Becker muscular dystrophy

| Becker muscular dystrophy | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Benign pseudohypertrophic muscular dystrophy[1] |

| |

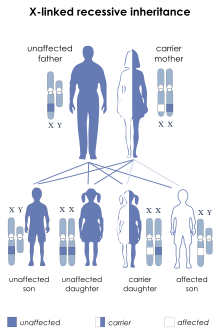

| X-linked recessive is the manner in which this condition is inherited | |

| Specialty | Neurology |

| Symptoms | Severe upper extremity muscle weakness,[2] Toe-walking[3] |

| Causes | Mutations in DMD gene[4] |

| Diagnostic method | Neurological exam, muscle exam[3] |

| Treatment | No current cure, Physical therapy [3] |

Becker muscular dystrophy (BMD) is an X-linked recessive inherited disorder characterized by slowly progressing muscle weakness of the legs and pelvis. It is a type of dystrophinopathy.[5][3] This is caused by mutations in the dystrophin gene, which encodes the protein dystrophin. Becker muscular dystrophy is related to Duchenne muscular dystrophy in that both result from a mutation in the dystrophin gene,[4] but has a milder course.[6][7]

Signs and symptoms

Some symptoms consistent with Becker muscular dystrophy are:

- Muscle weakness, gradually increasing difficulty with walking[2]

- Severe upper extremity muscle weakness[2]

- Toe-walking[3]

- Use of Gower's Maneuver to get up from floor[8]

- Difficulty breathing[3]

- Skeletal deformities of the chest, and back (scoliosis)[3]

- Pseudohypertrophy of calf muscles[2]

- Muscle cramps[2]

- Heart muscle problems[2]

- Elevated creatine kinase levels in blood[2]

Individuals with this disorder typically experience progressive muscle weakness of the leg and pelvis muscles, which is associated with a loss of muscle mass (wasting). Muscle weakness also occurs in the arms, neck, and other areas, but not as noticeably severe as in the lower half of the body. Calf muscles initially enlarge during the ages of 5-15 (an attempt by the body to compensate for loss of muscle strength), but the enlarged muscle tissue is eventually replaced by fat and connective tissue (pseudohypertrophy) as the legs become less used (with use of wheelchair).[medical citation needed]

Complications

Possible complications associated with muscular dystrophies (MD) are cardiac arrhythmias.[9] Becker muscular dystrophy (BMD) also demonstrates the following:

- Mental impairment (less common in BMD than in DMD)[10]

- Pulmonary failure[3]

- Pneumonia[3]

Genetics

The gene affected is the DMD gene, is located on the X chromosome and is inherited in an X-linked recessive pattern.[11] Since women have two X chromosomes, if one X chromosome has the non-working gene, the second X chromosome will have a working copy of the gene to compensate, because of this ability to compensate, women rarely develop symptoms. All dystrophinopathies are inherited in an X-linked recessive manner. The risk to the siblings of an affected individual depends upon the carrier status of the mother. Carrier females have a 50% chance of passing the DMD mutation in each pregnancy. Sons who inherit the mutation will be affected; daughters who inherit the mutation will be carriers. Men who have Becker muscular dystrophy can have children, and all their daughters are carriers, but none of the sons will inherit their father's mutation.[10][12][13]

The DMD gene can be broken down into four different regions: the N terminal, rod, cysteine-rich, and carboxy terminal.[11] This is the largest gene/protein in the human body, and due to its size, can have many different mutations affecting it and therefore differing clinical presentations.[citation needed]For example some patients with Becker's can be asymptomatic aside from blood work abnormalities, and some can present with progressive muscle weakness, heart defects, and difficulty with activities of daily living.[citation needed]Some literature even describes unique cases where muscle pain, cramping, and elevated creatine kinase levels are the only presenting symptoms instead of the classic presentation of muscle weakness.[14]

Becker muscular dystrophy occurs in approximately 1.5 to 6 in 100,000 male births, making it much less common than Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Symptoms usually appear in men at about ages 8–25, but may sometimes begin later.[15] Genetic counseling may be advisable when potential carriers or patients want to have children. Sons of a man with Becker muscular dystrophy do not develop the disorder, but daughters will be carriers (and some carriers can experience some symptoms of muscular dystrophy), so the daughters' sons may develop the disorder.[16]

Diagnosis

In terms of the diagnosis of Becker muscular dystrophy symptom development resembles that of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. A physical exam indicates lack of pectoral and upper arm muscles, especially when the disease is unnoticed through the early teen years. Muscle wasting begins in the legs and pelvis, then progresses to the muscles of the shoulders and neck. Calf muscle enlargement (pseudohypertrophy) is quite obvious. Among the exams/tests performed are:[17][18]

- Muscle biopsy (removes a small piece of muscle tissue, usually from the thigh, to check for dystrophin in muscle cells.)

- Creatine kinase test (checks the level of Creatine Kinase proteins in the blood. Creatine Kinase proteins are normally found inside of healthy muscle cells, but can be found in the blood when muscle cells are damaged.)

- Electromyography (shows that weakness is caused by destruction of muscle tissue rather than by damage to nerves.)

- Genetic testing (looks for deletion, duplication, or mutation of the dystrophin gene.)

Treatment

There is no known cure for Becker muscular dystrophy yet. Treatment is aimed at control of symptoms to maximize the quality of life which can be measured by specific questionnaires.[19] Activity is encouraged and can be considered vital for long term survivability for these patients.[20] Inactivity (such as bed rest) or sitting down for too long can worsen the muscle disease. Physical therapy may be helpful to maintain muscle strength. Orthopedic appliances such as braces and wheelchairs may improve mobility and self-care.[12]

Immunosuppressant steroids have been known to help slow the progression of Becker muscular dystrophy.[21] The drug prednisone contributes to an increased production of the protein utrophin which closely resembles dystrophin, the protein that is defective in BMD.[22]

The cardiac problems that occur with EDMD and myotonic muscular dystrophy may require a pacemaker.[23] Other cardiomyopathy seen in Beckers can also be treated with ACE-inhibitors, cardiac transplant, and other personalized treatment.[20]

The investigational drug Debio-025 is a known inhibitor of the protein cyclophilin D, which regulates the swelling of mitochondria in response to cellular injury. Researchers decided to test the drug in mice engineered to carry MD after earlier laboratory tests showed deleting a gene that encodes cyclophilin D reduced swelling and reversed or prevented the disease's muscle-damaging characteristics.[24] According to a review by Bushby, et al. if a primary protein is not functioning properly then maybe another protein could take its place by augmenting it. Upregulation of compensatory proteins has been done in models of transgenic mice.[25]

Prognosis

The progression of Becker muscular dystrophy is highly variable—much more so than Duchenne muscular dystrophy. There is also a form that may be considered as an intermediate between Duchenne and Becker MD (mild DMD or severe BMD). Severity of the disease may be indicated by age of the patient at the onset of the disease. One study showed that there may be two distinct patterns of progression in Becker muscular dystrophy. Onset at around age 7 to 8 years of age shows more cardiac involvement and trouble climbing stairs by age 20, if onset is around age 12, there is less cardiac involvement.[17][26]

The quality of life for patients with Becker muscular dystrophy can be impacted by the symptoms of the disorder. But with assistive devices, independence can be maintained. People affected by Becker muscular dystrophy can still maintain active lifestyles.[27]

Research

There is no cure for any type of muscular dystrophy group.[28] Several drugs designed to address the root cause are under development, including gene therapy (Microdystrophin), and antisense drugs (Ataluren, Eteplirsen etc.).[29] Other medications used include corticosteroids (Deflazacort), calcium channel blockers (Diltiazem) to slow skeletal and cardiac muscle degeneration, anticonvulsants to control seizures and some muscle activity, and immunosuppressants (Vamorolone) to delay damage to dying muscle cells.[30] Physical therapy, braces, and corrective surgery may help with some symptoms[30] while assisted ventilation may be required in those with weakness of breathing muscles.[31] Outcomes depend on the specific type of disorder.[30][29]

History

Becker muscular dystrophy is named after the German doctor Peter Emil Becker who published an article about it in 1955.[32][33]

References

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- ^ "Becker muscular dystrophy: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Becker's Muscular Dystrophy information. Patient". 12 June 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Becker muscular dystrophy". NIH. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- ^ a b "Becker muscular dystrophy | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program". Archived from the original on 2016-04-28. Retrieved 2016-04-19.

- ^ "Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophy". NIH.gov. NIH. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- ^ Aslesh, Tejal; Maruyama, Rika; Yokota, Toshifumi (2018-01-02). "Skipping Multiple Exons to Treat DMD—Promises and Challenges". Biomedicines. 6 (1): 1. doi:10.3390/biomedicines6010001. ISSN 2227-9059. PMC 5874658. PMID 29301272.

- ^ "Muscular Dystrophy, Becker". NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). Retrieved 2021-04-17.

- ^ Greco, Giovanni N. (2008). Tissue Engineering Research Trends. Nova Publishers. p. 89. ISBN 9781604562644. Retrieved 19 April 2016.

- ^ "Cardiovascular Complications Associated with Muscular Dystrophy".

- ^ a b "Error 403".

- ^ a b Forrest, S.M.; Cross, G.S.; Flint, T.; Speer, A.; Robson, K.J.H.; Davies, K.E. (February 1988). "Further studies of gene deletions that cause Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophies". Genomics. 2 (2): 109–114. doi:10.1016/0888-7543(88)90091-2. PMID 3410474.

- ^ a b Becker Muscular Dystrophy~clinical at eMedicine

- ^ Darras, Basil T.; Urion, David K.; Ghosh, Partha S. (1993). "Dystrophinopathies". GeneReviews®. University of Washington, Seattle. PMID 20301298.

- ^ Tavallaee, Zachary; Hamby, Tyler; Marks, Warren (December 2022). "Myalgic Becker Muscular Dystrophy Due to an Exon 15 Point Mutation: Case Series and Literature Review". Journal of Clinical Neuromuscular Disease. 24 (2): 106–110. doi:10.1097/CND.0000000000000413. PMID 36409343. S2CID 253733072.

- ^ Mah, Jean K.; Korngut, Lawrence; Dykeman, Jonathan; Day, Lundy; Pringsheim, Tamara; Jette, Nathalie (June 2014). "A systematic review and meta-analysis on the epidemiology of Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophy". Neuromuscular Disorders. 24 (6): 482–491. doi:10.1016/j.nmd.2014.03.008. PMID 24780148. S2CID 20687867.

- ^ Grimm, Tiemo; Kress, Wolfram; Meng, Gerhard; Müller, Clemens R (December 2012). "Risk assessment and genetic counseling in families with Duchenne muscular dystrophy". Acta Myologica. 31 (3): 179–83. PMC 3631803. PMID 23620649.

- ^ a b "Becker muscular dystrophy | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program". Archived from the original on 2016-04-28. Retrieved 2016-04-19.

- ^ RESERVED, INSERM US14 -- ALL RIGHTS. "Orphanet: Becker muscular dystrophy". www.orpha.net. Retrieved 2016-04-19.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Dany, Antoine; Barbe, Coralie; Rapin, Amandine; Réveillère, Christian; Hardouin, Jean-Benoit; Morrone, Isabella; Wolak-Thierry, Aurore; Dramé, Moustapha; Calmus, Arnaud; Sacconi, Sabrina; Bassez, Guillaume; Tiffreau, Vincent; Richard, Isabelle; Gallais, Benjamin; Prigent, Hélène; Taiar, Redha; Jolly, Damien; Novella, Jean-Luc; Boyer, François Constant (4 July 2015). "Construction of a Quality of Life Questionnaire for slowly progressive neuromuscular disease". Quality of Life Research. 24 (11): 2615–2623. doi:10.1007/s11136-015-1013-8. PMID 26141500. S2CID 25834947.

- ^ a b Angelini, C; Marozzo, R; Pegoraro, V (September 2019). "Current and emerging therapies in Becker muscular dystrophy (BMD)". Acta Myologica: Myopathies and Cardiomyopathies. 38 (3): 172–179. PMC 6859412. PMID 31788661.

- ^ "Duchenne/Becker Treatment and Care | Muscular Dystrophy | NCBDDD | CDC". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2016-04-19.

- ^ "Dystrophinopathies Treatment & Management: Medical Care, Consultations, Activity". 2017-01-07.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Verhaert, David; Richards, Kathryn; Rafael-Fortney, Jill A.; Raman, Subha V. (January 2011). "Cardiac Involvement in Patients With Muscular Dystrophies". Circulation: Cardiovascular Imaging. 4 (1): 67–76. doi:10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.110.960740. PMC 3057042. PMID 21245364.

- ^ Reutenauer, J; Dorchies, O M; Patthey-Vuadens, O; Vuagniaux, G; Ruegg, U T (29 January 2009). "Investigation of Debio 025, a cyclophilin inhibitor, in the dystrophic mdx mouse, a model for Duchenne muscular dystrophy". British Journal of Pharmacology. 155 (4): 574–584. doi:10.1038/bjp.2008.285. PMC 2579666. PMID 18641676.

- ^ Bushby, Kate; Lochmüller, Hanns; Lynn, Stephen; Straub, Volker (November 2009). "Interventions for muscular dystrophy: molecular medicines entering the clinic". The Lancet. 374 (9704): 1849–1856. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61834-1. PMID 19944865. S2CID 41929569.

- ^ Delisa, Joel A; Gans, Bruce M; Walsh, Nicholas E (2005). Physical medicine and rehabilitation: Principles and practice. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 915–16. ISBN 978-0-7817-4130-9.

- ^ "Facts | Muscular Dystrophy | NCBDDD | CDC". 2018-04-10.

- ^ "Muscular Dystrophy Information Page: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS)". July 30, 2016. Archived from the original on 30 July 2016.

- ^ a b "Muscular Dystrophy: Hope Through Research". September 30, 2016. Archived from the original on 30 September 2016.

- ^ a b c "NINDS Muscular Dystrophy Information Page". NINDS. March 4, 2016. Archived from the original on 30 July 2016. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- ^ "Muscular Dystrophy: Hope Through Research". NINDS. March 4, 2016. Archived from the original on 30 September 2016. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- ^ Becker, P. E.; Kiener, F. (1955). "Eine neue x-chromosomale Muskeldystrophie" [A new x-linked muscular dystrophy]. Archiv für Psychiatrie und Nervenkrankheiten (in German). 193 (4): 427–448. doi:10.1007/BF00343141. PMID 13249581. S2CID 22284081.

- ^ Becker, P.E. (1957). "Neue Ergebnisse der Genetik der Muskeldystrophien" [New results of genetics of muscular dystrophy]. Human Heredity (in German). 7 (2): 303–310. doi:10.1159/000150994. PMID 13469170.

Further reading

- "Becker Muscular Dystrophy (for Parents)." Edited by Mena T. Scavina, KidsHealth, The Nemours Foundation, Mar. 2018, kidshealth.org/en/parents/becker-md.html.

- Gaudio, Daniela del; Yang, Yaping; Boggs, Barbara A.; Schmitt, Eric S.; Lee, Jennifer A.; Sahoo, Trilochan; Pham, Hoang T.; Wiszniewska, Joanna; Craig Chinault, A.; Beaudet, Arthur L.; Eng, Christine M. (September 2008). "Molecular diagnosis of Duchenne/Becker muscular dystrophy: enhanced detection of dystrophin gene rearrangements by oligonucleotide array-comparative genomic hybridization". Human Mutation. 29 (9): 1100–1107. doi:10.1002/humu.20841. PMID 18752307. S2CID 21437006.

- Li, Xihua; Zhao, Lei; Zhou, Shuizhen; Hu, Chaoping; Shi, Yiyun; Shi, Wei; Li, Hui; Liu, Fang; Wu, Bingbing; Wang, Yi (2015). "A comprehensive database of Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophy patients (0–18 years old) in East China". Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 10 (1): 5. doi:10.1186/s13023-014-0220-7. PMC 4323212. PMID 25612904.