Barwari

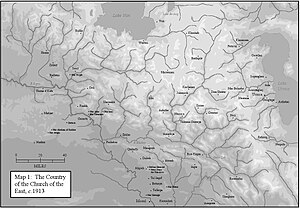

Barwari (Syriac: ܒܪܘܪ,[1] Kurdish: بهرواری, romanized: Berwarî)[2] is a region in Lower Tyari in the Hakkari mountains in northern Iraq and southeastern Turkey. The region is inhabited by Assyrians and Kurds, and was formerly also home to a number of Jews prior to their emigration to Israel in 1951.[3] It is divided between northern Barwari in Turkey, and southern Barwari in Iraq. The Assyrian people who inhabit this speak dialects of Suret, a modern form of the Aramaic language.

Etymology

The name of the region is derived from "berwar" ("slope [of a hill]" in Kurdish).[4]

History

The British archaeologist Austen Henry Layard visited Barwari Bala in 1846 and noted that some villages in the region were inhabited by both Assyrians and Kurds.[5] Assyrians of Barwari Bala were rayah (subjects) of the Kurdish emirate of lower Barwari,[6] whilst Assyrians in Barwari Shwa'uta were partly semi-independent and partly rayah.[7] In the 1840s, a series of massacres of Assyrians in Barwari Bala were perpetrated by Kurdish tribes under the leadership of Bedir Khan Beg, Mir of Bohtan, resulting in the death or expulsion of half of the population.[6] The region was estimated by American Presbyterian missionaries to contain 32 Assyrian villages, with 420 Nestorian families, in 1870.[8]

Amidst the Assyrian genocide in the First World War, in 1915, most Assyrian villages in Barwari Bala were destroyed and their inhabitants slaughtered by Turkish reservists and Kurdish tribesmen led by Rashid Bey, Mir of lower Barwari, whilst the survivors took refuge in the vicinity of Urmia and Salamas in Iran.[9] Assyrian villages in northern Barwari were similarly pillaged and their inhabitants massacred.[10] Until the genocide in 1915, northern Barwari was inhabited by approximately 9000 Assyrians, whilst there were c. 5000 Assyrians in southern Barwari.[11] Survivors were transferred under British protection from Iran to the refugee camp at Baqubah in Iraq in 1918, where they remained until most families attempted to return to their villages in 1920.[12]

As a consequence of the partition of the Ottoman Empire, most of Hakkari was allocated to Turkey, which prevented Assyrians from returning,[13] whilst Assyrians in southern Barwari in Iraq were permitted to return to their original villages.[12] The Assyrians of southern Barwari suffered major upheaval with the eruption of the First Iraqi–Kurdish War in 1961, forcing a sizeable number to flee and seek refuge in Iraqi towns until most returned at the war's conclusion in 1970, during which time a few Assyrian villages were seized and settled by Kurds.[12] In accordance with the 1975 Algiers Agreement between Iraq and Iran, the Iraqi government carried out border clearings in 1977-1978,[14] destroying a number of Assyrian and Kurdish villages, and displacing their population.[15]

Villages that had been spared in the late 1970s were destroyed by the Iraqi Army in the Al-Anfal campaign in 1987-1988, and all Assyrians in the region were moved to refugee camps, from which they moved to Iraqi towns or emigrated abroad to Europe, North America, or Australia.[9] In total, all 82 villages in the sub-district of Barwari Bala were destroyed in the campaign,[16] of which 35 villages were entirely inhabited by Assyrians.[14] Assyrians returned to rebuild their villages after the establishment of the Iraqi no-fly zones in 1991, however, the majority have remained in the diaspora.[9]

Geography

Iraq

Southern or lower Barwari corresponds to the part of the region now located within northern Iraq, and encompasses Barwari Bala and Barwari Žēr. Barwari Bala ("upper Barwari" in Kurdish) is a sub-district in Amadiya District within the Dohuk Governorate,[17] and is located alongside the Iraq–Turkey border.[4] The sub-region of Barwari Bala is separated from the Sapna valley to the south by the Matina mountains, and from the historical region of Lower Tyari in Hakkâri Province in Turkey by the Širani mountains to the north.[18] Its eastern border is defined by the Great Zab, beyond which lies Nerwa Rekan, and the Khabur serves as the western boundary of Barwari Bala.[4] Barwari Žēr ("lower Barwari" in Kurdish) is located further to the south of Barwari Bala.[4]

The following villages in Barwari Bala are currently inhabited by Assyrians:[19][20]

- Tarshīsh

- Jdīdā

- Beṯ Kolke[21]

- Tūṯā Shamāyā

- Māyā

- Derishke[22]

- Aïnā d'Nūne

- Hayyat

- Beṯ Shmiyāye

- Dūre

- Helwā

- Malakṯā

- Aqrī[23]

- Beṯ Balōkā

- Hayyis

- Mūsākān

- Merkaje

- Qasrka

- Baz

- Betanure

- Sardasht

- Cham Dostina

- Khwara[24]

- Kani Balavi

- Jelek

- Iden

- Chaqala

The following villages in Barwari Bala were formerly inhabited by Assyrians:

Turkey

The districts of Barwari Sevine,[nb 1] Barwari Shwa'uta,[nb 2] Barwari Qudshanes, and Bilidjnaye were located in southeastern Turkey,[4] and constituted northern or upper Barwari.[10][32]

The following villages in Barwari Sevine were formerly inhabited by Assyrians:[33]

The following villages in Barwari Qudshanes were formerly inhabited by Assyrians:[39]

- Qūdshānīs

- Beṯ Nānō

- Nerwā

- Tīrqōnīs

- Kīgar

- Sōrīnes

- Tarmel

- Beṯ Ḥājīj

- Peḥḥen

- Chāros

The following villages in Bilidjnaye were formerly inhabited by Assyrians:[40]

The following villages in Barwari Shwa'uta were formerly inhabited by Assyrians:[40]

References

Notes

Citations

- ^ "Bahra Magazine" (PDF). Bahra Magazine. 7 November 2010. Retrieved 23 April 2020.

- ^ Hamelink (2016), p. 351.

- ^ Mutzafi (2008), p. 8.

- ^ a b c d e Khan (2008), p. 1.

- ^ Aboona (2008), pp. 5–6.

- ^ a b Khan (2008), p. 3.

- ^ a b c Aboona (2008), p. 87.

- ^ Mooken (2003), pp. 61–62.

- ^ a b c Khan (2008), p. 2.

- ^ a b Yacoub (2016), p. 115.

- ^ Yonan (1996), pp. 27, 87.

- ^ a b c Khan (2008), pp. 2–3.

- ^ Travis (2006), p. 334.

- ^ a b Donabed (2015), p. 179.

- ^ Khan (2008), pp. 1–2.

- ^ Noory (2012), p. 108.

- ^ a b Donabed (2015), p. 112.

- ^ Khan 2008, p. 1; Aboona 2008, pp. 5–6.

- ^ "Christian Communities in the Kurdistan Region". Iraqi Kurdistan Christianity Project. 2012. Archived from the original on 24 November 2020. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- ^ Wilmshurst (2000), p. 150.

- ^ "Beqolke". Ishtar TV. 31 August 2011. Retrieved 4 September 2020.

- ^ "Derishke (Muslims and Christians)". Ishtar TV. 26 November 2012. Retrieved 4 September 2020.

- ^ "Iqri". Ishtar TV. 11 August 2011. Retrieved 4 September 2020.

- ^ "Khwara". Ishtar TV. 21 February 2013. Retrieved 4 September 2020.

- ^ a b Wilmshurst (2000), p. 149.

- ^ Donabed (2015), p. 298.

- ^ Donabed (2015), p. 292.

- ^ Donabed (2015), p. 293.

- ^ Donabed (2015), p. 300.

- ^ Donabed (2015), p. 302.

- ^ Aboona (2008), p. 294.

- ^ Yonan (1996), pp. 87–88.

- ^ Aboona 2008, p. 294; Wilmshurst 2000, p. 295.

- ^ "Tepeli". Index Anatolicus. Retrieved 10 October 2023.

- ^ "Kaymaklı". Index Anatolicus. Retrieved 10 October 2023.

- ^ "Çaltıkoru". Index Anatolicus. Retrieved 10 October 2023.

- ^ "Akbulut". Index Anatolicus. Retrieved 10 October 2023.

- ^ "Doğanca". Index Anatolicus. Retrieved 10 October 2023.

- ^ Wilmshurst 2000, p. 295; Aboona 2008, p. 293.

- ^ a b Aboona 2008, p. 294; Wilmshurst 2000, p. 294.

- ^ "Kapılı". Index Anatolicus. Retrieved 10 October 2023.

- ^ "Odabaşı". Index Anatolicus. Retrieved 10 October 2023.

- ^ "Kolbaşı". Index Anatolicus. Retrieved 10 October 2023.

- ^ "Yuvalı". Index Anatolicus. Retrieved 10 October 2023.

- ^ "Damlacık". Index Anatolicus. Retrieved 10 October 2023.

Bibliography

- Aboona, Hirmis (2008). Assyrians, Kurds, and Ottomans: Intercommunal Relations on the Periphery of the Ottoman Empire. Cambria Press. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- Donabed, Sargon George (2015). Reforging a Forgotten History: Iraq and the Assyrians in the Twentieth Century. Edinburgh University Press.

- Hamelink, Wendelmoet (2016). The Sung Home. Narrative, Morality, and the Kurdish Nation. Brill.

- Khan, Geoffrey (2008). The Neo-Aramaic Dialect of Barwar. Brill.

- Mooken, Aprem (2003). The History of the Assyrian Church of the East in the Twentieth Century. St. Ephrem's Ecumenical Research Institute. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- Travis, Hannibal (2006). ""Native Christians Massacred": The Ottoman Genocide of the Assyrians during World War I". Genocide Studies and Prevention. 1 (3): 327–372. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- Mutzafi, Hezy (2008). The Jewish Neo-Aramaic Dialect of Betanure (province of Dihok). Otto Harrassowitz Verlag.

- Noory, Alan M. (2012). Shopping for Identity: An Economic Explanation for the Post-2003 Violence in Iraq (PhD dissertation). University of Missouri–St. Louis. OCLC 794855377. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- Wilmshurst, David (2000). The Ecclesiastical Organisation of the Church of the East, 1318–1913. Peeters Publishers.

- Yacoub, Joseph (2016). Year of the Sword: The Assyrian Christian Genocide, A History. Translated by James Ferguson. Oxford University Press.

- Yonan, Gabriele (1996). Lest We Perish: A Forgotten Holocaust : the Extermination of the Christian Assyrians in Turkey and Persia (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2021. Retrieved 7 May 2020.