Fugue

In music, a fugue (/fjuːɡ/) is a contrapuntal compositional technique in two or more voices, built on a subject (a musical theme) that is introduced at the beginning in imitation (repetition at different pitches) and which recurs frequently in the course of the composition. It is not to be confused with a fuguing tune, which is a style of song popularized by and mostly limited to early American (i.e. shape note or "Sacred Harp") music and West Gallery music. A fugue usually has three main sections: an exposition, a development and a final entry that contains the return of the subject in the fugue's tonic key. Some fugues have a recapitulation.[1]

In the Middle Ages, the term was widely used to denote any works in canonic style; by the Renaissance, it had come to denote specifically imitative works.[2] Since the 17th century,[3] the term fugue has described what is commonly regarded as the most fully developed procedure of imitative counterpoint.[4]

Most fugues open with a short main theme, the subject,[5] which then sounds successively in each voice (after the first voice is finished stating the subject, a second voice repeats the subject at a different pitch, and other voices repeat in the same way); when each voice has completed the subject, the exposition is complete. This is often followed by a connecting passage, or episode, developed from previously heard material; further "entries" of the subject then are heard in related keys. Episodes (if applicable) and entries are usually alternated until the "final entry" of the subject, by which point the music has returned to the opening key, or tonic, which is often followed by closing material, the coda.[6][7][8] In this sense, a fugue is a style of composition, rather than a fixed structure.

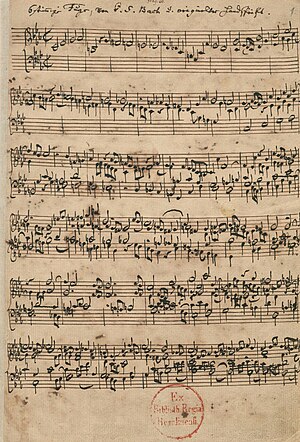

The form evolved during the 18th century from several earlier types of contrapuntal compositions, such as imitative ricercars, capriccios, canzonas, and fantasias.[9] The famous fugue composer Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) shaped his own works after those of Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck (1562-1621), Johann Jakob Froberger (1616–1667), Johann Pachelbel (1653–1706), Girolamo Frescobaldi (1583–1643), Dieterich Buxtehude (c. 1637–1707) and others.[9] With the decline of sophisticated styles at the end of the baroque period, the fugue's central role waned, eventually giving way as sonata form and the symphony orchestra rose to a dominant position.[10] Nevertheless, composers continued to write and study fugues for various purposes; they appear in the works of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791)[10] and Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827),[10] as well as modern composers such as Dmitri Shostakovich (1906–1975).[11]

Etymology

The English term fugue originated in the 16th century and is derived from the French word fugue or the Italian fuga. This in turn comes from Latin, also fuga, which is itself related to both fugere ("to flee") and fugare ("to chase").[12] The adjectival form is fugal.[13] Variants include fughetta (literally, "a small fugue") and fugato (a passage in fugal style within another work that is not a fugue).[6]

Musical outline

A fugue begins with the exposition and is written according to certain predefined rules; in later portions the composer has more freedom, though a logical key structure is usually followed. Further entries of the subject will occur throughout the fugue, repeating the accompanying material at the same time.[14] The various entries may or may not be separated by episodes.

What follows is a chart displaying a fairly typical fugal outline, and an explanation of the processes involved in creating this structure.

| Exposition | First mid-entry | Second mid-entry |

Final entries in tonic | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tonic | Dom. | T | (D-redundant entry) | Relative maj/min | Dom. of rel. | Subdom. | T | T | ||||||

| Soprano | S | CS1 | C o d e t t a |

CS2 | A | E p i s o d e |

CS1 | CS2 | E p i s o d e |

S | E p i s o d e |

CS1 | Free counterpoint |

C o d a |

| Alto | A | CS1 | CS2 | S | CS1 | CS2 | S | CS1 | ||||||

| Bass | S | CS1 | CS2 | A | CS1 | CS2 | S | |||||||

Exposition

A fugue begins with the exposition of its subject in one of the voices alone in the tonic key.[15] After the statement of the subject, a second voice enters and states the subject with the subject transposed to another key (usually the dominant or subdominant), which is known as the answer.[16][17] To make the music run smoothly, it may also have to be altered slightly. When the answer is an exact copy of the subject to the new key, with identical intervals to the first statement, it is classified as a real answer; if the intervals are altered to maintain the key it is a tonal answer.[15]

A tonal answer is usually called for when the subject begins with a prominent dominant note, or where there is a prominent dominant note very close to the beginning of the subject.[15] To prevent an undermining of the music's sense of key, this note is transposed up a fourth to the tonic rather than up a fifth to the supertonic. Answers in the subdominant are also employed for the same reason.[18]

While the answer is being stated, the voice in which the subject was previously heard continues with new material. If this new material is reused in later statements of the subject, it is called a countersubject; if this accompanying material is only heard once, it is simply referred to as free counterpoint.

The countersubject is written in invertible counterpoint at the octave or fifteenth.[19] The distinction is made between the use of free counterpoint and regular countersubjects accompanying the fugue subject/answer, because in order for a countersubject to be heard accompanying the subject in more than one instance, it must be capable of sounding correctly above or below the subject, and must be conceived, therefore, in invertible (double) counterpoint.[15][20]

In tonal music, invertible contrapuntal lines must be written according to certain rules because several intervallic combinations, while acceptable in one particular orientation, are no longer permissible when inverted. For example, when the note "G" sounds in one voice above the note "C" in lower voice, the interval of a fifth is formed, which is considered consonant and entirely acceptable. When this interval is inverted ("C" in the upper voice above "G" in the lower), it forms a fourth, considered a dissonance in tonal contrapuntal practice, and requires special treatment, or preparation and resolution, if it is to be used.[21] The countersubject, if sounding at the same time as the answer, is transposed to the pitch of the answer.[22] Each voice then responds with its own subject or answer, and further countersubjects or free counterpoint may be heard.

When a tonal answer is used, it is customary for the exposition to alternate subjects (S) with answers (A), however, in some fugues this order is occasionally varied: e.g., see the SAAS arrangement of Fugue No. 1 in C Major, BWV 846, from J.S. Bach's Well-Tempered Clavier, Book 1. A brief codetta is often heard connecting the various statements of the subject and answer. This allows the music to run smoothly. The codetta, just as the other parts of the exposition, can be used throughout the rest of the fugue.[23]

The first answer must occur as soon after the initial statement of the subject as possible; therefore the first codetta is often extremely short, or not needed. In the above example, this is the case: the subject finishes on the quarter note (or crotchet) B♭ of the third beat of the second bar which harmonizes the opening G of the answer. The later codettas may be considerably longer, and often serve to (a) develop the material heard so far in the subject/answer and countersubject and possibly introduce ideas heard in the second countersubject or free counterpoint that follows (b) delay, and therefore heighten the impact of the reentry of the subject in another voice as well as modulating back to the tonic.[24]

The exposition usually concludes when all voices have given a statement of the subject or answer. In some fugues, the exposition will end with a redundant entry, or an extra presentation of the theme.[15] Furthermore, in some fugues the entry of one of the voices may be reserved until later, for example in the pedals of an organ fugue (see J.S. Bach's Fugue in C major for Organ, BWV 547).

Episode

Further entries of the subject follow this initial exposition, either immediately (as for example in Fugue No. 1 in C major, BWV 846 of the Well-Tempered Clavier) or separated by episodes.[15] Episodic material is always modulatory and is usually based upon some element heard in the exposition.[7][15] Each episode has the primary function of transitioning for the next entry of the subject in a new key,[15] and may also provide release from the strictness of form employed in the exposition, and middle-entries.[25] André Gedalge states that the episode of the fugue is generally based on a series of imitations of the subject that have been fragmented.[26]

Development

Further entries of the subject, or middle entries, occur throughout the fugue. They must state the subject or answer at least once in its entirety, and may also be heard in combination with the countersubject(s) from the exposition, new countersubjects, free counterpoint, or any of these in combination. It is uncommon for the subject to enter alone in a single voice in the middle entries as in the exposition; rather, it is usually heard with at least one of the countersubjects and/or other free contrapuntal accompaniments.

Middle entries tend to occur at pitches other than the initial. As shown in the typical structure above, these are often closely related keys such as the relative dominant and subdominant, although the key structure of fugues varies greatly. In the fugues of J.S. Bach, the first middle entry occurs most often in the relative major or minor of the work's overall key, and is followed by an entry in the dominant of the relative major or minor when the fugue's subject requires a tonal answer. In the fugues of earlier composers (notably, Buxtehude and Pachelbel), middle entries in keys other than the tonic and dominant tend to be the exception, and non-modulation the norm. One of the famous examples of such non-modulating fugue occurs in Buxtehude's Praeludium (Fugue and Chaconne) in C, BuxWV 137.

When there is no entrance of the subject and answer material, the composer can develop the subject by altering the subject. This is called an episode,[27] often by inversion, although the term is sometimes used synonymously with middle entry and may also describe the exposition of completely new subjects, as in a double fugue for example (see below). In any of the entries within a fugue, the subject may be altered, by inversion, retrograde (a less common form where the entire subject is heard back-to-front) and diminution (the reduction of the subject's rhythmic values by a certain factor), augmentation (the increase of the subject's rhythmic values by a certain factor) or any combination of them.[15]

Example and analysis

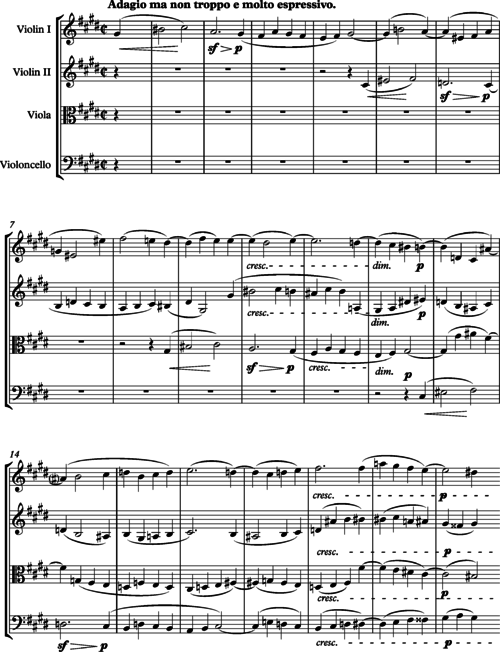

The excerpt below, bars 7–12 of J.S. Bach's Fugue No. 2 in C minor, BWV 847, from the Well-Tempered Clavier, Book 1 illustrates the application of most of the characteristics described above. The fugue is for keyboard and in three voices, with regular countersubjects.[7][28] This excerpt opens at last entry of the exposition: the subject is sounding in the bass, the first countersubject in the treble, while the middle-voice is stating a second version of the second countersubject, which concludes with the characteristic rhythm of the subject, and is always used together with the first version of the second countersubject. Following this an episode modulates from the tonic to the relative major by means of sequence, in the form of an accompanied canon at the fourth.[25] Arrival in E♭ major is marked by a quasi perfect cadence across the bar line, from the last quarter note beat of the first bar to the first beat of the second bar in the second system, and the first middle entry. Here, Bach has altered the second countersubject to accommodate the change of mode.[29]

False entries

At any point in the fugue there may be "false entries" of the subject, which include the start of the subject but are not completed. False entries are often abbreviated to the head of the subject, and anticipate the "true" entry of the subject, heightening the impact of the subject proper.[18]

Counter-exposition

The counter-exposition is a second exposition. However, there are only two entries, and the entries occur in reverse order.[30] The counter-exposition in a fugue is separated from the exposition by an episode and is in the same key as the original exposition.[30]

Stretto

Sometimes counter-expositions or the middle entries take place in stretto, whereby one voice responds with the subject/answer before the first voice has completed its entry of the subject/answer, usually increasing the intensity of the music.[31]

Only one entry of the subject must be heard in its completion in a stretto. However, a stretto in which the subject/answer is heard in completion in all voices is known as stretto maestrale or grand stretto.[32] Strettos may also occur by inversion, augmentation and diminution. A fugue in which the opening exposition takes place in stretto form is known as a close fugue or stretto fugue (see for example, the Gratias agimus tibi and Dona nobis pacem choruses from J.S. Bach's Mass in B Minor).[31]

Final entries and coda

The closing section of a fugue often includes one or two counter-expositions, and possibly a stretto, in the tonic; sometimes over a tonic or dominant pedal note. Any material that follows the final entry of the subject is considered to be the final coda and is normally cadential.[7]

Types

Simple fugue

A simple fugue has only one subject, and does not utilize invertible counterpoint.[33]

Double (triple, quadruple) fugue

A double fugue has two subjects that are often developed simultaneously. Similarly, a triple fugue has three subjects.[34][35] There are two kinds of double (triple) fugue: (a) a fugue in which the second (third) subject is (are) presented simultaneously with the subject in the exposition (e.g. as in Kyrie Eleison of Mozart's Requiem in D minor or the fugue of Bach's Passacaglia and Fugue in C minor, BWV 582), and (b) a fugue in which all subjects have their own expositions at some point, and they are not combined until later (see for example, the three-subject Fugue No. 14 in F♯ minor from Bach's Well-Tempered Clavier Book 2, or more famously, Bach's "St. Anne" Fugue in E♭ major, BWV 552, a triple fugue for organ.)[34][36]

Counter-fugue

A counter-fugue is a fugue in which the first answer is presented as the subject in inversion (upside down), and the inverted subject continues to feature prominently throughout the fugue.[37] Examples include Contrapunctus V through Contrapunctus VII, from Bach's The Art of Fugue.[38]

Permutation fugue

Permutation fugue describes a type of composition (or technique of composition) in which elements of fugue and strict canon are combined.[39] Each voice enters in succession with the subject, each entry alternating between tonic and dominant, and each voice, having stated the initial subject, continues by stating two or more themes (or countersubjects), which must be conceived in correct invertible counterpoint. (In other words, the subject and countersubjects must be capable of being played both above and below all the other themes without creating any unacceptable dissonances.) Each voice takes this pattern and states all the subjects/themes in the same order (and repeats the material when all the themes have been stated, sometimes after a rest).

There is usually very little non-structural/thematic material. During the course of a permutation fugue, it is quite uncommon, actually, for every single possible voice-combination (or "permutation") of the themes to be heard. This limitation exists in consequence of sheer proportionality: the more voices in a fugue, the greater the number of possible permutations. In consequence, composers exercise editorial judgment as to the most musical of permutations and processes leading thereto. One example of permutation fugue can be seen in the eighth and final chorus of J.S. Bach's cantata, Himmelskönig, sei willkommen, BWV 182.

Permutation fugues differ from conventional fugue in that there are no connecting episodes, nor statement of the themes in related keys.[39] So for example, the fugue of Bach's Passacaglia and Fugue in C minor, BWV 582 is not purely a permutation fugue, as it does have episodes between permutation expositions. Invertible counterpoint is essential to permutation fugues but is not found in simple fugues.[40]

Fughetta

A fughetta is a short fugue that has the same characteristics as a fugue. Often the contrapuntal writing is not strict, and the setting less formal. See for example, variation 24 of Beethoven's Diabelli Variations Op. 120.

History

Middle Ages and Renaissance

The term fuga was used as far back as the Middle Ages, but was initially used to refer to any kind of imitative counterpoint, including canons, which are now thought of as distinct from fugues.[41] Prior to the 16th century, fugue was originally a genre.[42] It was not until the 16th century that fugal technique as it is understood today began to be seen in pieces, both instrumental and vocal. Fugal writing is found in works such as fantasias, ricercares and canzonas.

"Fugue" as a theoretical term first occurred in 1330 when Jacobus of Liege wrote about the fuga in his Speculum musicae.[43] The fugue arose from the technique of "imitation", where the same musical material was repeated starting on a different note.

Gioseffo Zarlino, a composer, author, and theorist in the Renaissance, was one of the first to distinguish between the two types of imitative counterpoint: fugues and canons (which he called imitations).[42] Originally, this was to aid improvisation, but by the 1550s, it was considered a technique of composition. The composer Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina (1525?–1594) wrote masses using modal counterpoint and imitation, and fugal writing became the basis for writing motets as well.[44] Palestrina's imitative motets differed from fugues in that each phrase of the text had a different subject which was introduced and worked out separately, whereas a fugue continued working with the same subject or subjects throughout the entire length of the piece.

Baroque era

It was in the Baroque period that the writing of fugues became central to composition, in part as a demonstration of compositional expertise. Fugues were incorporated into a variety of musical forms. Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck, Girolamo Frescobaldi, Johann Jakob Froberger and Dieterich Buxtehude all wrote fugues,[45] and George Frideric Handel included them in many of his oratorios. Keyboard suites from this time often conclude with a fugal gigue. Domenico Scarlatti has only a few fugues among his corpus of over 500 harpsichord sonatas. The French overture featured a quick fugal section after a slow introduction. The second movement of a sonata da chiesa, as written by Arcangelo Corelli and others, was usually fugal.

The Baroque period also saw a rise in the importance of music theory. Some fugues during the Baroque period were pieces designed to teach contrapuntal technique to students.[46] The most influential text was Johann Joseph Fux's Gradus Ad Parnassum ("Steps to Parnassus"), which appeared in 1725.[47] This work laid out the terms of "species" of counterpoint, and offered a series of exercises to learn fugue writing.[48] Fux's work was largely based on the practice of Palestrina's modal fugues.[49] Mozart studied from this book, and it remained influential into the nineteenth century. Haydn, for example, taught counterpoint from his own summary of Fux and thought of it as the basis for formal structure.

Bach's most famous fugues are those for the harpsichord in The Well-Tempered Clavier, which many composers and theorists look at as the greatest model of fugue.[50] The Well-Tempered Clavier comprises two volumes written in different times of Bach's life, each comprising 24 prelude and fugue pairs, one for each major and minor key. Bach is also known for his organ fugues, which are usually preceded by a prelude or toccata. The Art of Fugue, BWV 1080, is a collection of fugues (and four canons) on a single theme that is gradually transformed as the cycle progresses. Bach also wrote smaller single fugues and put fugal sections or movements into many of his more general works. J.S. Bach's influence extended forward through his son C.P.E. Bach and through the theorist Friedrich Wilhelm Marpurg (1718–1795) whose Abhandlung von der Fuge ("Treatise on the fugue", 1753) was largely based on J.S. Bach's work.

Classical era

During the Classical era, the fugue was no longer a central or even fully natural mode of musical composition.[51] Nevertheless, both Haydn and Mozart had periods of their careers in which they in some sense "rediscovered" fugal writing and used it frequently in their work.

Haydn

Joseph Haydn was the leader of fugal composition and technique in the Classical era.[4] Haydn's most famous fugues can be found in his "Sun" Quartets (op. 20, 1772), of which three have fugal finales. This was a practice that Haydn repeated only once later in his quartet-writing career, with the finale of his String Quartet, Op. 50 No. 4 (1787). Some of the earliest examples of Haydn's use of counterpoint, however, are in three symphonies (No. 3, No. 13, and No. 40) that date from 1762 to 1763. The earliest fugues, in both the symphonies and in the Baryton trios, exhibit the influence of Joseph Fux's treatise on counterpoint, Gradus ad Parnassum (1725), which Haydn studied carefully.

Haydn's second fugal period occurred after he heard, and was greatly inspired by, the oratorios of Handel during his visits to London (1791–1793, 1794–1795). Haydn then studied Handel's techniques and incorporated Handelian fugal writing into the choruses of his mature oratorios The Creation and The Seasons, as well as several of his later symphonies, including No. 88, No. 95, and No. 101; and the late string quartets, Opus 71 no. 3 and (especially) Opus 76 no. 6.

Mozart

The young Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart studied counterpoint with Padre Martini in Bologna. Under the employment of Archbishop Colloredo, and the musical influence of his predecessors and colleagues such as Johann Ernst Eberlin, Anton Cajetan Adlgasser, Michael Haydn, and his own father, Leopold Mozart at the Salzburg Cathedral, the young Mozart composed ambitious fugues and contrapuntal passages in Catholic choral works such as Mass in C minor, K. 139 "Waisenhaus" (1768), Mass in C major, K. 66 "Dominicus" (1769), Mass in C major, K. 167 "in honorem Sanctissimae Trinitatis" (1773), Mass in C major, K. 262 "Missa longa" (1775), Mass in C major, K. 337 "Solemnis" (1780), various litanies, and vespers. Leopold admonished his son openly in 1777 that he not forget to make public demonstration of his abilities in "fugue, canon, and contrapunctus".[52] Later in life, the major impetus to fugal writing for Mozart was the influence of Baron Gottfried van Swieten in Vienna around 1782. Van Swieten, during diplomatic service in Berlin, had taken the opportunity to collect as many manuscripts by Bach and Handel as he could, and he invited Mozart to study his collection and encouraged him to transcribe various works for other combinations of instruments. Mozart was evidently fascinated by these works and wrote a set of five transcriptions for string quartet, K. 405 (1782), of fugues from Bach's Well-Tempered Clavier, introducing them with preludes of his own. In a letter to his sister Nannerl Mozart, dated in Vienna on 20 April 1782, Mozart recognizes that he had not written anything in this form, but moved by his wife's interest he composed one piece, which is sent with the letter. He begs her not to let anybody see the fugue and manifests the hope to write five more and then present them to Baron van Swieten. Regarding the piece, he said "I have taken particular care to write andante maestoso upon it, so that it should not be played fast – for if a fugue is not played slowly the ear cannot clearly distinguish the new subject as it is introduced and the effect is missed".[53] Mozart then set to writing fugues on his own, mimicking the Baroque style. These included a fugue in C minor, K. 426, for two pianos (1783). Later, Mozart incorporated fugal writing into his opera Die Zauberflöte and the finale of his Symphony No. 41.

The parts of the Requiem he completed also contain several fugues (most notably the Kyrie, and the three fugues in the Domine Jesu;[54] he also left behind a sketch for an Amen fugue which, some believe[who?], would have come at the end of the Sequentia).

Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven was familiar with fugal writing from childhood, as an important part of his training was playing from The Well-Tempered Clavier. During his early career in Vienna, Beethoven attracted notice for his performance of these fugues. There are fugal sections in Beethoven's early piano sonatas, and fugal writing is to be found in the second and fourth movements of the Eroica Symphony (1805). Beethoven incorporated fugues in his sonatas, and reshaped the episode's purpose and compositional technique for later generations of composers.[55]

Nevertheless, fugues did not take on a truly central role in Beethoven's work until his late period. The finale of Beethoven's Hammerklavier Sonata contains a fugue, which was practically unperformed until the late 19th century, due to its tremendous technical difficulty and length. The last movement of his Cello Sonata, Op. 102 No. 2 is a fugue, and there are fugal passages in the last movements of his Piano Sonatas in A major, Op. 101 and A♭ major Op. 110. According to Charles Rosen, "With the finale of 110, Beethoven re-conceived the significance of the most traditional elements of fugue writing."[56]

Fugal passages are also found in the Missa Solemnis and all movements of the Ninth Symphony, except the third. A massive, dissonant fugue forms the finale of his String Quartet, Op. 130 (1825); the latter was later published separately as Op. 133, the Große Fuge ("Great Fugue"). However, it is the fugue that opens Beethoven's String Quartet in C♯ minor, Op. 131 that several commentators regard as one of the composer's greatest achievements. Joseph Kerman (1966, p. 330) calls it "this most moving of all fugues".[57] J. W. N. Sullivan (1927, p. 235) hears it as "the most superhuman piece of music that Beethoven has ever written."[58] Philip Radcliffe (1965, p. 149) says "[a] bare description of its formal outline can give but little idea of the extraordinary profundity of this fugue ."[59]

Romantic era

By the beginning of the Romantic era, fugue writing had become specifically attached to the norms and styles of the Baroque. Felix Mendelssohn wrote many fugues inspired by his study of the music of Johann Sebastian Bach.

Johannes Brahms' Variations and Fugue on a Theme by Handel, Op. 24, is a work for solo piano written in 1861. It consists of a set of twenty-five variations and a concluding fugue, all based on a theme from George Frideric Handel's Harpsichord Suite No. 1 in B♭ major, HWV 434.

Franz Liszt's Piano Sonata in B minor (1853) contains a powerful fugue, demanding incisive virtuosity from its player:

Richard Wagner included several fugues in his opera Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg. Giuseppe Verdi included a whimsical example at the end of his opera Falstaff[60] and his setting of the Requiem Mass contained two (originally three) choral fugues.[61] Anton Bruckner and Gustav Mahler also included them in their respective symphonies. The exposition of the finale of Bruckner's Symphony No. 5 begins with a fugal exposition. The exposition ends with a chorale, the melody of which is then used as a second fugal exposition at the beginning of the development. The recapitulation features both fugal subjects concurrently.[citation needed] The finale of Mahler's Symphony No. 5 features a "fugue-like"[62] passage early in the movement, though this is not actually an example of a fugue.

20th century

Twentieth-century composers brought fugue back to its position of prominence, realizing its uses in full instrumental works, its importance in development and introductory sections, and the developmental capabilities of fugal composition.[51]

The second movement of Maurice Ravel's piano suite Le Tombeau de Couperin (1917) is a fugue that Roy Howat (200, p. 88) describes as having "a subtle glint of jazz".[63] Béla Bartók's Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta (1936) opens with a slow fugue that Pierre Boulez (1986, pp. 346–47) regards as "certainly the finest and most characteristic example of Bartók's subtle style... probably the most timeless of all Bartók's works – a fugue that unfolds like a fan to a point of maximum intensity and then closes, returning to the mysterious atmosphere of the opening."[64] The second movement of Bartók‘s Sonata for Solo Violin is a fugue, and the first movement of his Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion contains a fugato.

Schwanda the Bagpiper (Czech: Švanda dudák), written in 1926, an opera in two acts (five scenes), with music by Jaromír Weinberger, includes a Polka followed by a powerful Fugue based on the Polka theme.

Igor Stravinsky also incorporated fugues into his works, including the Symphony of Psalms and the Dumbarton Oaks concerto. Stravinsky recognized the compositional techniques of Bach, and in the second movement of his Symphony of Psalms (1930), he lays out a fugue that is much like that of the Baroque era.[65] It employs a double fugue with two distinct subjects, the first beginning in C and the second in E♭. Techniques such as stretto, sequencing, and the use of subject incipits are frequently heard in the movement. Dmitri Shostakovich's 24 Preludes and Fugues is the composer's homage to Bach's two volumes of The Well-Tempered Clavier. In the first movement of his Fourth Symphony, starting at rehearsal mark 63, is a gigantic fugue in which the 20-bar subject (and tonal answer) consist entirely of semiquavers, played at the speed of quaver = 168.

Olivier Messiaen, writing about his Vingt regards sur l'enfant-Jésus (1944) wrote of the sixth piece of that collection, "Par Lui tout a été fait" ("By Him were all things made"):

It expresses the Creation of All Things: space, time, stars, planets – and the Countenance (or rather, the Thought) of God behind the flames and the seething – impossible even to speak of it, I have not attempted to describe it ... Instead, I have sheltered behind the form of the Fugue. Bach's Art of Fugue and the fugue from Beethoven's Opus 106 (the Hammerklavier sonata) have nothing to do with the academic fugue. Like those great models, this one is an anti-scholastic fugue.[66]

György Ligeti wrote a five-part double fugue[clarification needed] for his Requiem's second movement, the Kyrie, in which each part (SMATB) is subdivided in four-voice "bundles" that make a canon.[failed verification] The melodic material in this fugue is totally chromatic, with melismatic (running) parts overlaid onto skipping intervals, and use of polyrhythm (multiple simultaneous subdivisions of the measure), blurring everything both harmonically and rhythmically so as to create an aural aggregate, thus highlighting the theoretical/aesthetic question of the next section as to whether fugue is a form or a texture.[67] According to Tom Service, in this work, Ligeti

takes the logic of the fugal idea and creates something that’s meticulously built on precise contrapuntal principles of imitation and fugality, but he expands them into a different region of musical experience. Ligeti doesn’t want us to hear individual entries of the subject or any subject, or to allow us access to the labyrinth through listening in to individual lines… He creates instead a vastly dense texture of voices in his choir and orchestra, a huge stratified slab of terrifying visionary power. Yet this is music that’s made with a fine craft and detail of a Swiss clock maker. Ligeti’s so-called 'micro-polyphony': the many voicedness of small intervals at small distances in time from one another is a kind of conjuring trick. At the micro level of the individual lines, and there are dozens and dozens of them in this music...there’s an astonishing detail and finesse, but the overall macro effect is a huge overwhelming and singular experience.[68]

Benjamin Britten used a fugue in the final part of The Young Person's Guide to the Orchestra (1946). The Henry Purcell theme is triumphantly cited at the end, making it a choral fugue.[69]

Canadian pianist and musical thinker Glenn Gould composed So You Want to Write a Fugue?, a full-scale fugue set to a text that cleverly explicates its own musical form.[70]

Outside classical music

Fugues (or fughettas/fugatos) have been incorporated into genres outside Western classical music. Several examples exist within jazz, such as Bach goes to Town, composed by the Welsh composer Alec Templeton and recorded by Benny Goodman in 1938, and Concorde composed by John Lewis and recorded by the Modern Jazz Quartet in 1955.

In "Fugue for Tinhorns" from the Broadway musical Guys and Dolls, written by Frank Loesser, the characters Nicely-Nicely, Benny, and Rusty sing simultaneously about hot tips they each have in an upcoming horse race. [71]

In "West Side Story", the dance sequence following the song "Cool" is structured as a fugue. Interestingly, Leonard Bernstein quotes Beethoven's monumental "Große Fuge" for string quartet and employs Arnold Schoenberg's twelve tone technique, all in the context of a jazz infused Broadway show stopper.

A few examples also exist within progressive rock, such as the central movement of "The Endless Enigma" by Emerson, Lake & Palmer and "On Reflection" by Gentle Giant.

On their EP of the same name, Vulfpeck has a composition called "Fugue State", which incorporates a fugue between Theo Katzman (guitar), Joe Dart (bass), and Woody Goss (Wurlitzer keyboard).

The composer Matyas Seiber included an atonal or twelve-tone fugue, for flute trumpet and string quartet, in his score for the 1953 film Graham Sutherland[72]

The film composer John Williams includes a fugue in his score for the 1990 film, Home Alone, at the point where Kevin, accidentally left at home by his family, and realizing he is about to be attacked by a pair of bumbling burglars, begins to plan his elaborate defenses. Another fugue occurs at a similar point in the 1992 sequel film, Home Alone 2: Lost in New York.

The jazz composer and film composer, Michel Legrand, includes a fugue as the climax of his score (a classical theme with variations, and fugue) for Joseph Losey's 1972 film The Go-Between, based on the 1953 novel by British novelist, L.P. Hartley, as well as several times in his score for Jacques Demy's 1970 film Peau d'âne.

Discussion

Musical form or texture

A widespread view of the fugue is that it is not a musical form but rather a technique of composition.[73]

The Austrian musicologist Erwin Ratz argues that the formal organization of a fugue involves not only the arrangement of its theme and episodes, but also its harmonic structure.[74] In particular, the exposition and coda tend to emphasize the tonic key, whereas the episodes usually explore more distant tonalities. Ratz stressed, however, that this is the core, underlying form ("Urform") of the fugue, from which individual fugues may deviate.

Although certain related keys are more commonly explored in fugal development, the overall structure of a fugue does not limit its harmonic structure. For example, a fugue may not even explore the dominant, one of the most closely related keys to the tonic. Bach's Fugue in B♭ major from Book 1 of the Well Tempered Clavier explores the relative minor, the supertonic and the subdominant. This is unlike later forms such as the sonata, which clearly prescribes which keys are explored (typically the tonic and dominant in an ABA form). Then, many modern fugues dispense with traditional tonal harmonic scaffolding altogether, and either use serial (pitch-oriented) rules, or (as the Kyrie/Christe in György Ligeti's Requiem, Witold Lutosławski works), use panchromatic, or even denser, harmonic spectra.

Perceptions and aesthetics

The fugue is the most complex of contrapuntal forms. In Ratz's words, "fugal technique significantly burdens the shaping of musical ideas, and it was given only to the greatest geniuses, such as Bach and Beethoven, to breathe life into such an unwieldy form and make it the bearer of the highest thoughts."[75] In presenting Bach's fugues as among the greatest of contrapuntal works, Peter Kivy points out that "counterpoint itself, since time out of mind, has been associated in the thinking of musicians with the profound and the serious"[76] and argues that "there seems to be some rational justification for their doing so."[77]

This is related to the idea that restrictions create freedom for the composer, by directing their efforts. He also points out that fugal writing has its roots in improvisation, and was, during the Renaissance, practiced as an improvisatory art. Writing in 1555, Nicola Vicentino, for example, suggests that:

the composer, having completed the initial imitative entrances, take the passage which has served as accompaniment to the theme and make it the basis for new imitative treatment, so that "he will always have material with which to compose without having to stop and reflect". This formulation of the basic rule for fugal improvisation anticipates later sixteenth-century discussions which deal with the improvisational technique at the keyboard more extensively.[78]

References

- ^ Benward, Bruce (1985). Music in Theory and Practice. Vol. 2 (3rd ed.). Dubuque: Wm. C. Brown Publishers. p. 45. ISBN 0-697-03633-2.

- ^ "Fugue [Fr. fugue; Ger. Fuge; Lat., It., Sp., fuga]." The Harvard Dictionary of Music (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2003), "credo Reference". Retrieved 6 May 2008.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Walker, Paul (2001). "Fugue". In Sadie, Stanley; Tyrrell, John (eds.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 978-1-56159-239-5. for discussion of the changing use of the term throughout Western music history.

- ^ a b Ratner 1980, p. 263

- ^ Gedalge 1964, p. 7

- ^ a b "Fugue", The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Music, fourth edition, ed. Michael Kennedy (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1996). ISBN 0-19-280037-X Kennedy, Michael; Kennedy, Joyce Bourne; Bourne, Joyce (2007). Oxford Reference Online, subscription access. ISBN 978-0-19-920383-3. Retrieved 16 March 2007.

- ^ a b c d Walker, Paul (2001). "Fugue, §1: A classic fugue analysed". In Sadie, Stanley; Tyrrell, John (eds.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 978-1-56159-239-5.

- ^ "Fugue | music". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

- ^ a b Walker, Paul (2001). "Fugue". In Sadie, Stanley; Tyrrell, John (eds.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 978-1-56159-239-5.

- ^ a b c Walker, Paul (2001). "Fugue, §6: Late 18th century". In Sadie, Stanley; Tyrrell, John (eds.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 978-1-56159-239-5.

- ^ Walker, Paul (2001). "Fugue, §8: 20th century". In Sadie, Stanley; Tyrrell, John (eds.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 978-1-56159-239-5.

- ^ "Fugue, n." The Concise Oxford English Dictionary, eleventh edition, revised, ed. Catherine Soanes and Angus Stevenson (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2006). "Oxford Reference Online, subscription access". Retrieved 16 March 2007.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Fugal, adj." The Concise Oxford English Dictionary, eleventh edition, revised, ed. Catherine Soanes and Angus Stevenson (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2006). "Oxford Reference Online, subscription access". Retrieved 16 March 2007.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Gedalge 1964, p. 70

- ^ a b c d e f g h i G. M. Tucker and Andrew V. Jones, "Fugue", in The Oxford Companion to Music, ed. Alison Latham (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2002). ISBN 0-19-866212-2 Latham, Alison (2011). Oxford Reference Online, subscription access. ISBN 978-0-19-957903-7. Retrieved 16 March 2007.

- ^ Gedalge 1964, p. 12

- ^ Morris, R. O. (1958). Contrapuntal Technique in the Sixteenth Century. London: Oxford University Press. p. 47.

- ^ a b Verrall 1966, p. 12

- ^ Gedalge 1964, p. 59

- ^ "Invertible Counterpoint" The Oxford Companion to Music, ed. Alison Latham (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2002) Latham, Alison (2011). Oxford Reference Online, subscription access. ISBN 978-0-19-957903-7. Retrieved 16 March 2007.

- ^ Drabkin, William (2001). "Invertible Counterpoint". In Sadie, Stanley; Tyrrell, John (eds.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 978-1-56159-239-5.

- ^ Gedalge 1964, p. 61

- ^ Gedalge 1964, pp. 71–72

- ^ Paul Walker, "Fugue, §1: A Classic Fugue Analysed" "Grove Music Online". Retrieved 18 February 2007.

- ^ a b Verrall 1966, p. 33

- ^ Gedalge 1964

- ^ Walker, Paul (2001). "Counter-exposition". In Sadie, Stanley; Tyrrell, John (eds.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 978-1-56159-239-5.

- ^ Bach, Johann Sebastian (1997). "Fuge Nr. 2". In Heinemann, Ernst-Günter (ed.). Das Wohltemperierte Klavier I. Munich: G. Henle Verlag.

- ^ Dreyfus, Laurence (1996). "Figments of the Organicist Imagination". Bach and the Patterns of Invention. Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London: Harvard University Press. p. 178.

- ^ a b Gedalge 1964, p. 108

- ^ a b Walker, Paul (2001). "Stretto (i)". In Sadie, Stanley; Tyrrell, John (eds.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 978-1-56159-239-5.

- ^ Verrall 1966, p. 77

- ^ Walker, Paul (2001). "Fugue, §5: The golden age". In Sadie, Stanley; Tyrrell, John (eds.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 978-1-56159-239-5.

- ^ a b Walker, Paul (2001). "Double Fugue". In Sadie, Stanley; Tyrrell, John (eds.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 978-1-56159-239-5.

- ^ "double fugue" The Oxford Companion to Music, Ed. Alison Latham, Oxford University Press, 2002, Latham, Alison (2011). Oxford Reference Online, subscription access. ISBN 978-0-19-957903-7. Retrieved 29 March 2007.

- ^ "Double Fugue", The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Music, fourth edition, ed. Michael Kennedy (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1996) Kennedy, Michael; Kennedy, Joyce Bourne; Bourne, Joyce (2007). Oxford Reference Online, subscription access. ISBN 978-0-19-920383-3. Retrieved 29 March 2007.

- ^ Walker, Paul (2001). "Counter-fugue". In Sadie, Stanley; Tyrrell, John (eds.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 978-1-56159-239-5.

- ^ Bach, Johann Sebastian (1992). Dörffel, Alfred (ed.). The Art of Fugue & A Musical Offering. Courier Dover. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-486-27006-7.

- ^ a b Walker, Paul (2001). "Permutation Fugue". In Sadie, Stanley; Tyrrell, John (eds.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 978-1-56159-239-5.

- ^ Walker 1992, p. 56

- ^ Walker 2000, p. 7

- ^ a b Walker 2000, pp. 9–10

- ^ Mann 1960, p. 9

- ^ Perkins, Leeman L. (1999). Music in the Age of the Renaissance. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 880–81.

- ^ Walker 2000, p. 165

- ^ Schulenberg, David (2001). Music of the Baroque. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 243.

- ^ Walker 2000, p. 316

- ^ Walker 2000, p. 317

- ^ Mann 1960, p. 53

- ^ Walker 2000, p. 2

- ^ a b Graves 1962, p. 64

- ^ Ulrich Konrad (2008). "On ancient languages: the historical idiom in the music of Wolfgang Amadé Mozart" (PDF). In Thomas Forrest Kelly; Sean Gallagher (eds.). The Century of Bach & Mozart. Translated by Thomas Irvine (this chapter). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Department of Music. p. 236. ISBN 9780964031739.

- ^ Letters of Mozart. New York: Dorset Press. 1986. p. 195.[full citation needed]

- ^ Ratner 1980, p. 266

- ^ Graves 1962, p. 65

- ^ Rosen, Charles (1971) The Classical Style, p. 501. London, Faber.

- ^ Kerman, Joseph (1966), The Beethoven Quartets. Oxford University Press

- ^ Sullivan, J. W. N. (1927) Beethoven. London, Jonathan Cape

- ^ Radcliffe, P. (1965) Beethoven's String Quartets. London, Hutchinson.

- ^ Shaw, Bernard (1978). The Great Composers: Reviews and Bombardments. University of California Press. p. 223. ISBN 978-0-520-03266-8.

- ^ Budden, Julian (December 2015). Verdi. Oxford University Press. p. 340. ISBN 978-0-19-027398-9.

- ^ Floros, Constantin. (1997, p. 135) Gustav Mahler: The Symphonies, trans. Wicker. Amadeus Press.

- ^ Howat, R. (2000) "Ravel and the Piano" in Mawer, D. (ed.) The Cambridge Companion to Ravel. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Boulez, P. (1986) Orientations. London, Faber.

- ^ Graves 1962, p. 67

- ^ Notes to Vingt Regards sur l'Enfant Jésus. Translator not indicated. Erato Disques S.A. 4509-91705-2, 1993. Compact Disc.

- ^ Eric Drott, "Lines, Masses, Micropolyphony: Ligeti's Kyrie and the 'Crisis of the Figure' ". Perspectives of New Music 49, no. 1 (Winter 2011): 4–46. Citation on 10.

- ^ Service, Tom. (26 November 2017) "Chasing a Fugue", BBC Radio 3

- ^ "Listening to Britten – the Young Person's Guide to the Orchestra, Op.34". 18 October 2013.

- ^ Bazzana, Kevin (2004). Wondrous Strange: The Life and Art of Glenn Gould. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-517440-2. OCLC 54687539.

- ^ "Fugue for Tinhorns - Guys and Dolls (1955) - YouTube". YouTube.

- ^ Keller, Hans (2006). Film Music and Beyond. London: Plumbago Books. p. 167.

- ^ Tovey, Donald Francis (1962). Essays in Music Analysis Volume I: Symphonies. London: Oxford University Press. p. 17.

- ^ Ratz 1951, Chapter 3

- ^ Ratz 1951, p. 259

- ^ Kivy 1990, p. 206

- ^ Kivy 1990, p. 210

- ^ Mann 1965, p. 16

Sources

- Gedalge, André (1964) [1901]. Traité de la fugue [Treatise on Fugue]. trans. A. Levin. Mattapan: Gamut Music Company. OCLC 917101.

- Graves, William L. Jr. (1962). Twentieth Century Fugue. Washington, D.C.: The Catholic University of America Press. OCLC 480340.

- Kivy, Peter (1990). Music Alone: Philosophical Reflections on the Purely Musical Experience. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-2331-7.

- Mann, Alfred (1960). The Study of Fugue. London: Oxford University Press.

- Mann, Alfred (1965). The Study of Fugue. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

- Ratner, Leonard G. (1980). Classic Music: Expression, Form, and Style. London: Collier Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 9780028720203. OCLC 6648908.

- Ratz, Erwin (1951). Einführung in die Musikalische Formenlehre: Über Formprinzipien in den Inventionen J. S. Bachs und ihre Bedeutung für die Kompositionstechnik Beethovens [Introduction to Musical Form: On the Principles of Form in J. S. Bach's Inventions and their Import for Beethoven's Compositional Technique] (first edition with supplementary volume). Vienna: Österreichischer Bundesverlag für Unterricht, Wissenschaft und Kunst.

- Verrall, John W. (1966). Fugue and Invention in Theory and Practice. Palo Alto: Pacific Books. OCLC 1173554.

- Walker, Paul (1992). The Origin of Permutation Fugue. New York: Broude Brothers Limited.

- Walker, Paul Mark (2000). Theories of Fugue from the Age of Josquin to the Age of Bach. Eastman studies in music. Vol. 13. Rochester: University of Rochester Press. ISBN 9781580461504. OCLC 56634238.

Further reading

- Horsley, Imogene (1966). Fugue: History and Practice. New York/London: Free Press/Collier-Macmillan.

- Kerman, Joseph (2015). The Art of Fugue: Bach Fugues for Keyboard, 1715–1750. University of California Press. doi:10.1525/luminos.1. ISBN 9780520962590.

External links

- Score Archived 7 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine, J. S. Bach's The Well-Tempered Clavier, Mutopia Project

- Fugues of the Well-Tempered Clavier (viewable in Adobe Flash Archived 25 February 2019 at the Wayback Machine or Shockwave)

- Theory on fugues

- Fugues and fugue sets

- Analyses of J. S. Bach's Well-Tempered Clavier with accompanying recordings

- . The American Cyclopædia. 1879.

- Visualization of Bach's "Little" Fugue in G minor, organ on YouTube

- Analyses of J. S. Bach's Fugue for Solo Violin in C major, BWV 1005 (tutorial video with score) on YouTube