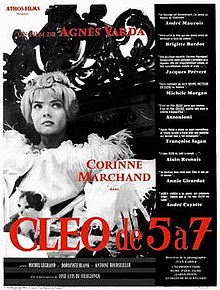

Cléo from 5 to 7

| Cléo from 5 to 7 | |

|---|---|

Original poster | |

| Directed by | Agnès Varda |

| Written by | Agnès Varda |

| Produced by | Georges de Beauregard Carlo Ponti |

| Starring | Corinne Marchand Antoine Bourseiller Dominique Davray Dorothée Blanc Michel Legrand |

| Cinematography | Jean Rabier Alain Levent Paul Bonis |

| Edited by | Pascale Laverrière Janine Verneau |

| Music by | Michel Legrand |

Release date |

|

Running time | 90 minutes |

| Countries | France Italy |

| Language | French |

Cléo from 5 to 7 (Template:Lang-fr [kle.o də sɛ̃k a sɛt]) is a 1962 French Left Bank film written and directed by Agnès Varda.[1] The story starts with a young singer, Florence "Cléo" Victoire, at 5pm on June 21, as she waits until 6:30pm to hear the results of a medical test that will possibly confirm a diagnosis of cancer. The film is known for its handling of several of the themes of existentialism, including discussions of mortality, the idea of despair, and leading a meaningful life. The film has a strong feminine viewpoint belonging to French feminism and raises questions about how women are perceived, especially in French society. Mirrors appear frequently to symbolize self-obsession, which Cléo embodies.

The film includes cameos by Jean-Luc Godard, Anna Karina, Eddie Constantine and Jean-Claude Brialy as characters in the silent film Raoul shows Cléo and Dorothée, while composer Michel Legrand, who wrote the film's score, plays "Bob the pianist". It was entered into the 1962 Cannes Film Festival.[2]

Plot

This film's plot summary may be too long or excessively detailed. (November 2019) |

Cléo Victoire is having a tarot card reading with a fortune teller, who tells her that there is a widow in Cléo's life who is completely devoted to her, but is also a terrible influence (her maid, Angèle). The fortune teller also sees that Cléo has recently met a generous young man, which she confirms, claiming that she doesn't see him too often, but he got her into the music industry. The fortune teller then says that she will meet a talkative young man. There is also an evil force in Cléo's life: a doctor. The fortune teller then pulls the hanged man card, meaning that Cléo is ill, potentially with cancer. She then proceeds to pull the death tarot card, and Cléo requests that the fortune teller read her palm. After examining her lifeline, the fortune teller remains silent before telling Cléo that she does not read hands, leading Cléo to believe that she is doomed.

While distraught from her visit to the fortune teller, Cléo reminds herself "as long as I'm beautiful, I'm alive" and that death is ugly. She meets her maid, Angèle, at a café and recounts the results of the tarot card reading, claiming that if it's cancer, she'll kill herself. Cléo cries in the café, even though there are people around, including the owner of the café. Cléo and Angèle proceed to go hat shopping, where Cléo only pays attention to the black fur hats, despite Angèle constantly reminding her that it's summertime. The black hats all beckon her, and she eventually picks out a black, winter hat. Cléo wants to wear the hat home, but Angèle reminds her that it's Tuesday, and it's bad luck to wear something new on a Tuesday. They have the shopkeeper send the hat to Cléo's home, and Cléo and Angèle take a taxi home in time for Cléo's rehearsal. The taxi driver is a woman, and Cleo and Angele find her to be an interesting character.

On the ride home, one of Cléo's songs plays, and they listen to the radio, discussing current news including the Algerian War, rebels who have been recently arrested, the Vienna Conference, U.S. President John F. Kennedy, and Édith Piaf's recent surgery. Towards the end of the taxi ride, Cléo grows nauseous and attributes it to her illness. Upon returning home, Cléo cannot breathe, and Angèle tells her to do some exercise. Angèle helps her change into her clothes for rehearsal while Cléo is stretching out on a pull-up bar. She then lights a cigarette and relaxes in her bed. Before Cléo's lover, the man who the fortune teller mentioned earlier, enters the building, Angèle tells Cléo not to tell him that she's ill, because men "hate weakness". Her lover, a very busy man, tells her that he only has time to stop by for a kiss and that he'll be able to take her on vacation soon. Cléo tells him that she's ill, but he doesn't take her seriously. Cléo thinks that she's too good to men who are all egoists, to which Angèle agrees.

Once Cléo's lover leaves, Bob, a pianist, and Maurice, a writer, arrive at her home for her rehearsal. Bob and Maurice pretend to be doctors once Angèle tells them that Cléo is ill, because "all women like a good joke." However, Cléo does not find their joke funny, as no one is taking her illness seriously but her. Bob goes to the piano, and they begin to practice some of Cléo's songs. As they practice, Cléo's mood quickly darkens after singing the song "Sans Toi." Cléo feels like all people do is exploit her and that it won't be long until she's just a puppet for the music industry. Saying that everyone spoils her but no one loves her, Cléo leaves everyone behind in her home.

On the way to a café, Cléo passes a street performer swallowing frogs and spitting them back out on a huge wave of water. She plays one of her songs at a jukebox in the café and is upset when no one seems to notice the music playing in the background. Instead of remaining at the café, Cléo goes to a sculpting studio to visit her old friend, Dorothée, who is modelling nude for an artist. Once she's finished, Dorothée claims that her body makes her happy, not proud, and Dorothée drives Cléo to her home. Cléo tells her friend that she is dying of cancer. Dorothée returns the car to her lover, a projectionist, and they watch a silent movie from the projection booth, which jokingly shows a woman dying. Leaving the cinema, Cléo accidentally breaks a mirror, which she claims is a bad omen. Cléo and Dorothée then take a taxi, and pass a crime scene where a man was killed. Dorothée tells her that the broken mirror was meant for that man, not Cléo.

Having dropped Dorothée off at her apartment, Cléo has the taxi driver take her to Parc Montsouris. By a bridge on a river, Cléo meets Antoine, a soldier on leave from the Algerian War. Antoine helps Cléo realize her selfishness, and asks her to accompany him to the train station to return to the war if he accompanies her to the hospital to get her test results. Before leaving, Antoine confides in Cléo about his thoughts on the war, and that in Algeria, they die for nothing, and that scares him. He also tells Cléo that girls always seem to be afraid to give themselves completely to someone and that they're afraid of losing something close to them, so they love by halves. Cléo realizes that that describes her perfectly. Antoine and Cléo go to the hospital by bus, and the doctor who tested Cléo for her possible cancer isn't in, despite the fact that he told her he'd be present at 7 pm that day. Cléo and Antoine sit on a bench outside, as Cléo is still determined that the doctor will be there. While Cléo has come to terms with her illness and is able to face the test results with courage thanks to Antoine's help, the doctor rolls by in his car and tells Cléo that she has cancer and will need to undergo two months of radiation therapy. Cléo says that her fear seems to be gone, and she seems happy, while Antoine starts crying. She tells him that they have plenty of time together before he leaves to go back to Algeria as a soldier. For the first time in at least two hours, Cléo seems to be happy as she looks at Antoine.[1]

Cast

- Corinne Marchand as Cléo

- José Luis de Vilallonga as José, Cléo's lover

- Loye Payen as Irma

- Dominique Davray as Angèle

- Serge Korber as Maurice

- Dorothée Blanck as Dorothée

- Raymond Cauchetier as Raoul

- Michel Legrand as Bob

- Antoine Bourseiller as Antoine

- Robert Postec as Doctor Valineau

- Jean Champion as the café owner

- Jean-Pierre Taste as the waiter at the café

- Renée Duchateau as the seller of hats

- Lucienne Marchand as the taxi driver

Themes

While the film takes place in France, away from the Algerian front, the influence of Algerian war for independence is still strong. The war greatly affected France during the 1950s and 1960s, where the demands for decolonization were the strongest.[4] The soldier who Cléo meets towards the end of the film, Antoine, is on temporary leave from fighting in Algeria. Antoine also builds on the theme of existentialism that the film conveys, with his claims that the people in Algeria are dying for nothing. There are also protests on the street that Cléo encounters while taking a taxi back to her home.[1]

Cléo from 5 to 7 embodies the stereotypes that men subject women to and their oppressiveness. Cléo commonly complains that no one takes her seriously since she's a woman, and that the men think that she's faking her illness for attention. She seems to go along with these stereotypes as well, as many women in France did, telling herself essentially that beauty is everything by saying "as long as I'm beautiful, I'm alive."[1]

Beginning in the 1940s, the French intellectual scene was dominated by existentialism, a movement in philosophy that would greatly influence art in France well into the 1960s.[5] Cléo from 5 to 7 is largely an existential film, as for the entirety of the film, Cléo struggles with her existence and the potential of facing her mortality. The impending results of her medical exam and the mere possibility that she may be diagnosed with cancer leaves Cléo open to an existential mind where she is aware of her own mortality. Further, upon meeting Antoine, the soldier talks about the deaths of the Algerian War, and that they are dying for nothing and without a purpose, further appealing to the existential philosophy.[1]

Critical reception

On review aggregation website Rotten Tomatoes, the film has an approval rating of 96%, based on 27 reviews, with an average rating of 8.68/10. The website's critical consensus reads, "Cleo from 5 to 7 represents a beautifully filmed highlight of the French New Wave that encapsulates the appeal of the era while departing from its narrative conventions."[6]

In 2019, the BBC polled 368 film experts from 84 countries to name the 100 greatest films directed by women.[7] The film was voted the second greatest film directed by a woman.[7]

References

- ^ a b c d e "Cleo from 5 to 7". unifrance.org. Retrieved 2014-03-17.

- ^ "Festival de Cannes: Cléo from 5 to 7". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 2009-02-22.

- ^ TCM.com

- ^ Hunt, Michael H. (2014). World transformed, 1945 to the present. [S.l.]: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199372348.

- ^ Baert, Patrick (2011). "The sudden rise of French existentialism: a case-study in the sociology of intellectual life". Theory and Society. 40 (6): 619–644. doi:10.1007/s11186-011-9154-4. JSTOR 41475713. S2CID 144665348.

- ^ "Cleo From 5 to 7 (1961)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved November 17, 2020.

- ^ a b "The 100 greatest films directed by women". BBC Culture. Retrieved January 15, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link)

Further reading

- Bradshaw, Peter (April 29, 2010). "Cléo from 5 to 7". The Guardian. Retrieved March 17, 2018.

- Martin, Adrian (January 21, 2008). "Cléo from 5 to 7: Passionate Time". The Criterion Collection. Retrieved March 17, 2018.

- Mouton, Janice (Winter 2001). "From Feminine Masquerade to Flâneuse: Agnès Varda's Cléo in the City". Cinema Journal. 40 (2): 3–16. doi:10.1353/cj.2001.0004. JSTOR 1225840.

External links

- Cléo from 5 to 7 at IMDb

- Cleo from 5 to 7 at AllMovie

- Cléo from 5 to 7 an essay by Molly Haskell at the Criterion Collection