Tomboy

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

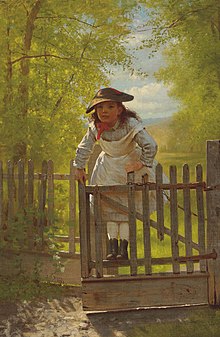

A tomboy is a term for a girl or a young woman with masculine qualities. It can include wearing androgynous or unfeminine clothing and actively engage in physical sports or other activities usually associated with boys.[1]

Etymology

The word "tomboy" is a portmanteau which combines a common boy's name "Tom" with "boy". Though this word is now used to refer to "boy-like girls", the etymology suggests the meaning of tomboy has changed drastically over time. Records show that Tomboy used to refer to boisterous male children in the mid-16th century.[2]

It's uncertain when "tomboy" began to refer to "boyish girls". After young women challenged the traditional definition of a girl during the first wave of feminism, the term tomboy now refers to sport-spirited, boisterous girls and young woman with often an androgynous or masculine style of dress.[3]

The name “Tom,” short for “Thomas,” has often been used as “a generic name for any male representative of the common people,” according to the Oxford English Dictionary. A good illustration is the expression “every Tom, Dick, and Harry.”[4] “Tom” has been used in this way, more or less as a quasi-name or nickname for an ordinary man, since the 1300s. To cite another example, in the 1600s, speakers of English used the expression “Tom of all trades” as well as “Jack of all trades.[4]” And in the 1700s, people began using “tom” as a lower-case noun for a male animal (as in “tom cat,” “tom turkey,” etc.). How did Tomboy get this meaning? Here's one possibility. Since “Tom” was a name for the common or archetypal male, a particularly rowdy boy was perhaps called a “Tom boy” as another way of saying he was especially boyish – a boy's boy, in other words. “Tomboy” soon took on another meaning, according to the OED, that of “a bold or immodest woman.”[4]

History

Pre-16th century and origin

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (September 2022) |

In the United States

Pre-19th century

Before mid 19th century, middle-and upper-class white women equated femininity with fragility during the early decades of the nineteenth century. Under the auspices of what has come to be known as the “Cult of True Womanhood”,[5] physical strength, emotional fortitude, and constitutional vigor were considered unwomanly.[5] Mothers and wives prided themselves on being frail and raised their daughters in accordance with these beliefs. Women cinched their corsets tightly and instructed their daughters to avoid strenuous exercise and sports, making themselves to feeble ornamental objects for their brothers, husbands and fathers.[5]

During the mid-nineteenth century, however, this paradigm began to change.[5] The era's increasing economic instability made the fragile femininity no longer desirable. During a period that predated government regulation of business practices, the US economy was unstable.[5] Since the economic future of the American family was insecure, it became clear that girls from all socio-economic strata needed to learn practical job skills. Displays of feminine refinement would not put food on the table in the event of a financial crisis. This new mandate for female participation in family financial matters called for an alteration to both current childrearing practices and standards of feminine beauty.[5] Because the time may come when adolescent girls and young women would be called upon to support their families, they could no longer afford to be weak, ill, and languishing. Instead of deeming female health, strength and vigor unattractive, society now considered these qualities desirable in the nation's young women.[5] Together with the birth of white feminism and the increasingly unstable economy, the era's turbulent political climate formed a final factor in the antebellum emergence of tomboys.[5]

Abate stated that this mode of behavior was planned to enhance the power and durability of the country's coming brides and child-bearers and the progeny that they birthed. She explained that tomboyism was more than a new fostering method or gender statement for the country's young women; it was also a way to improve the genetic quality of the human population and at least a way to assert white racial supremacy.[6]

In her 1898 book Women and Economics, feminist writer Charlotte Perkins Gilman lauds the health benefits of being a tomboy as well as the freedom for gender exploration: "not feminine till it is time to be".[7]

Joseph Lee, a playground advocate, wrote in 1915 that the tomboy phase was crucial to physical development between the ages of 8 and 13.[8] Tomboyism remained popular through World War I and World War II in society, literature, and then film.

Connection with White Racial Supremacy

Though the social acceptance of tomboyism freed women from the “cult of true womanhood[9],” the reasons for this push to give girls some aspect of boyhood were ultimately racist. Among American-born whites in the mid-19th century, those white women were restricted by organ-damaging corsets and hindered by bustles and crinolines, which not only impacted their health, but also discouraged from physical activity and an outdoor life. Thus, there was a decline of birth rate because of the concerning health status of middle and upper class white women[10]. Meanwhile, foreign immigration increased, causing a nativist backlashamong some White Americans. The fear of the black taking over the white class in the US was the main incentive for people to pay attention to white young women's health conditions[11]. Tomboyism was seen as a system of behavior that would improve the constitution of White girls. “Good health” was code: tomboy child now, successful procreator later to assert white racial supremacy[12].

Mid-19th century and First Wave Feminism

Growing up under the advocacy of physical fitness and Playground Movement, these middle- and- upper-class White girls experienced in childhood profoundly changed some of them, not because it made them more reproductive, but because it made them feel they deserved equality with men, even if that equality excluded women of color. Being a tomboy was a way to wriggle out of the cult of domesticity and few wanted to go back in. By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the tomboy was everywhere, dovetailing with both women’s suffrage and first-wave feminism[13]. Some of these tomboys grow up to become the leaders of first-wave feminism or extraordinary first-ever female leaders, such as Frances Willard who became one of the country’s most important suffragists and Elizabeth and Emily Blackwell and Sara Josephine Baker who became some of the country’s first female doctors. In fact, in the Journal "American Tomboys, 1850–1915," Historian Reneé Sentilles went through volumes of biographies of exceptional 19th- and early 20th-centiry women, finding that every single one of them claimed to have been a childhood tomboy, or at least had a family that was receptive to a tomboyish upbringing[14].

Late 19th century and Civil War

Whereas the mid 19th century began to recognize the need for healthy white women, the Civil War period became convinced of it.[15] Throughout the North and the South, the outbreak of hostilities and the exodus of thousands of men for the battlefield precipitated a crisis that compelled many adolescent girls and young women to engage in an array of gender-bending behaviors. With their husbands, fathers and brothers away, girls and young women took on lists of formerly male roles and responsibilities.[15] Although formerly banned to own property or hold bank accounts, many were now left in charge of their family's finances which gave the women independence.[15] Similarly, whereas preciously barred from participating in government, some women were now largely responsible for maintaining civic law and order.[15] Finally, while expected to rely on male protection before, scores of wives and mothers were placed in the position of defending their homes from invading troops.[15] As a result, many women who may not have considered themselves gender iconoclasts before the Civil War found themselves engaging in an array of tomboyish actions during it. The large-scale involvement of women during the Civil War, in fact, prompted tomboyism as women were given the duties of men.[15]

Tomboy, gender roles, and gender reformation

Gender roles and stereotypes

The idea that there are girl activities and clothing, and that there are boy activities and clothing, is often reinforced by the tomboy concept. Tomboyism can be seen as both refusing gender roles and traditional gender conventions, but also conforming to gender stereotypes.[16] The concept may be considered outdated or looked at from a positive viewpoint.[17] Feminine traits are often devalued and unwanted, and tomboys often respond this viewpoint, especially toward girly girls. This can be due in part to an environment that desires and only values masculinity, depending on the decade and geographical region. Idealized male masculinity is atop the hegemony and sets the traditional standard, and is often upheld and spread by young children, especially through children playing with one another. Tomboys may view femininity as having been pushed on them, which results in negative feelings toward femininity and those that embrace it. In this case, masculinity may be seen as a defense mechanism against the harsh push toward femininity, and a reclaiming of agency that is often lost due to sexist ideas of what girls are and are not able to do.[18]

Tomboys are expected in some cultures to one day cease their masculine behavior. In those cultures, usually, during or right before puberty, they will return to feminine behavior, and are expected to embrace heteronormativity. Tomboys who do not do such are occasionally stigmatized, usually due to homophobia. Creed argues that the tomboy's "image undermines patriarchal gender boundaries that separate the sexes", and thus is a "threatening figure".[19] This "threat" affects and challenges the idea of what a family must look like, generally nuclear independent heterosexual couplings with two children.[20]

Gender scholar Jack Halberstam argues that while the defying of gender roles is often tolerated in young girls, adolescent girls who show masculine traits are often repressed or punished.[16] However, the ubiquity of traditionally female clothing such as skirts and dresses has declined in the Western world since the 1960s, where it is generally no longer considered a male trait for girls and women not to wear such clothing. An increase in the popularity of women's sporting events (see Title IX) and other activities that were traditionally male-dominated has broadened tolerance and lessened the impact of tomboy as a pejorative term.[1] As sociologist Barrie Thorne suggested, some "adult women tell with a hint of pride as if to suggest: I was (and am) independent and active; I held (and hold) my own with boys and men and have earned their respect and friendship; I resisted (and continue to resist) gender stereotypes".[21]

In the Philippines, tomboys are masculine-presenting women who have relations with other women, with the other women tending to be more feminine, although not exclusively, or transmasculine people who have relationships with women; the former appears more common than the latter.[22] Women who engage in romantic relationships with other women, but who are not masculine, are often still deemed heterosexual. This leads to more invisibility for those that are lesbian and feminine.[23] Scholar Kale Bantigue Fajardo argues for the similarity between "tomboy" in the Philippines and "tombois in Indonesia", and "toms in Thailand" all as various forms of female masculinity.[22]

Tomboy and sexual orientation

Sexual orientation and Misconception

During the 20th century, Freudian psychology and backlash against LGBT social movements resulted in societal fears about the sexualities of tomboys, and this caused some to question whether tomboyism leads to lesbianism.[6] Throughout history, there has been a perceived correlation between tomboyishness and lesbianism.[24][16] For instance, Hollywood films would stereotype the adult tomboy as a "predatory butch dyke".[16] Lynne Yamaguchi and Karen Barber, editors of Tomboys! Tales of Dyke Derring-Do, argue that "tomboyhood is much more than a phase for many lesbians"; it "seems to remain a part of the foundation of who we are as adults".[24][25] Many contributors to Tomboys! linked their self-identification as tomboys and lesbians to both labels positioning them outside "cultural and gender boundaries".[24] Psychoanalyst Dianne Elise's essay in 1995 reported that more lesbians noted being a tomboy than straight women.[26] However, while some tomboys later reveal a lesbian identity in their adolescent or adult years, behavior typical of boys but displayed by girls is not a true indicator of one's sexual orientation.[27] With raising female liberation and gender-neutral playgrounds (at least in the US) in the 21st century, more and more girls are technically “tomboys” without being referred as “tomboys” because it is normal nowadays for girls to engage in physical activities, play equally with boys, and wear pants or gender-neutral clothing. The association between lesbianism and tomboyism is not only outdated but also disrespectful to both the girl and the lesbian community.[citation needed]

Tomboy representations in media

Fiction

Tomboys in fictional stories are often used to contrast a more girly and traditionally feminine character. These characters are also often the ones that undergo a makeover scene in which they learn to be feminine, often under the goal of getting a male partner. Usually with the help of the more girly character, they transform from an ugly duckling into a beautiful swan, ignoring past objectives and often framed in a way that they have become their best self.[19] Doris Day's character in Calamity Jane is one example of this;[28] Allison from The Breakfast Club is another.[29] Tomboy figures who do not eventually go on to conform to feminine and heterosexual expectations often simply remain in their childhood tomboy state, eternally ambiguous. The stage of life where tomboyism is acceptable is very short and rarely are tomboys allowed to peacefully and happily age out of it without changing and without giving up their tomboyness.[28]

Tomboyism in fiction often symbolizes new types of family dynamics, often following a death or another form of disruption to the nuclear family unit, leading families of choice rather than a descent. This provides a further challenge to the family unit, including often critiques of socially who is allowed to be a family – including critiques of class and often a women's role in a family. Tomboyism can be argued to even begin to normalize and encourage the inclusion of other marginalized groups and types of families in fiction including, LGBT families or racialized groups. This is all due to the challenging of gender roles, and assumptions of maternity and motherhood that tomboys inhabit.[28]

Tomboys are also used in patriotic stories, in which the female character wishes to serve in a war, for a multitude of reasons. One reason is patriotism and wanting to be on the front lines. This often ignores the many other ways women were able to participate in war efforts and instead retells only one way of serving by using one's body. This type of story often follows the trope of the tomboy being discovered after being injured, and plays with the particular ways bodies get revealed, policed and categorized. This type of story is also often nationalistic, and the tomboy is usually presented as the hero that more female characters should look up to, although they still often shed some of their more extreme ways after the war.[28]

See also

References

- ^ a b Who Are Tomboys and Why Should We Study Them?, SpringerLink, Archives of Sexual Behavior, Volume 31, Number 4

- ^ King, Elizabeth (Jan 5, 2017). "A Short History of the Tomboy". Atlantic. Retrieved Nov 22, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Davis, Lisa (August 11, 2020). Tomboy: The Surprising History and Future of Girls Who Dare to Be Different. New York: Legacy Lit. pp. 7–11. ISBN 978-0316458313.

- ^ a b c O’Conner, Patricia (May 22, 2010). "Who is the Tom in tomboy?". Grammarphobia. Retrieved Nov 22, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h Abate, Michelle Ann (2008-06-28). Tomboys: A Literary and Cultural History. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. pp. 4–6. ISBN 978-1-59213-724-4.

- ^ a b Abate, Michelle Ann (2008). Tomboys: A Literary and Cultural History. Temple University Press. ISBN 978-1-59213-722-0.

- ^ Gilman, Charlotte Perkins (1898). Women and Economics. Boston: Small, Maynard & Company. p. 56.

- ^ Lee, Joseph (1915). Play in Education. pp. 392–393.

- ^ Abate, Michelle Ann (2008-06-28). Tomboys: A Literary and Cultural History. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. pp. 4–6. ISBN 978-1-59213-724-4

- ^ Davis, Lisa Selin (2020-08-17). "Are you a woman who votes? Thank a tomboy". CNN. Retrieved 2022-11-30

- ^ Abate, Michelle Ann (2008-06-28). Tomboys: A Literary and Cultural History. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. pp. 4–6. ISBN 978-1-59213-724-4.

- ^ Abate, Michelle Ann (2008). Tomboys: A Literary and Cultural History. Temple University Press. ISBN 978-1-59213-722-0.

- ^ "A Short History of the Tomboy". Bunk. Retrieved 2022-11-30

- ^ Cassandra N Berman, American Tomboys, 1850–1915. Childhoods: Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Children and Youth. By Renée M. Sentilles, Western Historical Quarterly, Volume 50, Issue 3, Autumn 2019, Pages 317–318, https://doi.org/10.1093/whq/whz049

- ^ a b c d e f Abate, Michelle Ann (2008-06-28). Tomboys: A Literary and Cultural History. Philadelphia, USA: Temple University Press. pp. 24–16. ISBN 978-1-59213-724-4.

- ^ a b c d Halberstam, Judith (1998). Female Masculinity. Duke University Press. pp. 193–196. ISBN 0822322439. Archived from the original on 2018-04-29. Retrieved 2019-12-18.

Hollywood film offers us a vision of the adult tomboy as the predatory butch dyke: in this particular category, we find some of the best and worst of Hollywood stereotyping.

- ^ Halberstam, Judith (1988). Female Masculinity. doi:10.1215/9780822378112. ISBN 978-0-8223-2226-9. Archived from the original on 2018-04-29. Retrieved 2019-12-18.

- ^ Harris, Adrienne (2000-07-15). "Gender as a Sort Assembly Tomboys' Stories". Studies in Gender and Sexuality. 1 (3): 223–250. doi:10.1080/15240650109349157. ISSN 1524-0657. S2CID 144985570.

- ^ a b Creed, Barbara (2017-09-25), "Lesbian Bodies: Tribades, Tomboys and Tarst", Feminist Theory and the Body, Routledge, pp. 111–124, doi:10.4324/9781315094106-13, ISBN 978-1-315-09410-6

- ^ Proehl, Kristen Beth, 1980-. Battling girlhood : sympathy, race and the tomboy narrative in American literature. OCLC 724578046.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Thorne, Barrie (1993). Gender play: boys and girls in school. Rutgers University Press. p. 114. ISBN 0-8135-1923-3.

- ^ a b Fajardo, K. B. (2008-01-01). "TRANSPORTATION: Translating Filipino and Filipino American Tomboy Masculinities through Global Migration and Seafaring". GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies. 14 (2–3): 403–424. doi:10.1215/10642684-2007-039. ISSN 1064-2684. S2CID 142268960.

- ^ Nadal, Kevin L.; Corpus, Melissa J. H. (September 2013). ""Tomboys" and "baklas": Experiences of lesbian and gay Filipino Americans". Asian American Journal of Psychology. 4 (3): 166–175. doi:10.1037/a0030168. ISSN 1948-1993.

- ^ a b c Brown, Jayne Relaford (1999). "Tomboy". In B. Zimmerman (ed.). Encyclopedia of Lesbian Histories and Cultures. Routledge. pp. 771–772. ISBN 0815319207. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

The word [tomboy] also has a history of sexual, even lesbian, connotations. [ ... ] The connection between tomboyism and lesbianism continued, in a more positive way, as a frequent theme in twentieth-century lesbian literature and nonfiction coming out stories.

- ^ Yamaguchi, Lynne and Karen Barber, ed. (1995). Tomboys! Tales of Dyke Derring-Do. Los Angeles: Alysson.

- ^ King, Elizabeth (2017-01-05). "A Short History of the Tomboy". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 2017-01-08. Retrieved 2017-01-06.

- ^ Gabriel Phillips & Ray Over (1995). "Differences between heterosexual, bisexual, and lesbian women in recalled childhood experiences". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 24 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1007/BF01541985. PMID 7733801. S2CID 23296942.

- ^ a b c d Proehl, Kristen Beth, 1980–. Battling girlhood : sympathy, race and the tomboy narrative in American literature. OCLC 724578046.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "She's Not All That: A Brief History of Rags-to-Princess Makeovers in Movies". KQED. 2017-08-24. Archived from the original on 2020-02-27. Retrieved 2019-11-24.