The Boat Race 1995

| 141st Boat Race | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Date | 1 April 1995 | ||

| Winner | Cambridge | ||

| Margin of victory | 4 lengths | ||

| Winning time | 18 minutes 4 seconds | ||

| Overall record (Cambridge–Oxford) | 72–68 | ||

| Other races | |||

| Reserve winner | Goldie | ||

| Women's winner | Cambridge | ||

| |||

The 141st Boat Race took place on 1 April 1995. Held annually, the Boat Race is a side-by-side rowing race between crews from the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge along the River Thames. Marko Banovic became the first rower from Croatia to participate in the event. Cambridge won by four lengths.

In the reserve race, Cambridge's Goldie defeated Oxford's Isis, while Cambridge won the Women's Boat Race.

Background

The Boat Race is a side-by-side rowing competition between the University of Oxford (sometimes referred to as the "Dark Blues")[1] and the University of Cambridge (sometimes referred to as the "Light Blues").[1] First held in 1829, the race takes place on the 4.2-mile (6.8 km) Championship Course on the River Thames in southwest London.[2] The rivalry is a major point of honour between the two universities and followed throughout the United Kingdom and broadcast worldwide.[3][4] Cambridge went into the race as reigning champions, having won the 1994 race by 6+1⁄2 lengths,[5] with Cambridge leading overall with 71 victories to Oxford's 68 (excluding the "dead heat" of 1877).[6] The race was sponsored by Beefeater Gin for the ninth consecutive year.[7]

The first Women's Boat Race took place in 1927, but did not become an annual fixture until the 1960s. Until 2014, the contest was conducted as part of the Henley Boat Races, but as of the 2015 race, it is held on the River Thames, on the same day as the men's main and reserve races.[8] The reserve race, contested between Oxford's Isis boat and Cambridge's Goldie boat has been held since 1965. It usually takes place on the Tideway, prior to the main Boat Race.[5]

Oxford saw former coach and Blue Dan Topolski return as director of coaching following his departure after the 1992 race.[9] Topolski, who rowed for the Dark Blues in the 1967 race, had coached Oxford to ten consecutive victories from 1976 to 1985.[10] He noted: "We know we are underdogs. We started with only one man from a previous Blues race and no internationals. Nothing but big hearts and lungs". Cambridge's boat club president Richard Phelps was upbeat: "We're buoyant, tails up, the boat's been going fast."[10] Cambridge were coached by Robin Williams who was reserved in his assessment, noting his crew needed to be "comfortable with the situation of rowing side-by-side."[11]

Crews

The official weigh-in took place at The Hurlingham Club five days before the race. The Oxford crew weighed on average 2.5 pounds (1.1 kg) more than their opponents.[12] Cambridge saw the return of four former Blues while Oxford's crew featured two.[12] The Oxford crew contained two native British rowers to Cambridge's five.[13] Cambridge's crew also featured the first rower from Croatia in the Boat Race, in Marko Banovic.[14] Oxford's cox, 19-year-old Abbie Chapman, became the ninth female cox in the history of the contest, and as a result of her diminutive stature, standing 4 ft 10 in (1.47 m) tall, her seat was raised to afford her the visibility required to steer.[12]

| Seat | Oxford |

Cambridge | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | College | Weight | Name | College | Weight | |

| Bow | Jonathan R W Kawaja | Mansfield | 13 st 9.5 lb | Roger D Taylor | Trinity Hall | 14 st 4 lb |

| 2 | Garth Rosengren | New College | 14 st 3 lb Richard C Phelps (P) | St Edmund's | 14 st 1 lb | |

| 3 | Boris Mavra | Jesus | 14 st 13 lb | Simon B Newton | Emmanuel | 14 st 10 lb |

| 4 | Laird St Reed | St Catherine's | 15 st 5 lb | Matthew H Parish | St Edmund's | 14 st 7 lb |

| 5 | Jeremiah B McLanahan (P) | Pembroke | 14 st 1.5 lb | Dirk Bangert | Fitzwilliam | 13 st 0 lb |

| 6 | Hugh S Corroon | Keble | 14 st 2 lb | Scott A Brownlee | St Edmund's | 14 st 8 lb |

| 7 | D Robert H Clegg | Keble | 14 st 6.5 lb | Marko Banovic | St Edmund's | 14 st 2 lb |

| Stroke | Jorn-Inge Thronsden | St Peter's | 14 st 0.5 lb | Miles P Barnett | Queens' | 13 st 7 lb |

| Cox | Abbie C Chapman | St Hilda's | 7 st 1 lb | Russell S Slatford | Hughes Hall | 7 st 1 lb |

| Source:[12] (P) – boat club president[10] | ||||||

Race

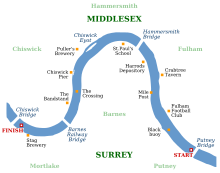

Cambridge won the toss and elected to start from the Surrey station.[15] In a stiff headwind,[14] Oxford took an early lead but as Cambridge's rhythm improved, they closed the gap and took the lead. Aggressive steering from Oxford's Chapman resulted in warnings from the umpire, yet by Craven Cottage, Cambridge held a lead of two-thirds of a length, and were a second ahead at the Mile Post.[13] A length ahead by Harrods Furniture Depository, a push at Hammersmith Bridge increased the lead to a length-and-a-half and allowed Cambridge a clear water advantage by Chiswick Eyot.[14] Although rating considerably lower than Oxford, Cambridge held their lead and passed the finishing post four lengths ahead, in a time of 18 minutes 4 seconds.[5][14]

In the reserve race, Cambridge's Goldie won by fourteen lengths over Isis, the largest margin of victory since the 1971 race, and Cambridge's eighth victory in nine years.[5] Cambridge won the 50th Women's Boat Race by 1+1⁄3 lengths in a time of 6 minutes and 2 seconds, their sixth victory in seven years.[5]

Reaction

Cambridge's Croatian international Banovic said "Matching them over the first two minutes and delaying our effort to Hammersmith was part of our plan."[15] His president, Phelps, confirmed "We knew they had four or five minutes in them ... we waited for them to crack."[15] Topolski reflected: "We had a great first seven minutes ... Cambridge are on a roll that has taken years to build up."[15] He continued: "You cannot expect our system to bear fruit in just a year".[13] The race was watched by around seven million viewers in the United Kingdom, the fifth most-viewed sports event of the year.[16]

References

- ^ a b "Dark Blues aim to punch above their weight". The Observer. 6 April 2003. Archived from the original on 11 September 2014. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- ^ Smith, Oliver (25 March 2014). "University Boat Race 2014: spectators' guide". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 1 July 2014. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- ^ "Former Winnipegger in winning Oxford–Cambridge Boat Race crew". CBC News. 6 April 2014. Archived from the original on 24 September 2014. Retrieved 9 July 2014.

- ^ "TV and radio". The Boat Race Company Limited. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 7 July 2014.

- ^ a b c d e "Boat Race – Results". The Boat Race Company Limited. Archived from the original on 12 July 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- ^ "Classic moments – the 1877 dead heat". The Boat Race Company Limited. Archived from the original on 26 October 2014. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- ^ "Professionalism arrives". The Boat Race Company Limited. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ^ "A brief history of the Women's Boat Race". The Boat Race Company Limited. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- ^ Miller, David (8 April 1996). "Story of Light Blue dominance set to run and run". The Times. No. 65548. p. 21.

- ^ a b c Miller, David (1 April 1995). "Topolski aims to weave his spell". The Times. No. 65230. p. 40.

- ^ Rosewell, Mike (1 April 1995). "Tide flows Light Blue way". The Times. No. 65230. p. 40.

- ^ a b c d Rosewell, Mike (28 March 1995). "Oxford bank on bulk to redress Boat Race balance". The Times. No. 62556. p. 38.

- ^ a b c Rosewell, Mike (3 April 1995). "Light Blue victors fly flag for British rowing". The Times. No. 62562. p. 27.

- ^ a b c d Williams, Richard (2 April 1995). "Light Blues victorious at a stroke". The Independent. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- ^ a b c d Miller, David (3 April 1995). "Oxford forced to endure pain without gain". The Times. No. 65232. p. 27.

- ^ Miller, David (6 April 1996). "Oxford dream needs Topolski for inspiration". The Times. No. 65547. p. 44.