Concubinage in the Muslim world

Relationships (Outline) |

|---|

Concubinage in the Muslim World was typically the practice of men, married or otherwise, entering into sexual relations with a female slave (though in some eras free concubines) as part of a formalised type of arrangement broadly, though not always, sanctioned by Islamic law. These practices drew upon a cultural backdrop of the frequent use of concubinage for reproduction in many Middle Eastern societies.[1] For instance, the practice of a barren wife giving her husband a slave as a concubine is recorded in the Code of Hammurabi and the Bible, where Abraham takes Hagar as pilegesh.[1] Such relationships were also common in pre-Islamic Arabia and other pre-existing cultures of the wider region.[2] Islam brought its own legal restrictions to the practice. In the Medieval Muslim Arab world, the term surriyya came to be used to refer to female slaves (jariya) that were engaged in sexual intercourse in addition to domestic duties or other services of functions.

While in medieval Europe, children born outside of marriage would have been considered bastards, the children of concubinage relationships in the Middle East were often regarded as legitimate, and this perspective was largely carried over into the Islamic period.[1] Such concubinage was widely practiced in the pre-modern Muslim world, especially in some of the later Islamicate periods. For example, many of the rulers of the Abbasid caliphate and the Ottoman Empire were born out of such relationships.[3] As in Asia, many powerful men in the Middle East kept as many concubines as they could financially support.[4] Some royal households had thousands of concubines. In such cases, concubinage served as a status symbol and for the production of sons.[1] In societies that accepted polygyny, there were advantages to having a concubine over a mistress, as children from a concubine were legitimate, while children from a mistress would still be considered "bastards".[5]

Characteristics

Attempts to categorize the various patterns of concubinage often define Islamic practice as a distinct variant. In one reading, there are three cultural patterns of concubinage: Asian, Islamic and European.[6] Concubinage has also been categorised in terms of form and function, which in the Islamic world varied between times and places. The International Encyclopedia of Anthropology gives four distinct forms of concubinage,[7] three of which are potentially applicable to the Muslim Word: elite concubinage, related primarily to social status, which in the Muslim world resembled slavery; royal concubinage, where politics were connected to reproduction and concubines became consorts to the ruler, fostered diplomatic relations, and perpetuated the royal bloodline, including in the Ottoman empire; and concubinage that could also function as a form of sexual enslavement of women in a patriarchal system, where the children of the concubine could become permanently inferior to the children of the wife. This was more common in Asia, and Islamicate examples include Mughal India.[7]

In slave-owning societies, most concubines were slaves, but not all.[4] Many societies automatically freed the concubine after she had a child. According to one study, this was the case in about one-third of slave-holding societies, the most prominent being case of the Muslim world.[a] In Islamic culture, a slave who bore a child to a free man was known as an umm al-walad, could not be sold, and, in most circumstances, at her owner's death, was freed.[9] The children of concubines were generally declared as legitimate.[2] Among societies that did not legally require the manumission of concubines, it was usually done anyway.[8] Islam additionally encouraged manumission.

The concubine of a king could meanwhile also achieve considerable power, especially if her son also became a monarch.[4] There is also evidence that concubines generally had a higher rank than female slaves. Abu Hanifa and others argued for modesty-like practices for the concubine, recommending that the concubine be established in the home and their chastity be protected and not to misuse them for sale or sharing with friends or kin.[2] While scholars exhorted masters to treat their slaves equally, a master was allowed to show favoritism towards a concubine.[2] Some scholars recommended holding a wedding banquet (walima) to celebrate the concubinage relationship, but this was not required by the teachings of Islam and was rather the opinions of certain scholars.[2]

The expansion of various Muslim dynasties resulted in acquisitions of concubines, through purchase, gifts from other rulers, and captives of war. To have a large number of concubines became a symbol of status.[3] While Muslim soldiers in the early Islamic conquests were given female captives as a reward for military participation, in later they were frequently purhcased and men were permitted to have as many concubines as they could afford. As the slaves for pleasure were typically more expensive, they were typically a privilege for elite men.[10] Most Islamic schools of thought restricted concubinage to a relationship where the female slave was required to be monogamous to her master.[11]

Almost all Abbasid caliphs were born to concubines and several Twelver Shia imams were also born to concubines.[12] Similarly, the sultans of the Ottoman empire were often the son of a concubine.[3] As a result concubines came to exercise a degree of influence over Ottoman politics.[3] Ottoman sultans appeared to have preferred concubinage to marriage,[13] and for a time all royal children were born of concubines.[14] The consorts of Ottoman sultans were often neither Turkish, nor Muslim by birth.[15] Leslie Peirce argues that this was because a concubine would not have the political leverage that would be possessed by a princess or a daughter of the local elite.[14] Ottoman sultans also appeared to have only one son with each concubine; that is once a concubine gave birth to a son, the sultan would no longer have intercourse with her. This limited the power of each son.[16] Even so, many concubines developed social networks, and accumulated personal wealth, both of which allowed them to rise in terms of social status.[12] The practice declined with the abolition of slavery, starting in the 19th century.[3]

Islamic views

Islamic law and Sunni ulama historically recognised several categories of concubines.[17] The term surriya was used for female slaves with whom masters enjoyed sexual relations and has been widely translated in Western scholarship as "concubine"[18][19][20] or "slave concubine".[18] In other texts they are referred to as "slaves for pleasure" or "slave-girls for sexual intercourse".[21] Islamic law obliged slave owners to provide their female slaves with food, clothing, shelter, and protection from sexual exploitation by anyone who was not their owner.[22] However, it was not a secure status as the concubine could be traded as long as the master had not impregnated her.[23] While enslaved concubines could rise to positions of influence, these position did not legally protect them from forced labour, forced marriage and sex, and even elite slaves were still traded as chattel.[22] If she bore her master a child and if he accepted paternity she could obtain the position of an Umm walad. Separately, if someone bought a woman with child, they could not be separated until, according to Ibn Abi Zayd, the child was six years old.[24]

Practice in the Middle East

Early Islamic and Umayyad periods

Historical data from the pre-Islamic and early Islamic periods in Arabia data shows that there was a massive increase in the number of children born to concubines with the emergence of Islam.[25] An analysis of the information found that no children were born from concubines before the generation of Muhammad's grandfather. There were a few cases of children being born from concubines before Muhammad but they were only in his father's and grandfather's generation. The analysis of the data thus showed that concubinage was not common in the western Arabian Peninsula immediately before the time of Muhammad,[26] but increased after the early Muslim conquests due to the wealth and power they brought to the Quraysh tribes.[b]

Concubinage expanded significantly in the Umayyad period, driven by the dynastic desire for sons rather than sanctions for it in the Qur'an, Hadith or Sunnah.[28] Concubinage was allowed among the Sassanian elites and the Mazdeans at the time, but the children from such unions were not necessarily regarded as legitimate.[29] The position of Jewish communities is unclear although slave concubinage is mentioned in Biblical texts. Apparently, the practice had declined long before Muhammad. Some Jewish scholars during Islamic rule would forbid Jews from having sex with their female slaves.[29] Leo III in his letter to Umar II accused Muslims of "debauchery" with their concubines who they would sell "like dumb cattle" after having tired of using them.[29] One Umayyad ruler, Abd al-Rahman III, was known to have possessed more than 6,000 concubines.[30]

Abbasid Empire and successor states

The royals and nobles during the Abbasid Caliphate kept large numbers of concubines. The Caliph Harun al-Rashid possessed hundreds of concubines in his harem. The Caliph al-Mutawakkil was reported to have owned four thousand concubines.[30] Slaves for pleasure were costly and were a luxury for wealthy men, but women preferred that their husbands keep concubines instead of taking a second wife. This was because a co-wife represented a greater threat to their position. Owning many concubines was perhaps more common than having several wives.[31]

In Al-Andalus, the concubines of the Almoravid and Almohad Muslim elite were usually non-Muslim women from the Christian areas of the Iberian peninsula. Many of these had been captured in raids or wars and were then gifted to the elite Muslim soldiers as war booty or were sold as slaves in Muslim markets.[32] In Muslim society in general, monogamy was common because keeping multiple wives and concubines was not affordable for many households. The practice of keeping concubines was common in the Muslim upper class. Muslim rulers preferred having children with concubines because it helped them avoid the social and political complexities arising from marriage and kept their lineages separate from the other lineages in society.[32] In Mamluk Egypt, the Mamluk governor of Baghdad, Umar Pasha, died childless because his wife prevented him from having a concubine.[33]

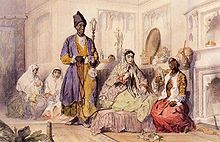

Ottoman Empire

From the late 1300s, Ottoman sultans would only permit heirs born from concubines to inherit their throne. Each concubine was only permitted to have one son. Once a concubine would bear a son she would spend the rest of her life plotting in favour of her son. If her son was to successfully become the next Sultan, she would become an unquestionable ruler. After the 1450s the Sultans stopped marrying altogether. Because of this there was great surprise when Sultan Sulayman fell in love with his concubine and married her.[30] One particularly prominent concubine was Roxelana, who rose from being a Christian slave-girl into the chief advisor of her husband, Sultan Suleyman of the Ottoman Empire. There are also several other accounts of such women of humble birth who associated with powerful Muslim men, many of them written up by foreign diplomats who wrote with disappointment about apostate women who wielded political influence over their masters-turned-husbands. Christian women who converted to Islam and then became politically assertive were regarded with particular disfavour in Europe.[34]

The Ottoman rulers kept up the practice of maintaining an Imperial harem into the 1890s.[35] Most slaves in the Ottoman harem comprised women who had been captured in battle, abducted during raids by the Tatars or seized by maritime pirates,[36] including muslim Circassian women and girls.[37] Ambitious families associated with the palace would also frequently offer their daughters up as concubines.[35] Research into Ottoman records nevertheless show that polygamy was absent or rare quite uncommon outside the elite by the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries,[38] while monogamy was a feature of the "progressive middle class".[39]

Writing in the early 18th century, one visitor noted that from among the Ottoman courtiers, only the imperial treasurer kept female slaves for sex and others thought of him as a lustful person.[40] Edward Lane, who visited Egypt in the 1830s, noted that very few Egyptian men were polygamous and most of the men with only one wife did not keep concubines, usually for the sake of domestic peace. However, some kept Abyssinian slaves who were less costly than maintaining a wife. While white slave-girls would be in the keep of wealthy Turks, the concubines kept by upper and middle class Egyptians were usually Abyssinians.[41] Concubinage was also practiced Jewish households in the Ottoman empire, where it resembled the practice among the Muslim households, despite Jewish religious prohibitions of the practice.[42]

Imperial Harem

Very little is actually known about the Imperial Harem, and much of what is thought to be known is actually conjecture and imagination.[45] There are two main reasons for the lack of accurate accounts on this subject. The first was the barrier imposed by the people of the Ottoman society – the Ottoman people did not know much about the machinations of the Imperial Harem themselves, due to it being physically impenetrable, and because the silence of insiders was enforced.[45] The second was that any accounts from this period were from European travelers, who were both not privy to the information, and also inherently presented a Western bias, with scandalous stories of the Imperial Harem and the sexual practices of the sultans being particularly popular, even if they were not true.[45] Accounts from the seventeenth century drew from both a newer, seventeenth century trend as well as a more traditional style of history-telling; they presented the appearance of debunking previous accounts and exposing new truths, while proceeding to propagate old tales as well as create new ones.[45]

The concubines of the Ottoman Sultan consisted chiefly of purchased slaves. The Sultan's concubines were generally of Christian origin (usually European, Circassian, or Georgian). Most of the elites of the Harem Ottoman Empire included many women, such as the sultan's mother, preferred concubines, royal concubines, children (princes/princess), and administrative personnel. The administrative personnel of the palace were made up of many high-ranking women officers, they were responsible for the training of Jawaris for domestic chores.[45] The mother of a Sultan, though technically a slave, received the extremely powerful title of Valide Sultan which raised her to the status of a ruler of the Empire (see Sultanate of Women). The mother of the Sultan played a substantial role in decision-making for the Imperial Harem. One notable example was Kösem Sultan, daughter of a Greek Christian priest, who dominated the Ottoman Empire during the early decades of the 17th century.[46] Roxelana (also known as Hürrem Sultan), another notable example, was the favorite wife of Suleiman the Magnificent.

The Ottoman Imperial Harem was similar to a training institution for concubines, and served as a way to get closer to the Ottoman elite.[45] Women from lower-class families had especially good opportunities for social mobility in the imperial harem because they could be trained to be concubines for high-ranking military officials.[45] Concubines had an chance for even greater power in Ottoman society if they became favorites of the sultan.[45] The sultan would keep a large number of girls as his concubines in the New Palace, which as a result became known as "the palace of the girls" in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.[45]

Mughal India

It has been reported that the Mughal Emporer Akbar had a harem of at least 5,000 women and that Aurangzeb's harem was even larger, and that the nobles in India could possess as many concubines as they wanted.[47] Ismail Quli Khan, a Mughal noble, alledgely possessed 1,200 girls. Another nobleman, Said, was said to have had so many wives and concubines that he fathered 60 sons in just four years.[48] Francisco Pelseart described that noblemen would visit a different wife each night, who would welcome him along with the slave girls. If he felt attracted to any slave-girl he would call her to him for his enjoyment while the wife would not dare to show her anger. The wife would punish the slave-girl later.[49]

Lower class Muslims were generally monogamous. Since they hardly had any rivals, women of the lower and middle class sections of society fared better than upper-class women who had to contend with their husbands' other wives, slave-girls and concubines.[50] Shireen Moosvi has discovered Muslim marriage contracts from Surat, dating back to the 1650s. One stipulation in these marriage contracts was that the husband was not to marry a second wife. Another stipulation was that the husband would not take a slave girl. These stipulations were common among middle-class Muslims in Surat. If the husband took a second wife the first wife would gain an automatic right of divorce, thus indicating the preference for monogamy among the merchants of Surat. If the husband took a slave-girl the wife could sell, free or give away that slave-girl, thereby separating the female slave from her husband.[51]

There is no evidence that concubinage was practiced in Kashmir where, unlike the rest of the medieval Muslim world, slavery was abhorred and not widespread. Except for the Sultans, there is no evidence that the Kashmiri nobility or merchants kept slaves.[52] In medieval Punjab the Muslim peasants, artisans, small tradesmen, shopkeepers, clerks and minor officials could not afford concubines or slaves,[53] but the Muslim nobility of medieval Punjab, such as the Khans and Maliks, kept concubines and slaves. Female slaves were used for concubinage in many wealthy Muslim households of Punjab.[54]

Colonial court cases from 19th century Punjab show that the courts recognised the legitimate status of children born to Muslim zamindars (landlords) from their concubines.[55] The Muslim rulers of Indian princely states, such as the Nawab of Junagadh, also kept slave girls.[56] The Nawab of Bahawalpur, according to a Pakistani journalist, kept 390 concubines. He only had sex with most of them once.[57] Marathas captured during their wars with the Mughals had been given to the soldiers of the Mughal Army from the Baloch Bugti tribe. The descendants of these captives became known as "Mrattas" and their women were traditionally used as concubines by the Bugtis. They became equal citizens of Pakistan in 1947.[58]

References

Notes

- ^ Many societies in addition to those advocating Islam automatically freed the concubine, especially after she had had a child. About a third of all non-Islamic societies fall into this category.[8]

- ^ The conquests, however, had consequences that ultimately upset the pre-Islamic system. As the Umayyad dynasty matured, certain families within the Quraysh became significantly wealthier and more powerful than tribes that had once been equal to them...In this new order, the Muslim elites turned to the cheapest, safest, and most loyal women available to them: cousins and concubines.[27]

Citations

- ^ a b c d Kushner 2008, p. 469

- ^ a b c d e Katz 1986

- ^ a b c d e Cortese & Calderini 2006

- ^ a b c Klein 2014, p. 122

- ^ Walthall 2008, p. 13.

- ^ Rodriguez 2011, p. 203.

- ^ a b The International Encyclopedia of Anthropology 1999.

- ^ a b Peterson 1982

- ^ Gordon & Hain 2017, p. 328.

- ^ Myrne 2019, p. 203.

- ^ Bloom & Blair 2002, p. 48.

- ^ a b Gordon 2017, p. 4–5

- ^ Peirce 1993, p. 30.

- ^ a b Peirce 1993, p. 39.

- ^ Peirce 1993, p. 37.

- ^ Peirce 1993, p. 42-43.

- ^ Clarence-Smith 2006, p. 22.

- ^ a b Brown 2019, p. 70.

- ^ Robinson 2017, p. 90.

- ^ Reda & Amin, p. 228.

- ^ Myrne 2019, pp. 196–197.

- ^ a b Myrne 2019, pp. 222–223.

- ^ Ali 2015, p. 50–51.

- ^ Bellagamba, Greene & Klein 2016, p. 24.

- ^ Robinson 2017, p. 11–12

- ^ Robinson 2017, p. 16–17.

- ^ Robinson 2017, p. 20–21

- ^ Robinson 2020, p. 107.

- ^ a b c Robinson 2020, p. 96–97.

- ^ a b c Clarence-Smith 2006, p. 89.

- ^ Myrne 2019, p. 206.

- ^ a b Bennison 2016, p. 155–156.

- ^ Clarence-Smith 2006, p. 81.

- ^ Foster 2009, p. 57–60

- ^ a b Rodriguez 2011, pp. 203–204.

- ^ Ard Boone 2018, p. 58.

- ^ Yelbasi 2019, p. 14.

- ^ Irwin 2010, p. 531.

- ^ Ahmed 1992, p. 107.

- ^ Kia 2011, p. 199.

- ^ Lewis 1992, p. 74.

- ^ Forster, 2009 & 30.

- ^ Smith 2008.

- ^ Peirce 1993, p. 59.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Peirce 1993

- ^ Winik 2007.

- ^ Bano 1999, p. 354–357.

- ^ Bano 1999, p. 361.

- ^ Lal 2005, p. 40.

- ^ Sharma 2016, p. 61.

- ^ Faroqhi 2019, p. 244.

- ^ Hasan 2005, p. 244.

- ^ Gandhi 2007, p. 19.

- ^ Grewal 1998, p. 11–12.

- ^ Tremlett 1869, pp. 244–.

- ^ Chattopadhyay 1959, p. 126.

- ^ Weiss 2004, p. 190.

- ^ Lieven 2012, p. 362.

Sources

- Ahmed, Leila (1992). Women and Gender in Islam: Historical Roots of a Modern Debate. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-05583-2.

- Ali, Kecia (2015). Sexual Ethics and Islam: Feminist Reflections on Qur'an, Hadith and Jurisprudence. Oneworld Publications. ISBN 978-1-78074-853-5.

- Bloom, Jonathan; Blair, Sheila (2002). Islam: A Thousand Years of Faith and Power. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09422-1.

- Ard Boone, Rebecca (2018). Real Lives in the Sixteenth Century: A Global Perspective. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-351-13533-7.

- Bano, Shadab (1999). "Marriage and Concubinage in the Mughal Imperial Family". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 60.

- Bellagamba, Alice; Greene, Sandra Elaine; Klein, Martin A. (2016). African Voices on Slavery and the Slave Trade. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-19961-2.

- Bennison, Amira K. (1 August 2016). Almoravid and Almohad Empires. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-4682-1.

- Brown, Jonathan A. C. (2019). Slavery and Islam. Simon & Schuster. p. 70.

- Chattopadhyay, Amal Kumar (1959). Slavery in India; with an introduction by Radha Kumud Mukherjee and with a foreword by Asim Kumar Datta. Nagarjun Press – via Internet Archive.

- Clarence-Smith, William Gervase (2006). Islam and the Abolition of Slavery. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195221510.

- Cortese, D.; Calderini, S. (2006). Women and the Fatimids in the World of slam. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 9780748626298.

- Faroqhi, Suraiya (8 August 2019). The Ottoman and Mughal Empires: Social History in the Early Modern World. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78831-873-0.

- Gordon, Matthew S. (2017). "Introduction". In Hain, Kathryn A (ed.). Concubines and Courtesans: Women and slavery in Islamic history. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oso/9780190622183.001.0001. ISBN 978-019062218-3.

- Gordon, Matthew S.; Hain, Kathryn A. (2017). Concubines and Courtesans: Women and slavery in Islamic history. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oso/9780190622183.001.0001. ISBN 978-019062218-3.}}

- Katz, Marion H. (1986). "Concubinage in Islamic law". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Vol. 3.

- Foster, William Henry (18 December 2009). Gender, Mastery and Slavery: From European to Atlantic World Frontiers. Macmillan International Higher Education. ISBN 978-0-230-31358-3.

- Gandhi, Surjit Singh (2007). History of Sikh Gurus Retold: 1469-1606 C.E. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. ISBN 978-81-269-0857-8.

- Grewal, J. S. (8 October 1998). The Sikhs of the Punjab. Cambridge University Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-521-63764-0 – via Internet Archive.

- Hasan, Mohibbul (2005). Kashmīr Under the Sultāns. Aakar Books. ISBN 978-81-87879-49-7.

- Irwin, Robert (4 November 2010). The New Cambridge History of Islam: Volume 4, Islamic Cultures and Societies to the End of the Eighteenth Century. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-316-18431-8.

- Kia, Mehrdad (2011). Daily Life in the Ottoman Empire. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-33692-8.

- Klein, Martin A. (2014). Historical Dictionary of Slavery and Abolition. ISBN 9780810875289.

- Lal, Ruby (22 September 2005). Domesticity and Power in the Early Mughal World. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85022-3.

- Lewis, Bernard (1992). Race and Slavery in the Middle East: An Historical Enquiry. Oxford University Press. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-19-505326-5 – via Internet Archive.

- Lieven, Anatol (6 March 2012). Pakistan: A Hard Country. PublicAffairs. ISBN 978-1-61039-162-7.

- Myrne, Pernilla (2019). "Slaves for Pleasure in Arabic Sex and Slave Purchase Manuals from the Tenth to the Twelfth Centuries". Journal of Global Slavery. 4 (2): 196–225. doi:10.1163/2405836X-00402004. S2CID 199952805.

- Peirce, Leslie P. (1993). The Imperial Harem Women and Sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire. Oxford University Press.

- Peterson, Orlando (1982). Slavery and Social Death. Harvard University Press. p. 230. ISBN 9780674810839.

- Reda, Nevin; Amin, Yasmin. Islamic Interpretive Tradition and Gender Justice. McGill-Queen's University Press.

- Robinson, Majied (2017). "Statistical Approaches to the Rise of Concubinage in Islam". In Gordon, Matthew S; Hain, Kathryn A (eds.). Concubines and Courtesans: Women and Slavery in Islamic History. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oso/9780190622183.003.0002. ISBN 978-019062218-3.

- Robinson, Majied (2020). Marriage in the Tribe of Muhammad: A Statistical Study of Early Arabic Genealogical Literature. De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-062423-6.

- Rodriguez, Junius P. (20 October 2011). Slavery in the Modern World: A History of Political, Social, and Economic Oppression [2 volumes]: A History of Political, Social, and Economic Oppression. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-788-3.

- Roy, Kaushik (15 October 2012). Hinduism and the Ethics of Warfare in South Asia: From Antiquity to the Present. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-01736-8.

- Kushner, Nina (2008). "Concubinage". In Smith, Bonnie G. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Women in World History. OUP. pp. 467–72. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195148909.001.0001. ISBN 9780195337860. Retrieved 2020-09-15.

- Sharma, Sudha (21 March 2016). The Status of Muslim Women in Medieval India. SAGE Publications. ISBN 978-93-5150-567-9.

- Smith, Samuel (25 September 2014). "International Coalition of Muslim Scholars Refute ISIS' Religious Arguments in Open Letter to al-Baghdadi". The Christian Post. Archived from the original on 2 April 2019. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- Tremlett, J. D. (1869). The Punjab Civil Code (part I) and Selected Acts, with a Commentary. Punjab Print Company.

- Weiss, Timothy F. (1 January 2004). Translating Orients: Between Ideology and Utopia. University of Toronto Press. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-8020-8958-8 – via Internet Archive.

- Walthall, Anne (2008). Servants of the Dynasty Palace Women in World History. University of California Press.

- Winik, Jay (2007). The Great Upheaval.

- Yelbasi, Caner (22 August 2019). The Circassians of Turkey: War, Violence and Nationalism from the Ottomans to Atatürk. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-83860-017-4.

Further reading

- Ali, Kecia (2017). "Concubinage and Consent". International Journal of Media Studies. 49 (1): 148–152. doi:10.1017/S0020743816001203. ISSN 0020-7438.

- Ben-Naeh, Yaron (2006). "Blond, Tall, with Honey-Colored Eyes: Jewish Ownership of Slaves in the Ottoman Empire". Jewish History. 20 (3): 315–332. doi:10.1007/s10835-006-9018-z. S2CID 159784262.