows rain, dear": The Aestheticism of Edward Abbey". Seeking awareness in American nature writing: Henry Thoreau, Annie Dillard, Edward Abbey, Wendell Berry, Barry Lopez. University of Utah Press. ISBN 9780874803624.

- Wild, Peter (1999). "Edward Abbey: Ned Ludd Arrives on the Desert". The opal desert: explorations of fantasy and reality in the American Southwest. University of Texas Press. ISBN 9780292791299.

External links

- AbbeyWeb - information about Edward Abbey and his books

- Template:Worldcat id

- Edward Abbey at the Internet Book List

- Edward Abbey at the Internet Book Database of Fiction

- Edward Abbey at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Edward Abbey collected news and commentary at The New York Times

- 1927 births

- 1989 deaths

- Green anarchists

- American anarchists

- American environmentalists

- American essayists

- American nature writers

- American non-fiction environmental writers

- American novelists

- American philosophers

- American political writers

- American conservationists

- People from Indiana, Pennsylvania

- Environmental fiction writers

- History of Pima County, Arizona

- Arches National Park

- United States National Park Service personnel