Report of 1800

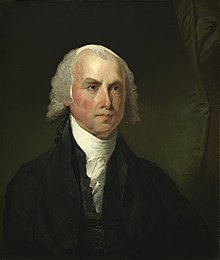

The Report of 1800 was a resolution drafted by James Madison arguing for the sovereignty of the individual states under the United States Constitution and against the Alien and Sedition Acts.[1] Adopted by the Virginia General Assembly in January 1800, the Report amends arguments from the 1798 Virginia Resolutions and attempts to resolve contemporary criticisms against the Resolutions. The Report was the last important explication of the Constitution produced before the 1817 Bonus Bill veto message by Madison, who has come to be regarded as the "Father of the Constitution."[2]

The arguments made in the Resolutions and the Report were later used frequently during the nullification crisis of 1832, when South Carolina declared federal tariffs to be unconstitutional and void within the state. Madison rejected the concept of nullification and the notion that his arguments supported such a practice. Whether Madison's theory of Republicanism really supported the nullification movement, and more broadly whether the ideas he expressed between 1798 and 1800 are consistent with his work before and after this period, are the main questions surrounding the Report in the modern literature.

Background

Madison, a member of the Democratic-Republican Party, was elected to the Democratic-Republican-dominated Virginia General Assembly from Orange County in 1799. A major item on his agenda was the defense of the General Assembly's 1798 Virginia Resolutions, of which Madison had been the draftsman.[3] The Resolutions, usually discussed together with Thomas Jefferson's contemporaneous Kentucky Resolutions, were a response to various perceived outrages perpetrated by the Federalist-dominated national government. The most significant of these were the Alien and Sedition Acts, four laws that allowed the President to deport aliens at will, required a longer period of residence before aliens could become citizens, and made it a crime to publish malicious or defamatory material against the government or its officials. Democratic-Republicans were outraged by the legislation, and Madison and Jefferson drafted the highly critical Resolutions adopted in response by the Virginia and Kentucky state legislatures.[citation needed]

The Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions had in the year since publication received highly critical replies from state legislatures. Seven states formally responded to Virginia and Kentucky by rejecting the Resolutions[4] and three other states passed resolutions expressing disapproval,[5] with the other four states taking no action. No other state endorsed the Resolutions. The reason for the criticism was that the General Assembly, led in the effort by state-sovereignty advocate John Taylor of Caroline, had put a state-sovereignty spin on the Virginia Resolutions of 1798 despite Madison's hopes. These replies contended that the Supreme Court of the United States had the ultimate responsibility for deciding whether federal laws were constitutional, and that the Alien and Sedition Acts were constitutional and necessary.[6] The Federalists accused the Democratic-Republicans of seeking disunion, even contemplating violence.[7] At the time, some leading Virginia Democratic-Republican figures such as Rep. William Branch Giles (in public) and Taylor (in private) actually were contemplating disunion, and the Virginia General Assembly chose this juncture for finally constructing a new state armory in Richmond, so there was some truth to the charge.[citation needed]

Jefferson, the leader of the Democratic-Republican Party and then–Vice President, wrote to Madison in August 1799 outlining a campaign to strengthen public support for the principles expressed in the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions of 1798 (commonly referred to as "the principles of '98"):

That the principles already advanced by Virginia & Kentucky are not to be yielded in silence, I presume we all agree. I should propose a declaration of Resolution by their legislatures on this plan. 1st. Answer the reasonings of such of the states as have ventured in the field of reason, & that of the Committee of Congress. ... 2. Make a firm protestation against the principle & the precedent; and a reservation of the rights resulting to us from these palpable violations of the constitutional compact by the Federal government, ... 3. Express in affectionate and conciliatory language our warm attachment to union with our sister-states, and to the instrument & principles by which we are united; ... fully confident that the good sense of the American people and their attachment to rally with us round the true principle of our federal compact. But determined, were we to be disappointed in this, to sever ourselves from that union we so much value, rather than give up the rights of self government which we have reserved, & in which alone we see liberty, safety & happiness.[8]

In response to this letter, Madison visited Jefferson at Monticello during the first week of September.[9] Their discussion was important in that it persuaded Jefferson to depart from his radical stance on dissociation from the Union, which is expressed at the end of the excerpt above. At the very least, Virginia or Kentucky taking such a stance publicly would have justified the Federalist attacks against the secessionist tendencies of the Democratic-Republicans. Madison won over Jefferson, who shortly thereafter wrote to Wilson Cary Nicholas that: "From [this position] I retreat readily, not only in deference to [Madison's] judgment but because as we should never think of separation but for repeated and enormous violations, so these, when they occur, will be cause enough of themselves."[10] Adrienne Koch and Harry Ammon, examining Jefferson's later writing, conclude that Madison had a significant role "in softening Jefferson's more extreme views."[11]

Jefferson hoped for further involvement with the production of the Report and planned to visit Madison at Montpelier on his way to Philadelphia, the national capital, for the winter session of the United States Congress. However, James Monroe, who would become Governor of Virginia before the end of the year, visited Jefferson at Monticello and cautioned him against meeting with Madison, since another meeting between two of the most important Democratic-Republican leaders would provoke significant public comment.[12] The task of writing the Virginia Report was left solely to Madison. Jefferson underlined the importance of this work in a November 26 letter to Madison in which he identified "protestations against violations of the true principles of our constitution" as one of the four primary elements of the Democratic-Republican Party plan.[13]

Production and passage

The Assembly session began in early December. Once at Richmond, Madison began drafting the Report,[14] though he was delayed by a weeklong battle with dysentery.[15] On December 23, Madison moved for the creation of a special seven-member committee with himself as chairman to respond to "certain answers from several of the states, relative to the communications made by the Virginia legislature at their last session." The committee members were Madison, John Taylor, William Branch Giles, George Keith Taylor, John Wise, John Mercer, and William Daniel.[16] The next day, Christmas Eve, the committee produced a first version of the Report.[17] The measure came before the House of Delegates, the lower house of the General Assembly, on January 2.

Though certain to pass due to the Democratic-Republican majority, which had recently been solidified by the election of a Democratic-Republican clerk and speaker of the House, the Report was debated for five days. The main point of contention was the meaning of the third of the Virginia Resolutions:

this Assembly doth explicitly and peremptorily declare, that it views the powers of the federal government, as resulting from the compact to which the states are parties; ... and that in case of a deliberate, palpable, and dangerous exercise of other powers not granted by said compact, the states who are parties thereto have the right ... to interpose for arresting the progress of the evil ... the authorities, rights, and liberties appertaining to them.[18]

This resolution had been the principal target of the Federalist attack on the Resolutions.[19] Particularly at issue was the sense in which the states were parties to the federal compact. The Report was ultimately amended to provide greater clarity on this issue by emphasizing that when the Virginians claimed that the "states" were parties to the federal Constitution, the referent of the word "state" was the sovereign people of the particular state. Thus, to say that "the state of Virginia ratified the Constitution" was to say that the sovereign people of Virginia ratified the Constitution. The amended Report passed the House of Delegates on January 7 by a margin of 60 to 40. At some point in the next two weeks, it passed the Senate by a margin of 15 to 6.[20]

The Report was received warmly by Virginia Democratic-Republicans. The General Assembly arranged for five thousand copies to be printed and distributed in the state, but there was not much public response to the Report, and it appears to have had relatively little impact on the presidential election of 1800 (which was, nevertheless, a major victory for the Democratic-Republicans and a repudiation of Federalist policies). Parties outside Virginia seemed uninterested in the rehashing of the 1798 Resolutions, and in other states there was very little public comment. Jefferson eagerly sought copies for distribution to Democratic-Republican members of Congress departing for their home states, and when they failed to arrive he entreated Monroe for at least one copy that he could reproduce. Despite Jefferson's approval of and attempt to distribute Madison's work, the national reaction was tepid.[21] Though it had little impact on the immediate election, Madison's Report clarified the legal argument against the Acts and for states' rights in general, particularly in its advancement of the Tenth Amendment rather than the Ninth as the main bulwark against federal encroachment on state autonomy.[22]

Argument

The general purpose of the Report was the affirmation and expansion of the principles expressed in the Virginia Resolutions. The first major goal of the Resolutions was to bring about the repeal of the Alien and Sedition Acts by generating public opposition that would be expressed through the state legislatures. Madison sought to accomplish this by demonstrating conclusively that the Acts violated the constitution. Laying into the Acts in his Report, Madison described many breaches of constitutional limits. The Alien Act granted the President the unenumerated power of deporting friendly aliens.[23] Contrary to the Sedition Act, the federal government had no power to protect officials from dissent or libelous attack, beyond the protection it accorded to every citizen; indeed, such special intervention against the press was "expressly forbidden by a declaratory amendment to the constitution."[24] As well, Madison attacked Federalist carriage laws and bank laws as unconstitutional.[citation needed]

To remedy the defects revealed by the passage of the Alien and Sedition Acts, Madison called for citizens to have an absolute right to free speech. Madison writes that the ability to prosecute speech amounts to "a protection of those who administer the government, if they should at any time deserve the contempt or hatred of the people, against being exposed to it."[25] Freedom of the press was necessary, because "chequered as it is with abuses, the world is indebted to the press for all the triumphs which have been gained by reason and humanity over error and oppression."[26] The Report supported a strict interpretation of the First Amendment.[citation needed] While the Federalists interpreted the amendment as limiting the power of Congress over the press, but implying that such power existed, Madison argued that the First Amendment wholly prohibited Congress from any interference with the press.

More generally, the Report made the argument in favor of the sovereignty of the individual states, for which it is best known. The basic message was that the states were the ultimate parties constituting the federal compact, and that therefore the individual states were ultimate arbiters of whether the compact had been broken by the usurpation of power. This doctrine is known as the compact theory. It was the presence of this argument in the Resolutions that had allowed the Federalists to paint the Democratic-Republicans as leaning toward secession; in the amended Report the line is moderated, with an emphasis that it is the states as political societies of the people (and therefore, one reads in, not the state legislatures alone) which possess this power. Either formulation would help the Democratic-Republican cause by refuting the finality of any constitutional interpretation advanced by the Congress and federal judiciary, both of which were dominated by Federalists.[citation needed]

In defense of Virginia Democratic-Republicans and the Resolutions, Madison emphasized that even if one disagreed with the compact theory, the Virginia Resolutions and the Report of 1800 themselves were simply protests, which states were surely entitled to produce. Madison indicated that a declaration of unconstitutionality would be an expression of opinion, with no legal force.[27] The purpose of such a declaration, said Madison, was to mobilize public opinion. Madison indicated that the power to make binding constitutional determinations remained in the federal courts:

It has been said, that it belongs to the judiciary of the United States, and not the state legislatures, to declare the meaning of the Federal Constitution. ... [T]he declarations of [the citizens or the state legislature], whether affirming or denying the constitutionality of measures of the Federal Government ... are expressions of opinion, unaccompanied with any other effect than what they may produce on opinion, by exciting reflection. The expositions of the judiciary, on the other hand, are carried into immediate effect by force. The former may lead to a change in the legislative expression of the general will; possibly to a change in the opinion of the judiciary; the latter enforces the general will, whilst that will and that opinion continue unchanged.

Madison argued that a state, after declaring a federal law unconstitutional, could take action by communicating with other states, attempting to enlist their support, petitioning Congress to repeal the law in question, introducing amendments to the Constitution in Congress, or calling a constitutional convention. Madison did not assert that the states could legally nullify an objectionable federal law or that they could declare it void and unenforceable. By eschewing direct action in favor of influencing popular opinion, Madison tried to make clear that the Democratic-Republicans were not moving toward disunion.[citation needed]

Analysis

The Report was regarded in the early 19th century as among the more important expressions of Democratic-Republican principles. Spencer Roane described it as "the Magna Charta on which the republicans settled down, after the great struggle in the year 1799."[28] Henry Clay said on the floor of the House of Representatives that it was from the Report of 1800, above other documents, that he had developed his own theories on constitutional interpretation.[29] H. Jefferson Powell, a modern jurist, identifies three persistent themes of Democratic-Republican constitutionalism which emerged from the Resolutions and the Report: (1) a textual approach to the Constitution, (2) the compact theory, and (3) that caution, not trust, should characterize our approach to those who hold political power.[30]

In more recent years, the main practical interest in the Report has been its absolutist understanding of the First Amendment.[citation needed] Multiple Supreme Court decisions have cited the case as evidence of the Framers' ideas on free speech. In the 1957 Roth v. United States opinion by William Brennan, Madison's Report is cited as evidence that "the fundamental freedoms of speech and press have contributed greatly to the development and well-being of our free society and are indispensable to its continued growth."[31] Other cases to cite the Report for a similar purpose include Thornhill v. Alabama (1940)[32] and Nixon v. Shrink Missouri Government PAC (2000).[33]

In modern scholarship outside the legal arena the Report is mostly studied for its discussion of states' rights with regard to federalism and republicanism.[citation needed] According to Kevin Gutzman, the Report, together with the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions, forms a foundation for the "radical southern states' rights tradition."[34] However, Madison rebuffed charges that his writings supported the constitutional interpretation advanced by pro-nullification Southerners. The Report of 1800, Madison argued, did not say the government was a compact of the individual states, as the pro-nullification elements suggested. Rather the Report of 1800 described a compact of "the people in each of the States, acting in their highest sovereign capacity."[35] The state governments themselves, no less than the federal judiciary, possess only delegated power and therefore cannot decide questions of fundamental importance. Madison thought the Resolutions and Report were consistent with this principle while the Ordinance of Nullification was not.[36]

Notes

- ^ The Report is also known as the Virginia Report of 1800, the Report of 1799, Madison's Report or the Report on the Alien and Sedition Acts.

- ^ See, e.g., Brant's subtitle "Father of the Constitution."

- ^ Madison initially decided to run for office mainly to counteract the strength of prominent Federalist Patrick Henry, who was set to be elected to the House. However, Henry died over the summer, leaving the Democratic-Republicans free to pursue their plans with no substantial opposition. Madison, 303.

- ^ The seven states that transmitted formal rejections were Delaware, Massachusetts, New York, Connecticut, Rhode Island, New Hampshire, and Vermont. See Elliot, Jonathan (1907) [1836]. . Vol. 4 (expanded 2nd ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott. pp. 538–539. ISBN 0-8337-1038-9.

- ^ Maryland, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey passed resolutions that disapproved the Kentucky and Virginia resolutions, but these states did not transmit formal responses to Kentucky and Virginia. Anderson, Frank Maloy (1899). . American Historical Review. 5 (1): 45–63, 225–244. doi:10.2307/1832959. JSTOR 1832959.

- ^ Madison, 303. At least six states responded to the Virginia and Kentucky resolutions by stating that the power to declare a law unconstitutional rested in the federal judiciary, not the states. For example, Vermont's resolution stated: "It belongs not to state legislatures to decide on the constitutionality of laws made by the general government; this power being exclusively vested in the judiciary courts of the Union." Elliot, Jonathan (1907) [1836]. . . Vol. 4 (expanded 2nd ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott. pp. 538–539. ISBN 0-8337-1038-9.. The other states taking the position that the constitutionality of federal laws is a question for the federal courts, not the states, were New York, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, New Hampshire, and Pennsylvania. The Governor of Delaware also took this position. Anderson, Frank Maloy (1899). . American Historical Review. 5 (1): 45–63, 225–244. doi:10.2307/1832959. JSTOR 1832959.

- ^ Koch and Ammon, 163.

- ^ Letter from Jefferson to Madison of August 23, 1799. Quoted in Koch and Ammon, 165–166.

- ^ Madison, 304.

- ^ Letter from Jefferson to W.C. Nicholas of September 5, 1799, quoted in Brant, 467.

- ^ Koch and Ammon, 167.

- ^ Koch and Ammon, 169–170.

- ^ Letter from Jefferson to Madison of November 26, 1799, quoted in Koch and Ammon, 170.

- ^ Madison, 303.

- ^ Brant, 467.

- ^ Madison, 296, 304.

- ^ Neither this version nor any of Madison's drafts survive.

- ^ Madison, 189. The Virginia Resolutions emerged from the House of Delegates on December 21, 1798.

- ^ Gutzman, 582.

- ^ Madison, 305.

- ^ Koch and Ammon, 171; Madison, 306.

- ^ Lash, 183–184.

- ^ The Democratic-Republicans did not oppose the Alien Enemies Act, which permitted the deportation of enemy aliens, and is still in force.

- ^ Madison, 341.

- ^ Madison, 344.

- ^ Madison, 338.

- ^ Madison, 348. It is worth noting that at this period Americans still followed a British understanding in which laws could be "unconstitutional" without being illegal. Virginia's declaration that the Alien and Sedition Acts were unconstitutional did not necessarily signify a belief that the Acts were without effect.

- ^ Powell, 695.

- ^ Powell, 696.

- ^ Powell, 705–706.

- ^ Roth v. United States, 354 U.S. 476 (1957).

- ^ Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U.S. 88 (1940).

- ^ Nixon v. Shrink Missouri Government PAC, 528 U.S. 377 (2000).

- ^ Gutzman, 571.

- ^ Gibson, 319. The quote is from Drew McCoy, The Last of the Fathers: James Madison & the Republican Legacy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), p. 134.

- ^ Yarbrough, 42–43.

References

- Brant, Irving. James Madison: Father of the Constitution, 1787–1800. Indianapolis: The Bobbs-Merrill Company, Inc., 1950. See especially pp. 466–471, which covers the period examined here; the book is the third volume of six in Brant's biography of Madison, which is the most detailed scholarly biography thus far published.

- Gibson, Alan. "The Madisonian Madison and the Question of Consistency: The Significance and Challenge of Recent Research." Review of Politics 64 (2002): 311–338.

- Gutzman, Kevin R. "A Troublesome Legacy: James Madison and 'The Principles of '98'." Journal of the Early Republic 15 (1995): 569–589.

- Gutzman, K[evin] R. Constantine. "The Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions Reconsidered: 'An Appeal to the Real Laws of Our Country'." Journal of Southern History 66 (2000): 473–496. doi:10.2307/2587865

- Gutzman, Kevin R. C., Virginia's American Revolution: From Dominion to Republic, 1776-1840. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books, 2007.

- Koch, Adrienne and Harry Ammon. "The Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions: An Episode in Jefferson's and Madison's Defense of Civil Liberties." William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd series, 5 (1948): 145–176.

- Lash, Kurt T. "James Madison's Celebrated Report of 1800: The Transformation of the Tenth Amendment." George Washington Law Review 74 (2006): 165–200.

- Madison, James. The Papers of James Madison. Vol. 17: March 1797 through March 1801. Edited by David B. Mattern. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1991. The Report appears in pp. 303–351. The editorial note on pp. 303–306 is used heavily in this article.

- McCoy, Drew. The Last of the Fathers: James Madison & the Republican Legacy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

- Nixon v. Shrink Missouri Government PAC, 528 U.S. 377 (2000).

- Powell, H. Jefferson. "The Principles of '98: An Essay in Historical Retrieval." Virginia Law Review 80 (1994): 689–743.

- Roth v. United States, 354 U.S. 476 (1957).

- Thornhill v. State of Alabama, 310 U.S. 88 (1940).

- Yarbrough, Jean. "Rethinking 'The Federalist's View of Federalism'." Publius 15 (1985): 31–53.

External links