Oswald Boelcke

Oswald Boelcke | |

|---|---|

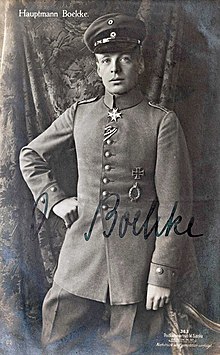

Oswald Boelcke in 1916 with the Pour le Mérite at his neck | |

| Born | 19 May 1891 Giebichenstein, Province of Saxony, Prussia; near Halle (Saale) |

| Died | 28 October 1916 (aged 25) near Bapaume, France |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | Telegraphen-Bataillon Nr. 3 (Telegraph Battalion No. 3); Luftstreitkräfte (Air Force) |

| Years of service | 1911–1916 |

| Rank | Hauptmann (Captain) |

| Unit | Feldflieger Abteilung 13 (Field Flyer Detachment 13) |

| Commands | Jagdstaffel 2 (Fighter Squadron 2) |

| Awards | Pour le Mérite, Royal House Order of Hohenzollern, Knight's Cross with Swords, Iron Cross, First and Second Class, Lifesaving Medal, Plus eight lesser decorations |

Oswald Boelcke PlM (German: [ˈbœlkə]; 19 May 1891 – 28 October 1916) was a World War I German professional soldier and pioneering flying ace credited with 40 credited aerial victories. Boelcke is honored as the father of the German fighter air force, as well as considered the "father of air combat". He was a very influential mentor, patrol leader, and tactician in the first years of air combat, 1915 and 1916.

Boelcke fulfilled his childhood dream of a military career by joining the Imperial German Army on 15 March 1911. He followed his interest in aviation, learning to fly as World War I began. After duty as an aerial observer during 1914, he became one of the original fighter pilots during mid-1915. Flying the first true fighters, Boelcke, Max Immelmann, and several other early aces began shooting down enemy airplanes. Boelcke and Immelmann were the first German fighter pilots awarded Prussia's highest honor, the Pour le Mérite. The German high command reassigned Boelcke after his 19th victory. During his forced grounding on staff duty, he helped transform the Army's Fliegertruppe (Flying Troop) air arm into the Luftstreitkräfte (Air Force). His innovative turn of mind codified his combat experiences into the first ever manual of fighter tactics distributed to an air force, the Dicta Boelcke. The Dicta promulgated axioms for individual pilot success, as well as a requirement for teamwork directed by a formation's leader. Present-day tactics manuals stem from the Dicta.

After an enforced holiday leave spent on a military inspection tour of Ottoman facilities, Boelcke was picked to lead one of Germany's first fighter squadrons, Jagdstaffel 2 (Fighter Squadron 2). Its pilots were handpicked by Boelcke and indoctrinated in his Dicta through extensive training. During September and October 1916, Boelcke scored 21 more victories while commanding Jagdstaffel 2, as he continued as the world's highest scoring ace. He was killed in a midair collision with his best friend on 28 October 1916. By the end of the war, Jagdstaffel 2 had 25 aces in its ranks; many of its aces were selected to lead other squadrons. Later, four of its members became generals during World War II. Boelcke's influence extends to the present, with extensive tributes to him at the German Air Force's Nörvenich Air Base and throughout Germany.

Early years

Oswald Boelcke was born on 19 May 1891, in Giebichenstein (since 1900 a City district of Halle (Saale)), Prussian Province of Saxony as the son of a schoolmaster. The Boelcke family had returned to the German Empire from Argentina six months before Oswald's birth.[1][2] His family name was originally spelt Bölcke, but Oswald and his elder brother Wilhelm (1886–1954) dispensed with the umlaut and adopted the Latin spelling in place of the German. The pronunciation is the same for both spellings.[3][4]

Oswald Boelcke caught whooping cough at age three, which resulted in lifelong asthma. In his fourth year, his father moved the family to Dessau near the Junkers factory in pursuit of professional advancement. The planes flying overhead were Oswald Boelcke's first exposure to aircraft.[4]

As Boelcke grew, he turned to athletics despite his asthma. Boelcke was of average size. In later life, he was described as being about 5 feet 7 inches (1.70 meters) tall, broad-shouldered and well proportioned, with great agility and "inexhaustible strength".[5][6] He played soccer and tennis, skated and danced. As a gymnast, he was considered the best in his school. He was an oarsman, and a prizewinning swimmer and diver. When he was 17, he became a skillful Alpinist capable of out-climbing his father and elder brother. His athletic prowess made him a popular leader on the school playing fields.[5]

He got along well in school with both his fellow students and the teachers; his frank and friendly demeanor, blond hair, and intense blue eyes made him memorable. One source says Oswald Boelcke was studious as well as athletic, excelling at mathematics and physics.[7][8]

Boelcke's family was a conservative one; they realized that a military career could move their son up the social ladder. Under this influence, while in the third or fourth form, the ten year old Oswald Boelcke had the audacity to write a personal letter to Kaiser Wilhelm requesting an appointment to military school. His wish was granted when he was 13, but once his parents were apprised of the opportunity by the belated reply letter, they objected and he did not attend Cadet School. He attended Herzog Friedrichs-Gymnasium (Duke Frederick's High School) instead of interrupting his education.[9][5]

His interest in a military career seemed undiminished. While he was in school, Boelcke's favorite author was the nationalist writer Heinrich von Treitschke. Boelcke also read publications from the German General Staff.[10][11] At age 17, for an elocution class, he chose three subjects—General Gerhard von Scharnhorst's military reforms, Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin's life before his aeronautical experiments, and the first airship flights. Despite his principal's reservations about his scholarship, Oswald Boelcke was awarded his Abitur honors degree on 11 February 1911.[10][12]

Entry into military service

After leaving school Boelcke joined a telegraph battalion in Koblenz as a Fahnenjunker (cadet officer) on 15 March 1911. As he learned his general military duties, he saw more airplanes than he had seen at home. He went on holiday leave on 23 December 1911.[13]

In January 1912, he began attending the Kriegsschule (Military Academy) in Metz. As the advent of spring lengthened the days, he took advantage of his early class dismissal to spend the rest of his daylight hours watching airplanes at a nearby airfield. In June, he stood his final exams. His written tests were graded as only "fair"; his oral exams were "good" or "very good"; his leadership skills were considered "excellent".[14]

In July 1912, he graduated and was commissioned as an ensign. Since Boelcke had gained his Abitur, his commission was pre-dated 23 August 1910, making him senior to the other new ensigns in his battalion. Promotion to lieutenant soon followed. He settled into a daily routine of training recruit telegraphers. His off-duty hours were spent in "a lovely, gay, active life".[15]

During 1913, he took advantage of a temporary posting to Metz to be taken on some flights with the 3rd Air Battalion. In October 1913, he was transferred to Darmstadt. On a visit to Frankfurt, he witnessed an aerobatic performance by pioneer French aviator Adolphe Pégoud. In February 1914, he competed in the officer's pentathlon, taking third place and qualifying for the 1916 Olympics scheduled for Berlin.[16]

World War I

1914

Without informing his family, Boelcke applied for a transfer to aviation duty. On 29 May 1914, he was accepted for pilot's training. On 2 June, he began instruction at the Halberstädter Fliegerschule (Halberstadt Flying School) in a six-week course. He passed his final pilot's exam on 15 August 1914. His first assignment was training 50 neophyte pilots on an Aviatik B.I.[17] World War I having begun on 4 August, Boelcke was anxious to see action. On 31 August, he connived his way into joining his older brother Wilhelm at Feldflieger Abteilung 13 (Field Flyer Detachment 13). On 1 September, the aircrew of Boelcke and Boelcke flew the first of many missions together. On 8 September, during reconnaissance of a French aerodrome, Wilhelm avoided a challenge by French aircraft because he feared they had machine guns aboard.[a] The brothers soon compiled a record of flying longer missions at more frequent intervals than the other aircrews, which caused some resentment within the unit. The two Boelckes continued to fly even as the weather worsened and the opposing armies' activities began to stagnate into trench warfare.[19][20] By year's end, Oswald, who had been last to join the section, had flown 42 sorties beyond the front line and Wilhelm had flown 61; the next most active airman had 27.[21][22]

1915

Catalyst for action

There was little ground combat and little need for air support during early 1915. Oswald spent a spell in hospital with asthma. Both brothers went on home leave.[23] The Boelckes' new commanding officer wished to separate them. In late March, matters came to a head when the brothers refused to fly separately and jumped the chain of command to complain but in April, they were parted. As Wilhelm returned to Germany, Oswald was posted to Feldflieger Abteilung 62 (Field Flyer Detachment 62) in La Brayelle, Douai, France on 25 April. He was quickly passed on to Kampfeinsitzerkommando Douai (Combat Single-Seater Command Douai), arriving 19 May. He was the most experienced pilot in the unit. His new assignment brought him friendship with Max Immelmann, a fellow citizen of the Prussian Province of Saxony serving in the unit.[24][25]

Advent of synchronized guns

At about this time, Roland Garros of France's Service Aéronautique (Aeronautical Service) rigged deflector wedges on his propeller in a crude pioneering try at firing a machine-gun dead ahead between the propeller blades. When he, Eugène Gilbert and Adolphe Pégoud scored their first aerial victories, they caught the public eye. French newspapers hailed Pégoud as "l'as", or ace.[b] Public imagination seized upon the novelty of aerial combat. The furore influenced aircraft design and pilot motivation for the remainder of the war. To an audience overwhelmed by a war of enormous scope and geographic complexity, simple stories of lone heroes had great appeal. German propagandists took advantage of this by supplying press releases to newspapers and magazines, and even encouraged printing of postcards and filming of popular aviators.[27][28]

The Fokker E.I Eindecker (monoplane) was a hasty response to these first air to air victories achieved by French fliers. The noses of five Eindeckers were each fitted with a forward-firing air-cooled Parabellum machine-gun connected to Anthony Fokker's pioneering gun synchronizer that prevented bullets from being fired when the propeller blades were in the line of fire. Aiming the aeroplane aimed the gun, much simplifying the task of attacking other aircraft.[29] The Eindecker machine-guns carried hundreds of bullets in ammunition belts; the few British Lewis guns in use had to be aimed indirectly around the propeller, and awkwardly reloaded after the 47 rounds in its ammunition drum had been fired. Fokkers were issued singly or in pairs to operational detachments.[30]

On 30 May 1915, Otto Parschau received a Parabellum-armed Fokker Eindecker prototype from Fokker, first owned and flown by Oberleutnant Waldemar von Buttlar.[31] He demonstrated it to his fellow pilots and trained the most promising of them to fly it. The wing warping controls made the monoplane difficult to fly. Among the students were Boelcke, Immelmann and Kurt Wintgens.[32] Anthony Fokker was also available as a flying coach.[33] The Eindeckers were to be flown when pilots were not on their assigned reconnaissance missions in their two-seaters. The German General Staff had settled on an aerial strategy of defensive "barrier" patrols over their own lines. The new aircraft were considered so revolutionary that they could not be risked over enemy lines for fear of capture. This restriction to defensive patrols was soon eroded by the insubordinate aggression of Boelcke and other Fokker fliers.[34][35]

Early fighter warfare

On 15 and 16 June 1915, Boelcke and his observer in an LVG C.I two-seater, armed solely with a rear gun, fought inconclusive combats against French and British aircraft.[33][36] On 17 June, on the French side of the lines, Gilbert shot down his fifth German aeroplane.[c] On 21 June, also operating from the Allied side of the lines, British pilot Lanoe Hawker scored his first victory.[37][38] In July 1915, Boelcke, Immelmann, Parschau, and Wintgens began to fly the Eindecker aircraft in combat.[39] As the German single-seat pilots began waging war in the third dimension, they had no tactical knowledge for reference. Until Boelcke recorded his experiences in July 1916, there was no tactical guide.[40]

On 1 July, Wintgens achieved the initial victory with the Fokker, but the French aircraft fell behind their own lines and went unverified—until after the war. On 4 July, Wintgens filed another victory claim—again only confirmed postwar. That day, Boelcke and his observer brought down an enemy two-seater in a prolonged engagement between reconnaissance machines. It was Boelcke's first victory, and the only one he scored in a two-seater, as he switched to the Eindecker.[41] By the end of July, Wintgens had two more victories, both verified.[42] On 1 August, Immelmann shot down his first aircraft.[43] By this time, the Eindecker pilots were being mentioned in official dispatches and lionized in magazine and newspaper. In letters home, Boelcke was already counseling his father about modesty in dealing with journalists.[41]

Boelcke and Immelmann often flew together. Boelcke won his first individual aerial combat on 19 August 1915 forcing down a British plane.[44] On 31 August, Pégoud was shot down and killed after six victories.[45] By then, Hawker had won six of his eventual seven victories, pretty much unnoticed.[38] In the glare of German publicity, Wintgens had claimed five victims, Boelcke two and Immelmann one.[46]

The ace race begins

September 1915 saw improved models of the Eindecker posted to the front; engine power was increased and the Fokker E.IV carried a pair of guns over the engine.[47] September also saw Boelcke and Immelmann score two victories apiece.[48] On 22 September, Boelcke was moved to Metz, joining the secretive Brieftauben-Abteilung-Metz (Carrier Pigeons Detachment Metz) to counter a French offensive.[49][50][d] On 1 November, the day after his sixth victory, Boelcke was awarded the Royal House Order of Hohenzollern. Immelmann duplicated the feat six days later, reaching six victories and also being awarded the Royal House Order of Hohenzollern.[51] By now, the deadly effect of the new aircraft on aerial warfare was beginning to be referred to by the British and French public as the Fokker Scourge.[52]

Boelcke moved back to Field Flieger Abteilung 62 on 12 December.[53] When he arrived, he was awarded a Prussian Lifesaving Medal for an act of heroism in late August. While watching French locals fishing from a high pier jutting into a canal, Boelcke saw a teen boy topple in and sink. Boelcke plunged in and saved the child from drowning. When French bystanders applauded his heroism, Boelcke was embarrassed by his soggy public appearance in his dress uniform.[54] By the end of 1915, Immelmann had seven victories,[43] Boelcke had six,[55] Wintgens had five (including two unconfirmed), [42] and Hans-Joachim Buddecke had four (one unconfirmed).[56] There were 86 Fokker and 21 Pfalz Eindeckers in service. Officially, the nine successful pilots of the Fokker Scourge had shot down 28 enemy aircraft.[57]

1916

Ace race continues

On 5 January 1916, the winter weather finally improved enough for flying. Boelcke shot down a British BE.2. Landing near the downed craft, he found that the German-speaking pilot knew of him. Boelcke had the two British airmen taken to hospital. He later visited the observer, bearing reading materials.[58] By now, Boelcke was so well known that this incident was front-page news.[59] On 12 January, Buddecke submitted his ninth combat claim but four had not been verified.[56][e] Boelcke and Immelmann shot down their eighth victims that day. These two were immediately presented the German Empire's most prestigious decoration, the Pour le Merite. This award sparked articles in the American and British press, as well as the German news. Boelcke was internationally famous. He could not walk German streets or attend the opera without being lionized.[61] Nor was it a case of only the ordinary populace being fascinated with their public hero; the young lieutenant now found that generals and nobility sought his company.[62]

On 21 January, Boelcke was again covertly posted to Brieftauben-Abteilung-Metz in anticipation of the Battle of Verdun. Bad weather limited his flying, and he complained he had little to do except reluctantly reply to fan mail. In late February, Boelcke was hospitalized with an intestinal ailment.[63] After about a week, he absconded from care to return to duty. He complained he was stationed too far from the front at Jametz and was given permission to use the forward airfield at Sivry only 12 km (7.5 mi) behind the lines. On 11 March, he was given command of the new Fliegerabteilung Sivry (Flying Detachment Sivry). This unit of six fighter pilots was the precursor of German fighter squadrons. Boelcke connected a front line observation post to the Sivry airfield and thus established the first tactical air direction center.[64] The new fighter unit was stationed near Stenay, which was the headquarters of Prussian Crown Prince Wilhelm. A friendship developed between the Crown Prince and the flier.[65]

On 3 March 1916, Boelcke was ordered to evaluate a new Eindecker prototype. His report pointed out shortcomings like inaccurately mounted guns and the limitations of its rotary engine. He also submitted a memorandum that criticized German use of airpower as "wretched".[66][67] Boelcke became the first aviator to score 10 victories on 12 March; the following day, even as he scored another, Immelmann scored one of the first double victories of the war to tie it up at 11 all.[68] The dead heat lasted for a week; on 19 March, Boelcke used his usual tactics of point-blank fire for victory number 12.[69] By this time, the obsolescent Fokker E.III was being replaced by newer Halberstadt D.II single-gun and twin-gun Albatros D.I biplane fighters, both types fitted with synchronized guns. The French counter to the Fokker Scourge was the new fast Nieuport 11. The British counter was the new Airco DH.2 pusher biplane that could shoot without use of synchronizing gear. Boelcke concentrated on developing fighter tactics, massing fighters in formation and using accurate gunnery in combat.[70][71]

The ace race continued, although Buddecke lost ground and was no longer a contender due to problems verifying some of his victories in Turkey. Now it became more of an "ace chase", with Immelmann playing catchup to Boelcke as their scores rose into the teens.[72] When Boelcke shot down two enemy aeroplanes on 21 May 1916, the emperor disregarded army regulations prohibiting promotion to Hauptmann until age 30. Oswald Boelcke was promoted to the rank ten days past his 25th birthday, making him the youngest captain in the German military.[73]

The ace race ends

Immelmann was killed on 18 June 1916 after his 17th victory. Boelcke, who then had 18 victories, was left the preeminent ace of the war. Upon Boelcke's return from Immelmann's funeral, Kaiser Wilhelm II ordered Boelcke grounded for a month to avoid losing him in combat soon after Immelmann. He had become such an important hero to the German public, as well as such an authority on aerial warfare, that he could not be risked. Boelcke downed his 19th victim before reporting to headquarters on 27 June.[74]

There the disgruntled flier was detailed to share his expertise with the head of German military aviation, Hermann von der Lieth-Thomsen, who was planning the reorganization of the German air service from the Fliegertruppe (Flying Troops) into the Luftstreitkräfte (Air Force). The Prussian military believed that a combat officer knows best which tactics will succeed. In conformance with this belief, Boelcke codified his successful mission tactics into the Dicta Boelcke. Its eight maxims seem self-evident, but Boelcke was the first to recognize them. His first six rules pointed out ways to gain an advantage in combat. The seventh counseled keeping a line of retreat, and the eighth mandated squadron teamwork. These rules were published in a pamphlet that was widely distributed throughout the Luftstreitkräfte as the original training manual on fighter tactics.[74][75]

During this interlude, the British launched their Somme offensive on 1 July. Their air assets amounted to 185 aircraft; the French were supplying 201 more. The opposing German force amounted to 129 aircraft, including 19 fighters. The British alone had 76 fighters in their force. Allied bombers began a campaign to destroy the German planes on their aerodromes.[76]

Journey to the east

On 10 July, Boelcke left on a tour of the Balkans. He transited Austria-Hungary to visit the Ottoman Empire. From his diary notes, the journey seemed a combination of military facility inspections, a celebrity tour, and a holiday. He kept attendance at formal social obligations to a minimum, but had to oblige such important hosts as Enver Pasha and Otto Liman von Sanders. Making his rounds of the Turkish flying units supported by the German Military Mission, Boelcke again met his friend Hans Joachim Buddecke. After a three-day beach vacation at Smyrna, Boelcke reached the quiescent Gallipoli battlefield on 30 July. When he returned to Constantinople, he learned that in his absence, the French and British airmen had taken air superiority from the Germans on the Western Front.[77]

On his hastened return trip, Boelcke visited Bulgaria and the Russian Front. Boelcke was visiting his brother Wilhelm at his unit in Kovel, a telegram arrived from Lieth-Thomsen:[78] "Return to west front as quickly as possible to organize and lead [Jagdstaffel 2 (lang] Error: {{Lang}}: invalid parameter: |3= (help)) on the Somme front."[79]

Creation of Jagdstaffel 2

When the message from headquarters reached the Boelcke brothers, it was followed by an extraordinary authorization. Six Kampfeinsitzerkommandos (Combat Single-Seater Commands) were expanded into Jagdstaffeln (|fighter squadrons), by orders issued on 10 August. The seventh planned squadron would be raised from scratch. This squadron, Jagdstaffel 2 (Fighter Squadron 2), was designated as Oswald Boelcke's to man and command. This authorization gave Boelcke a free hand to recruit fighter pilots for his new unit.[80]

Upon Wilhelm's recommendation, Oswald recruited a pair of pilots from Wilhelm's unit, both of whom he had previously met. One was a young cavalry officer, Manfred von Richthofen. The other was 37-year-old Erwin Böhme, a civil engineer returned from six years in Africa to reenlist in the military. After choosing three other pilots, Oswald Boelcke returned to France to organize his squadron.[81]

Boelcke started with only four empty buildings vacated by Feldflieger Abteilung 32 (Field Flyer Detachment 32) in the Vélu Woods. His new squadron was authorized 14 aircraft, the pilots to fly them, and ground crew to support them. As of 27 August, the fledgling squadron had three officers and 64 other ranks on strength, but no aircraft. By 8 September, there were eight pilots on board, including Richthofen and Böhme. Three days later, Böhme was pushing for permission to use his castoff Halberstadt; there were four aircraft in the squadron by then.[82][83]

While his squadron struggled into existence, Boelcke flew solo combat sorties, to be eagerly greeted upon his return by his pilots. On 2 September, Boelcke shot down Captain R. E. Wilson for victory number 20. The next day, Boelcke hosted Wilson in the squadron mess before returning the British flier to captivity.[84]

As new personnel continued to check in, facilities were built, and the squadron's pilots trained. They began with firing and troubleshooting machine guns on the ground. They also received extensive lectures from Boelcke on aircraft recognition and the strengths and flaws of opposing aircraft. They familiarized themselves with their Halberstadts before taking to the air.[85] Boelcke believed, "You can win the men's confidence if you associate with them naturally and do not try to play the high and mighty superior."[86]

Boelcke drilled them in his tactics as they flew. They learned to pair as leader and wingman, spaced 60 meters abreast to allow room for a U-turn without collision. They flew formation, massing their power for attacks. However, while attacking they split into pairs, although the Dicta Boelcke advised single assaults on the foe by flight leaders.[f] Meanwhile, Boelcke withheld the squadron from combat, and continued flying his solo sorties. Single victims fell to him on 8 and 9 September, and he scored double victories on the 14th and 15th.[88] When Boelcke returned to base with gunpowder soot on his chin, they knew he had shot down another enemy plane.[89] As Boelcke told them, "I only open fire when I can see the goggle strap on my opponent's crash helmet."[90]

Into battle

New fighters arrived on 16 September. There was a prototype Albatros D.II for Boelcke, and five Albatros D.Is to be shared by his pilots. The new aircraft outclassed any previous German aircraft, as well as those of their enemies. With more powerful engines, the new arrivals were faster, climbed more quickly to a higher ceiling, and carried two synchronized nose machine guns instead of one. With these new airplanes, Jagdstaffel 2 flew its first squadron missions on 17 September. Boelcke shot down his 27th victim, while his men shot down four more.[91]

Despite this initial success, squadron training continued. Boelcke now discussed flights beforehand and listened to his pilots' input. He then issued orders for the mission. Post flight, he debriefed his men.[92]

On 22 September, rainy weather had aggravated Boelcke's asthma to the point he could not fly. He refused to go to hospital, but devolved command on Oberleutnant Gunther Viehweger. That night, Jagdstaffel 2 transferred from Bertincourt to Lagnicourt because British artillery was beginning to shell its airfield. The next day, in a letter home, Boelcke noted he was still trying to impress his pilots that they should fight as a team instead of individually. Nevertheless, when the squadron flew six sorties that day without him, it shot down three enemy aircraft. Boelcke returned to flight status and command on the 27th.[92][93]

The squadron's September monthly activity report, written by Boelcke, reported 186 sorties flown, 69 of which resulted in combat. Ten victories were credited to him, and 15 more were shared among his men. Jagdstaffel 2 suffered four casualties.[94]

By 1 October, the squadron had ten pilots; besides Boelcke, five of them had shot down enemy aircraft. Boelcke scored his 30th victory, but the squadron lost a pilot to antiaircraft fire. The next day began a stretch of rainy weather that prevented flying until the 7th. On 8 October, General Erich Ludendorff reorganized the makeshift Fliegertruppe into the Luftstreitkräfte and appointed Generalleutnant Ernst von Hoeppner to the new post of Chief of Field Aviation. Hoeppner immediately had the Dicta Boelcke distributed within the new air force.[95]

On 10 October, a clear day saw the resumption of flying. Jagdstaffel 2 flew 31 sorties, fought during 18 of them, and claimed five victories, including Boelcke's 33rd. More air battles came on the 16th; among the four victories for the squadron were two more by Boelcke. His hot streak ran throughout the month; he scored 11 victories in October, with his 40th coming on 26 October. This total easily made him the leading ace of the war; this score would hold until Richthofen surpassed it on 13 April 1917. By this time, it was becoming obvious that the Royal Flying Corps had lost its mastery of the air. Jagdstaffel 2 had 50 victories to its credit—26 in October alone—with only six casualties. The German air service had suffered only 39 casualties between mid-September and mid-October, and had shot down 211 enemy aircraft.[96]

Boelcke's final mission

On the evening of 27 October, a depressed and tired Boelcke left the squadron mess early to return to his room. He complained of the racket in the mess to his batman, then sat staring into the fire. Böhme joined him, also stating the mess was too noisy. They shared a long talk, ending only when the orderly suggested bedtime.[97] The following day was misty with a cloud layer, but the squadron still flew four missions during the morning, as well as another later in the day. On the sixth mission, Boelcke and five of his pilots attacked a pair of British airplanes from 24 Squadron RFC. Boelcke and Böhme chased the Airco DH.2 of Captain Arthur Knight, while Richthofen pursued the other DH.2, flown by Captain Alfred McKay. McKay evaded Richthofen by crossing behind Knight, cutting off Boelcke and Böhme. Both of them jerked their planes upward to avoid colliding with McKay, each hidden from the other by their aircraft's wings. Neither was aware of the other's position. Just as Böhme spotted the other plane bobbing up below him, Boelcke's upper left wing brushed the undercarriage of Böhme's airplane. The slight impact split the fabric on the wing of Boelcke's Albatros. As the fabric tore away, the wing lost lift, and the aircraft spiralled lower to glide down into an impact near a German artillery battery near Bapaume. Although the crash seemed survivable, Boelcke was not wearing his crash helmet, nor was his safety belt fastened. He died of a fractured skull.[98][99][100] Böhme returned to base and overturned while landing, blanking the accident from his mind in his distress. He lamented, "Destiny is generally cruelly stupid in her choices..." but he was exonerated by an enquiry.[101][102]

In memoriam

Pilots from Jagdstaffel 2 rushed forward to the artillery position where Boelcke had crashed, hoping he was still alive. The gunners handed over his body to them.[98] Despite Boelcke being Protestant, his memorial service was held in the Catholic Cambrai Cathedral on 31 October. Among the many wreaths, there was one from Captain Wilson and three of his fellow prisoners; its ribbon was addressed to "The opponent we admired and esteemed so highly". Another wreath of British origin had been air dropped at the authorization of the Royal Flying Corps; it read "To the memory of Captain Boelcke, our brave and chivalrous opponent".[102][103]

Rupprecht, Crown Prince of Bavaria attended the ceremony and two generals spoke at the service. Richthofen preceded the coffin from the cathedral, displaying Boelcke's decorations. The sun broke through the gloom as the coffin was placed on a gun caisson. Idling aircraft criss-crossed overhead in tribute. The journey to a waiting train passed through an honor guard to the sound of rifle salutes, followed by a hymn. The train crept away through Magdeburg and Halberstadt to Dessau.[103] When the train arrived in Dessau the next day, Boelcke was taken to his home church, Saint John's and laid out before the altar, attended by an honor guard of decorated sergeant pilots. Condolences, decorations and honors flooded in from the crowned heads of Europe. When the funeral service was held on the afternoon of 2 November, the crowd was packed with royalty, generals and nobility. General Moriz von Lyncker gave Boelcke's funeral oration, followed by a speech by Lieth-Thomsen. Oswald Boelcke was buried in the Ehrenfriedhof (Cemetery of Honor).[104]

Legacy

His pre-eminent student, Manfred von Richthofen, summed up the mourning with his comment, "Boelcke had not a personal enemy. He was equally polite to everybody, making no differences".[105]

Boelcke was the progenitor of air to air combat tactics, fighter squadron organization, early warning systems, and the German air force; he has been dubbed "the father of air combat".[55][106] From his first victories onward, the news of his success both instructed and motivated both his fellow fliers and the German public. It was at his instigation that the Imperial German Air Service founded its Jastaschule (Fighter School) to teach aerial tactics. The promulgation of his Dicta Boelcke set tactics for the German fighter force. The concentration of fighter airplanes into squadrons gained Germany air supremacy on the Western Front, and was the basis for their wartime successes.[107]

Jagdstaffel 2 was re-named Jagdstaffel Boelcke and remained one of Germany's premier fighter squadrons after Boelcke's death, outscoring all but one other Jagdstaffel. The 336 victories the Jagdstaffel Boelcke scored during the war came at the price of 44 casualties.[108]

Of the first 15 pilots chosen by Boelcke, eight became aces—seven of them within the squadron. Three of the 15, at various times, commanded the Jagdstaffel. By war's end, 25 aces had served in the squadron and accounted for 90 per cent of its victories.[109] Four of its aces became generals during World War II – Gerhard Bassenge, Ernst Bormann, Hermann Frommherz, and Otto Höhne.[110] The most notable of Boelcke's original roster of pilots was Manfred von Richthofen.[111] The Red Baron acknowledged Boelcke's influence in the Richthofen Dicta; indeed, the opening sentence of his tactical manual for wing operations refers to Boelcke. The Richthofen Dicta section entitled "The One to One Battle" quotes Boelcke. And, as was done with Dicta Boelcke, the Richthofen Dicta was distributed service-wide by the German High Command.[112]

Boelcke was one of the few German heroes of World War I not tainted by association with the Nazi cause.[113] Nevertheless, Nazi Germany named Kampfgeschwader 27 (Bomber Wing 27) for Boelcke.[114] Also, Boelcke's barracks a Luftwaffe barracks named after him, later became a subcamp of the Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp.[115] There is a Boelcke-Straße (Boelcke Street) in Berlin.[116] There is a Boelcke-Kaserne (Boelcke Barracks) in Koblenz, located on another Boelcke-Straße.[117] Still another Boelcke-Straße extends northwest from Kerpen, leading to two Boelcke-Kaserne in separate locations.[118] There's also an officers clubhouse named for Boelcke on a military installation, near the northern Boelcke-Kaserne located on the base.[119]

Boelcke's name appears on the coat of arms of the present-day German Air Force fighter-bomber wing Taktisches Luftwaffengeschwader 31 (Tactical Air Force Wing 31). The wing conducts a pilgrimage to Boelcke's grave on the anniversary of his death. He is also extensively commemorated on the wing's home airfield at Norvenich Air Base. He is memorialized by murals on base buildings, portraits in their halls, and a bust in the headquarters entry. The base magazine is named for him. An aircraft tail section on static display is emblazoned with his name and a painting of his Fokker.[114]

Awards and honors

Prussian/Imperial German awards

- Pour le Mérite[120]

- Royal House Order of Hohenzollern, Knight's Cross with Swords[120]

- Iron Cross: First and Second Class[120]

- Lifesaving Medal[120]

Other German awards

- House Order of Albert the Bear, Knight's Cross, 1st and 2nd class[120]

- Friedrich Cross, 2nd class[120]

- Military Merit Order, 4th class with Swords[120]

Duchies of Saxe-Altenburg, Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, and Saxe-Meiningen joint award:

- Knight of the Military Merit Order[120]

Foreign awards

- Order of the Iron Crown, 3rd class with war decoration[120]

- Order of Bravery, 3rd class[120]

Honors

- By order of the Emperor, Jagdstaffel 2 was renamed as Jagdstaffel Boelcke on 17 December 1916.[121]

References

Footnotes

- ^ During this time, without quite realizing it, the French had achieved air superiority for the first time in history.[18]

- ^ Russian flier Pyotr Nesterov had scored the first aerial victory in history in Russia on 25 August 1914, virtually unnoticed.[26]

- ^ According to Smithsonian's Air & Space website, at this stage of the war the definition of an ace was not yet fixed at five victories. They state that Americans, afraid that their belated entry into the war would deny their fliers opportunity to become aces, lobbied the British to lower the requirement for becoming an ace from ten victories to five. Other sources say the French were already using the term as early as June 1916. The Germans originally attached significance to achieving four or ten victories.

- ^ The odd name was used to disguise its existence as a combat unit.[50]

- ^ Buddecke was flying with the Ottoman Aviation Squadrons during the Gallipoli Campaign; he would receive the third fighter pilot's award of the Pour le Merite on 14 April 1916 after seven of his victories were confirmed.[60]

- ^ French squadrons had already pioneered flying formation into combat. However, when they attacked, every French pilot fought individually.[87]

Notes

- ^ Werner (2009), pp. 10–11.

- ^ Head (2016), p. 38.

- ^ Werner (2009), p. 10.

- ^ a b Head (2016), pp. 38–39.

- ^ a b c Head (2016), p. 39.

- ^ Werner (2009), pp. 13–14.

- ^ Head (2016), pp. 39–40.

- ^ Werner (2009), pp. 11–12.

- ^ Werner (2009), pp. 11, 15–16.

- ^ a b Head (2016), p. 40.

- ^ Werner (2009), pp. 12–14.

- ^ Werner (2009), p. 15.

- ^ Head (2016), p. 42.

- ^ Head (2016), pp. 42–43.

- ^ Head (2016), p. 43.

- ^ Head (2016), p. 44.

- ^ Head (2016), pp. 44–45, 48–49.

- ^ Head (2016), p. 58.

- ^ Head (2016), p. 51.

- ^ Werner (2009), pp. 75–77, 81–82, 85, 90, 99, 101.

- ^ Werner (2009), pp. 90, 95.

- ^ Head (2016), p. 53.

- ^ Head (2016), p. 54.

- ^ Head (2016), pp. 60–62.

- ^ Werner (2009), pp. 101–103.

- ^ Kulikov (2013), pp. 7–8.

- ^ Head (2016), pp. 30, 60, 68.

- ^ Robertson (2005), pp. 100–103.

- ^ VanWyngarden (2006), pp. 6–9.

- ^ Head (2016), p. 70.

- ^ Scott (2012), p. 32.

- ^ VanWyngarden (2006), pp. 9–10.

- ^ a b Werner (2009), p. 127.

- ^ Werner (2009), pp. 111–115.

- ^ Head (2016), pp. 63–66, 68.

- ^ Head (2016), pp. 68–69.

- ^ Head (2016), p. 30.

- ^ a b Shores, Franks & Guest (1990), p. 188.

- ^ Franks (2004), p. 11.

- ^ Head (2016), pp. 67–69, 97.

- ^ a b Head (2016), pp. 67–69.

- ^ a b Franks, Bailey & Guest (1993), pp. 231–232.

- ^ a b Franks, Bailey & Guest (1993), pp. 134–135.

- ^ Head 2016, p. 69.

- ^ Franks & Bailey (1993), p. 202.

- ^ Franks, Bailey & Guest (1993), pp. 76, 134–135, 231–232.

- ^ VanWyngarden (2006), pp. 21, 25.

- ^ Franks, Bailey & Guest (1993), pp. 76, 135.

- ^ VanWyngarden (2006), p. 23.

- ^ a b Head (2016), p. 72.

- ^ Head (2016), p. 78.

- ^ VanWyngarden (2006), p. 24.

- ^ Werner (2009), pp. 159–160.

- ^ Head (2016), p. 71.

- ^ a b Franks, Bailey & Guest (1993), p. 76.

- ^ a b Franks, Bailey & Guest (1993), pp. 88–89.

- ^ Franks (2008), p. 41.

- ^ Werner (2009), pp. 161–162.

- ^ Head (2016), p. 81.

- ^ Franks, Bailey & Guest (1993), p. 88.

- ^ Head (2016), pp. 82–83.

- ^ Werner (2009), pp. 168–171.

- ^ Werner (2009), pp. 171–172.

- ^ VanWyngarden (2006), p. 34.

- ^ Head (2016), pp. 88–89.

- ^ Werner (2009), pp. 183–186.

- ^ Head (2016), p. 91.

- ^ VanWyngarden (2006), pp. 36–37.

- ^ VanWyngarden (2006), p. 50.

- ^ VanWyngarden (2006), p. 51.

- ^ Head (2016), pp. 85–86.

- ^ Franks, Bailey & Guest (1993), pp. 76–77, 88–89, 134–135.

- ^ Head (2016), pp. 92–93.

- ^ a b VanWyngarden (2006), p. 63.

- ^ Head (2016), pp. 59, 97–98.

- ^ Head (2016), pp. 104–105.

- ^ Werner (2009), pp. 213–235.

- ^ VanWyngarden (2006), p. 69.

- ^ Werner (2009), p. 228.

- ^ Head (2016), pp. 109–111.

- ^ Head (2016), pp. 111–112.

- ^ VanWyngarden (2006), p. 75.

- ^ Head (2016), pp. 110–111.

- ^ Head (2016), pp. 113–114.

- ^ Head (2016), pp. 112–114.

- ^ Head (2016), p. 63.

- ^ Head (2016), p. 88.

- ^ Head (2016), p. 100.

- ^ Head (2016), p. 114.

- ^ VanWyngarden (2007), p. 60.

- ^ Head (2016), pp. 121–124.

- ^ a b Head (2016), p. 127.

- ^ Werner (2009), pp. 241–242.

- ^ Head (2016), p. 128.

- ^ Head (2016), p. 131.

- ^ Head (2016), pp. 132–136.

- ^ Head (2016), p. 138.

- ^ a b VanWyngarden (2007), p. 22.

- ^ Head (2016), pp. 139–140.

- ^ VanWyngarden (2016), p. 8.

- ^ Head (2016), p. 141.

- ^ a b VanWyngarden (2007), p. 23.

- ^ a b Head (2016), pp. 141–145.

- ^ Head (2016), pp. 142–143, 147.

- ^ Richthofen (2011), pp. 116–118.

- ^ Head (2016), Cover, title page, 40, 186.

- ^ Head (2016), pp. 168–170.

- ^ VanWyngarden (2007), pp. 27, 118–119.

- ^ Head (2016), pp. 167–168, 174, 198.

- ^ Franks, Bailey & Guest (1993), pp. 66, 83, 111.

- ^ Franks, Bailey & Guest (1993), p. 188.

- ^ Head (2016), pp. 207–209.

- ^ VanWyngarden (2016), pp. 8, 15.

- ^ a b Head (2016), pp. 175–176.

- ^ USHMM (2009), p. 990.

- ^ Google map of Berlin [1]. Accessed 1 April 2022.

- ^ Google map of Koblenz [2] Accessed 1 April 2022.

- ^ First Google map of Kerpen

- ^ Second Google map of Kerpen [3] Accessed 1 April 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Head (2016), p. 147.

- ^ Head (2016), p. 149.

Bibliography

- Franks, Norman (2008). Sharks Among Minnows. London: Grub Street. ISBN 978-1-902304-92-2.

- Franks, Norman (2004). Jasta Boelcke: The History of Jasta 2, 1916–18. London: Grub Street. ISBN 978-1-904010-76-0.

- Franks, Norman; Bailey, Frank (1993). Over the Front: The Complete Record of the Fighter Aces and Units of the United States and French Air Services, 1914–1918. London: Grub Street. ISBN 978-0-948817-54-0.

- Franks, Norman; Bailey, Frank; Guest, Russell (1993). Above the Lines: A Complete Record of the Aces and Fighter Units of the German Air Service, Naval Air Service and Flanders Marine Corps 1914–1918. London: Grub Street. ISBN 978-0-948817-73-1.

- Head, R. G. (2016). Oswald Boelcke: Germany's First Fighter Ace and Father of Air Combat. London: Grub Street. ISBN 978-1-910690-23-9.

- Kulikov, Victor (2013). Russian Aces of World War I. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-78096-059-3.

- Richthofen, Manfred, Captain (2011). The Red Battle Flyer. Translated by Barker, T. Ellis. New York: CruGuru. ISBN 978-192041-463-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Robertson, Linda R. (2005). The Dream of Civilized Warfare: World War I Flying Aces and the American Imagination. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-4271-7.

- Scott, Josef (2012). Fokker Eindecker Compendium. Vol. I. Berkhampstead: Albatros Publications. ISBN 978-1-906798-22-2. Retrieved 11 April 2015.

- Shores, Christopher; Franks, Norman; Guest, Russell (1990). Above the Trenches: A Complete Record of the Fighter Aces and Units of the British Empire Air Forces, 1915–1920. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 978-0-919195-11-0.

- USHMM (2009). Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933–1945. Vol. I. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. ISBN 978-0-253-35328-3.

- VanWyngarden, Greg van (2006). Early German Aces of World War I. Aircraft of the Aces No. 73. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84176-997-4.

- VanWyngarden, Greg van (2007). Jagdstaffel 2 'Boelcke' Von Richthofen's Mentor. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84603-203-5.

- VanWyngarden, Greg van (2016). Aces of Jagdgeschwader Nr III. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-47280-843-1.

- Werner, Johannes (1942). Boelcke der Mensch, der Flieger, der Führer der deutschen Jagdfliegerei [Boelcke the Man, the Aviator, the Leader of German Fighter Aviation] (in German). Leipzig: K.F. Koehler Verlag. OCLC 315312363. Translated and published in English as Knight of Germany: Oswald Boelcke, German Ace. Havertown, PA: Casemate (2009), first edition (1985) ISBN 978-1-935149-11-8

Further reading

- Guttman, Jon (2009). Pusher Aces of World War 1. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84603-417-6.

- Kilduff, Peter (2012). Iron Man Rudolf Berthold: Germany's Indomitable World War I Fighter Ace. London, UK: Grub Street. ISBN 978-1-908117-37-3.

- Pappalardo, Joe (23 June 2014). "The Texas Air Base Where NATO Fighter Pilots Are Forged". Popular Mechanics. Retrieved 24 August 2018.

External links

- 1891 births

- 1916 deaths

- People from the Province of Saxony

- People from Halle (Saale)

- Aerial warfare pioneers

- Aviators killed in aviation accidents or incidents in France

- German military personnel killed in World War I

- Prussian Army personnel

- German World War I flying aces

- Luftstreitkräfte personnel

- Recipients of the Pour le Mérite (military class)

- Recipients of the Imtiyaz Medal